Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania

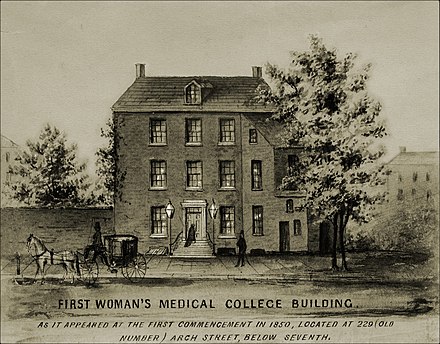

An 1850 illustration of the first building at Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia | |

Other name | WMCP |

|---|---|

Former name | Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, Medical College of Pennsylvania |

| Active | 1850–1970 (became co-ed Medical College of Pennsylvania) |

| Address | 229 Arch Street (until 1858) and then 627 Arch Street (after Philadelphia's street renumbering) , , , U.S. |

Founded in 1850 The Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) formally known as The Female Medical College of Pennsylvania was the first American medical college dedicated to teaching women medicine and allowing them to earn the Doctor of Medicine M.D. degree[1]

History

The Womans Medical College of Pennsylvania provided educational opportunities and medical training to some of the earliest women physicians, many of whom went on to break barriers of their own. Some of these pioneers, who had few rights or opportunities as women became among the first of their race or country to earn medical degrees: alumnae include the first Native American woman doctor and second African- American woman doctor as well as the first woman with Western medical degrees in India, Syria, Japan and Canada[2].

The associated Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia was founded in 1861. Upon deciding to admit men in 1970, the college was renamed the Medical College of Pennsylvania (MCP).

In 1930, the college opened its new campus in the East Falls section of Philadelphia, which combined teaching and the clinical care of a hospital in one overall facility. It was the first purpose-built hospital in the nation.

In 1993, the college and hospital merged with Hahnemann Medical School.

In 2003, the two colleges were absorbed by Drexel University College of Medicine.

R.C. Smedley's History of the Underground Railroad cites Bartholomew Fussell with proposing, in 1846, the idea for a college that would train female doctors. It was a tribute to his departed sister, who Bartholomew believed could have been a doctor if women had been given the opportunity at that time. Her daughter, Graceanna Lewis, was to become one of the first woman scientists in the United States. At a meeting at his house, The Pines, in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, Fussell invited five doctors to carry out his idea. The doctors invited were: Edwin Fussell (Bartholomew's nephew) M.D., Franklin Taylor, M.D., Ellwood Harvey, M.D., Sylvester Birdsall, M.D., and Dr. Ezra Michener. Graceanna also attended. Dr. Fussell would support the college, but had little to do with it after it started in 1850 in Philadelphia.[3]

Ellwood Harvey, who attended the 1846 meeting, but did not start teaching at the college until 1852, helped keep the school alive, along with Edwin Fussell. Dr. Harvey not only taught a full course load but took on a second load when another professor backed out.

Dr. Harvey also continued his medical practice. Among his patients were William Still and his family. Still, a renowned Philadelphia abolitionist, became a historian of the Underground Railroad after keeping extensive records of fugitive slaves aided in Philadelphia rescues.

Harvey was later sued for libel by Dr. Joseph S. Longshore, an instructor at the college who was forced out. Longshore started a rival women's medical college at the Penn Medical University. Using his previous connections from the Female Medical College, Longshore began to raise money for his own college.

The Feminist Movement during the early to mid 19th century generated support for the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania. The Society of Friends in Philadelphia, a large group of Quakers, were supportive of the women's rights movements and the development of the Female MCP.[4]

MCP was initially located in the rear of 229 Arch Street in Philadelphia; it was changed to 627 Arch Street when Philadelphia renumbered streets in 1858.[5] In July 1861, the board of corporators of the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania chose to rent rooms for the college from the Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia on North College Avenue.[6]

Admissions

Curriculum

Administration

The first dean of what was then known as the Female Medical College was Nathaniel R. Mosely, who served in the position from 1850 until 1856.[7] The second dean was also a man, Edwin B. Fussell, who held the position from 1856 to 1866.[8]

From then on, the Woman's College had a long history of female deans, lasting almost 100 years. The first woman to be a dean of this (or any) medical school was Ann Preston.[9] The following women were deans of the college in the years stated:

- 1866–1872, Ann Preston[10]

- 1872–1874, Emeline Horton Cleveland[11]

- 1874–1886, Rachel Bodley[12]

- 1886/1888–1917, Clara Marshall[13]

- 1917–1940, Martha Tracy[14] (Henry Jump served as interim dean during Tracy's sabbatical.)

- 1940/1943–1943/1946, Margaret Craighill

- 1946–1963, Marion Spencer Fay[15]

No woman was found to replace Marion Fay. After her, the position of dean was held by Glen R. Leymaster from 1964 to 1970,[16] at which time the institution became known as the Medical College of Pennsylvania.[17]

Issues in clinical training

The Female Medical College of Pennsylvania faced difficulties in providing clinical training for its students.[18] Almost all medical institutions were confronted with the demand for more clinical practice due to the rise of surgery, physical diagnosis, and clinical specialties.[19] During the 1880s, clinical instruction at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania relied mainly on the demonstration clinics.[18]

In 1887, Anna Broomall, professor of obstetrics for the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, established a maternity outpatient service in a poor area of South Philadelphia for the purpose of student education.[18] By 1895, many students cared for three or four women who were giving birth.[20]

East Falls campus and Drexel University

In the late 1920s, the college raised money to build a new campus. Designed by Ritter & Shay, the most successful of the Philadelphia

architecture firms in the 1920s, the East Falls Campus was the first purpose-built hospital in the nation. The design allowed both teaching and hospital care to take place in one facility, helping provide for more clinical care. Post-WWII housing shortages in the city were a catalyst for development of additions to the East Falls Campus, the first of which was the Ann Preston Building (designed by Thaddeus Longstreth), which provided housing and classrooms for student nurses.

Today, the building is known as the Falls Center. It is operated by Iron Stone Real Estate Partners as student housing, commercial space, and medical offices.[21]

In 1993, the Medical College of Pennsylvania merged with Hahnemann Medical College, retaining its Queen Lane campus. In 2003, the two medical colleges were absorbed as a part of Drexel University College of Medicine, creating new opportunities for the large student body for clinical practice in settings ranging from urban hospitals to small rural practices.

Notable alumni

Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States[2].

Rebecca Cole was the first black graduate of Women's Medical College to be awarded an MD in 1867. Followed by Caroline Still Anderson and Giorgianna E. Patterson Young who were the next black graduates awarded medical degree in 1878 [22]

In popular culture

In the TV series, "Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman[23]," fictional Dr. Michaela Quinn (Jane Seymour), graduates from this college.

See also

- List of defunct medical schools in the United States

- List of female scientists before the 20th century

- Women in medicine

References

- ^ "Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Remembering the Pioneering Women From One of Drexel's Legacy Medical Colleges". drexel.edu. March 27, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Smedley, Robert C. (1883). History of the Underground Railroad. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 268. OCLC 186383647.

- ^ Peitzman, Steven J. (2000). A new and untried course : Woman's Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850 – 1998. New Brunswick, NJ [u.a.]: Rutgers University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8135-2815-1.

- ^ Peitzman, Steven J. (2000). A new and untried course : Woman's Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850 – 1998. New Brunswick, NJ [u.a.]: Rutgers University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8135-2815-1.

- ^ Peitzman, Steven J. (2000). A new and untried course : Woman's Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850 – 1998. New Brunswick, NJ [u.a.]: Rutgers University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8135-2815-1.

- ^ "Female physicians and female medical college". Ohio Cultivator. No. VIII. 1852. p. 28. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Howard Atwood (1920). American Medical Biographies. Baltimore, MD: The Norman, Remington Company. pp. 418–419. ISBN 9781235663499. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Mandell, Melissa M. "Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania". The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ Fay, MS (July 1965). "Ann Preston: Dean of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1866–1872". Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 33: 43–8. PMID 14344617.

- ^ "Dr. Emeline Horton Cleveland". Changing the face of medicine. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ "Rachel L. Bodley papers 291". PACSCL Finding Aids. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ "Dr. Clara Marshall". Changing the face of medicine. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ Rogers, Fred B. (December 1964). "Martha Tracy (1876–1942): Exceptional Woman of Public Health". Archives of Environmental Health. 9 (6): 819–821. doi:10.1080/00039896.1964.10663931. PMID 14203108.

- ^ "Marion Spencer Fay Award". Institute for Women's Health and Leadership. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ "News and Comment". Archives of Environmental Health. 8 (4): 625–628. April 1964. doi:10.1080/00039896.1964.10663727.

- ^ Dixon, Mark (2011). The hidden history of Chester County : lost tales from the Delaware and Brandywine Valleys. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1609490737.

- ^ a b c Peitzman (2000), A New and Untried Course, p. 78

- ^ Edward Atwater, "'Making Fewer Mistakes': A History of Students and Patients," pp. 165–187, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 57, 1983

- ^ Peitzman (2000), A New and Untried Course, p. 79

- ^ Mastrull, Diane. "Falls Center is still evolving/ The historic location of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania is now becoming a medical and educational complex. The center continues to attract new tenants". Philly.com. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Female Medical College of Pennsylvania (Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania) · William Still: An African American Abolitionist · Temple University Libraries Exhibits Development". exhibits.temple.edu. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman (Drama, Family, Western), Jane Seymour, Joe Lando, Shawn Toovey, CBS, Sullivan Company, January 1, 1993, retrieved April 22, 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Further research

- Archives at Drexel University College of Medicine

- Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

- Dr. Ellwood Harvey, Underground Railroad Conductor on Facebook

40°00′43″N 75°11′03″W / 40.01190°N 75.18420°W / 40.01190; -75.18420