User:SpartaN/sandbox

| Roman Gaul Gallia (Latin) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||||||||

| 121 BC–c. 486 | |||||||||||

Province map of the Roman Empire, Gallic provinces highlighted | |||||||||||

| Capital | Lugdunum (de facto) later Trier (de jure) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||||

• Narbo Martius founded | 121 BC | ||||||||||

• Conquered by Julius Caesar | 58-50 BC | ||||||||||

• Augustan Division | c. 16-13 BC | ||||||||||

• Diocletian Division | c. 296 | ||||||||||

• End of Roman rule | c. 486 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

Roman Gaul (Latin: Gallia Romana) refers to Gaul under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. The expansion into Gaul proper begins with the annexation of Transalpine Gaul in 121 BC and finishes with the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC) of Julius Caesar. Parts of the region remain under semi-Roman rule until the collapse of Soissons following the Battle of Soissons in AD 486.

Geographically, Roman Gaul encompassed all of modern France and parts of Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Provincial divisions of Gaul evolved over time, going from 3 provinces in the time of Augustus (first century BC) to 17 after Diocletian (third century AD). Important cities include Narbonne (Narbo Martius), Lyon (Lugdunum), and Marseille (Massalia).

The defense of the Rhine was important to Gallo-Roman identity and servicing the legions stationed there was significant to the Gallic economy. Legions often participated in treasonous behavior.

All of Gaul was not conquered until Caesar's campaigns in the 50s BC. It would take a full generation until the imperial framework for provinces are setup with administrative centers in cities ruling over tribal states, assessed for taxation with the census, and grouped separately for their cults. Starting in the south, many colonies begin appearing in this period and then spread to the north. This system stood for 300 years with only slight adjustments, the most significant of which is the separation of military zones along the Rhine into Germania Superior and Germania Inferior.[1]

Geography

The provinces of Gaul had a combined area of roughly 234,455 square miles (607,240 km2), and includes lands currently part of France, Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Metropolitan France makes up the majority of Gaul's land area at 211,000 square miles (550,000 km2).[2][3]

Geographical divisions over time

Organization under the Republic

Before the reorganization under Augustus, Gaul had three geographical divisions, one of which was divided into multiple Roman provinces:

- Gallia Cisalpina or "Gaul this side of the Alps", covered most of present-day northern Italy. Its conquest was completed in 191 BC, but was not made a formal province until after the Social War (91–87 BC). By the end of the republic it was annexed into Italy itself.[4]

- Gallia Transalpina, or "Gaul across the Alps", was originally conquered and annexed in 121 BC in an attempt to solidify communications between Rome and the Iberian peninsula. It comprised most of what is now southern France, along the Mediterranean coast from the Pyrenees to the Alps. It was later renamed Gallia Narbonensis, after its capital city, Narbo Martius.[5]

- Gallia Comata (Gaul beyond the Transalpine province), encompassed the remainder of present-day France, Belgium, and western Germany, including Aquitania, Gallia Celtica and Belgica. The region had tributary status throughout the second and first centuries BC, but was still formally independent of Rome. It was annexed into the Empire as a result of Julius Caesar's victory in the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC).[6]

Reorganization under Augustus

After ca. 16—13 BC the Romans divided Gallia Comata into three provinces, the "Three Gauls":[7]

- Gallia Aquitania, corresponding to central and western France; Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes) and then from Limonum Pictonum (Poitiers)[8]

- Gallia Belgica, corresponding to northeastern France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and western Germany; capital at Reims, later Trier[9]

- Gallia Lugdunensis, corresponding to eastern and northern France; capital at Lugdunum (Lyon),[9] the de facto capital of the Three Gauls as a whole.[8]

The Three Gauls had been divided in ca. 16—13 BC into Lugdunensis, Aquitania, and Belgica. The term Gallia Comata was still in regular use until the time of Vespasian, when inscriptions begin to show the term Tres Galliae (lit. "Three Gauls") in reference to the new provinces Lugdunensis, Aquitania, and Belgica.[10]

Germania Inferior and Germania Superior were created from parts of Belgica under Domitian after the winter of AD 84/5 but before 90. They were detached from Gaul as part of Domitian's reorganization of the frontier with Germany.[11]

Reorganization under Diocletian

Following the Crisis of the Third Century, Diocletian reorganized the Roman provinces under the new system of tetrarchy. Gaul is placed into the new prefecture also called Gaul and divided into two dioceses:[12]

- Dioecesis Galliarum: Belgica I, Belgica II, and Maxima Sequanorum (from Belgica); Germania I (from Germania Superior), Germania II (from Germania Inferior); Alpes Poeninae et Graiae; Lugdunensis I, Lugdunensis II, and Lugdunensis III (from old Lugdunensis).

- Dioecesis Viennensis: Aquitania I, Aquitania II, Aquitania III Novempopulania (from Aquitania); Narbonensis I, Narbonensis II, and Viennensis (from Narbonensis); and Alpes Maritimae (from Narbonensis and Alpes Cottiae).

After Diocletian, Gallia was normally used to refer to the dioecesis Galliarum and the dioecesis Viennensis rather than the praetorian prefecture of Gaul which includes Britain, Spain, and Mauretania Tingitana as well. It does, however, include Germania Prima and Germania Secunda. The plural Galliae could sometimes also refer to the praetorian prefecture.[13]

Geology

Gaul had a number of mountain ranges: the Cevennes (Cevenna) stretching north-northeast from the Pyrenees; an extinct volcanic group in Auvergne (then Arverni) whose highest points are the Cantal, Mont Dor, and Puy-de-Dome; the Voges (Vosegus), running west of and parallel to the Rhine from Bale to Coblentz; the Jura Mountains, forming the boundary between the Helvetii and Sequani; and the portions of the Alpines that lie to the west and south of the Upper Rhine, whose streams are a source for the Rhine and the Rhône.[14]

It is also home to the Garonne, Loire, Meuse, Rhine, Rhône, Seine, Scheldt, and Somme basins (then under different names). The following were major rivers in Gaul:[15]

- the Garonne (Garumna) flows from the Pyrenees going northwest into the Bay of Biscay;

- the Loire (Liger) first flows northward, then westward into the Atlantic;

- the Meuse (Mora) flows northward from Pouilly-en-Bassigny into Belgium and then the Netherlands where it lets out in the North Sea;

- the Rhine (Rhenus) rises in the central Alps, and is enclosed by the Alpine ranges until it expands into Lacus Briganlinus v Venetus, the lake of Constance. Thence it flows westward till it reaches Basilia (Bale) until it reaches the Jura and the Voges where it turns abruptly to the north;

- the Rhône (Rhodanus) flows west from Geneva, disappears and flows underground for a quarter of a mile, and turns sharply to the south toward the Mediterranean; and

- the Seine (Sequana) rises in the table-land of the Plateau de Langres and, after its junction with Marne, encloses an islet called Lutetia Parisiorum at the heart of modern Paris.

Gulf of Pictons,[1] (Lacus Duorum Corvorum) which formed the boundary between the Gallo-Roman cities of Pictones to the north and Santones to the south.

Climate

Belgica's climate was cooler and wetter in the eighth to second centuries BC, followed by a period of relative warmth and dryness in the first century BC. The latter period saw the extensive coastal lagoons gradually dry up from the first Dunkirk transgression. This occurrence was attested to by Caesar (unaware of what he was witnessing) during his excursions there in the conquest of Gaul.[16]

The northeastern parts of Gaul are more of a continental climate because of its distance from the temperate influences of the Atlantic, but also doesn't see any decrease in annual rainfall. The marshes of eastern Belgica and dense forests form natural barriers to communication and travel between Gaul and Germania.[17] Parts of Gaul north of the Ardennes are part of the geological zone belong to the London basin, sharing it with parts of southern England. The London basin in Gaul includes regions from the plains of Hainaut and Flanders along with the chalk cliffs and flatlands to the west in the Boulonnais, Artois, and Picardie.[18]

Much of the country had soil suitable for argriculture. Northern Gaul wasn't as dry back then; the water-table was higher in Roman times because of greater precipitation. All of the Paris basin was covered with fertile 'limon', similar to loess, which was heavier than but more productive than the light soil of Champagne. Animal husbandry was likely more prominent in eastern Gaul, especially in Lorraine with it's heavy soil.[19]

History

A Roman presence in France can first be seen during the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage. Carthage loses the First Punic War, ceding Sardinia and Sicily to Rome. This causes Carthage to prioritize its colonies in Spain, making the south of France a critical stretch of land, because it connects Spain to Italy. In the Second Punic War the Carthaginian general Hannibal enters the Alps through Gaul in 189 BC with a large force including elephants to invade Italy, but loses after initial success. The Gauls and Massalia are paid for helping Rome in this conflict.[20]

Early Roman period

Also in 189 BC, praetor Lucius Baebius Dives was attacked in southern France on his way to Hispania Citerior by the Ligurians. He died in nearby Massalia. The attack against him marks the first major event involving the Romans in Gaul, and the beginning of conflict between the two peoples. In 181 BC, Gaius Matienus was dispatched to Massalia with ten warships to conduct anti-piracy operations on their request. Massaliot envoys again reach Rome in 154 BC for help agains the Ligurians. Quintus Opimius is sent to relieve the Greek cities in southern France and wins two victories, granting to Massalia the lands of the Oxybii and Deciates. Cicero stresses the importance of Massalia in Rome's victories against the Gauls.[21]

Massalia calls Rome for help again in 125 BC. The Saluvii, the Ligurians, and the Vocontii are defeated by two legions under Marcus Fulvius Flaccus. The year after, Rome sent an army under consul Gaius Sextius Calvinus. He founded the castellum Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence)in 122 BC. Once Spain was defeated (?), the strip connecting Spain to Italy was taken by Sextius and placed under the Massaliots, becoming Provincia Transalpina (later Gallia Narbonensis; "Narbonese Gaul") in 121 BC.[22] It was a strip of 1,400 to 2,200 meters along the Mediterranean coast, stretching to Lake Geneva. It's eastern border (with Italia) was the River Var. The consul Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus had a highway connecting Italy to Spain constructed in 118 BC, the Via Domitia. 118 BC also saw the establishment of a citizen colony in Narbo Martius (Narbonne, France). Gaul beyond the Narbonensis/Transalpina province was called Gallia Comata ("Long-haired Gaul").[5]

In Cicero's speech Pro Fonteio (ca. 70 BC) he describes Transalpine Gaul as being populated by uncontrolled savages surrounding the civilized Italian farmers.[23] The only Roman citizens present in the region were tax collectors, farmers, stock-raisers, and traders. They are described as being completely surrounded by enemies, except for their faithful ally Massalia.[24] Before Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul, there are only a few Roman settlements in the region: the forts Aquae Sextiae and Tolosa; three forums Forum Julii, Forum Voconti, and Forum Domitii; and a Pompeian foundation Lugdunum Covenarum. They are all positioned along the route connecting Italy to Spain.[24]

Gallic Wars

Julius Caesar becomes active in Transalpine Gaul in 58 BC and it is from there that he sees his means of attaining glory and the support of the Roman people he could not find in the Senatorial order which viewed him with contempt. It's position near Gallia Comata made it an ideal launching site for taking the rich lands to the north under the pretense of protecting Roman interests. The Helvetii, fleeing aggressive German tribes, are expected to begin a long journey across Gaul from east to west, and this is the pretext Caesar needs to enter Gaul, claiming the movements of such a tribe would threaten the security of Transalpine Gaul by agitating the other tribes in Gaul. He and his legate Titus Labienus block the Helvetii from crossing the Rhône into Gaul, they then pursue the Helvetii until they catch them crossing the Saône, where they quickly defeat them.[25]

Caesar makes his winter quarters in eastern Gaul which arouses the hostility of the Belgian tribes to the north. In response to their war preparations, Caesar raises two more legions and marches against them in early 57 BC with eight legions. Speed allowed him to break the unified Belgian force in a single skirmish after which he conquers their disunified states. Publius Crassus, son of the triumvir Crassus, was sent with a legion to convince the tribes along the English Channel and the Atlantic coast to submit to Rome and they did. Even Germanic tribes to the east of the Rhine sent Caesar hostages and promised loyalty to him.[26]

Caesar returns to Gaul in 56 BC to put down a revolt by the seafaring Veneti tribe and deal with a couple powerful tribes who crossed over from Germany. He claims they acted treacherously during negotiations and begins a slaughter, considered brutal even by Roman standards. In 55 BC he impresses the German tribes with a rapid campaign of raids across the Rhine enabled by speedy bridge building.[27]

In 53 BC Caesar again returns to put down a rebellion in northern Gaul which cost him an entire legion and was serious enough he had to recruit two more legions and borrow one from fellow triumvir Pompey. That winter the tribes plotted a coordinated revolt under Vercingetorix which began in 52 BC. Caesar surprised Vercingetorix by bringing in reinforcements from Transalpine Gaul through deep mountain snows. The response was scorched earth tactics and a guerrilla campaign from the Gauls. Caesar committs all ten of his legions and defeats Vercingetorix in the hilltop town Alesia after a difficult siege. Uxellodunum was the last holdout of the rebellion Caesar had to retake. He cut off the hands of all male prisoners taken from the city in retribution. Caesar was now firmly in control of Gaul.[28]

Late republican period

Gaul was pacified and Caesar was intent on keeping it that way. Careful not to upset the Gauls, the peace treaties he imposed were lenient and he levied few new taxes. Caesar was especially careful not to upset the Gauls since his position back at Rome was worsening. Crassus fell in battle in 53 BC and Pompey was shoring up his position with the Senate, who were turning against him.[29] Pompey did not intervene to protect Caesar when they demanded Caesar give up his command in Gaul, which he no longer needed because the war was over, and return to Rome as a private citizen which would mean certain political suicide.[30]

Caesar chose instead to fight rather than face political ruin in Rome and brought his ten legions with him from Gaul. The auxiliaries of his legions were mostly Gallic and Germanic tribesmen. One of his legions, the Legio V Alaudae, was comprised entirely of Gauls from Transalpine Gaul. They were given the franchise for their service.[31]

Massilia allied itself to Pompey in the civil war which led to its eventual defeat at the Siege of Massilia in 49 BC. It occupied a strategic position on the route connecting Italy to Spain, and a commanding position near the Rhône estuary, making it important for control over Transalpine Gaul as well.[32] The city's decision to side with Pompey was difficult for Caesar because of it's commanding position along the supply lines which supplied his legions in Hispania from Italia and from the heart of Gaul.[33] Gaul's role in Caesar's Civil War was important as a launching point, but most of the fighting happens elsewhere.

Territories were formerly divided between the Second Triumvirate in 43 BC (formalized on 27 November). Cisalpine Gaul and Gallia Comata went to Mark Antony while Lepidus took Gallia Narbonensis (along with Hispania and Africa).[34] After the Battle of Philippi a treaty is signed in December 42 BC, giving Gallia Narbonensis to Antony while Lepidus is given provinces in Africa.[35] In 40 BC the Treaty of Brundisium gives Antony the eastern provinces and Octavian the western provinces, including Gaul. Octavian had to pull troops out of the region for the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, which proved decisive for him. In 28 BC, troops are sent to pacify southwestern parts of Gual and northern Spain.[36]

Julio-Claudian rule

Octavian (now Augustus) visits Gaul himself in 27 BC and formally divides it into four provinces: the three provinces of Gallia Belgica, Gallia Lugdunensis and Gallia Aquitania, which weren't significantly different from Caesar's partition of Gaul; and the southernmost province, Gallia Narbonensis. Augustus had an army sent to defeat the Salassi who ruled the area connecting Italy to the Rhine (in the Great St Bernard Pass through what is now Switzerland). They were extracting tolls and harassing Roman merchants.[36]

Augustus made his general and friend Agrippa governor of Gaul. In 20 BC, improvements were made to the Roman road network. Rome increased its military presence on the Rhine and several forts were constructed there between 19 and 17 BC. Augustus thought that the future prosperity of the Empire depended on the expansion of its borders, and Germania had become the next target for imperial expansion.[37][38]

From 16 to 13 BC, Augustus was active in Gaul. In preparation for the coming campaigns, Augustus established a mint at Lugdunum[2](Lyon) in Gaul, to supply a means of coining money to pay the soldiers, organized a census for collecting taxes in Gaul, and coordinated the establishment of military bases on the west bank of the Rhine.[37] 12 BC saw an uprising in Gaul – a response to the Roman census and taxation policy set in place by Augustus.[39]

These moves were preliminary steps towards imperialist ambitions in Germany. There were a couple border incidents with Germanic tribes who crossed into Gaul in this time, and the Alps east of the Helveti were taken in a pincer maneuver by Tiberius and Nero Claudius Drusus in 15 BC. This secured Gaul for future expeditions from the Rhine without fear of counterattacks from the Swiss-Austrian parts of the Alps.[36] Drusus was then made governor of the Three Gauls in 13 BC, and his authority extended over the Rhine and the legions stationed there he'd use to launch invasions into Germany.[37]

The first Roman census in Gaul is completed in 12 BC, which sparked small scale rebellion in the province. In Lugdunum, the Sanctuary of the Three Gauls is built with and Drusus commemorates an Altar to Rome and Augustus where the city's two rivers meet. The altar lists the sixty Gallic tribes. These activities by Drusus mark a formal integration of the region into the Roman world.[40]

AD 19 - first amphitheater in Gaul (Amphitheatre of the Three Gauls)

Debtor's rebellion

Gauls experienced financial difficulties under the Julio-Claudians beginning with the per capita tribute imposed by Rome and expanded upon by harsh tax collectors and policies enabling debt trapping. Under Tiberius, taxes in Gaul were raised to cover the costs of Germanicus' campaigns in Germania. However, the taxes remained in place even after fighting in Germany was over.[41]

Julius Sacrovir of the Aedui and Florus[3] of the Treveri, Gallic nobility serving in the Roman military, refused to pay this tribute and led an unsuccessful rebellion of 40,000 Gauls in AD 21 which was quickly suppressed by commander of the Upper Rhine Silius with two legions.[42]

Tacitus lists the reasons for the revolt as: indebtedness, the vices of the Roman lifestyle, a desire for liberty, and the recent death of Germanicus (d. AD 19).[43] Alain Ferdière includes religious causes like the increasing persecution of Druidism and a recent prohibition on human sacrifices under Tiberius.[44]

AD 43 - invasion of Britain under Claudius

AD 48 - Claudius allows Gallic senators (includes Vindex)

AD 54 - Claudius abolishes Druidry completely.

Revolt of Vindex

In March 68 CE another uprising begins in Gaul, led by the Gallic governor (of what province remains uncertain) Gaius Julius Vindex against the emperor Nero. Like past Gallic revolts, excessive taxation is among the causes.[45] His revolt was notably Roman in motive compared to previous uprisings, although he did appeal to nationalist sentiment for support. His primary goal was to replace Nero with a more worthy princeps, who he perceived as having many vices such as: avarice, cruelty, madness, and wantonness.[46][47]

Fighting between Vienna and loyalist Lugdunum broke out, with Vindex laying siege to Lugdunum for refusal to back him. Plutarch estimates Vindex's force at 100,000 strong, an estimate likely too high says Królczyk.[48] Chieftains in support of him were Asiaticus, Flavus and Rufinus whose details are obscure. The tribes of the Rhine were against Vindex, as were the Treveri and Lingones.[49]

Vindex was actively spreading propaganda to promote his cause and sent out letters to neighboring provinces for support. In April he found it in the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, Galba who defects to his cause and is declared imperator by his legions in Spain. Coinage with various personifications of Gaul and Spain together appear in circulation, one variant featuring busts of three women as the Three Gauls.[50]

Nero dispatches Lucius Verginius Rufus to Gaul, who lays siege to Vesontio near Lugdunum. Vindex hears word of Rufus' siege and heads north to deal with the loyalist threat. The two clash in a pitched battle resulting in the suicide of Vindex and decimation of his force (20,000 rebels killed). Following the battle, Rufus is proclaimed emperor by his legions although he declines it for himself. The armies of the Upper Rhine are the last to denounce Nero in the wake of this uprising.[51]

Despite the loss of Vindex, Galba becomes emperor with the support of the western provinces and the Praetorian Guard's commander Nymphidius Sabinus. Nero kills himself in June.[52]

The Long Year

The situation changed in January 69. Galba proved unpopular at Rome and with the legions of the Rhine. On New Years' the legions of the Lower Rhine rebelled again, this time in favor of their governor, Vitellius. Political machinations by the governor of Lusitania, Otho, resulted in the assassination of Galba by the Praetorian Guard. Suetonius notes that Otho was probably aware of the uprising of Vitellius but did not expect opposition from him.[53]

Vitellius began his march south through Gaul, during which he won the support of soldiers from Gaul and Britain. His legions were under the command of Aulus Caecina Alienus and Fabius Valens. Skirmishes began in mid-March in southern Gaul and continued until mid-April. Despite being understrength, Otho met Vitellius in battle 22 miles from Cremona where Vitellius had just been reinforced. On 14 April, in what's called the First Battle of Bedriacum, Otho's armies were defeated with some 40,000 dead on both sides. Otho committed suicide two days later making Vitellius emperor (officially on 19 April).[54] Vitellius was still moving through Gaul when he received the news, stopping at Lugdunum to celebrate on or about 24 May.[55]

The Danubian legions who were on their way to join Otho instead defect to Vespasian, operating from the eastern provinces, and later participate in the Second Battle of Bedriacum in 24 or 25 October in which Vitellius' forces are defeated leading to the victory of Vespasian. During this time, Gaius Julius Civilis of the Batavi had attempted an attack on the border at Castra Vetera which failed. However, following the defeat of the Vitellians at Bedriacum the leadership of the legions in Germany changed and many Gallic tribes defected to Civilis' Imperium Galliarum ("Gallic Empire").[56]

The Imperium Galliarum ("Gallic Empire") of Civilis possibly had their capital at Noviomagus. Joining the Batavi were the Treveri under Julius Classicus and Julius Tutor and the Lingones under Julius Sabinus. There were also two legions at Novaesium (Neuss) that were made to swear loyalty to the new Gallic Empire after the assassination of their leader Dillius Vocula.[56]

The initial response to Civilis was weak and fraught with setbacks. In early 70 forces were sent under Quintus Petillius Cerialis and Annius Gallus, alongside the emperor's youngest son Domitian. Cerialis and Domitian established themselves at Trier, after which they defeated Civilis at Rigodulum. The rebels were defeated at Castra Vetera and Civilis was forced to surrender in late 70.[57]

In a writing dating circa AD 70, Pliny the Elder describes Narbonese Gaul as "Italia verius quam provincia", the province par excellence. In the 140 years from Cicero the province had been civilized by Roman standards if Pliny is to be believed.[23] By his time, Gaul had become well regarded for its wine.[58]

Middle Roman period

(from Domitian article) "Once Emperor, Domitian immediately sought to attain his long delayed military glory. As early as 82, or possibly 83, he went to Gaul, ostensibly to conduct a census, and suddenly ordered an attack on the Chatti.[59] For this purpose, a new legion was founded, Legio I Minervia, which constructed some 75 kilometres (46 mi) of roads through Chattan territory to uncover the enemy's hiding places.[60]

Although little information survives of the battles fought, enough early victories were apparently achieved for Domitian to be back in Rome by the end of 83, where he celebrated an elaborate triumph and conferred upon himself the title of Germanicus.[61] Domitian's supposed victory was much scorned by ancient authors, who described the campaign as "uncalled for",[62] and a "mock triumph".[63] The evidence lends some credence to these claims, as the Chatti would later play a significant role during the revolt of Saturninus in 89."[64]

89: Revolt of Saturninus, governor of Germania Superior

177: Christian martyrs of Lyon

178-208: episcopate of Irenaeus of Lyon

186: uprisings of the brigands of Maternus

197: clodius albinus (usurper) killed by Septimius Severus in Lyon

253: invasion of Gaul by Franks and Alamanni

Crisis of the Third Century

In the Crisis of the Third Century around 260, Postumus established a short-lived Gallic Empire, which included the Iberian Peninsula and Britannia, in addition to Gaul itself. Germanic tribes, the Franks and the Alamanni, invaded Gaul at this time. The Gallic Empire ended with Emperor Aurelian's victory at Châlons in 274.

285-6: revolt of the Bagaudes

In 286/7 Carausius commander of the Classis Britannica, the fleet of the English Channel, declared himself Emperor of Britain and northern Gaul.[65] His forces comprised his fleet, the three legions stationed in Britain and also a legion he had seized in Gaul, a number of foreign auxiliary units, a levy of Gaulish merchant ships, and barbarian mercenaries attracted by the prospect of booty.[66] In 293 emperor Constantius Chlorus isolated Carausius by besieging the port of Gesoriacum (Boulogne-sur-Mer) and invaded Batavia in the Rhine delta, held by his Frankish allies, and reclaimed Gaul.

Late Roman period

(in AD 297) After the end of the Crisis of the Third Century, Diocletian divides the Roman Empire into a tetrarchy comprised of four new praetorian prefectures, that of Gaul being ruled from Trier by Constantius Chlorus. Gaul was subdivided further into diocesis, those in Gaul proper being made of the dioceses Gaul with 8 provinces and Vienne with 5 (later 7). The two dioceses of Gaul later become merged between AD 418 and 425.

The Severans had split up the provinces into smaller pieces to prevent a concentration of military forces to hopefully weaken potential usurpers. By the time Diocletian became emperor there were about fifty provinces, thirty percent more than under Marcus Aurelius. Diocletian then "sliced up the provinces into many pieces". This was less to do with protecting himself from usurpers, as the military governors of 30,000+ men had long since gone, and was instead about taxation and administration. Each of these new gallic provinces were now to be governed by equestrians who now could administer, deal out justice, and levy taxes. The bureaucracy exploded (though still small by modern standards), and as such these provinces were now grouped into larger units called dioceses, the Gauls ("Galliae"). In charge of the diocese was a vicarius (the vicarii were subordinates to the praetorian prefect).[67]

"The empire of the west was divided into two prefectures, that of Gaul and that of Italy. The prefecture of Gaul comprised three diocesses - Gaul, Spain, and Britain. At the head of the prefecture was a praetorian-prefect; at the head of each diocess a vice-prefect. The praetorian-prefect of Gaul resided at Trier. Gaul was divided into seventeen provinces, the affairs of each of which were administered by a governor of its own, under the general orders of the prefect. Of these provinces, six were governed by consulares (Viennensis, Lugdunensis 1; Germania Superior, Germania Inferior, Belgica 1 and 2), the other eleven by presidents (Alpes Maritimae, Alpes Penninae, Sequanensis 1; Aquitanica 1 and 2; Novempopulonia, Narbonensis 1 and 2; Lugdunensis 2 and 3 Lugdunensis Senonensis)."[68]

A migration of Celts from Britain appeared in the 4th century in Armorica led by the legendary king Conan Meriadoc.[citation needed] They spoke the now extinct British language, which evolved into the Breton, Cornish, and Welsh languages.[citation needed]

314: Council of Arles by Constantine I, first synod held in Gaul

355: invasions of Franks and Alamanni, who settle between Rhine and Moselle rivers

370-97: Martin of Tours, bishop

395: Death of Ausonius, Gallo-Roman poet

31 Dec 406-7: invasion of Gaul by Vandals, Burgundians, Suevi, Alamanni

418: installation of Visigoths in Aquitaine II

The Goths who had sacked Rome in 410 established a capital in Toulouse and in 418 succeeded in being accepted by Honorius as foederati and rulers of the Aquitanian province in exchange for their support against the Vandals.[69]

435-7: Great Revolt of the Bagaudes

Hun invasion

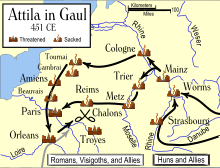

The Roman Empire had difficulty responding to all the barbarian raids, and Flavius Aëtius had to use these tribes against each other in order to maintain some Roman control. He first used the Huns against the Burgundians, and these mercenaries destroyed Worms, killed king Gunther, and pushed the Burgundians westward. The Burgundians were resettled by Aëtius near Lugdunum in 443. The Huns, united by Attila, became a greater threat, and Aëtius used the Visigoths against the Huns. The conflict climaxed in 451 at the Battle of Châlons, in which the Romans and Goths defeated Attila.

Gaul becomes a center for oratory in the late empire. Romano-Gallic performance stretches for a century in the Panegyrici Latini, a collection of twelve speeches made beginning with that of Pliny the Younger in 100 up until that of Claudius Mamertinus to Julian at Constantinople in 362. All of them but Pliny's were by Gallic orators; of those eleven panegyrics, eight were given in Gaul; of which seven were in Trier and one was at Autun in Lugdunensis Prima. One of these was Pacatus Drepanius, a student of the rhetorical school in Burdigala. Gaul had some of the best rhetorical schools in the west. There was an auditorium in Trier, since it's establishment as a tetrachic capital for Gaul, for those who wished to have the emperor's attention. Gaul was important enough by this time that senators had to travel out to the frontier zone, as the squeamishly metropolitan Symmachus had in 368-370, to pay homage to the emperor. Symmachus delivered golden tributes to Valentinaian I and his son Gratian on behalf of the Roman senate.[70]

After the fall of Rome

The Roman administration finally collapsed as remaining Roman troops withdrew southeast to protect Italy. Between 455 and 476 the Visigoths, the Burgundians, and the Franks assumed control in Gaul. However, certain aspects of the ancient Celtic culture continued after the fall of Roman administration and the Domain of Soissons, a remnant of the Empire, survived from 457 to 486.

481: Frankish king Clovis succeeds Childeric

In 486 the Franks defeated the last Roman authority in Gaul at the Battle of Soissons. Almost immediately afterwards, most of Gaul came under the rule of the Merovingians, the first kings of a proto-France.

In 507, the Visigoths were pushed out of most of Gaul by the Frankish king Clovis I at the Battle of Vouillé.[71] They were able to retain Narbonensis and Provence after the timely arrival of an Ostrogoth detachment sent by Theodoric the Great.

Certain Gallo-Roman aristocratic families continued to exert power in episcopal cities (such as the Mauronitus family in Marseilles and Bishop Gregory of Tours). The appearance of Germanic given and family names becomes noticeable in Gallia/Francia from the middle of the 7th century on, most notably in powerful families, indicating that the centre of gravity had definitely shifted.

The Gallo-Roman (or Vulgar Latin) dialect of the late Roman period evolved into the dialects of the Oïl languages and Old French in the north, and into Occitan in the south.

The name Gallia and its equivalents continued in use, at least in writing, until the end of the Merovingian period in the 750s. Slowly, during the ensuing Carolingian period (751-987), the expression Francia, then Francia occidentalis spread to describe the political reality of the kingdom of the Franks (regnum francorum).

Demographics

Gaul's population grows under Roman rule, peaking in the fourth century. Estimates have been made of the population in Roman Gaul based on assumptions regarding how many villas there are per kilometer and the percentage of farmers in the rural population. Anthony King estimates a rural population of 8 to 15 million.[72] Edith Wightman suggests an increase in density per km2 of the countryside from 11-14 persons per km2 in pre-Roman times to at least 15 per km2 by the second century.[73] Gaul was more agrarian than Italy but not as agrarian as Roman Britain. Only 10-15% of Romano-Gauls were not solely dependent on agricultural activities.[74][75]

The population of Gaul is higher than that of successive states in the region until the Middle Ages. The decline begins in the late Roman period as attested by the shrinkage of farmed lands, although it is uncertain what exactly the population becomes due to the frequent exchange of territory and chaos of the period.[73]

Cities and towns

Urban centers occur more frequently in southern and eastern Gaul, those areas closer to the Mediterranean and the garrisons along the Rhine. Lugdunum formed the central hub for commerce, from which most goods would be moved south to Arelate (now Arles, France) for further distribution across the sea. The concentration of cities to the east can be explained by their proximity to the Roman garrisons in Germany. The city-forts of Germany were closely integrated into the Gallic economy as the soldiers stationed there were reliant on nearby agricultural yields. German legions eagerly bought up Gallic luxury goods such as wine.[76]

There were approximately 100 civitas capitals and 400 other urban centers across the four Gauls. Woolf estimates an urban population range of 1 to 2 million.[77] Anthony King's urban estimate is within this range at 1,230,000 (including the 50,000 soldiers on the Rhine).[74]

Largest Urban Centers (second century low estimate) in Gaul

Wilson 2011, pp. 188–189 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Pop. | ||||||||

Lugdunum  Narbo Martius |

1 | Lugdunum | 25,000 |  Massilia  Burdigala | |||||

| 2 | Narbo Martius | 20,000 | |||||||

| 3 | Massilia | 15,000 | |||||||

| 4 | Burdigala | 15,000 | |||||||

| 5 | Nemausus | 12,000 | |||||||

| 6 | Arelate | 10,000 | |||||||

| 7 | Arausio | 10,000 | |||||||

| 8 | Forum Julii | 10,000 | |||||||

| 9 | Lutetia Parisiorum | 8,000 | |||||||

| 10 | Vienna | 8,000 | |||||||

Culture

I am going to need to read this again and begin the other article because it's a lot to get into, but marking the page here. [78] In the five centuries between Caesar's conquest and the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Gaulish language and cultural identity underwent a syncretism with the Roman culture of the new governing class, and evolved into a hybrid Gallo-Roman culture that eventually permeated all levels of society.[citation needed] Gauls continued writing some inscriptions in the Gaulish language, but switched from the Greek alphabet to the Latin alphabet during the Roman period. Current historical research suggests that Roman Gaul was "Roman" only in certain (albeit major) social contexts, the prominence of which in material culture has hindered a better historical understanding of the permanence of many Celtic elements.[citation needed] The Roman influence was most apparent in the areas of civic religion and administration. The Druidic religion was suppressed by Emperor Claudius I, and in later centuries Christianity was introduced. The prohibition of Druids and the syncretic nature of the Roman religion led to disappearance of the Celtic religion. It remains to this day poorly understood: current knowledge of the Celtic religion is based on archeology and via literary sources from several isolated areas such as Ireland and Wales.

Surviving Celtic influences also infiltrated back into the Roman Imperial culture in the 3rd century. For example, the Gaulish tunic—which gave Emperor Caracalla his surname—had not been replaced by Roman fashion. Similarly, certain Gaulish artisan techniques, such as the barrel (more durable than the Roman amphora) and chain mail were adopted by the Romans.

The Celtic heritage also continued in the spoken language (see History of French). Gaulish spelling and pronunciation of Latin are apparent in several 5th century poets and transcribers of popular farces.[79] The last pockets of Gaulish speakers appear to have lingered until the 6th or 7th century.[citation needed] Gaulish was held to be attested by a quote from Gregory of Tours written in the second half of the 6th century,[80] which describes how a shrine "called 'Vasso Galatae' in the Gallic tongue" was destroyed and burnt to the ground.[81] Throughout the Roman rule over Gaul, although considerable Romanization in terms of material culture occurred, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and continued to be spoken, coexisting with Latin.[80]

Germanic placenames were first attested in border areas settled by Germanic colonizers (with Roman approval). In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Franks settled in northern France and Belgium, the Alemanni in Alsace and Switzerland, and the Burgundians in Savoie.

Theaters and amphitheaters weren't just for cities. Many were placed far from urban centers to allow social functions for the rural peasants and plebs of Gaul. This was likely intended to act as a substitute for the social and religious gatherings traditionally allotted to Druids.[82] 25 of the 77 known amphitheaters (as of 2010) in Gaul are found at sites not identified as cities.[83]

Religion

An extensive survey published in 1993 by Isabelle Fauduet found that there were 653 temples across Gaul, 269 were built in settlements and the rest on open land. Those found in settlements are usually of the Classical Vitruvian style seen in Italian cities.[85] Of those whose date of construction are certain: 98 were built in the first century CE, 38 in the second century, 8 in the third century, and none were built in the fourth century.[86] Of those whose date of abandonment are certain: 15 were abandoned in the first century, 34 in the second, 57 in the third, and 120 in the fourth or later.[87] Mithraeum (underground temples for Mithras) begin appearing in the second century. Of the Fauduet sample, there are 11 Mithraea in the four Gauls.[88]

Primary sources from the Roman period aren't fully reliable on the subject of native Gallic religion as they tend to focus on the bizarre elements like human sacrifices and Druids while often leaving out the more recognizable elements. It is also not entirely clear which native gods their Roman counterparts correctly correspond to. For example, Caesar gives the name of the Roman Dispater for the deity Gauls considered themselves descendant from.[89]

Existing deities were as accepted as Roman ones provided they were worshipped in the correct manner. The rites being performed had to conform to Roman norms, or else it was superstitio. The community one was from was a contributing factor to what was considered acceptable. Public cults and priesthoods from coloniae or municipia were expected to be organized along Roman lines whereas those from peregrine communities had more freedom to deviate.[90]

Augustus established an altar that was in the middle of the federal sanctuary in Lugdunum, the Ara trium Galliarum, designed to serve the Three Gauls that had been divided in ca. 16—13 BC into Lugdunensis, Aquitania, and Belgica. It was the center of the imperial cult in the Three Gauls featuring Augustus and Roma.[10] It had its own priests who performed sacrificial rites and held games for the public.[91]

Christianity is attested in Gaul beginning in the mid second century. It first appears in Vienne and then in Lugdunum. There was probably a Christian presence in Massalia first, from where the religion was first brought into the Rhone valley, and then works its way up the Rhone. The leader of the Lugdunum community, Pothinus, becomes a martyr during the persecution by Marcus Aurelius in AD 166/167.[92] Although there were enough martyrs to survive the persecution under his reign, the community in Gaul was still pretty small and consisted primarily of easterners.[93]

Sports

Gladiatorial combat was quickly adopted by Gallic cities as part of Gaul's romanization. The gallus (meaning a person from Gaul) type of gladiator seen in Rome was not likely accepted in Gaul as the reason it's named after Gauls is a reminder of their defeat. There is a type of gladiator native to Gaul, however, the heavily armored crupellarius. Some were recruited by rebel leader Sacrovir in the early first century, but did not fare well.[94]

Last chariot race was in the ??? century. Don't forget to include.

Economy

In the early days of the province, most of the economic activity was based in the south. Over time, however, more goods began to be produced domestically in central Gaul for ease of availability in servicing the nearby troops stationed along the Rhine. This lessened the issues with long distance bulk trade. Over time, the production centers began to move further north and east into Gaul, and the province becomes a major producer of goods like samian ware and wine in the area surrounding Trier.[95]

Trade

Military supply routes led to the development of a trade hub centered at Lugdunum, with the Rhône, Saône, Moselle and Rhine valleys as trade lanes. Lugdunum occupied the ideal location at the confluence of the Rhône and Saône rivers. There lies many epigraphic attestations to the vibrant merchant community which formed in the city, many of which were foreigners from places as distant as Syria. The city exported goods like glassware and pottery from it's riverfront workshop areas, cloaks from the city center, or wood from the surrounding area. Lugdunum had a cosmopolitan feel when compared to the other towns in Gaul.[96]

Other towns played a role in the trading hub: Arles near the mouth of the Rhône, moved goods from the Mediterranean onto river-craft; Chalon-sur-Saône moved goods up the Saône into the Moselle Valley; Metz and Trier, then Cologne and Mainz on the Rhine. All of which would facilitate trade with the "barbarians" beyond the Roman frontier into Germania Libera.[97]

Trans-Mediterranean trade along the southern coast of Gaul where the Rhône estuary links Hispania to Italy sees it's trade peak in the late 1st century BC and early 1st century AD, which can be measured by the amount of shipwrecks during the period. This is due to increased production from other provinces such as Hispania itself.[98]

Mining

There were many sources of metals in the province: south-western Gaul had gold and silver; the islands of the Cassiterides (Cornwall and the Isles of Sicily) had tin; Brittany had tin and copper (making it a valuable source of raw materials in the production of bronze) in addition to lead, iron, and silver ores; the area around Limoges had gold; the southern part of Massif Central around Montagne Noire had iron, lead, and silver as did the foothills of the Pyrenees.[99]

Limoges becomes an industrial mining center by the Roman period alongside it's three vici in it's vacinity: Praetorium (modern Saint-Goussaud) and Carovicus (modern Château-Chervix) had gold, Blotomagus (modern Blond) had tin.[99]

Iron production was more valuable in the region than precious metals. It was lucrative enough there was a procurator ferriarium galliarum ("procurator of Gallic iron-mines") based in Lugdunum, to oversee the iron mining operations as part of a state monopoly.[100] In the early first century AD Gaul became the major producer of weapons for the army of the Rhine, with major production occurring in the north and south until the military bases begin establishing their own weapon factories. Major centers include: Strasbourg, Macon, Autun, Soissons, Reims, Amiens, and Trier.[101]

The white marble from the quarries at Saint-Béat was considered high quality and can be found across the province. Most quarries only serve their local area.[102] Regions with more economic success had more quarry activity, particulary in the south-west of Gaul and the Massif Central. Poorer parts of the province like to the north-west saw less quarry activity despite the availability of good stone. By the late Empire even large quarries were beginning to fall into disuse. Towards the end of the Empire, when building walls for protection became a priority, towns began reusing stone blocks from existing structures to build them.[103]

Agriculture

Gaul's agricultural development was different in the north and south. In the north a "continental" system prevails whereas in the south, particularly in Narbonensis, a Mediterranean agrarian system thrives. Agricultural diversity was the norm although monoculture of certain crops did occur such as grapes to mass produce wine in Narbonensis.[104]

As in other parts of the Roman Empire, wheat and barley were the majority of Gaul's crop share. There appears to have been a shift towards rye in the 4th century as attested by archaeobotanical findings from villages in northern and southern Gaul. Rye is more resilient to the cold than other wheats, but we see the trend to the south near Amiens, where it replaces spelt. Some of the shift towards rye might be explained by the Late Antique Little Ice Age, but post-Roman Gaul under the Franks were devoted growers of traditional wheat and barley.[105]

(need to extract/find heather/expound on) "By 350 AD the climate had steadied and a half century of moderate warming suffused the northwestern provinces. But the Empire had been seriously shaken, says Heather. Agricultural output, population numbers, and local economies began to contract during the fourth century, first in Gallia Belgica and Germania Inforior, while agricultural declines emerged later in the southerly provinces. The early northern contractions, suggests Heather, were influenced by the disproportionate regional impost of Rome's increased military-funding taxes on farmers, exacerbated by more frequent barbarian incursions along that northeast border. Even so, the broad north-before-south geographic sequence of provincial decline also fits with what one might expect as the Mediterranean climate retracted southward."[106]

Pottery

The earlier styles of Roman pottery made in Gaul were Arretine, modeled on the Italian production from Arezzo during the mid-first century BC. This style was soon replaced by red-gloss samian ware favored by the military. Samian ware asserts itself as the controlling brand in Gaul and most other provinces by the end of the first century BC.[107] It is likely the potters working in Gaul's samian industry were free men, although most of them were not Roman citizens based on the lack of a tria nomina seen in records.[108]

The samian market begins to decline in the late second century AD and only worsens in the third century as trade becomes difficult due to the conflicts in the Empire making long distance trade more demanding. The quality of the product deteriorates and demand goes down. It is no longer in demand as competing products, such as coarse-ware, begins to take it's place in households. By the end of the third century moulded decorated ware (such as samian) ceases production altogether.[109]

Law and government

From the time of Caesar until Augustus, the Three Gauls were usually under the combined governorship of one governor as an extension of Transalpine Gaul. The Empire's grasp wasn't as strong as it could be in many of the local civitas, a problem Augustus looked to remedy.[110] After the reorganization of the provinces under Augustus each of the Gauls received it's own governor. Previously the governor would be a proconsul, but under the new system it would be a legate appointed by the emperor.[111] Administrative centers were setup in cities to rule over the tribal states, tax them, and run their cults.[112]

Like the legates, the procurators were incorporated into the provincial system, but there were never more than two procurators to cover the Three Gauls. The fiscal policies of Lugdunensis and Aquitania were both supervised from Lugdunum, likewise those of Belgica and Germania Inferior/Germania Superior were supervised in Augusta Treverorum.[113]

Taxation

The tributes extracted from Gaul, a sensitive tax collected by the procurators, was the primary means of taxation in the province by the Roman Empire. The tribute was twofold: the tributum soli ("ground-tribute") which was a tax on agricultural yield; and the tributum capitis ("head-tribute") which was a levy on wealth. The latter was only paid by non-citizen freedmen, the peregrini.[113] The tribute tax was resented by many Gauls as it was a reminder of their lot as a conquered people, whereas some Romans might remind them it went towards their protection from external attacks.[113]

The evaluation of the tributum, which all Gallic civitates were liable to pay, was dependent on the results of the census. There was often trouble extolling the census without incident. In the early Empire there would always be a member of the ruling house in the Three Gauls while it was conducted: Augustus in 27 BC, Drusus in 12 BC, and Germanicus in AD 14. Later a legati censitores of consular rank would become the norm (either one per province, or divided in the same manner as the procurators to the the Three Gauls and Germanies seen above).[114]

There's a gradual rise in strength and powers of equestrians in Gaul over time. By the early third century equestrians take the place of traditionally praetorian governors. Imperial legati appear in the region until the mid third century, and senators could still be granted extraordinary powers to inspect Gallic finances for Rome. Equestrians were trusted to collect the money, just not to evaluate the civitates over which they governed. The census in each province was supposed to be conducted once every fifteen years, but in practice was about once in every twenty-five. The results were tabulated into the archives in Lugdunum and Augusta Treverorum.[115]

Passive taxes existed too. One unique to Gaul was the Quadragesima Galliarum, a customs-duty tax of 2.5% at land frontiers, sea frontiers, and certain ports imposed on all incoming and outgoing goods in those lands. It was a means of raising revenue rather than protection funds. Other indirect taxes included: the Centesima venalis ("One per cent sales tax"); the Vicesima libertalis ("Five per cent tax on the freeing of slaves"); and the Vicesima hereditatium ("Five per cent estate duty"), which was situational and only affected Roman citizens.[100] The bureaucracy surrounding the Quadragesima Galliarum continued to grow in size and complexity, with its inspectors (praepositi stationum) scattered across the country, headquartered in Lugdunum.[116]

See also

- Asterix, French comic set in 50 BC Gaul

- Roman Britain's continental trade

Notes

References

- ^ Woolf 1997, p. 345

- ^ Clinton 1851, p. 424

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 8

- ^ Lovano 2014, pp. 372–4

- ^ a b Nelson 2017, pp. 14–15

- ^ Lovano 2014, pp. 378–80

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 93

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2014, p. 96

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2014, p. 95

- ^ a b Fishwick 2002, pp. 9–10

- ^ Southern 2013, p. 90

- ^ Talbert 2014, p. 202

- ^ Szidat 2015, p. 120

- ^ Hughes 2020, p. 11

- ^ Hughes 2020, pp. 11–12

- ^ Wightman 1985, pp. 4–5

- ^ Wightman 1985, p. 2

- ^ Wightman 1985, pp. 2–3

- ^ Wightman 1985, p. 4

- ^ Nelson 2017, p. 12

- ^ Nelson 2017, p. 13

- ^ Nelson 2017, p. 14

- ^ a b Bowman, Lintott & Champlin 1996, p. 172

- ^ a b Pellegrino 2020, p. 58

- ^ Ward, Heichelheim & Yeo 2016, p. 203

- ^ Ward, Heichelheim & Yeo 2016, p. 204

- ^ Ward, Heichelheim & Yeo 2016, pp. 205–206

- ^ Ward, Heichelheim & Yeo 2016, p. 206

- ^ Matyszak 2006, p. 62

- ^ Goldsworthy 2013, p. 5

- ^ Goldsworthy 2013, p. 6

- ^ Westall 2017, p. 143

- ^ Westall 2017, p. 144

- ^ Davies & Swain 2010, p. 223

- ^ Davies & Swain 2010, p. 228

- ^ a b c King 1990, p. 56

- ^ a b c Wells 2003, p. 77

- ^ Abdale 2016, p. 73

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 155

- ^ Cornwell 2016, p. 63

- ^ Wightman 1985, p. 64

- ^ Hogain 2003, p. 178

- ^ Lavan 2016, p. 30

- ^ Ferdière 2005, p. 174

- ^ Królczyk 2018, p. 859

- ^ Philostratus, Life of Apollonius 5.10

- ^ Królczyk 2018, p. 860

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Galba 4.3 (Królczyk 2018, p. 863)

- ^ Królczyk 2018, p. 863

- ^ Królczyk 2018, p. 865

- ^ Królczyk 2018, pp. 866–8

- ^ Królczyk 2018, pp. 868–9

- ^ Vagi 2000, pp. 189–90

- ^ Vagi 2000, pp. 190–91

- ^ Vagi 2000, p. 194

- ^ a b Vagi 2000, pp. 200–01

- ^ Vagi 2000, p. 201

- ^ Jashemski2017, pp. 134–135

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 28

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 130

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 129

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 6

- ^ Tacitus, Agricola 39

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 131

- ^ Panegyrici Latini, 8:6; Aurelius Victor, Book of Caesars 39:20-21; Eutropius, Abridgement of Roman History 21; Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans 7:25.2-4

- ^ Panegyrici Latini 8:12

- ^ Goldsworthy 2009, pp. 164–165

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_History_of_Civilization_from_the_Fal/HU5GAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=sequanensis&pg=PA35&printsec=frontcover

- ^ O'Callaghan, Joseph. "Spain: The Visigothic Kingdom". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Vessey 2010, p. 272

- ^ Bennett, Matthew (2004). "Goths". In Holmes, Richard; Singleton, Charles; Jones, Spencer (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford University Press. p. 367. ISBN 9780191727467

- ^ King 1990, p. 107

- ^ a b Wightman 1985, p. 121

- ^ a b King 1990, p. 108

- ^ Woolf 2000, p. 137

- ^ Jashemski2017, pp. 134–135

- ^ Woolf 2000, p. 138

- ^ Woolf 1997, p. 346

- ^ Histoire de France, ed. Les Belles lettres, Paris.

- ^ a b Laurence Hélix. Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise.

- ^ Hist. Franc., book I, 32 Veniens vero Arvernos, delubrum illud, quod Gallica lingua Vasso Galatæ vocant, incendit, diruit, atque subvertit. And coming to Clermont [to the Arverni] he set on fire, overthrew and destroyed that shrine which they call Vasso Galatæ in the Gallic tongue.

- ^ Grimal 1983, p. 66

- ^ Futrell 2010, p. 66

- ^ Ashton, Kasey. "The Celts Themselves." University of North Carolina. Accessed 5 November 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Raja & Rieger 2021, p. 274

- ^ Walsh 2018, p. 51

- ^ Goodman 2011, p. 167

- ^ Goodman 2011, p. 166

- ^ Woolf 2000, pp. 212–213

- ^ Woolf 2000, p. 214-215

- ^ Woolf 2000, p. 216

- ^ Behr 2006, p. 369

- ^ Behr 2006, p. 371

- ^ Dunkle 2013, p. 118

- ^ King 1990, pp. 116–117

- ^ King 1990, p. 115

- ^ King 1990, pp. 115–116

- ^ King 1990, p. 117

- ^ a b King 1990, p. 120

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2014, p. 100

- ^ King 1990, pp. 121–122

- ^ King 1990, p. 123

- ^ King 1990, pp. 124–125

- ^ Ferdière 2020, p. 447

- ^ Squatriti 2019, pp. 343–344

- ^ McMichael, Woodward & Muir 2017, pp. 144–145

- ^ King 1990, p. 126

- ^ King 1990, p. 131

- ^ King 1990, p. 130

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 93

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 96

- ^ Woolf 1997, p. 345

- ^ a b c Drinkwater 2014, p. 98

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 99

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, pp. 99–100

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 103

Bibliography

- Abdale, Jason R. (2016), Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 9781473860858

- Alston, Richard (1998), Aspects of Roman History AD 14–117, Routledge, ISBN 0-203-20095-0

- Behr, John (2006), "Gaul", in Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M.; Bowie, K. Scott (eds.), Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 1, Origins to Constantine, pp. 366–379

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes (1989), "The Geography of Power", B.A.R. International Series (477), ISBN 0860546144

- Bowman, Alan K.; Lintott, Andrew; Champlin, Edward, eds. (1996), The Cambridge Ancient History X: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.—A.D. 69, vol. 10

- Clinton, Henry Fynes (1851), An Epitome of the Civil and Literary Chronology of Greece: From the Earliest Accounts to the Death of Augustus

- Cornwell, Hannah (2016), "Alpine Reactions to Roman power", Official Power and Local Elites in the Roman Provinces, ISBN 9781317086147

- Davies, Mark Everson; Swain, Hillary (2010), Aspects of Roman History 82 BC - AD 14, ISBN 9781135151607

- Drinkwater, John (2014), Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 BC-AD 260, ISBN 9781317750741

- Dunkle, Robert (2013), Gladiators, ISBN 9781317905219

- Ferdière, Alain (2005), Les Gaules: provinces des Gaules et Germanies, provinces alpines IIe siècle BC-Ve siècle AD (in French), ISBN 9782200263690

- Ferdière, Alain (2020), "Agriculture in Roman Gaul", in Hollander, David B. (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Agriculture, ISBN 9781118970942

- Fishwick, Duncan (2002), The Imperial Cult in the Latin West: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, vol. III, ISBN 9780521789820

- Futrell, Alison (2010), Blood in the Arena, ISBN 9780292792401

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2013), Caesar's Civil War, ISBN 9781135881818

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009), How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower, ISBN 9780300155600

- Goodman, Penelope J. (2011), The Archaeology of the Late Antique "pagans", ISBN 9789004192379

- Gordon, Richard; Raja, Rubina; Rieger, Anna-Katharina (2021), "Economy and Religion", Religion in the Roman Empire, ISBN 9783170292253

- Grimal, Pierre (1983), Roman Cities

- Hogain, Daithi O (2003), the Celts, ISBN 9780851159232

- Hughes, William (2020), An Atlas of Classical Geography, ISBN 9783846047552

- Jashemski, Wilhemina F., ed. (2017), "Produce Gardens", Gardens of the Roman Empire, ISBN 9781108327039

- Jones, Brian W. (1992), The Emperor Domitian, ISBN 9780415101950

- King, Anthony (1990), Roman Gaul and Germany, ISBN 9780520069893

- Królczyk, Krzysztof (2018), "Rebellion of Caius Iulius Vindex Against Emperor Nero", Вестник СПбГУ. История, vol. 63, pp. 858–871

- Lavan, Myles (2016), "Writing Revolt in the Early Roman Empire", in Schoenaers, Dirk; Firnhaber-Baker, Justine (eds.), The Routledge History Handbook of Medieval Revolt, ISBN 9781134878871

- Lovano, Michael (2014), All Things Julius Caesar: An Encyclopedia of Caesar's World and Legacy, ISBN 9781440804212

- Maddison, Angus (2007), Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic history, ISBN 9780199227211

- Matyszak, Philip (2006), The Sons of Caesar, ISBN 9780500251287

- McMichael, Anthony; Woodward, Alistair; Muir, Cameron, eds. (2017), Climate Change and the Health of Nations Famines, Fevers, and the Fate of Populations, ISBN 9780190262969

- Nelson, Michael (2017), The French Riviera: A History, ISBN 9781785898334

- Pellegrino, Frida (2020), The Urbanization of the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire: A Juridical and Functional Approach to Town Life in Roman Gaul, Germania Inferior, and Britain, ISBN 9781789697759

- de Planhol, Xavier; Claval, Paul (1994), An Historical Geography of France, ISBN 9780521322089

- Southern, Pat (2013), Domitian, ISBN 9781317798446

- Squatriti, Paolo (2019), "Rye's Rise and Rome's Fall: Agriculture and Climate in Europe during Late Antiquity", in Izdebski, Adam; Mulryan, Michael (eds.), Environmnet and Society in the Long Late Antiquity, ISBN 9789004392083

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Szidat, Joachim (2015), "Gaul and the Roman Emperors in the Fourth Century", in Wienand, Johannes (ed.), Contested Monarchy, ISBN 9780199768998

- Talbert, Richard J. A. (2014), Ancient Perspectives, ISBN 9780226789408

- Vagi, David L. (2000), Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, ISBN 1579583164

- Walsh, David (2018), The Cult of the Mithras in Late Antiquity, ISBN 9789004383067

- Ward, Allen M.; Heichelheim, Fritz M.; Yeo, Cedric A. (2016), A History of the Roman People, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781315511207

- Vessey, Mark (2010), "Reinventing history: Jerome's Chronicle and the writing of the post-Roman west", in Watts, Edward J.; McGill, Scott; Sogno, Cristiana (eds.), From the Tetrarchs to the Theodosians: Later Roman History and Culture, 284–450 CE, ISBN 9781139489690

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wells, Peter S. (2003), The Battle That Stopped Rome, Norton, ISBN 9780393326437

- Westall, Richard (2017), Caesar's Civil War: Historical Reality and Fabrication, ISBN 9789004356153

- Wightman, Edith Mary (1985), Gallia Belgica, ISBN 9780520052970

- Wilson, Andrew (2011), Settlement, Urbanization, and Population, ISBN 9780199602353

- Woolf, Greg (1997), "Culture Contact and Colonialism", Beyond Romans and Natives, vol. 28, pp. 339–350

- Woolf, Greg (2000), Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul, ISBN 9780521789820

External links

- Romans in Gaul : A Webliography - A Teacher Workshop held at Temple University, November 3, 2001. Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden-Sydney College, Virginia