Pre-colonial Timor

| History of East Timor |

|---|

|

| Chronology |

| Topics |

|

|

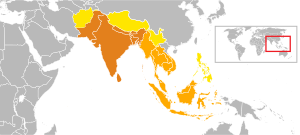

Timor is an island in South East Asia. Geologically considered a continental crustal fragment, it lies alongside the Sunda shelf, and is the largest in a cluster of islands between Java and New Guinea.[1] European colonialism has shaped Timorese history since 1515, a period when it was divided between the Dutch in the west of the island (now Indonesian West Timor) and the Portuguese in the east (now the independent state of East Timor).

Early history

The island of Timor was populated as part of the human migrations that have shaped Australasia more generally. It is believed that survivors from three waves of migration still live in the country. The first is described by anthropologists as Vedda people who arrived from the north and west at least 42,000 years ago.[citation needed] In 2011 evidence was uncovered, at the Jerimalai cave site, showing that these early settlers had high-level maritime skills at this time, and by implication the technology needed to make ocean crossings to reach Australia and other islands, as they were catching and consuming large numbers of big deep sea fish such as tuna.[2] These excavations also discovered one of the world's earliest recorded fish hooks, between 16,000 and 23,000 years old.[3]

Around 3000 BC, a second migration brought Melanesians. The earlier Vedda peoples withdrew at this time to the mountainous interior. Finally, proto-Malays from 2500 BC arrived from south China and north Indochina.[4] Timorese origin myths tell of ancestors that sailed around the eastern end of Timor arriving on land in the south. Some stories recount Timorese ancestors journeying from the Malay Peninsula or the Minangkabau Highlands of Sumatra.[5]

The Timorese in their region

The later Timorese were not seafarers, rather they were land focused peoples who did not make contact with other islands and peoples by sea. Timor was part of a region of small islands with small populations of similarly land-focused peoples that now make up eastern Indonesia. Contact with the outside world was via networks of foreign seafaring traders from as far as China and India that served the archipelago. Outside products brought to the region included metal goods, rice, fine textiles, and coins exchanged for local spices, sandalwood, deer horn, bees' wax, and slaves.[5]

Indianised Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms (3rd century – 16th century)

Earlier Buddhist era (3rd century BCE – 7th century)

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Indianised Javanese Hindu-Buddhist Srivijaya empire (7th – 12th century)

Oral traditions of people of the Wehali principality of East Timor mention their migration from Sina Mutin Malaka or "Chinese White Malacca" (part of Indianised Hindu-Buddhist Srivijaya empire) in ancient times.[7]

Relations with Indianised Javanese Hindu empire of Majapahit (12th – 16th century)

Majapahit empire's Nagarakretagama chronicles called Timor a tributary,[8] but as Portuguese chronologist Tomé Pires wrote in the sixteenth century, all islands east of Java were called "Timor".[9] Indonesian nationalist used the Majapahit chronicles to claim East Timor as part of Indonesia.[10]

Chiefdoms or polities

Early European explorers report that the island had a number of small chiefdoms or princedoms in the early sixteenth century. One of the most significant is the Wehali or Wehale kingdom in central Timor, to which the Tetum, Bunak and Kemak ethnic groups were aligned.[11]

The account of Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan expedition, who visited Timor in 1522, confirms the importance of the Wewiku-Wehali kingdom. In the seventeenth century the ruler of Wehali was described as "an emperor, whom all the kings on the island adhere to with tribute, as being their sovereign".[12] He entertained friendly contacts with the Muslim kingdom of Makassar, but his power was checked by devastating invasions by the Portuguese in 1642 and 1665.[13] Wehali was now brought inside the Portuguese sphere of power but appears to have had limited contact with its colonial suzerain.

Trade with China

Timor is mentioned in the thirteenth-century Chinese Zhu Fan Zhi, where it is called Ti-wu and is noted for its sandalwood. It is called Ti-men in the History of Song of 1345. Writing towards 1350, Wang Dayuan refers to a Ku-li Ti-men, which is a corruption of Giri Timor, meaning island of Timor.[14] Giri from "mountain" in Sanskrit, thus "mountainous island of Timor".

Trade with the Philippines

Filipinos, known as Luções among Portuguese sailors, were recorded to have visited and settled in East Timor before Spanish colonization of the Philippines. The Magellan expedition recorded that when they anchored on the island, they witnessed Luções merchants who traded Philippine gold for East Timorese sandalwood.[15]

European colonisation and Christianisation (16th century onward)

Beginning in the early sixteenth century, European colonialists—the Dutch in the island's west, and Portuguese in the east—would divide the island, isolating the East Timorese from the histories of the surrounding archipelago.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Monk, K.A.; Fretes, Y.; Reksodiharjo-Lilley, G. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. pp. 41–43. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

- ^ "Evidence of 42,000 year old deep sea fishing revealed : Archaeology News from Past Horizons". Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ O'Connor, S.; Ono, R.; Clarkson, C. (24 November 2011). "Pelagic Fishing at 42,000 Years Before the Present and the Maritime Skills of Modern Humans". Science. 334 (6059): 1117–1121. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1117O. doi:10.1126/science.1207703. hdl:1885/35424. PMID 22116883.

- ^ Timor Leste History Archived 9 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, official website.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 378. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar, 1933– (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- ^ H.J. Grijzen (1904), 'Mededeelingen omtrent Beloe of Midden-Timor', Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap 54, pp. 18–25.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 377. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- ^ Population Settlements in East Timor and Indonesia Archived 2 February 1999 at the Wayback Machine – University of Coimbra

- ^ History of Timor Archived 24 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Technical University Lisbon (PDF-Datei; 805 kB)

- ^ Precolonial East Timor.

- ^ L. de Santa Catharina (1866), História de S. Domingos, Quatra parte. Lisboa: Panorama, p. 300.

- ^ James J. Fox (1982), 'The great lord rests at the centre: The paradox of powerlessness in European-Timorese relations, Canberra Anthropology 5:2, p. 22.

- ^ Ptak, Roderich (1983). "Some References to Timor in Old Chinese Records". Ming Studies. 1: 37–48. doi:10.1179/014703783788755502.

- ^ The Mediterranean Connection By William Henry Scott (Published in "Philippine Studies" ran by Ateneo de Manila University Press)