The End of Illa

| |

| Author | José Moselli |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | John Schoenherr |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Science fiction Utopia |

| Published | 1925 |

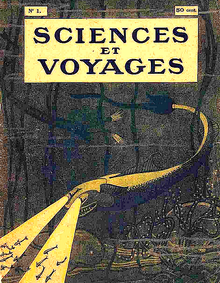

| Publisher | Sciences et Voyages |

The End of Illa (French: La fin d'Illa) is a novella by the French writer José Moselli, published in 1925.

The novel begins with marines discovering a manuscript on a Pacific atoll, which reveals the existence of an advanced civilization that no longer exists today. The narrator, the military chief Xié, recounts the last days of the city of Illa when the city, led by its dictator Rair, went to war against the neighboring city Nour.

Classified as scientific marvel and utopian literature, this novel reinterprets the myth of Atlantis. José Moselli addresses themes of technological advance and its social consequences. In effect, the installation of a dictatorship and the moral decadence that accompanies scientific progress lead progressively to the self-destruction of the brilliant civilization of Illa.

The story, published initially in serial form in the magazine Sciences and Voyages between January 29 and July 9, 1925, is illustrated by the artist André Galland. The novel was republished numerous times in France during the second half of the 20th century, but was not translated into English until the 21st century.

Background

After a career in the merchant marine, José Moselli met in 1910 one of the Offenstadt brothers, who suggested writing an adventure novel.[1] Their collaboration proved fruitful, and José Moselli rapidly became a leading author for the Offenstadt brothers.[2]

During his literary career, Moselli wrote nearly a hundred episodic novels for magazines published by Offenstadt, like The Splendid, The Intrepid, The Little Illustrated, or Cry-Cry.[3] Thus, when the two brothers launched the magazine Sciences and Voyages on September 4, 1919, they asked him for short writings belonging to the fantastic subgenre.[2] José Moselli therefore started the publication of Ice Prison (1919–1920) in the first edition of the magazine; for many years afterward, he furnished the magazine with The "Phi" Ray (1921), The Conquerors of the Abyss (1922), or in its annual supplement (The Scientific Almanach) with The Eternal Voyage or the Prospectors of Infinity (1923) and The Messenger from the Planet (1924).[4]

At the time The End of Illa was published, the Offenstadt brothers were launching a defamation lawsuit against the abbot Calippe, who had categorized Sciences and Voyages as dangerous for youth in his newspaper. This court case was one of many undertaken by the Offenstadts with the goal of preserving the youth market of Sciences and Voyages. As with the previous lawsuits, on May 27, 1924, the Amiens court rejected the lawsuit on the basis that the novels and articles the magazine published had nothing scientific about them, and could consequently have a pernicious effect on the imagination and intelligence of children.[5] Science fiction essayist Jacques Van Herp believed this court case may have led Moselli to self-censor and reduce the scope of the described inventions in the novel.[6]

Science fiction writings represented only a part of Moselli's work; he wrote mostly adventure novels.[7] Nevertheless, between 1919 and 1929, he published ten conjectural novels in Sciences and Voyages.[8]

Summary

Prologue: Grampus Island

On March 22, 1875, the American whaler Grampus is sailing the Pacific under the command of Captain Ellis when it discovers an unlisted islet. The crew disembarks to find potable water and discover, in the middle of the vestiges of an ancient civilization, a violet stone made of an unknown substance as well as a manuscript written in a mysterious alphabet. Returning to San Francisco, Captain Ellis recounts his discovery, which nobody takes seriously. The manuscript and stone are sold to Doctor Akinson for a meager price.

For 30 years, the doctor works on these two objects to discover their secret, to the point of exhausting all his financial resources. It is not until April 1905 that he finally deciphers the first part of the manuscript. This part recounts the life of a certain Xié, an inhabitant of Illa, an ancient and very technologically advanced city which completely sank into oblivion. The doctor Akinson sends his translated manuscript to a colleague in Washington on May 5, 1905, later reporting the translation of the second part, which contains all the science and novel mathematical formulas discovered by the brilliant civilization of Illa. However, Akinson's servant, persuaded that he was sinking into madness, throws both the manuscript and the violet stone into the fire. The strange stone explodes and destroys a large portion of San Francisco. Meanwhile, the translation arrives at the home of Doctor Isambard Fullen, a Harvard professor. However, the professor dies before ever reading the translation, so it is sold to a bookstore in New York before being finally delivered to readers.[9]

First part: The Blood War

The manuscript is authored by Xié, head of Illa's armies, with the goal of explaining the end of Illa to future generations. His story starts with a meeting of the Grand Supreme Council during which the leader of Illa, Rair, informs the audience of his plan to wage war against the neighboring city of Nour. As inventor of the blood machines[Note 1] Rair now wishes to feed his machines with Nourians instead of animals, which would considerably prolong the life expectancy of Illians.[10]

Disgusted by Rair's projects, Xié goes back home and discovers that his daughter Silmée had just escaped an attempted assassination. After discussing with Toupahou, her fiancé and Rair's grandson, Xié and Toupahou conclude that they must put an end to the actions of Rair, who likely instigated the attack.[11]

Deciding not to compromise with Rair, Xié joins Fangar, head of the air force, to prepare the offensive against the rival city. He learns that Rair chose to use "monkey men", genetically modified individuals who do the most thankless of Illa's jobs, to pilot the flying shells. When he goes back home, his daughter Silmée had disappeared.[12]

After several hours of intolerable waiting, Xié receives a visit by the head of the militia, Grosé, who had come to arrest him for negligence. In fact, during the preparation of the assault against Nour, he had been surprised by Limm, head of Rair's secret police, while he was not performing his arms verification duties. He is imprisoned in a minuscule cell. Well afterwards, when he had lost all sense of time, Xié is secretly freed by Fangar. However, while the two men are escaping on board a flying engine, the machine suddenly stops flying and starts to fall.[13]

Thanks to Fangar's ability, the two men manage to land without damage. After learning that his 7 week detention could not have ended without information from Grosé, Xié rejoins a seditious group opposed to Rair's dictatorship.[14]

Hidden in the stables that house animals destined to feed the blood machines, Xié and Fangar are joined by Grosé and Foug, a member of the Supreme Council, who tells them that the head of electric devices, Ilg, had deserted to Nour, taking a piece of zero-stone with him. The theft of this mineral of extreme destructive potential motivates Rair to try to ally with Xié for the purpose of subjugating the Nourians as quickly as possible. To free his daughter Silmée and protect Illa from an imminent peril, Xie agrees to retake command of the Illian army.[15]

The next day, Xié launches the offensive by sending flying shells guided by monkey men toward Nour. However, warned by Ilg, the king Houno had evacuated the city just before its destruction. In reprisal, Nour's air force approaches Illa, but Xié sends flying shells to meet it. Profiting from the enthusiasm of Illians, who saw the Nourian offensive fail, Rair publicly announces that he had improved the blood machines so that by feeding them the blood of future prisoners of war, they could prolong Illians' life expectancy by one century. He therefore announces his wish to extend the conflict to the neighboring cities of Aslur and Kisor. Although Illa falls asleep in joy, cries and panic soon overtake the streets.[16]

Attacking from under ground by surprise, the Nourians spread asphyxiating gas inside the houses. Disoriented by the disappearance of his daughter and after having just escaped a land torpedo, Xié takes charge of the excavation work to find the Nourians.[17]

Faced with panicked Illians looking to take refuge inside the Grand Pyramid, Rair sends his monkey men to slaughter his fellow citizens, accentuating the panic and the terror. Xié intervenes to neutralize the dictator and subsequently takes command of the city. Thanks to his level headedness, he is able to decimate the Nourian air force using "radioactive vibrations". He could not savor this victory, however, because he is soon overwhelmed by Rair's monkey men, allowing Rair to retake power. Xié is then condemned for attempted assassination of Rair and sent into the mines to work alongside the monkey men.[18]

Second part: The Mines

While Xié is tortured, then sent into the metal mines, Rair obtains the complete surrender of the Nourians, who are forced to deliver prisoners of war to feed the blood machines.[19]

While he resigns himself to his new life of labor and violence, Xié manages nevertheless to befriend a monkey man named Ouh. Ouh teaches him the secret language of the slaves and gives him tips for survival. Provided with allies, he then prepares his escape. Xié incites 3000 monkey men to revolt and, after many losses, succeed in taking control of the mine.[20]

After taking control, the insurgents manage to leave the mine by the access wells. Massacring every human on the way, including the militiamen and engineers responsible for the blood machines, Xié and only a dozen monkey men reach the surface of the city.[21]

During his escape, Xié encounters Limm and assassinates him. He then seizes the spy's identification plaque and weapon, in order to pass checkpoints. On the pretext of carrying out an inspection, he flees on board an aircraft and leaves Illa in the direction of Nour. After landing his flying engine, he pursues an individual on foot, who attacks him. Easily neutralizing him, he discovers, stunned, that it is his friend Fangar, who had succeeded in fleeing and hiding in this Nourian region. In agony, Fangar tells Xié just before dying that Silmée and Toupahou are still alive and hiding in Nour.[22]

Arriving in a devastated Nour, Xié steals and kills to meet his needs. He goes to the place indicated by Fangar and falls across the traitor Ilg, who reveals to him where his daughter and her fiancé are. After reuniting with them, Xié sends Toupahou to Illa to negotiate their return with his grandfather Rair. A few days later, learning that her fiancé was executed on arrival, Silmée kills herself. Deciding to take vengeance, Xié goes back to Illa. He discovers a city devastated after the revolt of the monkey men, a revolt which stopped the extraction of the mineral necessary for the blood machines to function well. Xié ends his manuscript in declaring his intention to destroy Illa by causing a zero-stone explosion, and bequeathing his writing to posterity.[23]

The writing concludes on a note by the author, who recounts that when Doctor Akinson's servant threw the manuscript and stone (which was visibly a fragment of zero-stone) into the fire on May 5, 1905,[23] the city of San Francisco was destroyed.[Note 2]

Principal characters

The story is introduced by a long prologue aiming to explain how the author found himself in possession of the manuscript. Said manuscript was discovered by marines, then sold to Professor Akinson, a doctor who would dedicate his entire life to its translation. Managing to decipher the writing, he unfortunately could not profit from the discovery because he was killed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906.[24]

The main character of the novella is named Xié. Narrator of the story, he is the commander in chief of the armies of an ancient city named Illa. He is split between his loyalty toward his fatherland and his hatred for the man who leads it, Rair. In fact, despite his military rank, he vigorously opposes the amoral methods of the dictator and finds no way out of his revolt other than a final holocaust.[7] Described as a polymorphous character—he becomes in turn head of the armies, traitor, and slave—he possesses characteristics of the heroes of popular novels and permits the reader to identify themselves with his fate. In appearing as a courageous rebel who transcends his military career, he is the last rampart against the moral decadence of his city.[25] Beyond his will to protect his daughter Silmée and her fiancé Toupahou (also grandson of Rair), Xié also revolts against the leader of Illa. He is joined in his struggle by several allies, including Grosé, head of the militia, and Fangar, head of the air force, his only real friend, whom he accidentally kills.[7] In the end, he allies himself with the monkey men, a population of slaves derived from an ancient cross between black populations and monkeys; in particular he allies with his slave companion Ouh, whom he trains during the insurrection.[25]

Living at the summit of a pyramid, the leader of Illa, Rair, is also a genius inventor.[26] A cold-blooded dictator figure devoid of morality,[27] he starts a war against the neighboring city of Nour, for the purpose of obtaining prisoners of war to feed his blood machines and thereby prolong the life of Illians.[28] His second-in-command is Limm, head of his secret police, who vows a ferocious hatred against Xié.[29]

Style and literary movement

Narrative methods

This novel, which reveals the existence of a lost ancient civilization, is recounted in the form of a flashback.[30] In effect, while the prologue, which starts from the beginning of the 20th century, recounts how the narrator found himself in possession of a manuscript written by Xié, an inhabitant of the city of Illa, the following parts of the novel are a first-person account by Xié himself. It was the second time that José Moselli wrote his story in first person, after the novel The Last Pirate appearing the previous year.[7]

In addition, the author relates his story to a recent event to anchor it in the real world. He explains that the destruction of San Francisco in 1906 was not the work of an earthquake, but instead caused by the explosion of a zero-stone fragment—previously at the origin of the annihilation of Illa—which was found at the same time as the writings of Xié.[31]

Initially published in series form in a magazine, the novel consists of 23 separate parts.[30] José Moselli takes advantage of the format to not only construct a story at a sustained pace with multiple adventures and twists, but also to end each part with a cliff-hanger that hooks readers.[3] In general, the series format demands a certain writing style. Its format is sensitive to frequent edit requests from the editor, himself subject to the readers' expectations.[32] This editorial reality could explain why the last chapters seem to be sloppy.[7]

Moselli delivered a strongly outlook in this novel.[33] In his tragic story, the main character sees his career break down; just as he is lifting himself up, he sees his daughter and only friend die, the latter of which he accidentally killed himself.[7] The author, in addition, uses spatiality to construct his story. He opposes Rair, living at the summit of his pyramid, with Xié, thrown into Illa's underground to work alongside the monkey men slaves.[26] Beyond the personal tragedy, Moselli juxtaposes the tragedies that befall Xié and Illa throughout the entire novel and mirrors trials suffered by the character with different stages in the destruction of the city.[25]

Dystopian anticipation, a scientific marvel literature

A series writer specializing in adventure novels,[2] Moselli wrote in 1925 that this novella belongs to the scientific marvel genre.[34] Considered as the masterpiece of his conjectural writings,[35] The End of Illa illustrates a certain number of recurrent themes of this scientific marvel genre which developed in France since the end of the 19th century, with themes such as lost worlds, utopias, devastating wars, and more generally the extrapolation of scientific discoveries.[36] Thus, through these themes, José Moselli retold the myth of Atlantis, recounting the tragic destiny of an ancient but technologically advanced city and its engulfment by the ocean.[30]

While the main plot is situated in the past, the novel is nevertheless considered as a writing of anticipation. In effect, the author places his writing in the retrofuturist framework, in which he traces the past disappearance of a highly technological society. Thus, the description of this Illian society permits the reader to identify it as one of the possible futures.[37] The story relies upon evoking anxieties that existed in the 1920s: the incessant progress of technology and the European political situation.[38] According to Philippe Curval, the 1925 novel accomplishes the feat of anticipating, twenty years in advance, the horrors instigated by the Third Reich.[3] Critics[29] also point out that its success in anticipating the future is found even in its choice of names, as the dictator of Illa, Rair, sounds similar to Hitler in French, and Rair's head of secret police, Limm, evokes the name of Himmler.

Aside from its belonging to the anticipation genre, The End of Illa can also be classified as an utopian novel, as the author strives to depict a society which appears ideal due to its abundance of inventions.[39] However, from the beginning of the story, it is the dystopian dimension which is put in the forefront, with its description of the Illian citizens' psychological dependence on the blood machines, and therefore on its inventor, the dictator Rair.[40] For Moselli, telling a story that takes place in the past allows him to emphasize the utopian nature of the city, notably establishing a parallel with the ancient Atlantis. Like it, Illa is a paradoxical society, criss-crossed by dueling forces, where technological prowess accompanies the boredom of the citizens, whose comfort is lied to the dictatorship of one man.[27]

Themes

A very technologically advanced civilization

_Plakat_für_den_Film_Metropolis,_Staatliche_Museen_zu_Berlin.jpg/440px-1927_Boris_Bilinski_(1900-1948)_Plakat_für_den_Film_Metropolis,_Staatliche_Museen_zu_Berlin.jpg)

In The End of Illa, José Moselli describes an ancient and very scientifically advanced civilization, whose technology has today entirely disappeared.[31] Through the description of a grandiose and futuristic city, a real Metropolis, the author takes stock of multiple technological innovations that the inhabitants take great comfort from.[3]

The most emblematic of this world's inventions relates to the feeding of Illa's citizens. Having gotten rid of all solid food, the citizens are directly fed by waves generated by the "blood machines".[24] These devices use the blood of pigs and monkeys, which they transform into an energy which is spread throughout the whole city. What's more, it is the improvement of this invention which leads to the war between Illa and its neighbor Nour. The Illian leader and inventor of the blood machines, Rair, manages to perfect these machines. These new versions, which now work with human blood, are not only much more efficient, but can also prolong the average human life by a century. Thus, it is for obtaining human lives that Illa declares war against the city of Nour.[28]

Although smaller than its neighbor Nour with which it disputes hegemony, Illa is an immense megapolis 17 km in diameter and 700 m in height.[41] Habitations, situated under the surface, are covered by an immense terrace which captures the Sun's rays to assure the lighting of the city. At the center of this terrace stands a pyramid, the seat of government. To facilitate transportation for the inhabitants, the floors of the habitations produce magnetic emanations which suppress weight by nine tenths.[24]

In the end, Illian military power rests equally on its technology. Besides its fleet of flying shells—airplanes composed of a very light metal (the metal-par-excellence) and which can contain up to eight bombs[24]—the city has mastered the science of zero-stone, which has the devastating explosive power of an atomic bomb.[28]

A society that crosses all moral bounds

While the Illian civilization has perfected itself scientifically, it has instead degraded morally.[42] Moselli, with this novel, denounces the scientific progress that becomes barbarity when it denies the individual.[39] In Rair's regime, the individual no longer counts; enjoying a bored comfort, he is no longer anything but an amorphous cell of the state. In obliterating human value, condemnations of criminals become moments of spectacle during which their arms are dissolved in acid; political opponents, reduced to the rank of beasts, are degraded.[42] It is in addition this moral decadence that is at the origin of the city's fall.[24] Moselli spotlights this scientific amorality which, when it is solely at the service of personal ambition, ultimately proves self-destructive.[25]

The entire social structure of Illa is founded on eugenic practices, in particular thanks to the use of slaves.[25] All the undesirable tasks and hard labor are left to a genetically modified population, the monkey men,[28] descendants of a black population that the experts had made to regress toward a primitive stage:[25]

By appropriate food, by wisely dosed exercises, we succeeded in atrophying the brain of these anthropoids and boosting the strength and endurance of their muscles. A monkey man can lift 700 kg and work 5 days without stopping on the hardest tasks, without attaining the limit of his abilities.[43]

Also, the use of blood machines illustrates the immorality which the citizens of Illa are capable of in the name of improving their comfort. Though this vampirism relies initially on the transformation of animal (pig and monkey) blood into a nourishing flow, the Illians accept the use of human blood to augment their lifespan. The war against neighboring Nour is the consequence of the need to provide human victims.[33] Moselli describes a truly bloody power in Rair, as he accepts the sacrifice of a part of his population, through violent scenes of massacre and destruction, to achieve his objectives.[31] The revolt of the story's narrator, Xié, embodies the opposition to this inexorable depravation of Illa. Head of armies, the military man still refuses to cross the moral limit of feasting on the blood of his enemies.[3]

This moral decadence of Illa's inhabitants illustrates, in the eyes of Moselli, the cruel nature of mankind. Man, whatever his geographic origin or his era, whether he lives in an industrial or a primitive society, is completely ready to sacrifice his fellow to improve his comfort. This unchanging characteristic of man is indeed not corrected in the slightest by scientific advances.[44] To the contrary, Rair, a scientist morally perverted by power, uses science to reinforce his exercise of supreme power.[25]

The seeds of totalitarianism

Moselli portrays a truly totalitarian political system in Illa.[45] It is thanks to his total control of technological development that Rair manages to assert his power over the masses.[27] The desire of Moselli to represent the alliance between power and science in the popular novel took place in the context of an evolution in literary tropes. In the 19th century, the myth of Prometheus was incarnated in the figure of the mad scientist; starting in the 20th century, the mad scientist was replaced by the equally worrying figure of the tyrant.[45]

The character of Rair, an unjust and authoritarian tyrant,[27] succeeds in enlisting scientists in the service of his power. The members of the Illa Council—which forms the city's government—should have been the guarantors of conscientious use of science, but are equally perverted by the promises of Rair.[46] In fact, the creation and improvement of the blood machines is his most powerful tool for consolidating power in his dictatorial regime. Having become incapable of nourishing themselves with solid food like monkey men do, the people are totally dependent on this invention. Thus, debased by this dependence, they support the disastrous projects of Rair.[42]

After the treason of Ilg, who not only revealed Rair's plans of waging an offensive against Nour, but also brought a fragment of zero-stone to the Nourian government, the dictator of Illa decides to engage in a preventative war against his neighbor. Following its failure, he does not hesitate to sacrifice Illa's populace to consolidate his authority.[28] Suffering the assault of Nourian forces, Rair panics and massacres the citizens of Illa who, fleeing their subterranean homes invaded by gas, sought to find refuge in the pyramid, the seat of government. In this mindset, he would rather accelerate the destruction of the city than lose power.[42] Finally, triumphing over Nourian forces thanks to the intervention of Xié, Rair eliminates his last opponents and installs his reign of terror.[28]

Publication history and legacy

Considered one of Moselli's major works,[47] The End of Illa appears for the first time in edition 283 of the magazine Sciences and Voyages of January 29, 1925. Embellished by illustrations from André Galland, the novel was published in 23 parts, until edition 306 of July 9, 1925.[Note 3][48]

In 1962, under the influence of Jacques Bergier and Francis Carsac,[3] the novel was published in two parts, in editions 98 and 99 of the magazine Fiction, specializing in imaginative literature. At the start of the 1970s, the novel was republished two times. The first was in 1970, when it was published by Éditions Rencontre in the series "Masterpieces of science fiction", alongside the new The Messenger from the Planet and The City of the Chasm.[49] Then, in 1972, it was republished by the Marabout publishing house in the collection "Marabout Library—Science fiction".

The End of Illa was again republished two times in the middle of the 1990s. The Grama publisher edited the work, added illustrations by Denis de Rudder, and published it in their collection "The Past of the Future" in 1994, while the next year, the Omnibus publisher included Moselli's novella in the anthology Atlantises, Engulfed Islands alongside numerous writings relating to the theme of Atlantis.[4]

In 1994, in a postscript written during the reissuing of the work by the Grama publisher, the science fiction essayist Jacques Van Herp argues that this novel was the origin of the temporary decline of French science fiction, on the grounds that it was suspected of perverting the youth.[6] Even though this hypothesis is contested[3]—or at least taken with precaution—it testifies to the progressive disappearance of stories of scientific imagination starting from the 1930s,[50] notably through the practice of self-censorship by authors.[6]

Aside from this possible influence on the genre, the novel nevertheless appears today as a prophetic work which anticipated through the story of Rair and his aggressive war the actions of Hitler, with his Blitzkrieg maneuvers 15 years later.[26]

Despite regular republications in France in the second half of the 20th century, the novel was not exported abroad in the same period. It was only in 2011 that the work was translated into English by Brian Stableford and published by Black Coat Press.[51]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Blood machines, invented by Rair, turn the blood of pigs and monkeys into waves, which then nourish the Illian population.

- ^ An editor's note states that José Moselli is making an allusion to the earthquake suffered by San Francisco on April 18, 1906.

- ^ Publication was interrupted in edition 287 of Sciences and Voyages.

References

- ^ George Fronval (1970). "José Moselli, sa vie son œuvre". Le Chasseur d'illustrés (in French). Vol. Moselli special.

- ^ a b c Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 144.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Philippe Curval (April 1995). "José Moselli: la Fin d'Illa". Magazine littéraire (in French). No. 331.

- ^ a b Costes & Altairac 2018, p. 1478.

- ^ "Carnet de la Revue". Revue des lectures (in French). No. 1. January 15, 1926. pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b c Serge Lehman (2006). "Hypermondes perdus". Chasseurs de chimères, l'âge d'or de la science-fiction française (in French). Paris: Omnibus. pp. XX–XXI. ISBN 9782258070486.

- ^ a b c d e f Lathière 1970.

- ^ Brantone, René; Hermier, Claude (2000). "Bibliographie de José Moselli : classement par revues". José Moselli, sa vie, son œuvre. L'Œil du sphinx.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 15–39, Prologue.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 41–54, I/1.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 54–66, I/2.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 67–79, I/3.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 80–92, I/4.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 93–106, I/5.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 106–119, I/6.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 119–132, I/7.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 132–145, I/8.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 145–157, I/9.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 159–166, II/1.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 166–185, II/2.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 185–198, II/3.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 198–211, II/4.

- ^ a b Moselli 1970, pp. 211–224, II/5.

- ^ a b c d e Costes & Altairac 2018, p. 1473.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e f Van Herp 1974, p. 91.

- ^ a b Van Herp 1972, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Valérie Stiénon (December 21, 2012). "Dystopies de fin du monde. Une poétique littéraire du désastre" (PDF). Culture, le Magazine Culturel de l'Université de Liège. p. 7.

- ^ Brian Stableford (2011). "Brian Stableford : préface et postface à l'édition américaine du Mystère des XV". Nyctalope ! L'Univers extravagant de Jean de La Hire. Black Coat Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-61227-016-6.

- ^ a b Costes & Altairac 2018, p. 1474.

- ^ "Le Merveilleux-scientifique. Une science-fiction à la française – Bibliographie sélective" (PDF). bnf.fr (in French). April 2019. p. 10.

- ^ Pierre Versins (1972). Encyclopédie de l'utopie, des voyages extraordinaires et de la science-fiction. Lausanne: L'Âge d'Homme. p. 85. ISBN 978-2-8251-2965-4.

- ^ Jean-Luc Boutel (2015). "La littérature d'imagination scientifique : genèse et continuité d'un genre". In Jean-Guillaume Lanuque (dir.) (ed.). Dimension Merveilleux scientifique. Encino (Calif.): Black Coat Press. pp. 325–326. ISBN 978-1-61227-438-6.

- ^ Stiénon, Valérie (2018). "Un roman de la rumeur médiatique. Événement, suspense et anticipation dans Le Péril bleu de Maurice Renard". ReS Futurae. No. 11.

- ^ Van Herp 1974, p. 92.

- ^ a b Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 152.

- ^ Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 147.

- ^ Moselli 1970, pp. 42–43, I/1.

- ^ a b c d Van Herp 1972, p. 184.

- ^ Moselli 1970, p. 54, I/2.

- ^ Jacques Van Herp (1996). "José Moselli et les terres polaires". Les Carnets de l'exotisme. No. 17–18. p. 148.

- ^ a b Alexandre Marcinkowski (2018). "Avant-propos". C'était demain: anticiper la science-fiction en France et au Québec (1880–1950). Pessac: Presses universitaires de Bordeaux. p. 14. ISBN 979-10-91052-24-5.

- ^ Vas-Deyres 2013, p. 151.

- ^ Van Herp 1972, p. 183.

- ^ Denis Blaizot (February 18, 2018). "Sciences et voyages 1924–1925". Gloubik Sciences.

- ^ Moselli, José (1970). La fin d'Illa. Rencontre.

- ^ Jean-Luc Boutel (2015). "La littérature d'imagination scientifique : genèse et continuité d'un genre". Dimension Merveilleux scientifique. Encino (Calif.): Black Coat Press. p. 340.

- ^ "Title:La fin d'Illa". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

Bibliography

- Patrick, Bergeron; Guay, Patrick; Vas-Deyres, Natacha (2018). C'était demain: anticiper la science-fiction en France et au Québec (1880–1950) (in French). Pessac: Presses universitaires de Bordeaux. ISBN 979-10-91052-24-5.

- Valérie Stiénon, "Des années folles ? : L'écriture de la catastrophe de Claude Farrère à Léon Groc", pp. 183–193.

- Alexandre Marcinkowski, "L'incubation totalitariste dans la littérature d'anticipation française de l'entre-deux-guerres : le cas exemplaire de La fin d'Illa de Moselli", pp. 277–294.

- Costes, Guy; Altairac, Joseph (2018). Rétrofictions, encyclopédie de la conjecture romanesque rationnelle francophone, de Rabelais à Barjavel, 1532–1951 (in French). Vol. 1 : lettres A à L, t.2 : lettres M à Z. Preface by Gérard Klein. Amiens / Paris: Encrage / Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-44851-0.

- Lathière, René (1970). "José Moselli et la science-fiction". Le Chasseur d'illustrés. No. Moselli special.

- Van Herp, Jacques (1972). "Postface : José Moselli, l'écrivain sans livre". La Fin d'Illa. By José Moselli. Marabout. pp. 167–186.

- Van Herp, Jacques (1974). Panorama de la science-fiction: Les thèmes, les genres, les écoles, les problèmes. Verviers: Éditions Gérard & Co.

- Van Herp, Jacques (1994). "Postface : José Moselli et la SF". La Fin d'Illa. By José Moselli. Grama. pp. 169–190..

- Vas-Deyres, Natacha (2013). Ces Français qui ont écrit demain: utopie, anticipation et science-fiction au XXe siècle. Paris: Honoré Champion. ISBN 978-2-7453-2666-9.