Psychology of climate change denial

The psychology of climate change denial is the study of why people deny climate change, despite the scientific consensus on climate change. A study assessed public perception and action on climate change on grounds of belief systems, and identified seven psychological barriers affecting behavior that otherwise would facilitate mitigation, adaptation, and environmental stewardship: cognition, ideological worldviews, comparisons to key people, costs and momentum, disbelief in experts and authorities, perceived risks of change, and inadequate behavioral changes.[1][2] Other factors include distance in time, space, and influence.

Reactions to climate change may include anxiety, depression, despair, dissonance, uncertainty, insecurity, and distress, with one psychologist suggesting that "despair about our changing climate may get in the way of fixing it."[3] The American Psychological Association has urged psychologists and other social scientists to work on psychological barriers to taking action on climate change.[4] The immediacy of a growing number of extreme weather events are thought to motivate people to deal with climate change.[5]

Types of denial

Expanding the meaning of "denial"

The idea of "soft" or implicit climate change denial became prominent in the mid-2010s, but variations of the same concept originated earlier. An article published by National Center for Science Education referred to "implicit" denial:

Climate change denial is most conspicuous when it is explicit, as it is in controversies over climate education. The idea of implicit (or "implicatory") denial, however, is increasingly discussed among those who study the controversies over climate change. Implicit denial occurs when people who accept the scientific community's consensus on the answers to the central questions of climate change on the intellectual level fail to come to terms with it or to translate their acceptance into action. Such people are in denial, so to speak, about climate change.[6]

In May 2015, environmentalist Bill McKibben penned an op-ed criticizing Barack Obama's policies of approving petroleum exploration in the Arctic, expanding coal mining, and remaining indecisive on the Keystone XL pipeline. McKibben wrote:

This is not climate denial of the Republican sort, where people simply pretend the science isn't real. This is climate denial of the status quo sort, where people accept the science, and indeed make long speeches about the immorality of passing on a ruined world to our children. They just deny the meaning of the science, which is that we must keep carbon in the ground.[7]

McKibben's use of the word "denial" was an early expansion of the term's meaning in environmental discourse to include "denial of the significance or logical consequences of a fact or problem; in this case, what advocates see as the necessary policies that flow from the dangers of global warming."[8]

Analysis of soft climate change denial

Michael Hoexter, a scholar and sustainability advocate, analyzed the phenomenon of "soft climate change denial" in a September 2016 article for the blog New Economic Perspectives and expanded on the idea in a follow-up article published the next month.[9] Despite the term's earlier, informal usage, Hoexter has been credited with formally defining the concept.[10] In Hoexter's terms, "soft" climate denial "means that one acknowledges in some parts of one's life that climate change is real, disastrous and happening now but in most other parts of one's life, one ignores that anthropogenic global warming is, in fact, a real existential emergency and catastrophic."[11] According to Hoexter, "soft climate denial and the thin gruel of climate action policies that accompany it may be functioning as a 'face-saving' device to mask fundamental inertia or a deep manifest preference for inaction while continuing fossil-fueled business as usual."[12]

He also applied the term to "more 'radical' groups" that pushed for more responsive measures, but "often either miss the mark in terms of the climate challenge facing us or wrap themselves in communication strategies and 'memes' that limit their potential influence on politics and policy."[13] In Hoexter's view, soft denial can only be escaped through collective action, not individual action or realization.[14]

Soft climate change denial (also called implicit or implicatory climate change denial) is a state of mind acknowledging the existence of global warming in the abstract while remaining, to some extent, in partial psychological or intellectual denialism about its reality or impact. It is contrasted with conventional "hard" climate change denial, which refers to explicit disavowal of the consensus on global warming's existence, causes, or effects (including its effects on human society).

Psychological reasons for denial

Various psychological factors can impact the effectiveness of communication about climate change, driving potential climate change denial. Psychological barriers, such as emotions, opinions and morals refer to the internal beliefs that a person has which stop them from completing a certain action. Psychologist Robert Gifford wrote in 2011 "we are hindered by seven categories of psychological barriers, also known as dragons of inaction: limited cognition about the problem, ideological worldviews that tend to preclude pro-environmental attitudes and behavior, comparisons with other key people, sunk costs and behavioral momentum, discordance toward experts and authorities, perceived risk of change, and positive but inadequate behavior change".[2]

Distance in time, space, and influence

Climate change is often portrayed as occurring in the future, whether that be the near or distant future. Many estimations portray climate change effects as occurring by 2050 or 2100, which both seem much more distant in time than they really are, which can create a barrier to acceptance.[15] There is also a barrier created by the distance portrayed in climate change discussions.[15] Effects caused by climate change across the planet do not seem concrete to people living thousands of miles away, especially if they are not experiencing any effects.[15] Climate change is also a complex, abstract concept to many, which can create barriers to understanding.[15] Carbon dioxide is an invisible gas, and it causes changes in overall average global temperatures, both of which are difficult, if not impossible, for one single person to discern.[15] Due to these distances in time, space, and influence, climate change becomes a far-away, abstract issue that does not demand immediate attention.[15]

Anthony Leiserowitz, the director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication said that one "almost couldn't design a worse fit for our underlying psychology or our institutions of decision-making" than dealing with climate change—owing primarily to the short-term focus of humans and their institutions.[5]

Cognitive dissonance

.jpg/440px-Climate_March_0858_signs_(33571009024).jpg)

Because there is little solid action that people can take on a daily basis to combat climate change, then some believe climate change must not be as pressing an issue as it is made out to be.[15] An example of this phenomenon is that most people know smoking cigarettes is not healthy, yet people continue to smoke cigarettes, and so an inner discomfort is elicited by the contradiction in ‘thinking’ and ‘doing’.[15] A similar cognitive dissonance is created when people know that things like driving, flying, and eating meat are causing climate change, but the infrastructure is not in place to change those behaviors effectively.[15]

In order to address this dissonance, climate change is rejected or downplayed.[15] This dissonance also fuels denial, wherein people cannot find a solution to an anxiety-inducing problem, and so the problem is denied outright.[15] Creating stories that climate change is actually caused by something out of humans’ control, such as sunspots or natural weather patterns, or suggesting that we must wait until we are certain of all of the facts about climate change before any action be taken, are manifestations of this fear and consequent denial of climate change.[15]

"It seems as if people stop paying attention to global climate change when they realize that there are no easy solutions for it. Many people instead judge as serious only those problems for which they think action can be found."[15]

Individuals are alarmed about the dangerous potential futures resulting from a high-energy world in which climate change was occurring, but simultaneously create denial mechanisms to overcome the dissonance of knowing these futures, yet not wanting to change their convenient lifestyles.[16] These denial mechanisms include things like overestimating the costs of changing their lifestyles, blaming others, including government, rather than their own inaction, and emphasizing the doubt that individual action could make a difference within a problem so large.[16]

Cognitive barriers

Cognitive barriers to climate change acceptance include:

- Limited cognition of the human brain, caused by things like the fact that the human brain has not evolved much in thousands of years, and so has not transitioned to caring about the future rather than immediate danger,

- ignorance, the idea that environments are composed of more elements than humans can monitor, so we only attend to things causing immediate difficulty, which climate change does not seem to do

- uncertainty, undervaluing of distant or future risk, optimism bias,

- the belief that an individual can do nothing against climate change are all cognitive barriers to climate change acceptance.[2]

Conspiratorial beliefs

Climate change denial is commonly rooted in a phenomenon commonly known as conspiracy theory, in which people misattribute events to a secret plot or plan by a powerful group of individuals.[20] The development of conspiracy theories is further prompted by the proportionality bias that results from climate change — an event of mass scale and a great deal of significance — being frequently presented as a result of daily small-scale human behavior; often, individuals are less likely to believe large events of this scale can be so easily explained by ordinary details.[21]

This inclination is furthered by a variety of possible strong individually and socially grounded reasons to believe in these conspiracy theories. The social nature of being a human holds influential merit when it comes to information evaluation. Conspiracy theories reaffirm the idea that people are part of moral social groups that have the ability to remain firm in the face of deep-seated threats.[22][23] Conspiracy theories also feed into the human desire and motivation to maintain one's level of self-esteem, a concept known as self-enhancement.[24] With climate change in particular, one possibility for the popularity of climate change conspiracy theories is that these theories knee-cap the reasoning that humans are culpable for the degradation of their own world and environment.[25] This allows for maintenance of one's own self-esteem, and provides strong backing for belief in conspiracy theories. These climate change conspiracy theories pass the social blame to others, which upholds both the self and the in-group as moral and legitimate, making them highly appealing to those who perceive a threat to the esteem of themselves or their group.[26] In a similar vein, much like how conspiracy belief is linked with narcissism, it is also predicted by collective narcissism. Collective narcissism is a belief in the distinction of one's own group whilst believing that those outside the group do not give the group enough recognition.[27]

A variety of factors related to the nature of climate change science itself also enable the proliferation of conspiratorial beliefs. Climate change is a complicated field of science for lay people to make sense of. Research has experimentally indicated that people are used to creating patterns where there are none when they perceive a loss of control in order to return the world to one they can make sense of.[28] Research indicates that people hold stronger beliefs about conspiracies when they exhibit distress as a consequence of uncertainty, which are both prominent when it comes to climate change science.[29] Additionally, in order to meet the psychological desire for clear, cognitive closure, the likes of which is not consistently accessible to lay people regarding climate change, people often lean on conspiracy theories.[30] Bearing this in mind, it is also crucial to note that conspiracy belief is conversely lessened in intensity when individuals have their sense of control affirmed.[31]

People with certain cognitive tendencies are also more drawn to conspiracy theories about climate change as compared to others. Aside from narcissism as previously mentioned, conspiratorial beliefs are more predominantly found in those who consistently look for meanings or patterns in their world, which often includes those who believe in paranormal activities.[32] Climate change conspiracy disbelief is also linked with lower levels of education and analytic thinking.[33][34] If a person has a predisposed inclination towards perceiving others’ actions as having been actively done willfully even when no such thing is happening, they are more likely to buy into conspiratorial thinking.[34]

The global COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to the increase of conspiratorial beliefs, contested science, skepticism, and overall denial of climate science.[35] Researchers studying science skepticism of vaccination for COVID-19 see direct linkages between this and science skepticism for other large-scale domain issues like that of climate science.[35]

Threat to self-interest

The realisation that an individual's actions contribute to climate change can threaten their self-interest and compromise their psychological integrity.[36] The threat to self-interest can often result in ‘denialism’ – a refusal to accept and even deny the scientific evidence- manifested across all levels of society.[37] Large organisations that have a strong vested interest in activities directly responsible for climate change, such as fossil fuel companies, may even promote climate change denial through the spread of misinformation.[38][39]

Denial is manifested at the individual level where it is used to protect the self from overwhelming emotional responses to climate change.[40] This is often referred to as ‘soft denial’ or ‘disavowal’ in the relevant literature.[41] Here the dangers of climate change are experienced in a purely intellectual way, resulting in no psychological disturbance: cognition is split off from feeling. Disavowal can be induced by a wide variety of psychological processes including: the diffusion of responsibility, rationalisation, perceptual distortion, wishful thinking and projection.[42][43] These are all avoidant ways of coping.

Framing

In popular climate discourse framing, the three dominant framing ideas have been apocalypse, uncertainty and high costs/losses.[15] These framings create intense feelings of fear and doom and helplessness.[15][38] Framing climate change in these ways creates thoughts that nothing can be done to change the trajectory, that any solution will be too expensive and do too little, or that it is not worth trying to find a solution to something we are unsure is happening.[15] Climate change has been framed this way for years, and so these messages are instilled in peoples’ minds, elicited whenever the words "climate change" are brought up.[15]

Ideology and religion

Ideologies, including suprahuman powers, technosalvation, and system justification, are all psychological barriers to climate change acceptance.[2] Suprahuman powers describes the belief that humans cannot or should not interfere because they believe a religious deity will not turn on them or will do what it wants to do regardless of their intervention.[2] Technosalvation is the ideology that technologies such as geoengineering will save us from climate change, and so mitigation behavior is not necessary.[2] Another ideological barrier is the ideology of system justification, or the defense and justification of the status quo, so as to not "rock the boat" on a comfortable lifestyle.[2]

Own behaviors, habits, aspirations

People are also very invested in their own behavior. Behavioral momentum, or daily habits, are one of the most important barriers to remove for climate change mitigation.[2][47] Lastly, conflicting values, goals, and aspirations can interfere with the acceptance of climate change mitigation.[2] Because many of the goals held by individuals directly conflict with climate change mitigation strategies, climate change gets pushed to the bottom of their list of values, so as to minimize the extent of its conflict.[2]

One type of limited behavior is tokenism, where after completing one small task or engaging in one small behavior, the individual feels they have done their part to mitigate climate change, when in reality they could be doing much more.[2] Individuals could also experience the rebound effect, where one positive activity is diminished or erased by a subsequent activity (like walking to work all week because you are flying across the country every weekend).[2]

Financial investment in fossil fuels and other climate change inducing industries (sunk costs) is often a reason for denial of climate change.[47][2] If one accepts that these things cause climate change, they would have to lose their investment, and so continued denial is more acceptable.[47][37]

The difficulty of comprehending the sheer scale of global warming and its effects can result in sincere (albeit ill-founded) belief that individual changes in behavior will suffice to address the problem without requiring more fundamental structural changes.[48]

Views of others and perceived risk

If someone is held in a negative light, it is not likely others will take guidance from them due to feelings of mistrust, inadequacy, denial of their beliefs, and reactance against statements they believe threaten their freedom.[2]

Several types of perceived risk can occur when an individual is considering changing their behavior to accept and mitigate climate change: functional risk, physical risk, financial risk, social risk, psychological risk, and temporal risk.[2] Due to the perception of all of these risks, the individual may just reject climate change altogether to avoid potential risks completely.[2]

Social comparisons between individuals build social norms.[2] These social norms then dictate how someone "should" behave in order to align with society's ideas of "proper" behavior.[2][47] This barrier also includes perceived inequity, where an individual feels they should not or do not have to act a certain way because they believe no one else acts that way.[2][47]

Psychological reasons for soft denial

There are several beliefs or thought patterns that tend to contribute to soft climate denial:[13]

- Psychological isolation and compartmentalization – Events of everyday life usually lack an obvious connection to global warming. As such, people compartmentalize their awareness of global warming as abstract knowledge without taking any practical action. Hoexter identifies isolation/compartmentalization as the most common facet of soft denial.

- "Climate providentialism" – In post-industrial society, modern comforts and disconnection from nature lead to an assumption that the climate "will provide" for humans, regardless of drastic changes. Though named for a belief found in some forms of Christianity, Hoexter uses the term in a secular context and relates it to anthropocentrism.

- "Carbon gradualism" – An assumption that global warming can be addressed though minor "tweaks" conducted over extended periods of time. Proposals for more drastic change may be more realistic, but appear "radical" by comparison.

- Substitutionism – A tendency among politically engaged people to "substitute a high-minded pre-existing activist cause" in place of the more immediate challenge of fossil fuel phase-out. Hoexter associates substitutionism with eco-socialism, green anarchism, and the climate justice movement, which he said tends to prioritize "laudable and important concerns about environmental justice and inequality" at the expense of "the future-looking fight to stabilize the climate."

- Intellectualization – Engaging with climate change in a primarily academic context makes the issue an abstraction, lacking the visceral stimuli that prompt people to take concrete action.

- Localism – Emphasis on "small" changes to improve one's local environment is a well-intentioned but limited response to a problem on the scale of global warming.

- "Moral or intellectual narcissism" – Deriving a misplaced sense of superiority over "hard" climate deniers, soft deniers may come to believe that simply acknowledging the existence of climate change or expressing concern is sufficient by itself.

- "Confirmation of pre-existing worldview" – Because of cognitive inertia, people may fail to integrate the significance or scale of climate change the framework of their existing beliefs, knowledge, and priorities.

- Millenarianism – Activists become transfixed with a grand vision of an eventual, fundamental transformation of society, supplanting meaningful concrete action at the day-to-day level.

- Sectarianism – Activists may become preoccupied with a particular vision of climate policy and become caught up in the narcissism of small differences, tedious debates, and far-flung hypotheticals to the detriment of more productive activity.

- "Commitment to Hedonism" – The looming dread of climate change can emotionally overwhelm a person and may prompt a retreat into pleasure for its own sake.[47] Alternately, people may indulge in pleasurable activities that they worry may not be readily accessible in a future society adapted to climate change.

- "Entente with nihilism, defeatism, and depression" – In Hoexter's view, genuine nihilism remains a tendency within "hard" denialism; however, people who feel disempowered or overwhelmed about climate change may come to accept an uneasy coexistence with such nihilism.[37]

Examples

Soft climate denial has been ascribed to both liberals and conservatives, as well as proponents of market-based environmental policy instruments. It has also been used in self-criticism against tendencies toward complacency and inaction.[50] Depending on perspective, sources may differ on whether a person engages in "soft" or "hard" denial (or neither). For example, the environmental policy of the Trump administration has been described as both "soft" and "hard" climate denial.[51]

In Scientific American, Robert N. Proctor and Steve Lyons described Bret Stephens, a conservative New York Times opinion columnist and self-described "climate agnostic", as a soft denialist:[52]

The irony is that Stephens himself seems to presume that climate science must be understood in political terms—as part of a larger struggle between liberals and conservatives. But the reality of climate change has nothing to do with politics: it's an atmospheric fact, not a political fact. And the whole idea of needing to keep 'an open mind' to a legitimate 'controversy' is the very essence of modern 'soft' denialism.[52]

It was pointed out in 2017 that all the other current opinion columnists at the New York Times expressed varying degrees of soft denial in their work: "Like many liberals, every current liberal NYT columnist remains stuck in various states of 'soft' climate denial".[53] This applied to the writing of Stephens's fellow conservatives (Ross Douthat and David Brooks) as well as his liberal colleagues (Maureen Dowd, David Leonhardt, Frank Bruni, Gail Collins, Charles Blow, Paul Krugman, Nicholas Kristof, Thomas Friedman, and Roger Cohen).[53]

See also

- Anti-environmentalism

- Barriers to pro-environmental behavior

- Environmental skepticism

- False consciousness

- Fear, uncertainty, and doubt

- Individual action on climate change

- Inoculation theory

- Motivated reasoning

- Pluralistic ignorance

- Status quo bias

References

- ^ Lejano, Raul P. (16 September 2019). "Ideology and the Narrative of Climate Skepticism". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 100 (12): ES415–ES421. Bibcode:2019BAMS..100S.415L. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0327.1. ISSN 0003-0007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Gifford, Robert (2011). "The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation". American Psychologist. 66 (4): 290–302. doi:10.1037/a0023566. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 21553954. S2CID 8356816.

- ^ Green, Emily (13 October 2017). "The Existential Dread of Climate Change". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021.

- ^ Swim, Janet. "Psychology and Global Climate Change: Addressing a Multi-faceted Phenomenon and Set of Challenges. A Report by the American Psychological Association's Task Force on the Interface Between Psychology and Global Climate Change" (PDF). American Psychological Association. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b Hersher, Rebecca (4 January 2023). "How our perception of time shapes our approach to climate change". NPR. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023.

- ^ National Center for Science Education 2016.

- ^ McKibben 2015; quoted in Geman 2016.

- ^ Geman 2016.

- ^ Hoexter 2016a (the original article); Hoexter 2016b (the follow-up).

- ^ Rees & Filho 2018, p. 320 (crediting Hoexter as the originator of the concept).

- ^ Hoexter 2016a.

- ^ Hoexter 2016b; partially quoted in Rees & Filho 2018, p. 320.

- ^ a b Hoexter 2016b.

- ^ Rees & Filho 2018, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Stoknes, Per Espen (2014-03-01). "Rethinking climate communications and the "psychological climate paradox"". Energy Research & Social Science. 1: 161–170. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.007. hdl:11250/278817. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ a b Stoll-Kleemann, S.; O’Riordan, Tim; Jaeger, Carlo C. (July 2001). "The psychology of denial concerning climate mitigation measures: evidence from Swiss focus groups". Global Environmental Change. 11 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00061-3.

- ^ Barrett, Ted (February 27, 2015). "Inhofe brings snowball on Senate floor as evidence globe is not warming". CNN. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023.

- ^ "NASA, NOAA Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015". NASA. 20 January 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023.

- ^ Woolf, Nicky (26 February 2015). "Republican Senate environment chief uses snowball as prop in climate rant". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023.

- ^ McCauley, Clark; Jacques, Susan (May 1979). "The popularity of conspiracy theories of presidential assassination: A Bayesian analysis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37 (5): 637–644. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.5.637.

- ^ Leman, P.J.; Cinnirella, Marco (2007). "A major event has a major cause: Evidence for the role of heuristics in reasoning about conspiracy theories". Social Psychological Review. 9 (2): 18–28. doi:10.53841/bpsspr.2007.9.2.18. S2CID 245126866.

- ^ Tajfel, Henri; Turner, John C. (2004-01-09), "The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior", Political Psychology, Psychology Press, pp. 276–293, doi:10.4324/9780203505984-16, ISBN 978-0-203-50598-4, S2CID 49235478, retrieved 2021-05-09

- ^ Wohl, Michael J. A.; Branscombe, Nyla R.; Reysen, Stephen (2010-06-02). "Perceiving Your Group's Future to Be in Jeopardy: Extinction Threat Induces Collective Angst and the Desire to Strengthen the Ingroup". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 36 (7): 898–910. doi:10.1177/0146167210372505. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 20519571. S2CID 33363661.

- ^ Sedikides, Constantine; Gaertner, Lowell; Toguchi, Yoshiyasu (January 2003). "Pancultural self-enhancement". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 84 (1): 60–79. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.60. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 12518971.

- ^ Kunda, Ziva (1990). "The case for motivated reasoning". Psychological Bulletin. 108 (3): 480–498. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 2270237. S2CID 9703661.

- ^ Cichocka, Aleksandra; Marchlewska, Marta; Golec de Zavala, Agnieszka (2015-11-13). "Does Self-Love or Self-Hate Predict Conspiracy Beliefs? Narcissism, Self-Esteem, and the Endorsement of Conspiracy Theories". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 7 (2): 157–166. doi:10.1177/1948550615616170. hdl:10071/11366. ISSN 1948-5506. S2CID 146661388.

- ^ Cichocka, Aleksandra; Marchlewska, Marta; Golec de Zavala, Agnieszka; Olechowski, Mateusz (2015-10-28). "'They will not control us': Ingroup positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies". British Journal of Psychology. 107 (3): 556–576. doi:10.1111/bjop.12158. hdl:10071/12230. ISSN 0007-1269. PMID 26511288. S2CID 25101456.

- ^ Whitson, J. A.; Galinsky, A. D. (2008-10-03). "Lacking Control Increases Illusory Pattern Perception". Science. 322 (5898): 115–117. Bibcode:2008Sci...322..115W. doi:10.1126/science.1159845. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18832647. S2CID 1593413.

- ^ van Prooijen, Jan-Willem; Jostmann, Nils B. (2012-12-17). "Belief in conspiracy theories: The influence of uncertainty and perceived morality". European Journal of Social Psychology. 43 (1): 109–115. doi:10.1002/ejsp.1922. ISSN 0046-2772.

- ^ Marchlewska, Marta; Cichocka, Aleksandra; Kossowska, Małgorzata (2017-11-11). "Addicted to answers: Need for cognitive closure and the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs". European Journal of Social Psychology. 48 (2): 109–117. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2308. ISSN 0046-2772.

- ^ van Prooijen, Jan-Willem; Acker, Michele (2015-08-10). "The Influence of Control on Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Conceptual and Applied Extensions". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 29 (5): 753–761. doi:10.1002/acp.3161. ISSN 0888-4080.

- ^ Bruder, Martin; Haffke, Peter; Neave, Nick; Nouripanah, Nina; Imhoff, Roland (2013). "Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories Across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 225. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 3639408. PMID 23641227.

- ^ Swami, Viren; Voracek, Martin; Stieger, Stefan; Tran, Ulrich S.; Furnham, Adrian (December 2014). "Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories". Cognition. 133 (3): 572–585. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 25217762. S2CID 15915194.

- ^ a b Douglas, Karen M.; Sutton, Robbie M.; Callan, Mitchell J.; Dawtry, Rael J.; Harvey, Annelie J. (2015-08-18). "Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories". Thinking & Reasoning. 22 (1): 57–77. doi:10.1080/13546783.2015.1051586. ISSN 1354-6783. S2CID 146892686.

- ^ a b Rutjens, Bastiaan T.; van der Linden, Sander; van der Lee, Romy (February 2021). "Science skepticism in times of COVID-19". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 24 (2): 276–283. doi:10.1177/1368430220981415. hdl:1871.1/cffabf10-548b-46a8-9d27-dc5cb2f2b4d6. ISSN 1368-4302. S2CID 232132760.

- ^ Herranen, Olli (June 2023). "Understanding and overcoming climate obstruction". Nature Climate Change. 13 (6): 500–501. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13..500H. doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01685-6. S2CID 259114477.

- ^ a b c Mortillaro, Nicole (December 2, 2018). "The psychology of climate change: Why people deny the evidence". CBC News. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Hall, David (October 8, 2019). "Climate explained: why some people still think climate change isn't real". The Conversation. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ Oreskes, Naomi; Conway, Erik M. (2010). "Defeating the merchants of doubt". Nature. 465 (7299): 686–687. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..686O. doi:10.1038/465686a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20535183. S2CID 4414326.

- ^ Jylhä, K. M.; Stanley, S. K.; Ojala, M.; Clarke, E. J. R (2023). "Science Denial: A Narrative Review and Recommendations for Future Research and Practice". European Psychologist. 28 (3): 151–161. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000487. S2CID 254665552.

- ^ Weintrobe, Sally (2019-09-05), "The Climate Crisis", Routledge Handbook of Psychoanalytic Political Theory, Routledge, pp. 417–428, doi:10.4324/9781315524771-34, ISBN 978-1-315-52477-1, S2CID 210572297, retrieved 2020-09-18

- ^ Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in denial: Climate change, emotions, and everyday life. mit Press.

- ^ Hoggett, Paul (2019-06-01). Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster. Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-11741-2.

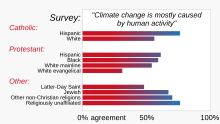

- ^ Contreras, Russell; Freedman, Andrew (4 October 2023). "Survey: Religion and race shape views on cause of climate change". Axios. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Axios credits "Data: PRRI" (Public Religion Research Institute).

- ^ Sparkman, Gregg; Geiger, Nathan; Weber, Elke U. (23 August 2022). "Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 4779. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.4779S. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-32412-y. PMC 9399177. PMID 35999211.

- ^ Yoder, Kate (29 August 2022). "Americans are convinced climate action is unpopular. They're very, very wrong. / Support for climate policies is double what most people think, a new study found". Grist. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Steg, Linda (January 2023). "Psychology of Climate Change". Annual Review of Psychology. 74: 391–421. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-032720-042905. PMID 36108263. S2CID 252310788.

- ^ Pasek 2019, p. 6.

- ^ Igielnik, Kim Parker, Nikki Graf and Ruth (2019-01-17). "Generation Z Looks a Lot Like Millennials on Key Social and Political Issues". Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Read 2019, p. 93.

- ^ Sources describing Trump as a "hard" denialist:

- Read 2019, pp. 92–93

- Resnikoff 2017 ("On the first round of Sunday shows since President Donald Trump announced the United States' withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, two members of his cabinet [Scott Pruitt and Nikki Haley] defended the move by promulgating a form of soft climate denialism.")

- ^ a b Proctor & Lyons 2017.

- ^ a b Siddique 2017.

Sources

- Anon. (January 15, 2016). "Why Is It Called Denial?". National Center for Science Education. Archived from the original on November 22, 2019.

- Geman, Ben (April 7, 2016). "Are President Obama and Hillary Clinton in Climate-Change 'Denial'?". National Journal. Atlantic Media. (subscription required)

- Hoexter, Michael (September 7, 2016). "Living in the Web of Soft Climate Denial". New Economic Perspectives. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019.

- ——— (October 6, 2016). "A Pocket Handbook of Soft Climate Denial". New Economic Perspectives. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019.

- McKibben, Bill (May 12, 2015). "Obama's Catastrophic Climate-Change Denial". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015.

- Pasek, Anne (October 11, 2019). "Mediating Climate, Mediating Scale". Humanities. 8 (4): 159. doi:10.3390/h8040159.

- Proctor, Robert; Lyons, Steve (May 8, 2017). "Soft Climate Denial at The New York Times". Scientific American. Springer Nature. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019.

- Read, Rupert (July 8, 2019). "What Is New in Our Time: The Truth in 'Post-Truth' – A Response to Finlayson" (PDF). Nordic Wittgenstein Review (Special Issue: Post–Truth): 81–96. doi:10.15845/nwr.v8i0.3507 – via NordicWittgensteinReview.com

.

. - Rees, Morien; Filho, Walter Leal (2018). "Feeling the Heat: The Challenge of Communicating 'High-End' Climate Change". In Filho, Walter Leal; Manolas, Evangelos; Azul, Anabela Marisa; Azeiteiro, Ulisses M.; McGhie, Henry (eds.). Handbook of Climate Change Communication: Vol. 1. Climate Change Management. Springer International Publishing. pp. 319–328. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69838-0_20. ISBN 978-3-319-69838-0 – via Google Books.

- Resnikoff, Ned (June 4, 2017). "Trump cabinet officials propagate soft climate denial on the Sunday shows". ThinkProgress. Center for American Progress. Archived from the original on September 7, 2019.

- Siddique, Ashik (May 16, 2017). "Cognitive Dissonance on Climate". Resilience.org. Post Carbon Institute. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019.