User:Morell21/sandbox

{{Multiple issues|POV = October 2011|essay-like = October 2011| {{too few opinions|date=October 2011}} }}

The Racial Achievement Gap in the United States refers to the educational disparities between minority students and Caucasian students. This disparity manifests itself in a variety of ways: African-American and Hispanic students are more likely to receive lower grades, score lower on standardized tests, drop out of high school, and are less likely to enter and complete college.[1] Asian-Americans generally perform similarly to Caucasian students and are therefore usually not studied in conjunction with Hispanics and African-Americans. The evidence, antecedents, implications and successes of the achievement gap are discussed below.

Evidence of the Racial Achievement Gaps

Over the past 45 years, students in the United States have made notable gains in academic achievement. However, the racial achievement gap remains because not all groups of students are advancing at the same rates. Evidence of the racial achievement gap has been manifested through early schooling test scores, standardized test scores, high school dropout rates, college acceptance and retention rates, as well as through longitudinal trends. While efforts to close the racial achievement gap have increased over the years with varying success, studies have shown that disparities still exist between achievement levels of minorities compared to Caucasian counterparts.

Early Schooling Years

Kindergarten Through Fifth Grade

The racial achievement gap has been found to exist before students enter kindergarten for their first year of schooling.[2] At the start of kindergarten, Hispanic and black students have math and reading scores substantially lower than those of white students. While both Hispanics and blacks scores have significantly lower test scores than their white counterparts, Hispanic and black have scores that are roughly equal to each other. Specifically, the average Hispanic and black students begin kindergarten with math scores three quarters of a standard deviation lower than those of white students and with reading scores a half standard deviation lower than those of white students. Six years later, Hispanic-white gaps narrow by roughly a third, whereas black-white gaps widen by about a third. More specifically, the Hispanic-white gap is a half standard deviation in math, and three-eighths in reading at the end of fifth grade. The trends in the Hispanic-white gaps are especially interesting because of the rapid narrowing that occurs between kindergarten and first grade. Specifically, the estimated math gap declines from 0.77 to 0.56 standard deviations, and the estimated reading gap from 0.52 to 0.29 in the roughly 18 months between the fall of kindergarten and the spring of first grade. In the four years from the spring of first grade through the spring of fifth grade, the Hispanic-white gaps narrow slightly to 0.50 standard deviations in math and widening slightly to 0.38 deviations in reading.[3]

Third Through Eighth Grade

Analysis of data from the North Carolina public school students in grades 3 to 8 has found gaps between four different racial groups: whites, Asians, Hispanics, and blacks.[4] Essentially, while the black-white gaps are substantial, both Hispanic and Asian students tend to gain on whites as they progress in school. The white-black achievement gap in math scores is about half a standard deviation, and the white-black achievement gap in reading is a little less than half a standard deviation. By fifth grade, Hispanic and white students have roughly the same math and reading scores. By eighth grade, scores for Hispanic students in North Carolina surpassed those of observationally equivalent whites by roughly a tenth of a standard deviation. Asian students surpass whites on math and reading tests in all years except third and fourth grade reading.[5]

Secondary School

Starting in the eight grade, white students have an intitial advantage in reading achievement over black and Hispanic students but not Asian students.[6] Specifically, black students score 5.49 points lower than white students and Hispanic students score 4.83 points lower than white students on reading tests. These differences in initial status are compounded by differences in reading gains made during high school. Specifically, between ninth and tenth grades, white students gain slightly more than black students and Hispanic students, but white students gain less than Asian students. Between tenth and twelfth grades, white students gain at a slightly faster rate than black students, but white students gain at a slower rate than Hispanic students and Asian students.[7]

In eighth grade, white students also have an initial advantage over black and Hispanic students in math tests.[8] However, Asian students have an initial 2.71 point advantage over white students and keep pace with white students throughout high school. Between eighth and tenth grade, black students and Hispanic students make slower gains in math than white students, and black students fall farthest behind. Asian students gain 2.71 points more than white students between eight and tenth grade. Some of these differences in gains persist later in high school. For example, between tenth and twelfth grades, white students gain more than black students, and Asian students gain more than white students. There are no significant differences in math gains between white students and Hispanic students. By the end of high school, gaps between groups increase slightly. Specifically, the initial 9-point advantage of white students over black students increases by about a point, and the initial advantage of Asian students over white students also increases by about a point. Essentially, by the end of high school, Asian students are beginning to learn intermediate-level math concepts, whereas black and Hispanic students are far behind, learning fractions and decimals, which are math concepts that the white and Asian students learned in the eighth grade. Black and Hispanic students end twelfth grade with scores 11 and 7 points behind those of white students, while the male-female difference in math scores is only around 2 points.[9]

Standardized Test Scores

The racial group differences across admissions tests, such as the SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, MCAT, LSAT, Advanced Placement Program examinations and other measures of educational achievement, have been fairly consistent. Since the 1960s, the population of students taking these assessments has become increasingly diverse. Consequently, the examination of ethnic score differences have been more rigorous.[10] Specifically, the largest gaps exist between white and African American students. On average, they score about .82 to 1.18 standard deviations lower than white students in composite test scores.[11] Following closely behind is the gap between white and Hispanic students. Asian American students performance were comparable to those of White students except Asian American students performed one quarter standard deviation unit lower on the SAT verbal section, and about one half a standard deviation unit higher in the GRE Quantitative test.[10]

The National Assessment of Educational Progress reports the national Black-White gap and the Hispanic-White Gap in math and reading assessments, measured at the 4th and 8th grade level. The trends show both gaps widen in mathematics as students grow older, but tend to stay the same in reading. Furthermore, the NAEP measures the widening and narrowing of achievement gaps on a state level. From 2007-2009, the achievement gaps for the majority of states stayed the same, although more fluctuations were seen at the 8th grade level than the 4th grade level.[12][13]

The Black-White Gap demonstrates:[12]

- In mathematics, a 26 point difference at the 4th grade level and a 31 point difference at the 8th grade level.

- In reading, a 27 point difference at the 4th grade level and a 26 point difference at the 8th grade level.

The Hispanic White Gap demonstrates:[13]

- In mathematics, a 21 point difference at the 4th grade level and a 26 point difference at the 8th grade level.

- In reading, there is a 25 point difference at the 4th grade level and a 24 point difference at the 8th grade level (NAEP, 2011).

The National Educational Longitudinal Survey (NELS, 1988) demonstrates similar findings in their evaluation of assessments administered to 12th graders in reading and math.[14]

Mathematics

Results of the mathematics achievement test:

Caucasian-African American Gap

Caucasian-Hispanic gap

Reading

Results of the reading achievement test:

Caucasian-African American Gap

Caucasian-Hispanic Gap

HIgh School Dropout Rates

According to the US Department of Education, event dropout rate is the percentage of high school students who dropped out of high school between the beginning of one school year and the beginning of the next school year.[15] Five out of every 100 students enrolled in high school in October 2000 left school before October 2001 without successfully completing a high school program. The percentage of students who were event dropouts decreased from 1972 through 1987. However, despite some year-to-year fluctuations, the percentage of students dropping out of school each year has stayed relatively the same since 1987. Data from the October 2001 Current Population Survey (CPS) show that black and Hispanic students were more likely to have dropped out of high school between October 2000 and October 2001 than were white or Asians/Pacific Islander students. During this period, 6.3% of black and 8.8% of Hispanic high school students dropped out compared to 4.1% of white and 2.3% of Asian/Pacific Islander high school students.[16]

According to the US Department of Education, status dropout rates measure the percentage of individuals who are not enrolled in high school and who lack a high school credential, independent of when they dropped out.[17] Status rates are higher than event rates because they include all dropouts in this age range, regardless of when they last attended school or whether or not they ever entered the US education system. In October 2001, about 3.8 million 16- through 24-year-olds were not enrolled in a high school program and had not completed high school. These individuals accounted for 10.7% of the 35.2 million 16- through 24-year-olds in the United States in 2001. In 1972, the white status dropout rate was 40% and the black status dropout rate was 49%. Because the black rate declined more steeply than the white rate, there has been a narrowing of the gap between the dropout rates for blacks and whites. However, this narrowing occurred in the 1980s, and the gap between whites and blacks has remained fairly constant since 1990. The percentage of Hispanics who were status dropouts has remained higher than that of blacks and whites in every year since 1970. Even though Hispanics represented approximately the same percentage of the young adult population as did blacks, Hispanics were disproportionately represented among status dropouts in 2001. Also in 2001, the status dropout rate for Asians/Pacific Islanders ages 16-24 was lower than for any other 16- through 24-year-olds. Specifically, the status rate for Asians/Pacific Islanders was 3.6%, compared with 27.0% for Hispanics, 10.9% for blacks, and 7.3% for whites.[18]

High School Completion Rates

Status completion rates measure the percentage of a given population that has a high school credential, regardless of when the credential was earned.[19] In 2001, 86.5% of 18- through 24-year-olds not enrolled in elementary or secondary school had completed high school. Status completion rates increased from 82.8% in 1972 to 85.6% in 1990. Since 1991, the rate has shown no consistent trend and has fluctuated between 84.8% and 86.5%. High school status completion rates for white and black young adults increased between the early 1970s and 1990 but has remained relatively the same since 1990. Specifically, status completion rates for white students increased from 86.0% in 1972 to 89.6% in 1990. Since 1990, white completion rates have remained in the range of 89.4–91.8%. In 2001, 91.0% of white and 85.6% of black 18- through 24-year-olds had completed high school. The percentage of black students completing high school rose from 72.1% in 1972 to 85.6% in 2001. The gap between black and white completion rates narrowed between 1972 and 2001. In 2001, 65.7% of all Hispanic 18- through 24-year- olds completed high school. This percentage compares to 91.0% of whites, 85.6% of blacks, and 96.1% of Asians/Pacific Islanders. Essentially, in 2001, whites and Asians/Pacific Islanders were more likely than their black and Hispanic peers to have completed high school. Also, whites completed high school at a higher rate than both blacks and Hispanic students. Black students completed high school at a higher rate than Hispanics.[20]

The four-year completion rate is the percentage of 9th-grade students who left school over a subsequent 4-year period while also completing a high school credential.[21] Data for the 4-year completion rate calculations are taken from the Common Core of Data (CCD). The 4-year completion rate calculation is dependent on the availability of dropout estimates over a 4-year span, and current counts of completers. Because dropout rate information was missing for many states during the 4-year period considered by the US Department of Education, 4- year completion rate estimates for the 2000-01 school year are only available for 39 states. Since data were not available from all states, an overall national rate could not be calculated. However, among reporting states, the high school 4-year completion rates for public school students ranged from a high of 90.1% in North Dakota to a low of 65.0% in Louisiana.[22]

SAT Scores

Racial and ethnic variations in SAT scores follow a similar pattern to other racial achievement gaps. In 1990, the average SAT was 491 for whites, 528 for Asians, 385 for blacks, and 429 for Mexican Americans.[23] 34% of Asians compared with 20% of whites, 3% of blacks, 7% of Mexican Americans, and 9% of Native Americans scored above a 600 on the SAT math section.[24] On the SAT verbal section in 1990, whites scored an average of 442, compared with 410 for Asians, 352 for blacks, 380 for Mexican Americans, and 388 for Native Americans. 8% of whites, 10% of Asians, 2% of blacks, 3% of Mexican Americans, and 3% of Native Americans scored above 600 on the SAT verbal section in 1990.[25]

College Enrollment and Graduation Rates

The US Department in Education demonstrates performance of different ethnic groups in colleges and universities. Specifically, they found that about 72% of Caucasian students who have completed high school enrolled in college the same year, compared to 44% for Black students, and 50% for Hispanic students.[26] Furthermore, trends in undergraduate and graduate enrollment have shown increases in all ethnicity groups, but the largest gap still exists for Black student enrollment. Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islanders student enrollment have experienced the most growth since 1976.[27] The 6-year national college graduation rate is 59% for Caucasian students, 51% for Hispanic students, 46% for Black females, and 35% for Black males.[28] Furthermore, even at prestigious institutions, the graduation rate of white students is higher than that of black student.[29]

Long-Term Trends

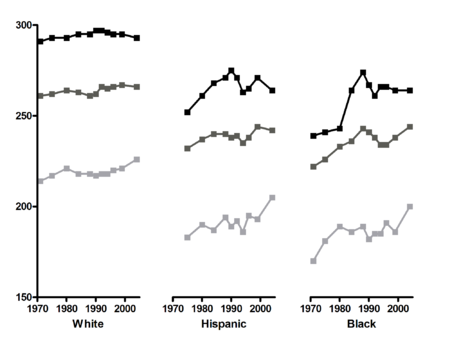

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) has been testing seventeen year olds since 1971. From 1971 to 1996, the black-white reading gap shrank by almost one half and the math gap by almost one third.[30] Specifically, blacks scored an average of 239 points, and whites scored an average of 291 points on the NAEP reading tests in 1971. In 1990, blacks scored an average of 267, and whites scored an average of 297 points. On NAEP math tests in 1973, blacks scored an average of 270, and whites scored 310. In 1990, black average score was 289 and whites scored an average of 310 points. For Hispanics, the average NAEP math score for seventeen year olds in 1973 was 277 and 310 for whites. In 1990, the average score among Hispanics was 284 compared with 310 for whites.[31]

Because of small population size in the 1970s, similar trend data are not available for Asian Americans.Data from the 1990 NAEP Mathematics Assessment Tests show that among twelfth graders, Asians scored an average of 315 points compared with 301 points for whites, 270 for blacks, 278 for Hispanics, and 290 for Native Americans.[32] Racial and ethnic differentiation is most apparent at the highest achievement levels. Specifically, 13% of Asians performed at level of 350 points or higher, 6% of whites, less than 1% of blacks, and 1% of Hispanics did so.[33]

The NAEP has since collected and analyzed data through 2008. Overall, the White-Hispanic and the White-Black gap for NAEP scores have significantly decreased since the 1970s.[34] The Black-White Gap demonstrates:[34]

- In mathematics, the gap for 17 year olds was narrowed by 14 points from 1973 to 2008.

- In reading, the gap for 17 year olds was narrowed by 24 points from 1971 to 2008.

The Hispanic-White Gap demonstrates:[34]

- In mathematics, the gap for 17 year olds was narrowed by 12 points from 1973 to 2008.

- In reading, the gap for 17 year olds was narrowed by 15 points from 1975 to 2008.

Furthermore, subgroups showed predominant gains in 4th grade at all achievement levels. In terms of achieving proficiency, gaps between subgroups in most states have narrowed across grade levels, yet had widened in 23% of instances. The progress made in elementary and middle schools was greater than that in high schools, which demonstrates the importance of early childhood education. Greater gains were seen in lower-performing subgroups rather than in higher-performing subgroups. Similarly, greater gains were seen in Latino and African American subgroups than for low-income and Native American subgroups.[35]

- Reading- ages 9 (light gray), 13 (dark gray), and 17 (black).

Origin of the Racial Achievement Gap

The achievement gap between low-income minority students and middle-income Caucasian students has been a popular research topic among sociologists since the publication of the report, "Equality of Educational Opportunity" (more widely known as the Coleman Report). This report was commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education in 1966 to investigate whether the performance of African-American students was caused by their attending schools of a lesser quality than white students. The report suggested that both in-school factors and home/community factors impact the academic achievement of students and contribute to the achievement gap that exists between races.[36]

Family factors

Children can differ in their readiness to learn before they enter school.[36] According to sociologist Annette Lareau, differences in parenting styles can impact a child’s future achievement. In her book Unequal Childhoods, she argues that there are two main types of parenting: concerted cultivation and the achievement of natural growth.

Concerted cultivation is usually practiced by middle-class parents, regardless of their race. These parents are more likely to be involved in their children's’ education, encourage their children's participation in extracurricular activities or sports teams, and to teach their children how to successfully communicate with authority figures. These communication skills give white children a form of social capital that help them communicate their needs and negotiate with adults throughout their life.

The achievement of natural growth is generally practiced by poor and working-class families, many of whom are Hispanic or African-American. These parents generally do not play as large a role in their children’s education, their children are less likely to participate in extracurriculars or sports teams, and they usually do not teach their children the communication skills that middle- and upper-class children have. Instead, these parents are more concerned that their children obey authority figures and have respect for authority, which are two characteristics that are important to have in order to succeed in working-class jobs.[37]

The parenting practices that a child is raised with has an impact on their future educational achievement. For example, children who are raised with concerted cultivation are exposed to advanced grammar and vocabulary earlier in life, which gives them an advantage over many of their classmates when starting school. Parents who practice concerted cultivation are also more likely to ask their children about what they learned in school each day, and ask for their opinions on different things. This practice gives the children an opportunity to develop and articulate their own thoughts, and these critical thinking skills are important for future academic success.[37]

A child's exposure to technology can also influence their academic performance. In the year 2000, by the time they had reached kindergarten, almost all upper-class children, about half of middle-class children, and fewer than one in five lower-children had used computers. This disparity in technology use is often reflected in the computer literacy practices of the children's parents.[38]

Geographic and neighborhood factors

The quality of school that a student attends can affect a student's academic performance. In the United States, the financing of most public schools is based on local property taxes[39] This system means that schools located in areas with lower real estate values (typically, predominantly Africa-American or Hispanic neighborhoods) have proportionately less money to spend per pupil than schools located in areas with higher real estate values (typically, predominantly Caucasian neighborhoods). This system has also maintained a “funding segregation:” because minority students are much more likely to live in a neighborhood with lower property values, they are much more likely to attend a school that receives significantly lower funding.[39]

Using property taxes to fund public schools contributes to school inequality. Lower-funded schools are more likely to have (1) lower-paid teachers; (2) higher student-teacher ratios, meaning less individual attention for each student; (3) older books; (4) fewer extracurricular activities, which have been shown to increase academic achievement; (5) poorly maintained school buildings and grounds; and (6) less access to services like school nursing and social workers. All of these factors can impact student performance and perpetuate inequalities between students of different races.[40]

However, the achievement gap is not solely caused by this common difference in school quality between Caucasian and minority students. Differences in the academic performance of African-American and Caucasian students exist even in schools that are desegregated and diverse, and studies have shown that a school’s racial mix does not seem to have much effect on changes in reading scores after sixth grade, or on math scores at any age[41]

Cultural factors

Some experts believe that cultural factors contribute to the racial achievement gap. Both Hispanic and African-American youths often receive mixed messages about the importance of education, and often end up performing below their academic potential. Many Hispanic parents who immigrate to America see a high school diploma as being a sufficient amount of schooling and may not stress the importance of continuing on to college. However, counselors and teachers usually promote continuing on to college. This message conflicts with the one being sent to Hispanic students by their families and can negatively affect the motivation of Hispanic students, as evidenced by the fact that Latinos have the lowest college attendance rates of any racial/ethnic group.[42]

African-American students are also likely to receive different messages about the importance of education, but from their peer group and from their parents. Many young African-Americans are told by their parents to concentrate on school and do well academically, which is similar to the message that many middle-class white students receive. However, the peers of African-American students are more likely to place less emphasis on education, sometimes accusing studious African-American students of "acting white." This causes problems for black students who want to pursue higher levels of education, forcing some to hide their study or homework habits from their peers and perform below their academic potential.[42]

Economic factors

Some research has suggested that the disparity in income that exists between minorities and Caucasians directly contributes to the racial achievement gap. The origin of this “wealth gap” is the slavery and racism that made it extremely difficult for African-Americans to accumulate wealth for almost 100 years; a comparable history of discrimination created a similar gap between Hispanics and whites. This results in many minority children being born into low socioeconomic backgrounds, which in turn affects educational opportunities.[41]

Research has shown time and again that that the wealth and income of parents is a primary factor influencing student achievement. A low socioeconomic background can have negative effects on a child’s educational achievement before even starting school; indeed, research has shown that the achievement gap is present between races before starting formal education. On average, when entering kindergarten, African-American students are one year behind Caucasian students in terms of vocabulary and basic math skills, and this gap continues to grow as a child's education continues.[43] A major reason for this is that children in poor families are typically exposed to fewer education-related activities when they are young. This is evidenced by the fact that many minority students begin school with vocabularies that contain much fewer words than the vocabularies of their Caucasian peers. Parents who have less income are less likely to spend money on books for their children, making it difficult for young children to develop their vocabulary skills relative to others.

Economic differences between white and minority families can also perpetuate the racial achievement gap throughout a child’s schooling. Caucasian families are more likely to be able to afford private tutors, SAT or ACT prep classes, and college counselors than Hispanic or African-Americans. These services give Caucasian students another advantage over their minority counterparts and can contribute to differences in grades, test scores, and college attendance rates.[42]

Implications of the Achievement Gap

Individual-based outcomes

The racial achievement gap can hinder the social mobility of minority students. The US Census Bureau reported $62,545 as the median income of White families, $38,409 of Black families, and $39,730 for Hispanic families.[44] The difference in income levels relate highly to educational opportunities between various groups.[45] Students who drop out of high school as a result of the racial achievement gap demonstrate difficulty in the job market. The median income of young adults who do not finish high school is about $21,000, compared to the $30,000 of those who have at least earned a high school credential. This translates into a difference of $630000 in the course of a lifetime.[46] Students who are not accepted or decide not to attend college as a result of the racial achievement gap may forgo over $450,000 in lifetime earnings had they earned a Bachelor of Arts degree.[47] In 2009, $36000 was the median income for those with an associates degree was, $45000 for those with a bachelor’s degree, $60000 for those with a master’s degree or higher.[48]

Beyond differences in earnings, minority students also experience stereotype threat that negatively affects performance through activation of salient racial stereotypes. The stereotype threat both perpetuates and is caused by the achievement gap.[49] Furthermore, students of low academic performance demonstrate low expectations for themselves and self-handicapping tendencies.[50]

Lower education is associated with health-related costs, such as smoking, obesity, and higher consumption of public health resources. The racial achievement gap also leads to less civic engagement through voting. Those graduating from college are 50 percent more likely to vote than those graduating from high school.[51] The majority of US state prison inmates are high school dropouts.[52]

Economic outcomes

The racial achievement gap has consequences on the life outcomes of minority students. However, this gap also has the potential to have negative implications for American society as a whole, especially in terms of workforce quality and the competitiveness of the American economy.[43]

Students with lower achievement are more likely to drop out of high school, entering the workforce with minimal training and skills, and subsequently earning substantially less than those with more education. Today’s economy is also increasingly focused on technology, which means that many employers are having difficulty filling jobs that require strong academic skills. Well-educated citizens are vital to the strength of America’s democracy and economy. Therefore, eliminating the racial achievement gap and improving the achievement of minority students will help eliminate economic disparities and ensure that America’s future workforce is well prepared to be productive and competitive citizens.[53]

Reducing the racial achievement gap is especially important because the United States is becoming an increasingly diverse country. The percentage of African-American and Hispanic students in school is increasing: in 1970, African-Americans and Hispanics made up 15% of the school-age population, and that number had increased to 30% by 2000. It is expected that minority students will represent the majority of school enrollments by 2015.[54] Minorities make up a growing share of America’s future workforce; therefore, the United States’ economic competitiveness depends heavily on closing the racial achievement gap.[53]

The racial achievement gap affects the volume and quality of human capital, which is also reflected through calculations of GDP. The cost of racial achievement gap accounts for 2-4 percent of the 2008 GDP. This percentage is likely to increase as blacks and Hispanics continue to comprise a higher proportion of the population and workforce. Furthermore, it was estimated that $310 billion would be added to the US economy by 2020 if minority students graduated at the same rate as white students.[55] Even more substantial is the narrowing of educational achievement levels in the US compared to those of higher-achieving nations, such as Finland and Korea. McKinsey & Company estimate a $1.3 trillion to $2.3 trillion, or a 9 to 16 percent difference in GDP.[51] Furthermore, if high school dropouts were to cut in half, over $45 billion would be added in savings and additional revenue. In a single high school class, halving the dropout rate would be able to support over 54,000 new jobs, and increase GDP by as much as $9.6 billion.[56] Overall, the cost of high school drop outs on the US economy is roughly $355 billion.

$3.7 billion would be saved on community college remediation costs and lost earnings if all high school students were ready for college. Furthermore, if high school graduation rates for males raised by 5 percent, cutting back on crime spending and increasing earnings each year would lead to an $8 billion increase the US economy.[55]

Efforts to Narrow the Achievement Gap

The United States has seen a variety of different attempts to narrow the racial achievement gap. Some focus on the importance of elementary education, while others have tried to eliminate the gap using federal standards of accountability.

Standards-Based Reform

Standards-based reform has been a popular strategy used to try to eliminate the achievement gap in recent years. The goal of this reform strategy is to raise the educational achievement of all students, not just minorities. Many states have adopted higher standards for student achievement. This type of reform focuses on scores on standardized tests, and these scores show that a disproportionate share of the students who are not meeting state achievement standards are Hispanic and African-American. Therefore, it is not enough for minorities to improve just as much as Caucasians do—they must make greater educational gains in order to close the gap.[53]

One example of standards-based reform was Goals 2000, also known as the Educate America Act. Goals 2000 was enacted in 1994 and aimed to provide resources to states and communities to make sure that all students achieved their full potential. This program set forth eight goals for American students, including increasing the high school graduation rate to at least 90% and increasing the standing of American students to first in the world in achievement in math and science. Goals 2000 also placed an emphasis on the importance of technology, promising that all teachers would have modern computers in their classroom and that effective software would be an integral part of the curriculum in every school. The Goals 2000 program was essentially replaced by No Child Left Behind, and at that time the United States had not met any of the goals explicitly outlined by the program. However, other results were mixed: students demonstrated a higher math proficiency in elementary and middle school, but teacher quality and school safety decreased.[citation needed]

No Child Left Behind

In 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act was put into effect in the United States. This law focuses heavily on standards-based reform: in order to receive federal funding for education, individual states must develop standardized tests to measure student achievement and progress. NCLB also gives families more power over school choice. If their child’s school continually fails to meet Adequate Yearly Progress, parents can choose to send their child to a school that is not failing.

NCLB has shown mixed success in eliminating the racial achievement gap. Although test scores are improving, they are improving equally for all races, which means that minority students are still behind whites. There has also been some criticism as to whether an increase in test scores actually corresponds to improvements in education, since test standards vary from state to state and from year to year.[57]

Institutional changes

Research has shown that making certain changes within schools can have positive impacts on the performance of minority students. These include lowering class size in schools with a large population of minority students; expanding access to high-quality preschool programs to minority families;[53] and focus on teaching the critical thinking and problem-solving skills that are necessary to retain high-level information.[41]

Success stories of narrowing the Racial Achievement Gap

During the 1970s and 1980s, the racial achievement gap between minority and Caucasian students decreased. African-American and Hispanic students made large gains in achievement, while the achievement of white students increased less rapidly. Part of this progress can be attributed to federal programs such as Head Start and Title I which placed emphasis on reducing poverty and improving educational opportunity for poor and minority students.[53] However, some of the progress has been reversed since the late 1980s. One reason for this reversal in progress is that national and state policies and programs did not focus on the racial achievement gap as much during the 1990s.[58] Another reason for this decrease in progress is that Head Start funding has not increased enough in order to keep up with inflation and other changes in the economy, but the program is still expected to produce the same positive results for more students.[59]

Charter Schools

In recent years, certain charter schools have made progress and managed to close the achievement gap in several urban areas. In 1994, two Teach for America alumni started the Knowledge is Power Program, more commonly known as KIPP. KIPP has several unusual policies: students attend school during the summer and on Saturdays, which results in KIPP students being in a classroom 60% more than non-KIPP students. Teachers at KIPP schools also make themselves available much more than most teachers in public schools; they frequently make home visits to get to know the parents of their students, and give their students their cell phone numbers so that students can call with homework questions. The underlying principle of KIPP schools is that “there are no shortcuts.” Students are held to high expectations by their teachers and follow a rigorous curriculum designed to prepare them for college. The minority students who attend KIPP schools have shown much higher test scores, grades, and rates of college enrollment than their non-KIPP minority peers. For example, before entering the KIPP program, only 40% of KIPP students passed their grade level exams. After one year of KIPP, the passing percentage increased to 90%, and the passing rate was almost 100% after just two years in the program. However, some critics have argued that these results are somewhat skewed because KIPP schools tend to serve the minority students with the highest rates of parental involvement and personal motivation.[60]

YES Prep schools are another system of charter schools that have made progress in closing the racial achievement gap. The students who attend YES Prep are primarily minority, low-income students and the schools themselves are located in several low-income areas in and around Houston, Texas. The first graduating class of YES Prep students graduated in 2001, and since then 100% of students who graduate from YES Prep schools enroll in four-year colleges.[citation needed]

See also

- Education in the United States

- Achievement gap in the United States

- Knowledge is Power Program

- YES Prep Public Schools

- No Child Left Behind

References

- ^ http://www.edweek.org/ew/issues/achievement-gap/

- ^ Reardon, S. F., and C. Galindo. "The Hispanic-White Achievement Gap in Math and Reading in the Elementary Grades." American Educational Research Journal 46.3 (2009): 853-91

- ^ Reardon, S. F., and C. Galindo. "The Hispanic-White Achievement Gap in Math and Reading in the Elementary Grades." American Educational Research Journal 46.3 (2009): 853-91

- ^ Clotfelter, Charles T., Helen F. Ladd, and Jacob L. Vigdor. "The Academic Achievement Gap in Grades 3 to 8." Review of Economics and Statistics 91.2 (2009): 398-419.

- ^ Clotfelter, Charles T., Helen F. Ladd, and Jacob L. Vigdor. "The Academic Achievement Gap in Grades 3 to 8." Review of Economics and Statistics 91.2 (2009): 398-419.

- ^ Logerfo, Laura, Austin Nichols, and Sean Reardon. 2006. “Achievement Gains in Elementary and High School.” Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

- ^ Logerfo, Laura, Austin Nichols, and Sean Reardon. 2006. “Achievement Gains in Elementary and High School.” Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

- ^ Logerfo, Laura, Austin Nichols, and Sean Reardon. 2006. “Achievement Gains in Elementary and High School.” Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

- ^ Logerfo, Laura, Austin Nichols, and Sean Reardon. 2006. “Achievement Gains in Elementary and High School.” Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

- ^ a b Camara, W.J., & Schmidt, A.E. (1999). Group differences in standardized testing and social stratification (College Board Report No. 99-5). New York: The College Board.

- ^ Hedges, L.V., & Nowell, A. (1998). Black-white test score convergence since 1965. In C. Jencks & M. Phillips (Eds.), The black-white test score gap. (149–81). Washington, DC: The Brookings Institute

- ^ a b Alan Vanneman, Linda Hamilton, Janet Baldwin Anderson, Taslima Rahman (2009). Achievement Gaps: How Black and White Students in Public Schools Perform in Mathematics and Reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. NCES

- ^ a b Hemphill, F., Vanneman, A., Rahman, T. (2011). How Hispanic and White Students in Public Schools Perform in Mathematics and Reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. NCES.

- ^ Scott, Leslie A.; and Ingels, Steven J. (2007). Interpreting 12th-Graders’ NAEP-Scaled Mathematics Performance Using High School Predictors and Postsecondary Outcomes From the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988 (NELS:88)

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Natl. Cent. Educ. Stat. 1997. Digest of Educaion Statistics. U.S. Dep. Educ.: Off. Educ. Res. Improv.

- ^ Miller LS. 1995. An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ Miller LS. 1995. An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ Miller LS. 1995. An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). The Condition of Education 2011 (NCES 2011-033), Indicator 21.

- ^ U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). Digest of Education Statistics, 2010 (NCES 2011-015), Chapter 3 .

- ^ House, G. (2011). Transforming America's High Schools. Strategies for Creating and Sustaining Meaningful Reform. http://www.ncchamber.net/docs/pdfs/EDUsummit_DrHouse.pdf

- ^ The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. Black Student College Graduation Rates Remain Low, But Modest Progress Begins to Show. http://www.jbhe.com/features/50_blackstudent_gradrates.html

- ^ Jencks C, Phillips M. 1998. The black-white test score gap: an introduction. In The Black- White Test Score Gap: an Introduction, ed. C Jencks, M Phillips. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst.

- ^ Miller LS. 1995. An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ Jencks C, Phillips M. 1998. The black-white test score gap: an introduction. In The Black- White Test Score Gap: an Introduction, ed. C Jencks, M Phillips. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst.

- ^ Jencks C, Phillips M. 1998. The black-white test score gap: an introduction. In The Black- White Test Score Gap: an Introduction, ed. C Jencks, M Phillips. Washington, DC: Brookings Inst.

- ^ a b c The Nation's Report Card. 2008 Long Term Trend Report Card. http://nationsreportcard.gov/ltt_2008/ltt0001.asp

- ^ Chudowsky & Kober. (2007). Are Achievement Gaps Closing and Is Achievement Rising for All? Center on Education Policy.

- ^ a b Rothstein, Richard. 2004. Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic, and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap. Washington, D.C: Economic Policy Institute.

- ^ a b Lareau, Annette. 2003. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Rathburn, Amy, and Jerry West. 2003. Young Children's Access to Computers in the home and at School in 1999 and 2000. NECS 2003-036. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

- ^ a b Massey, Douglas S. 2004. “The New Geography of Inequality in Urban America,“ in C. Michael Henry, ed. Race, Poverty, and Domestic Policy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Kozol, J. 2005. Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America. New York: Crown.

- ^ a b c Singham, Mano. 2005. The Achievement Gap in U.S. Education: Canaries in the Mine. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

- ^ a b c Noguera, Pedro A. 2008. The Trouble with Black Boys. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- ^ a b Espenshade, Thomas J. and Alexandria Walton Radford. 2009. No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal: Race and Class in Elite College Admission and Campus Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ US Census. Table 697. Money Income of Families—Median Income by Race and Hispanic Origin in Current and Constant (2009) Dollars: 1990 to 2009. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0697.pdf

- ^ Katz & Rodin (2012). Targeting an Achievement Gap in One of the Country's Most Educated Metros. http://m.theatlanticcities.com/jobs-and-economy/2012/01/achievement-gap-one-countrys-most-educated-cities/983/

- ^ Rouse, C.E., (2007). Quantifying the Costs of Inadequate Education: Consequences of the Labor Market. In C.R. Belfield and H.M. Levin (eds.), The Price we Pay: Economic and Social Consequences of Inadequate Education (pp.99-124). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

- ^ Pilon, Mary (2010). What's a Degree Really Worth? http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703822404575019082819966538.html

- ^ U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). The Condition of Education 2011 (NCES 2011–033), Indicator 17.

- ^ Aronson, J. (2004). The Threat of Stereotype. Closing Achievement Gaps, 62 (3), 14-19.

- ^ Zuckerman, M., Kieffer, S., Knee, C.R. (1998). Consequences of Self-Handicapping: Effects on Coping, Academic Performance and Adjustment. 74 (6), 1619-1628.

- ^ a b McKinsey & Company. The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America's Schools. http://mckinseyonsociety.com/downloads/reports/Education/achievement_gap_report.pdf

- ^ National Dropout Prevention Center. Economic Impacts of Dropouts. http://www.dropoutprevention.org/statistics/quick-facts/economic-impacts-dropouts

- ^ a b c d e Kober, Nancy. 2001. “It Takes More Than Testing: Closing the Achievement Gap.” Washington, D.C: Center on Education Policy.

- ^ Ornstein, Allan C. 2010. “Achievement Gaps in Education.” Social Science and Public Policy 47 (5): 424-429.

- ^ a b Alliance for Excellent Education (2009). Potential Economic Impacts of Improved Education on the United States. http://www.all4ed.org/files/National_econ.pdf

- ^ Alliance for Excellent Education, “Education and the Economy: Boosting the Nation’s Economy by Improving High School Graduation Rates” (Washington, DC: Author, 2011).

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/29/education/29scores.html

- ^ Lee, Jaekyung. 2002. "Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gap Trends: Reversing the Progress Toward Equity?" Educational Researcher 31(1): 3-12.

- ^ Barnett, W. Steven. 2002. "The Battle Over Head Start: What the Research Shows." Washington, D.C: Congressional Science and Public Policy Briefing.

- ^ Mathews, Jay. 2009. Work Hard, Be Nice: How Two Inspired Teachers Created the Most Promising Schools in America. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

External links

- [1] Education Week: Achievement Gap

Category:Education issues Category:Education in the United States Category:Race in the United States Category:Social inequality