Siege of Songping

| Siege of Songping (863) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Tang-Nanzhao war in Annan | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Nanzhao | Tang dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Duan Qiuqian Yang Sijin Chu Đạo Cổ | Cai Xi † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 50,000 | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

Location of the battle | |||||||

| History of Hanoi |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The siege of Songping or the siege of Hanoi was the pivotal part of Nanzhao's great offensive in 863. Nanzhao was in alliance with local tribal rebels, against the Tang dynasty who was currently in control of the Red River Delta in modern-day northern Vietnam. The siege took place in Songping (modern-day Hanoi), capital of Tang's frontier Protectorate General to Pacify the South in early 863 during the reign of Emperor Yizong. It was the fourth time since 858 that Songping was attacked by Nanzhao forces

The siege was one of the most important and tragic events in the history of Vietnam before the tenth century. With 50,000 men from its main army and other tribal mercenaries combined, the Yunnanese approached Songping and issued an ultimatum to surrender or die. They laid siege on the city from mid-January until its fall on 1 March, resulting in military disaster and the retreat of Tang forces out of the region in 2 years.

Background

Nanzhao was a powerful kingdom to the southwest of the Tang dynasty. With their mighty military, Nanzhao rapidly expanded their empire in every direction, defeating a Tang invasion in 751,[1] joining with the Tang and defeating the Tibetans in 801,[2] decimating Pyu city-states in 832, subduing the Michen kingdom (near Ayeyarwady River) in the 830s. Nanzhao first raided the Tang frontier province of Annan in 846. Nanzhao then offered peace to the Tang, but in 854 the Tang suspended relations with Nanzhao and refused to receive its tribute.[3]

The Annan Protectorate (now northern Vietnam), with its capital city of Songping, was a center of commerce on the Maritime Silk Road and a rice basket of the Tang dynasty at the time. When Li Zhuo became jiedushi of Annan in 854, he reduced the amount of salt traded to the Chongmo Man in Fengzhou (modern-day Phú Thọ and Hòa Bình Province) in the west in exchange for horses. The mountains chiefs responded by launching raids on Chinese garrisons.[4] When Li Zhuo began suffering defeats, Đỗ Tồn Thành, a military commander, allied himself with the tribal chiefs against Li.[4] In the next year, Li Zhuo killed Đỗ Tồn Thành as well as the chieftain of the Qidong Man in Aizhou (Nghệ An, central Vietnam).[5] The Đỗ tribe had been a powerful Viet family in Thanh Hoá and Nghệ An since the 5-6th century. These actions provoked the natives into an alliance with Nanzhao. Fan Chuo, a Tang official in Annan reported: "…The native chiefs within the frontiers were subsequently seduced by the Man rebels…"[5] and "again became close friends with them. As days passed and months came, we gradually had to encounter raids and sudden attacks. This caused a number of places to fall into rebel hands."[5]

In modern-day Phú Thọ and Hòa Bình Province on the western frontier of the protectorate, the local general Lý Do Độc who led an army of 6,000, and was assisted by seven commanders called "Lords of the Ravines", submitted to Nanzhao.[4] The Nanzhao king Meng Shilong (蒙世隆) sent a Trustee of the East to deliver a letter to Do Độc soliciting his submission. Lý Do Độc and the Lords of the Ravine accepted the offer of vassalage by the Nanzhao king, who sent the Trustee one of his daughters to marry Lý Do Độc's eldest son. In 858, Nanzhao dispatched military forces to the region. In the meantime, local chiefs led raids that brought warfare to villages in the heart of the protectorate.[6]

In 857, Song Ya was sent to Annan to deal with the situation, but was recalled to deal with another rebellion after only two months. His replacement, Li Hongfu, only had nominal control over the protectorate, which was actually controlled by La Hanh Cung, who commanded 2,000 well trained soldiers. By 858, the Nanzhao army had joined with Lý Do Độc's force and raided Annan's capital Songping.[7] In 858, the Tang court sent a new jiedushi, Wang Shi, to protect Annan. He banished La Hanh Cung, saw off a Nanzhao reconnaissance force, and defeated an invasion by the mountain tribes. The Tang garrisons were upgraded with heavy-armored cavalry and infantry and Songping was fortified with a reed palisade. In the same year, a serious rebellion broke out in Yongzhou. The situation in Yongzhou threatened land communication between Annan and the empire, so a special army was established there to deal with rebels and to insure communications. This army was called the Yellow Head Army, for the soldiers wore yellow bands around their heads. In early autumn, local people were agitated by a rumor that the Yellow Head Army had embarked to attack them by surprise. One evening they surrounded Songping and demanded that Wang Shi return north and allow them to fortify the city against the Yellow Head Army. Shi was eating his evening meal when this commotion broke out. It is reported that, paying no heed to the mutineers, he leisurely finished his meal. Then, dressed in his battle gear, he appeared on the wall with his generals and admonished the crowd of rebels, who dispersed. The next morning, Shi's troops captured and beheaded some ringleaders of the affair.[8]

In 860, Wang Shi was recalled to deal with a rebellion elsewhere. The new jiedushi, Li Hu, arrived at Songping and executed Đỗ Tồn Thành's son, Đỗ Thủ Trừng, who according to Chinese sources was involved in a mutiny years earlier, probably due to the death of his father at the hands of Li Zhuo four years earlier. This alienated many of the powerful local clans of Annan.[9] Anti-Tang Viets allied with highland people, who appealed to Nanzhao for help, and as a result invaded the area in 860, briefly taking Songping before being driven out by a Tang army the next year.[5][10] Prior to Li Hu's arrival, Nanzhao had already seized Bozhou. When Li Hu led an army to retake Bozhou, the Đỗ family gathered 30,000 men, including contingents from Nanzhao to attack the Tang.[9] When Li Hu returned, he learned that Annan had been lost to Đỗ. On 17 January 861, Songping fell and Li Hu fled to Yongzhou.[9] Li Hu retook Songping[11] on 21 July but Nanzhao's forces moved around and seized Yongzhou. Li Hu was banished to Hainan island and was replaced by Wang Kuan.[12][9] Wang Kuan and the Tang court sought local cooperation by recognizing the power of the Đỗ family, granting a posthumous title to Đỗ Tồn Thành along with an apology for the deaths of him and his son and an admission that Li Hu had exceeded his authority.[9]

A relief army of 30,000 men was sent to Songping but soon left the city when rivalry broke out between Cai Xi, the military governor, and Cai Jing, an administrative and military official of Lingnan.[11] Cai Xi was then left responsible for holding Songping against an imminent Nanzhao offensive.[13] The city was surrounded by 4 miles (6,344 meters) of moated rampart–some parts seven to eight meters high. East of the city was the Red River.[14] Much of the information about the battle was written by Fan Chuo, a Tang official who wrote an eyewitness account about the southern barbarians (people of Annan and Yunnan) during the siege.[15]

Siege

.jpg/440px-Kingdom_of_Dali_Buddhist_Volume_of_Paintings_(51169310314).jpg)

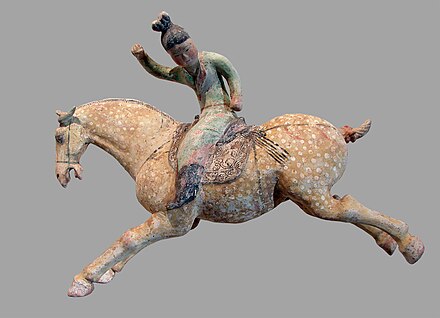

In mid-January of 863, Nanzhao returned with an invasion force numbering 50,000 led by Duan Qiuqian and Yang Sijin and besieged Annan's capital Songping.[16][17] Nanzhao's army included an assortment of Man tribes. There were 5–6,000 local Taohua forces, 2–3,000 Mang Man from west of the Mekong River who wore blue trousers and canes and strips of bamboo on their waists, Luoxing Man who wore no clothes except tree bark, He Man from the borderlands, Xunjuan Man who went barefoot but could tread on brambles and thorns and wore wicker helmets, and Wangjuzi Man whose menfolk and womenfolk alike were nimble and good with the lance on horseback.[18]

On 20 January, the defenders led by Cai Xi killed a hundred of the besiegers. Five days later, Cai Xi captured, tortured, and killed a group of enemies known as the Puzi Man. A local official named Liang Ke (V. Lương Cảo, belonged to the Puzi tribe) who was related to them recognized their dead bodies by their distinctive helmets and belts unique to each tribe, and defected. The troops of the Jiangxi General took the corpses of the besiegers and broiled them.[13] He defected.[19]

On 28 January, a naked Buddhist monk, possibly Indian, was wounded in the breast by an arrow shot by Cai Xi while strutting to and fro outside the southern walls. He was carried back to the camp by lots of Man. On 14 February, Cai Xi shot down 200 of the Wangjuzi and over 30 horses using a mounted crossbow from the walls. By 28 February, most of Cai Xi's followers had perished, and he himself had been wounded several times by arrows and stones. The enemy commander, Yang Sijin, penetrated the inner city. Cai Xi tried to escape by boat, but it capsized midstream, drowning him.[19][20] Fan Chuo escaped east via the Red River.[21] The 400 remaining defenders wanted to flee as well, but could not find any boats, so they chose to make a last stand at the eastern gate. Ambushing a group of enemy cavalry, they killed over 2,000 enemy troops and 300 horses before Yang sent reinforcements from the inner city.[19]

Aftermath

After taking Songping, on 20 June Nanzhao laid siege to Junzhou (modern Haiphong). A Nanzhao and rebel fleet of 4,000 men led by a chieftain named Chu Đạo Cổ (Zhu Daogu, 朱道古) was attacked by a local commander, who rammed their vessels and sank 30 boats, drowning them. In total, the invasion destroyed Chinese armies in Annan numbering over 150,000.[22] Although initially welcomed by the local Viets in ousting Tang control, Nanzhao turned on them, ravaging the local population and countryside. Both Chinese and Vietnamese sources note that the Viets fled to the mountains to avoid destruction.[17] A government-in-exile for the protectorate was established in Haimen (near modern-day Hạ Long) with Song Rong in charge. Ten thousand soldiers from Shandong and all other armies of the empire were called and concentrated at Halong Bay for reconquering Annan. A supply fleet of 1,000 ships from Fujian was organized.[23] Nanzhao and its allies launched another siege on Yongzhou (Nanning, Guangxi) in 864, but was repelled.[24]

The Tang launched a counterattack in 864 under Gao Pian, a general who had made his reputation fighting the Türks and the Tanguts in the north, with 5,000 troops and experienced initial success against Nanzhao, however political machinations at court led to Gao Pian's recall. In September 865, Gao Pian's forces surprised a Nanzhao army of 50,000 when they were collecting rice from the villages. Gao captured large quantities of rice, which he used to feed his army.[23][25] In the meantime, Gao had been reinforced by 7,000 men who arrived overland under the command of Wei Zhongzai.[26] In early 866, Gao Pian's 12,000 men defeated a fresh Nanzhao army and chased them back to the mountains. After his recall, he was later reinstated and completed the retaking of Songping in fall 866, executing the enemy general, Duan Qiuqian, and beheading 30,000 of his men.[24] Gao Pian renamed Annan to Jinghai Jun (lit. Peaceful Sea Army).[27][28] More than half of local rebels fled into the mountains.[29]

Nanzhao's 863 victory was so crucial to the Tang that some later Chinese scholars, for example, Song Qi, co-author of the New Book of Tang traced the root of the Tang dynasty's collapse to the recruitment of dissatisfied peasant-soldiers to Annan, who later joined the Huang Chao rebellion which decimated the Tang dynasty in the 880s.[30]

References

Citations

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 107.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1983, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d Kiernan 2019, p. 118.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 241.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 241-242.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor 1983, p. 243.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 42.

- ^ a b Wang 2013, p. 123.

- ^ Herman 2007, p. 36.

- ^ a b Kiernan (2019), p. 120.

- ^ Purton (2009), p. 106.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 115.

- ^ Schafer 1967, p. 67.

- ^ a b Taylor 1983, p. 244.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 120-121.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1983, p. 245.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 121.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 122.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 123.

- ^ a b Taylor 1983, p. 246.

- ^ a b Schafer 1967, p. 68.

- ^ Wang (2013), p. 124.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 247.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 120-123.

- ^ Xiong 2009, p. cxiv.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 248.

- ^ Yang (2008), p. 65–66.

Works cited

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-05379-6.

- Purton, Peter Fraser (2009). A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 450-1220. Boydell & Brewer.

- Schafer, Edward Hetzel (1967), The Vermilion Bird: T'ang Images of the South, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-01145-8

- Taylor, K.W. (1983), The Birth of the Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0

- Taylor, K.W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0

- Wang, Zhenping (2013). Tang China in Multipolar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War. University of Hawaii Press.

- Yang, Yuqing (2008). The Role of Nanzhao history in the Formation of Bai identity. University of Oregon.

Primary account

- Fan, Chuo (1961). The Man Shu: Book of the Southern Barbarians (863, translated 1961). Southeast Asia Program, Department of Far Eastern Studies, Cornell University.