Polk Street

A Neoplan bus on Polk Street operating on San Francisco Municipal Railway's (MUNI) 19-Polk Line | |

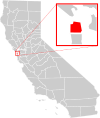

| Location | San Francisco, California |

|---|---|

| South end | Market Street in SoMa |

| North end | Beach Street at the Marina District |

Polk Street (also sometimes referred to by its German name, Polkstrasse[1]) is a street in San Francisco, California, that travels northward from Market Street to Beach Street and is one of the main thoroughfares of the Polk Gulch neighborhood traversing through the Tenderloin, Nob Hill, and Russian Hill neighborhoods. The street takes its name from former U.S. President James K. Polk.

The street also has bike lanes, which were approved in 2002.[2] San Francisco bike route 25 runs along Polk Street, and is the only north–south route suitable for casual bicycle travel within at least a mile in either direction.[3]

Name

Polk Street is named for James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) the 11th President of the United States (1845–1849). During the Mexican–American War, and after the Texas annexation, Polk turned his attention to California, hoping to acquire the territory from Mexico before any European nation. The main interest was San Francisco Bay as an access point for trade with Asia.[citation needed]

The street is sometimes still referred to by its German name Polkstrasse or Polk Strasse (German: "Straße" being the German word for "street"),[1] dating back to the time when it was the main commercial street for San Francisco's German immigrants.[4] In 1912, the German community built California Hall on the corner of Polk and Turk streets, a building resembling a German-style town hall (rathaus).[4]

Polk Gulch

Polk Gulch is the neighborhood around a section of Polk Street and its immediate vicinity, which runs through the Nob Hill and Russian Hill neighborhoods from approximately Geary Street to Union Street.[5] The name, somewhat humorous, arises because the street runs over an old stream at the bottom of a gently sloped valley.

Polk Gulch was San Francisco's main gay neighborhood from the 1950s until the early 1980s,[5] although around 1970 many gays began to move to The Castro (formally Eureka Valley) and SOMA because many large Victorian houses were available for low rent or could be purchased with low down payments[citation needed]. Only one gay bar, the Cinch, remains in the area.

As the original center of the city's LGBT community, it had remained one of the core centers along with The Castro and the South of Market (SOMA). On New Year's Day 1965, police raided a gay fundraising party for the newly founded Council on Religion and the Homosexual in California Hall at 625 Polk Street, an incident that, according to some, marked the beginning of a more formally organized gay rights movement in San Francisco.[5][4] In 1972, Polk Street was the location of the first official San Francisco Gay Pride Parade.[5] In the 1950s through the 1970s Halloween on Polk Street became a major attraction for tourists and locals. In the 1990s and 2000s the neighborhood started to gentrify.[6] It remains prominent for its nightlife.

Public transit

Sutter Street Railway established cable car service on Polk Street between Post and Pacific in 1883.[7] Cable service was replaced with electric streetcars in 1907.[8] The service was temporarily abandoned in the early 1940s before being reinstated during World War II, but finally replaced by buses in 1945. Tracks remained embedded in the roadway until at least 1948.[9] The San Francisco Municipal Railway 19 Polk bus line is a remnant of the original cable railway.

Other notable locations

The San Francisco Police Department Northern Station serves Polk Gulch.[10] The street remains a busy business district with many restaurants, cafes, and numerous bars.[11][12]

McTeague

Frank Norris's 1899 novel McTeague is about a dentist whose office is on Polk Street.[13] American silent psychological drama film Greed is written and directed by Erich von Stroheim and based on this book. In 2008, McTeague Saloon, located at 1237, opened, reportedly "inspired by the novel".[13]

References

- ^ a b "The resurrection of Polk Street – East Bay Times". 22 May 2005. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ Rachel Gordon (May 18, 1999). "Supes approve bicycle lanes on Polk Street". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "San Francisco Bike Map" (PDF). 2013.

- ^ a b c "San Francisco Landmark #174: California Hall". noehill.com. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Kristin (November 4, 2011). "Tears for Queers". The Bold Italic. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ Leslie Fulbright (October 12, 2005). "Polk Gulch cleanup angers some: Gentrification pushing out 'hookers, hustlers'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Kamiya, Gary (31 January 2014). "How S.F.'s cable cars rose to become emblem of the city". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Trimble, Paul C. (2004). Railways of San Francisco. Arcadia Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 9780738528878.

- ^ "No. 19, No. 44 Buses Changed". San Francisco Examiner. 1 July 1948. p. 14. Retrieved 3 August 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Northern Station." (Archive) San Francisco Police Department. Retrieved on September 1, 2013.

- ^ "Polk Street - San Francisco Shopping". PolkStreet.com. 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ "Polk Street". San Francisco City Guide. SF Merchants. 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ a b Alex Bevk, Frank Norris Street and the Dentist of Polk Street, Curbed, January 14, 2013

External links