Post-Mauryan coinage

Post-Mauryan coinage refers to the period of coinage production in India, following the breakup of the Maurya Empire (321–185 BCE).

The centralized Mauryan power ended during a Coup d'état in 185 BCE leading to the foundation of the Shunga Empire. The vast and centralized Maurya Empire was broken into numerous new polities. In the east, the newly formed Sunga Empire utilized the industries pre-established in Pataliputra.

Yona kings, which were once incorporated by or allied with the Mauryan Empire, settled in the Indus forming Indo-Greek Kingdoms bringing new coinage practices.[2] These techniques were utilized by the Indo-Scythian Kingdoms and Kushan Empire.

In the south the Satavahana Empire appeared, all with their specific coinage. The unified coinage, made of punch-marked coins, also broke up. In the northwest, several small independent entities were formed, which started to strike their own coins.

Technology

Punch-marked coinage

These political changes were accompanied by technological changes in coin production techniques. Before the collapse of the Maurya Empire, the main type of coinage was punch-marked coins. After manufacturing a sheet of silver or silver alloys, coins were cut out to the proper weight, and then impressed by small punch-dies. Typically from 5 to 10 punch dies could be impressed on one coin.[3] Punch-marked coins continued to be used for about three more centuries in the south, but in the north they disappeared in favour of the production of cast-die coinage.[4]

Cast die-struck coinage

The types of coins were replaced at the fall of the Maurya Empire by cast, die-struck coins.[5] Each individual coins was first cast by pouring a molten metal, usually copper or silver, into a cavity formed by two molds. These were then usually die-struck while still hot, first on just one side, and then on the two sides at a later period. The coin devices are Indian, but it is thought that this coin technology was introduced from the West, possibly from the neighboring Greco-Bactrian kingdom.

Northwestern cast die-struck coinage

Single-die coins

The most ancient of the coins are those that were die-cast on one side only, the other side remaining blank.[3] They seem to start as early 220 BCE, that is, already in the last decades of the Maurya Empire.[6] Some of these coins were created before the Indo-Greek invasions (dated to circa 185 BCE, start of the Yavana era), while most of the others were created later. These coins incorporate a number of symbols, in a way which is very reminiscent of the previous punch-marked coins, except that this time the technology used was cast single die-struck coinage.[7]

Single-die coins (220-185 BCE)

| Single-die coins before Indo-Greek invasions (220-185 BCE) |

|

Single-die coins after the Greco-Bactrian invasions (185 BCE)

The year 185 BCE is the approximate date the Greco-Bactrians invaded India. This date marks an evolution in the design of single-die cast coins, as deities and realistic animals were introduced.[7] At the same time coinage technology also evolved, as double-die coins (engraved on both sides, obverse and reverse) started to appear.[7] The archaeological excavations of coins have shown that these coins, as well as the new double die coins, were contemporary with those of the Indo-Greeks.[7]

| Single-die coinage after the Indo-Greek invasions (185 BCE) |

|

Double-die coins (185 BCE onward)

Progressively, after 185 BCE and the Greek invasion, coins were cast on both sides.[3] These coins are generally anonymous, and can carry Brahmi or Kharoshthi legends. These coins have quite specific types, depending mainly on the region where they were struck. Coins with a lion device are mainly known from Taxila, while coins with other symbols such as the Swastika or the Bodhi tree are attributed to the region of Gandhara.[3] These coins were cast during the rule of Indo-Greek kings Pantaleon and Agathocles in the area of Gandhara, and they are generally contemporary with those of Indo-Greek rulers.[7][9]

Main designs

| Main designs |

|

Later, humped or elephant images are known from Ayodhya, Kausambi, Panchala and Mathura. The coins of Ayodhia generally have a humped bull on the reverse, while the coins of Kausambi display a tree with railing.[3]

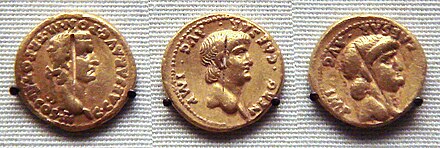

Indian-standard coinage of the Greeks (185 BCE onward)

The Indo-Greeks, following their invasion of the Indian subcontinent circa 185 BCE, in turn started to mint their own coins in the Indian standard (Indian weight, square shape, and less often round shape) with bilingual inscriptions, from the reign of Agathocles (190-180 BCE).

Symbolism

In addition to their own Attic coins, Greek kings thus started to issue bilingual Greek-Prakrit coins in the Indian standard, often taking over numerous symbols of the Post-Mauryan Gandhara coins, such as the arched-hill symbol and the tree-in-railing or Goddess Lakshmi at the beginning, and depictions of the bull and elephant later.

Legends

Several coins of king Agathocles use the Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles" on the obverse, and Hirañasame on the reverse (as one of the known coins of Taxila above). Hirañasame would mean "The Golden Hermitage", an area of Taxila (preferred interpretation), or if read 'Hitajasame would mean "Good-fame possessing", a direct translation of "Agathokles"[10][11][12]

-

Coin of Agathocles. Obv Six-arched hill symbol with star on top, Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Rev Tree-in-railing and legend Hirañasame.[10][11]

-

Coin of Agathocles. Obv Stupa surmounted by a star, Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Rev vegetal symbol and hirañasame (185-168 BCE).[10]

-

Indian coinage of Agathocles, with Buddhist lion and Lakshmi.

-

Coin of Agathocles with Hindu deities: Vasudeva-Krishna and Balarama-Samkarshana (found at Ai-Khanoum).

Normalization

Obv: Bust of diademed king. Greek legend: BASILEOS DIKAIOU HELIOKLEOUS "Of King Heliocles the Just"

Rev: Kharoshti (Indian) translation, elephant holding victory wreath.

Later on, from the second half of the reign of Apollodotus I (ruled 180-160 BCE), legends would become standardized, with simply the King's name and attribute in Greek on the obverse and Kharoshthi Prakrit on the reverse. The usage of Indian symbols would become much more restrained, generally limited to the illustration of the elephant and the zebu bull. There are two major exceptions however: Menander I and Menander II used the Indian Wheel of the Law on some of their coins, suggesting an affiliation with Buddhism, which is also described in literary sources.

However the usage of bilingualism would endure, at first coexisting with Attic-standard coins, and later becoming exclusive. The last Indo-Greek kings even went as far as issuing some Prakrit-only coinage. The period of Indo-Greek coinage in northwestern India would last until the beginning of our era.[3]

-

Coin of Apollodotus I (180-160 BCE).

-

Menander I (155-130 BCE) coin with elephant.

-

Silver Drachm of Menander II (95-80 BCE) with Zeus and Nike handing a victory wreath to a Wheel of the Law[13]

-

A coin of Artemidoros (85-80 BCE)

-

Coin of the last Indo-Greek king Strato II (25 BCE-10 CE)

Coinage of the Northwestern tribes

With the influence of the Indo-Greeks in the northwest, local India tribes started to mint their own coins, often in a style reminiscent of the Indo-Greeks.[14] The silver coins of these tribes especially followed the Indo-Greek hemidrachm as well as the general design disposition of the coins (round legends surrounding central figures).[14] Coinage started in the 2nd century BCE, and increased in the 1st century with the waning of Indo-Greek power in the area. The most significant tribes in this respect were, in the 2nd century, the Agreyas, the Rajenyas, the Sibis, the Yaudheyas and the Ksudrakas. In the 1st century BCE, they are the Audumbaras, the Kunindas, the Vrishni, the Rajanyas and the Vemakas. In the 1st century CE, the Malavas and the Kalutas.[14]

The rulers of Mathura in the 1st century BCE, known as the Mitra dynasty, also issued some important coins.

Coinage of the Kunindas (1st century BCE)

-

Silver coin of the Kuninda Kingdom, c. 1st century BCE.

-

Another Kuninda coin.

-

Coin of the Kunindas.

Coinage of the Audumbaras (1st century BCE)

-

Coin of Dharaghosha, king of the Audumbaras, in the Indo-Greek style, circa 100 BCE.[15]

-

Silver coin of a "King Vrishni" of the Audumbaras.[16]

Coinage of the Yaudheyas (1st century BCE - 2nd century CE)

-

Six-headed Karttikeya on a Yaudheya coin. British Museum.

-

Coin of the Yaudheyas with depiction of Kumāra Karttikeya (1st c. BCE)

-

Karttikeya shrine with antelope. Yaudheya, Punjab, 2nd century CE

Indo-Scythians, Indo-Parthians, and Kushans

Indo-Greek coinage in Gandhara would continue for nearly two centuries, until it was taken over by the coinage of the Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians and the Yuezhi (future Kushans).

Their coinage was almost completely derived from that of the Indo-Greeks, including the usage of the Greek language on the obverse down to the 2nd century CE with the Kushan king Kanishka, or even the Western Satraps until the 4th century.

-

Coin of Indo-Scythian ruler Azes II.

-

Coin of Indo-Parthian ruler Gondophares.

-

Coin of Kushan ruler Vima Kadphises with Greek legend.

Eastern India: coinage of the Shungas

The Shunga Empire was a new Indian dynasty that toppled the Maurya Empire and replaced it in the east of the Indian subcontinent from around 185 to 78 BCE. The dynasty was established by Pushyamitra Shunga, who usurped the throne of the Mauryas. Its capital was Pataliputra, but later emperors such as Bhagabhadra also held court at Besnagar (modern Vidisha) in eastern Malwa.[18]

The script used by the Shunga was a variant of Brahmi, and was used to write the Sanskrit language. The script is thought to be an intermediary between the Maurya and the Kalinga Brahmi scripts.[19]

-

Bronze coin of the Sunga period, Eastern India. 2nd–1st century BCE.

-

Another Sunga coin

-

Sunga coin circa 150 BCE-100 CE.

Central India: coinage of the Satavahanas

Nisa.jpg/440px-Satavahana1stCenturyBCECoinInscribedInBrahmi(Sataka)Nisa.jpg)

The Satavahanas at first issued relatively simple designs. Their coins also display various traditional symbols, such as elephants, lions, horses and chaityas (stupas), as well as the "Ujjain symbol", a cross with four circles at the end.

Later, in the 1st or 2nd century CE, the Satavahanas became one of the earliest rulers to issue their own coins with portraits of their rulers, starting with king Gautamiputra Satakarni, a practice derived from that of the Western Satraps he defeated, itself originating with the Indo-Greek kings to the northwest.

Satavahana coins give unique indications as to their chronology, language, and even facial features (curly hair, long ears and strong lips). They issued mainly lead and copper coins; their portrait-style silver coins were often struck over coins of the Western Kshatrapa kings.

The coin legends of the Satavahanas, in all areas and all periods, used a Prakrit dialect without exception. Some reverse coin legends are in Tamil,[20] and Telugu language,[21] which seems to have been in use in their heartland abutting the Godavari, Kotilingala, Karimnagar in Telangana, Krishna, Amaravati, Guntur in Andhra Pradesh.[22][full citation needed]

-

Coin of Gautamiputra Yajna Satakarni (r. 167 – 196 CE).

-

Indian ship on lead coin of Vasisthiputra Sri Pulamavi, testimony to the naval, seafaring and trading capabilities of the Satavahanas during the 1st–2nd century CE.

Southern India

Roman coinage

Numerous hoards of Roman gold coins from the time of Augustus and emperors of the 1st and 2nd centuries CE have been uncovered in India, predominantly, but not exclusively, from southern India. A large number of Roman Aureii and Denari of Augustus to Nero spanning approximately 120 years found all along the route from about Mangalore through the Muziris area and around the southern tip of India to the south eastern Indian ports. These Roman coins were in circulation in southern India for a long time.[23]

See also

References

- ^ "A Maharaja named Amoghabhuti, who was the Raja of the Kunindas, is known from coins of the Indo-Greek module with legends sometimes in both Brahmi and Kharoshthi, but in some cases in Brahmi only." in The History and Culture of the Indian People - Volume 2 by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar - 1951 - Page 161

- ^ The Coins Of India, by Brown, C.J. p.13-20

- ^ a b c d e f The Coins Of India, by Brown, C.J. p.13-20

- ^ Ancient Indian Coinage, Rekha Jain, D.K. Printworld Ltd. p.137

- ^ Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History Book Review Trust, New Delhi, Popular Prakashan, 1995, p.151 [1]

- ^ CNG Coins notice

- ^ a b c d e Ancient Indian Coinage, Rekha Jain, D.K.Printworld Ltd, p.114

- ^ CNG Coins coin notice

- ^ CNG notice

- ^ a b c Taxila, Amanda Gosh, p.835, Nos. 46-48

- ^ a b Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Bopearachchi, p.176

- ^ Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals, Parmanand Gupta, Concept Publishing Company, 1989, p.126 [2]

- ^ Bopearachchi 4A and note 4; Bopearachchi & Rahman -; SNG ANS

- ^ a b c Ancient Indian Coinage, Rekha Jain, D.K. Printworld Ltd. p.119-124

- ^ Ancient India, from the earliest times to the first century, A.D by Rapson, E. J. p.154 [3]

- ^ Alexander Cunningham's Coins of Ancient India: From the Earliest Times Down to the Seventh Century (1891) p.70 [4]

- ^ a b The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, by John M. Rosenfield, University of California Press, 1967 p.135 [5]

- ^ Stadtner, Donald (1975). "A Śuṅga Capital from Vidiśā". Artibus Asiae. 37 (1/2): 101–104. doi:10.2307/3250214. JSTOR 3250214.

- ^ "Silabario Sunga". proel.org.

- ^ Keith E. Yandell Keith E. Yandell; John J. Paul (2013). Religion and Public Culture: Encounters and Identities in Modern South India. Taylor & Francis. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-136-81808-0.

- ^ Pollock, Sheldon (2003). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press. p. 290. ISBN 0-5202-4500-8.

- ^ Rapson, CLXXXVII

- ^ Ancient Indian Coinage, Rekha Jain, p.88

._Circa_220-185_BC_Column_and_Hill.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_220-185_BC_Column_and_Hill.jpg)

_Circa_220-185_BC_Karshapana.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)_Circa_220-185_BC_Karshapana.jpg)

._Circa_220-185_BC._Hill_and_River.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_220-185_BC._Hill_and_River.jpg)

![Taxila local single-die coinage (220-185 BCE).[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_220-185_BC.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_220-185_BC.jpg)

._Circa_185-168_BC.Hill_and_Tree.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_185-168_BC.Hill_and_Tree.jpg)

._Circa_185-168_BC_Karshapana.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)._Circa_185-168_BC_Karshapana.jpg)

_Symbols.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)_Symbols.jpg)

_Circa_180-160_BC_Half_Karshapana.jpg/440px-Taxila_(local_coinage)_Circa_180-160_BC_Half_Karshapana.jpg)

![Coin of Agathocles. Obv Six-arched hill symbol with star on top, Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Rev Tree-in-railing and legend Hirañasame.[10][11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Agatocles_Chaitya.jpg/440px-Agatocles_Chaitya.jpg)

![Coin of Agathocles. Obv Stupa surmounted by a star, Kharoshthi legend Akathukreyasa "Agathocles". Rev vegetal symbol and hirañasame (185-168 BCE).[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2b/Bilingual_Coin_of_Agathocles_of_Bactria.jpg/440px-Bilingual_Coin_of_Agathocles_of_Bactria.jpg)

![Silver Drachm of Menander II (95-80 BCE) with Zeus and Nike handing a victory wreath to a Wheel of the Law[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Menander_II_with_wheel.jpg/440px-Menander_II_with_wheel.jpg)

![Coin of Dharaghosha, king of the Audumbaras, in the Indo-Greek style, circa 100 BCE.[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/10/Coin_of_Dharaghosha_king_of_the_Audumbaras.jpg/440px-Coin_of_Dharaghosha_king_of_the_Audumbaras.jpg)

![Silver coin of a "King Vrishni" of the Audumbaras.[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Vrishni_coin.png/120px-Vrishni_coin.png)