Territorial evolution of Ethiopia

Beginning with the Kingdom of Aksum, Ethiopia's territory evolved significantly through conquest of the lands surrounding it. Strong Aksumite trading partnerships with other world powers gave prominence to its territorial expansion. In 330, Aksum besieged the Nubian city of Meroë, marking the beginning of its great expansion. It finally declined after the rise of Islamic dominion in South Arabia, and it ultimately collapsed in the 10th century.

The Zagwe dynasty emerged and ruled until 1270, when Amhara-Shewan Yekuno Amlak revolted against the last king, Yetbarak, commencing the Solomonic dynasty-led Ethiopian Empire. The empire reached its greatest extent under the emperors Amda Seyon I and Zara Yaqob. In 1896, Emperor Menelik II’s conquest strongly consolidated Ethiopia’s modern borders while eluding the 19th-century Scramble for Africa and Italian colonialism. Eritrea was annexed by the Ethiopian imperial government under Emperor Haile Selassie in 1952, culminating in the Eritrean War of Independence. Eritrea eventually seceded by referendum during its seizure by the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) in 1993.

Aksumite Empire

Aksum as an empire grew trade connections and subsequently expanded its territory. The Red Sea had influenced trade routes since the first millennium BC and still did into the Christian era. Aksumite commodities were primarily elephant tusks, exported through the Mediterranean, Middle East and Levant, as traders swept west from the African interior. In the past, the South Arabian population settled in core places of Aksum such as Koloe, Matara, Atsbi, and Yeha.

An anonymous ruler undertook northerly conquest "beyond the Nile in inaccessible mountains covered with snow" where "Samien people" dwelled. When Aksumite control of the Red Sea intensified, Aksum was classified as a great power in the late 3rd century, as evidenced by Monumentum Adulitanum, and supported by Stuart Munro-Hay.[1] In 330, Aksum completely sacked Meroë under King Ezana of Axum, marking the period of territorial expansion, together with his predecessor Ousanas.[2]

Himyar Jewish king Dhu Nuwas attempted to invade Yemen by massacring Aksumite Christians and burning churches, and King Kaleb launched a military expedition in 518 that successfully soothed Yemen by defeating him and securing the Aksumite territory of Yemen.[3]

Medieval Muslim expansions

The downfall of Aksum led to a political vacuum in central and southern Ethiopia and paved the way for the establishment of Muslim sultanates in the region. Many caravans of Arabs and other merchants travelled west, ranging from the Sultanate of Shewa to Kaffa and Sidama kingdoms. In the late 10th century, the Makhzumite kingdom enlarged its territory on the periphery of Shewa, despite local Muslim opposition, while others established their kingdom towards the eastern escarpment of Shewa and the Harari plateau.[4]

As the Sultanate of Ifat was established in 1277, the Mukhzumite sultanate came to an end in 1285 after a defeat by the sultan of Quraysh, who annexed its territory. The kingdom also conquered the nearby Muslim states and trading principalities, and advanced to the eastern escarpment of Showa.[citation needed] Economic transitions caused the sultanate to extend its territory westward after a serious clash with Damot Christian and other local populations. The other Muslim polities (Dawaro, Fatagar, Bali, Sidamo and Hadiya kingdoms) consolidated in the south when the Sultanate of Ifat established hegemony. The Muslim confederation stretched southward to the Great Rift Valley lakes, and strong trading and cultural enrichment flourished until it was challenged by a Christian Solomonic dynasty from the north. Medieval Islam was introduced between the 12th and 13th century, influenced by Hamitic-Cushitic culture, and fundamentally altered by Ulama and impacted by the Hajj.[4]

Ethiopian Empire

Early Solomonic period to Zemene Mesafint

Historical regions such as Wag and Lasta were a watershed to the shift into an Ethiopian state.[1] In the 14th century, Emperor Amda Seyon (1314–1344) was able to expand the nation into the south of Shewa by encouraging the northern population in Gondar, Bulga, Menz, Beta Amhara, Angot, Gayint, Agaw Midre, Tigray and Jirru.[5] The expansion was widely considered religious and commercial but a few colonial motives also existed. Subsequent territorial expansion ushered in the formation and construction of new churches and monasteries in these Christian-inhabited areas and ample theocratical movement. As territorial expansion continued, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church became influential in colonization. The Ethiopian state generally extended between the rise of Yekuno Amlak and the death of Dawit II (Lebna Dengel) (1270–1540).[6] Medieval reports mentioned new settlers arriving in Kembatta during the reigns of Zara Yaqob and Amda Seyon I.[5]Around 1316/1317, Amda Seyon conquered Damot, creating trade routes through the Gibe and Omo basins. Now expansion of his realm was countered by southeast Muslim polities, the Walashma dynasty and the conquered Sultanate of Ifat.[4] In 1325, he established hegemony on the coast of Massawa and permeated Hadiya Sultanate in 1330, resulting in the subjugation of the Sidama principalities in the south. Amda Seyon overwhelmed the Muslim states in the east, including their trade routes, and annexed the Sultanate of Ifat in 1332. Although inconclusive, his victory concluded with the collapse of two Christian kingdoms in the west: the Dongola (Nubia) and Alwa (Sennar).[4]

After Zara Yacob's death, there ensued a brief decline of power. The nobility’s clashes aggravated the situation. Emperor Na'od was extremely intimidated and his weakened leadership gave the Adal Sultanate legitimacy in the region in 1415, with its capital in Dakkar (in present-day Somaliland).[4] The Adal rise to power resulted in a series of conflicts with the Ethiopian Empire, and eventually the Ethiopian–Adal War in 1529. Adal's general Ahmed ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmed Gran) quickly seized the Ethiopian Empire by conquering most of the Ethiopian Highlands, reaching northern Tigray Province in the Battle of Amba Sel in 1531. Dawit II then started a loosely organized resistance movement by mid-1530s. Slavery became the dominant market linking the Horn of Africa with the port of Zeila. The Abyssinians led by Emperor Gelawdewos, with the assistance of Portuguese musketeers, liberated the empire.[7]

Ethiopia was isolated and decentralized in a period known as Zemene Mesafint, starting with the rise of the Yejju Oromo dynasty after the Solomonic Emperor Iyoas I was deposed by the Tigray governor Ras Mikael Sehul on 7 May 1769. It was characterized by puppet monarchy, as Emperors became figureheads with minimal authority. In 1852, Kassa (Tewodros II) defeated Gojjam's force, and Ras Ali fled Gondar and with his army made for Debre Tabor. Tewedros ended Zemene Mesafint and united the Ethiopian principalities (Gojjam, Gondar and Shewa) after defeating them all in the Battle of Takusa in 1852, and proclaiming himself Emperor of Ethiopia in 1855. The Yejju's Ras Ali died in exile in 1856.[8]

Post-Zemene Mesafint wars

Beginning in 1874, an Ottoman-led Egyptian coalition invaded Ethiopia from three directions, penetrating through the port of Tajura in present-day Djibouti, but was repulsed by Aussa Sultanate. Harar was captured in 1875 and held until 1885 by Muhammad Rauf Pasha, but was defeated by an Ethiopian force at the Battle of Gundet. Again in 1876, an Egyptian force under American general Loring vainly attempted a second invasion and was defeated at the Battle of Gura. The Italian colony in 1885 took Egyptian-controlled Massawa, a port on the Red Sea, and declared it a protectorate. The aim was to compete with other European colonial powers and advance Ethiopian territory.[9] When the Italians expanded their conquests further inland, they were defeated by Mereb Mellash governor Ras Alula Engida at the Battle of Dogali in 1887.[10][unreliable source?]

The Dervish-led Mahdist Sudanese force fought Ethiopia; they were once defeated by Ras Alula to help the Egyptians in 1885, and finally won after the death of Emperor Yohannes IV in 1889 at the Battle of Gallabat.[10]

Menelik II

In 1896, Emperor Menelik II expanded his realm southward and formed the modern borders of Ethiopia, referred to as Menelik's Expansions. The expansion has two motives: the first was to save Ethiopia from European colonialism, and the second to acquire sufficient resources. A tripartite agreement was signed between Ethiopia, Britain and Italy on 24 March 1891 which demarcated the Juba River and Blue Nile.[11][12] The letter served as the basis of European interactions with and claims to the region of Ethiopia. Menelik’s expansion reached the area inhabited by numerous Oromo subgroups such as the Borena and the Arsi as well as the Somali territory of Ogaden. In 1889, he signed a treaty with Italian representatives to take over the Red Sea coast and some coastal highlands, which were later incorporated into an Italian colony in 1890.[9]

Menelik suffered food scarcity that made him unable to feed his armies or meet the needs of the highland populations and their livestock and plowing. By raiding southern lowland pastoralists, he successfully halted the widespread famine in the highlands and expanded his empire. According to Bahru Zewde (1978), surplus livestock was sent to Menelik, who divided it among his mekuanenet nobility. Meanwhile, refugees from the regions of Begemder and Tigray "ravaged the rank of conquering army".[13]

Insufficient food to meet requirements led the soldiers to additional seizures; Ras Wolde Gabriel mutilated, robbed and destroyed the Arsi population. Slavery and taxation were commonplace and the subjugated people were overtaxed more than their flocks increased yearly. In the late 19th century, the Ethiopian Empire attempted to invade and expand into southern Somalia by attacking two of its commercial towns such as Luuq and Baidoa but Menelik II forces were successfully defeated and driven back.[14] In 1897, Menelik’s armies conducted the final conquest against the Borena frontier, causing El Wak and Golbo tribes to mobilize on the Dirre plateau.[citation needed]

On 31 July 1897, 15,000 imperial soldiers led by Fitawrari Habte Giyorgis Dinagde subjugated Borena, and the first Ethiopian garrison was opened in Dirre and Liban with highly professional raiding parties in occupation. The British failure to be present in Borena led the Ethiopians quickly to the frontier to claim possession.[15] Borena's chieftain Qallu Afalata Dido heard the news of the conquest and dispatched a delegation to the British on the coast of Kismayu, through which, according to Hickey, he painted a "gloomy picture of Ethiopian predation". A boundary commission was sent in 1902–1903 to oversee and mark the border in line with 1897 Anglo-Ethiopian treaty, referred to as the Red Line.[16][17] On 10 July 1900, Italy signed a treaty with Ethiopia to demarcate the border between Ethiopia and the Italian colony of Eritrea.[18] The final delimitation formed from the border of Italian-occupied Somalia through the Italo-Ethiopian treaty of 1908 before French Somaliland, later Djibouti in March 1897, Italian Eritrea (1900, 1902, and 1908), British Kenya (December 1907), British Somaliland (1897 and 1907), and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (May 1902).[19]

Italian East Africa

After defeating the Ethiopian Army in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935, Italy proclaimed Ethiopia part of Italian East Africa in May 1936, consisting of the former colonies of Eritrea and Somaliland (occupied in 1940) covering over 666,000 square miles (1,725,000 square kilometres) with an estimated population of 12,100,000. However, the density of population was not even; Eritrea had an area of 99,000 square miles with 1,500,000 population, a density of 16.6 per square mile, Ethiopia with an area of 305,000 square miles, 9,450,000 population and 31.0 population density, and Somaliland with an area of 270,000, 1,150,000 population and 4.2 population density.[20] It was bordered at the time by Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in the west, British Somaliland in the east, British Kenya to the south and the Red Sea to the northeast.[21]

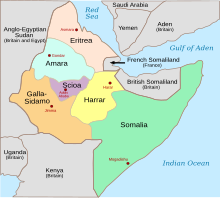

The Ethiopian Empire consisted of four administrative divisions: Harar, Galla-Sidamo, Amhara and Scioa Governorates, the latter enlarged in November 1938. The governorates were under the authority of an Italian governor, answerable to the Italian viceroy. During the Second World War on 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and France. In 1941, the British army and the Ethiopian Arbegnoch movement liberated Ethiopia in the East African Campaign, resulted in recognition of Ethiopia's sovereignty by the British under the 1944 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement, though some regions were briefly administered by the British, no more than 10 years. In 1947, Italy recognized Ethiopia's sovereignty, although various regions remained under British occupation for some years.

Federation with Eritrea

The British policy on Eritrea's status after Italy declared war on the Allies in 1940, was with the collaboration of Emperor Haile Selassie to help Eritrea to join Ethiopia. In early 1941, British and American consultants discussed the future handling of Tigray Province in Eritrea. Early in the war, communication with Eritrean soldiers was conducted with printed leaflets by an intelligence group led by George Steer. The primary objective was to disintegrate the Italian colonial army, and cause the Eritrean Askaris to desert. Steer succeeded: from November 1940 to February 1941, thousands of Eritrean Askaris deserted from the Italian army.[22]

In July 1940, an Ethiopian imperial decree was signed between Haile Selassie and Eritrean Minister of Foreign Affairs Lorenzo Taezaz, which addressed the admonition to struggle with "Ethiopian brothers". In May 1941, Eritrean leaders and elders formed "Mahber Fikiri Hager" (Association for the Love of Country), which functioned as what British described as the unionist and irredentist movement.[citation needed] Efforts to unite the colonial boundaries of Ethiopia followed the defeat of Italy in 1941. Two alternatives were discussed; handing Tigray territory over to Ethiopia and establishing Greater Somalia. The other side questioned Eritrean sovereignty in 1943.[22]

To assure the federative union of Ethiopia and Eritrea, the Unionist Party (UP) was established in Asmara on 5 May 1941, shortly after the Emperor returned to the throne after five years in exile. Demonstrations in Asmara declaimed the affinity between Ethiopia and Eritrea.[22] From 1943, the UP incorporated with the Separatist Movement, which sought to establish the ethnic, cultural and political unity of Tigreans residing in Eritrea, resulting in a resistance movement against the Haile Selassie administration known as the Woyane rebellion.

On 2 December 1950, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 390 to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia as "an autonomous unit...under the sovereignty of the Ethiopian Crown". The UN General Assembly also elected Anze Matienzo ad UN Commissioner for Eritrea in order to consult with BA,[clarification needed] the Ethiopian government and the Eritrean people to draft an Eritrean constitution, and assist the Eritrean Assembly to consider the constitution. Eritrea federated with Ethiopia on 1 September 1952.[23]

The lack of democracy in the empire incited upheaval in Eritrean society. For instance, an infringement on Eritrean judiciary body neglected the Eritrean Constitution as the supreme law of the land, and a drastic increase in tariffs in Eritrea with a 20% increase in the cost of living, led to a strike in October 1952, denouncing the economic hardship imposed on the population. On 30 September 1952, Proclamation number 30 issued by Haile Selassie, inciting a violation of Article 85 of the Eritrean Constitution. Formal opposition was generally repressed, citing corruption. However, resentment grew against the government of the Ethiopian Empire, and opposition was expressed primarily in song. In September 1960, a strike in Asmara demanded restoration of the Eritrean flag and seal, with 300–400 students participating. Protestors often were imprisoned; some were sent to Ethiopia to serve their prison terms. Eritrean resistance resurged by 1961, leading to the Eritrean War of Independence.[23]

Separation of Eritrea and Ethiopia

In 1991, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition who fought the Derg government during the Ethiopian Civil War, seized power over the Ethiopian government. A UN-monitored referendum was held in April 1993, with a majority of Eritreans favoring independence, and resulting in the recognition of an Eritrean government. On 28 May 1993, the new state of Eritrea was admitted to the United Nations.[24]

References

- ^ a b Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1-85065-393-6.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (2021-09-17). "The Kingdom of Aksum". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Hatke, George (2013-01-07). Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6283-7.

- ^ a b c d e Abir, Mordechai (2013-10-28). Ethiopia and the Red Sea: The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim European Rivalry in the Region. Routledge. pp. 22–70. ISBN 978-1-136-28090-0.

- ^ a b Zewde, Bahru; Pausewang, Siegfried (2002). Ethiopia: The Challenge of Democracy from Below. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 978-91-7106-501-8.

- ^ Fargher, Brian L. (1996). The Origins of the New Churches Movement in Southern Ethiopia: 1927 - 1944. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10661-1.

- ^ Salvadore, Matteo (2016-06-17). The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations, 1402-1555. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-04546-5.

- ^ Marcus, Harold G. (2002-02-22). A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92542-7.

- ^ a b Fuller, Mia (2007-01-24). Moderns Abroad: Architecture, Cities and Italian Imperialism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-64831-3.

- ^ a b Kassa, Taglo. Social Studies for Juniors. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-300-57084-4.

- ^ Lytton 1996, p. 23.

- ^ Hamilton 1974, p. 359.

- ^ Oba, Gufu (2013-07-11). Nomads in the Shadows of Empires: Contests, Conflicts and Legacies on the Southern Ethiopian-Northern Kenyan Frontier. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25522-7.

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ Hickey 1984, p. 119.

- ^ Huxley 1953, p. 39.

- ^ Oba 2013, p. 46.

- ^ Ofcansky, Thomas P.; Shinn, David H. (2004-03-29). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6566-2.

- ^ Berhe, Mulugeta Gebrehiwot (2020). Laying the Past to Rest: The EPRDF and the Challenges of Ethiopian State-building. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-78738-291-6.

- ^ E., D. P. (1940). "Italian Possessions in Africa: II. Italian East Africa". Bulletin of International News. 17 (17): 1065–1074. ISSN 2044-3986. JSTOR 25642850.

- ^ "Italian East Africa" (PDF). 8 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Negash, Tekeste (1997). Eritrea and Ethiopia: The Federal Experience. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 978-91-7106-406-6.

- ^ a b Iyob, Ruth (1997-05-13). The Eritrean Struggle for Independence: Domination, Resistance, Nationalism, 1941-1993. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59591-9.

- ^ Kohen, Marcelo G. (2006-03-30). Secession: International Law Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-139-45069-0.