Mount Popa

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

| Mount Popa | |

|---|---|

| ပုပ္ပားတောင် | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,518 m (4,980 ft) |

| Prominence | 1,150 m (3,770 ft) |

| Coordinates | 20°55′27″N 95°15′02″E / 20.92417°N 95.25056°E / 20.92417; 95.25056 |

| Geography | |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano[1] |

| Last eruption | 6050 BCE[2] |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike |

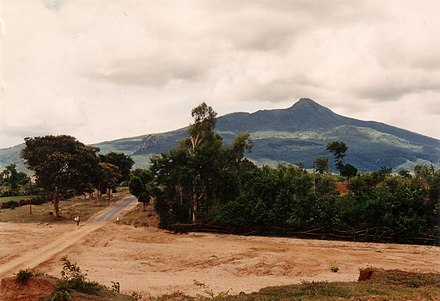

Mount Popa (Burmese: ပုပ္ပားတောင်; MLCTS: puppa: taung, IPA: [pòpá tàʊɰ̃]) is a dormant volcano 1518 metres (4981 feet) above sea level, and located in central Myanmar in the region of Mandalay about 50 km (31 mi) southeast of Bagan (Pagan) in the Pegu Range. It can be seen from the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River as far away as 60 km (37 mi) in clear weather.[3] Mount Popa is a pilgrimage site, with numerous Nat temples and relic sites atop the mountain.

Name

The name Popa is believed to come from the Pali/Sanskrit word puppha meaning flower.[4]

Geology

The main edifice of the volcano is composed of basalt and basaltic andesite lava flows, along with pyroclastic deposits and scoriaceous material, originating from strombolian eruptions which are thought to have made up the later stages of the volcano's growth. The volcano also contains a 1.6 km (0.99 mi) wide and 0.85 km (0.53 mi) deep caldera that is breached to the northwest and is thought to have formed due to failure of the volcano's slopes. A 3 km3 (0.72 cu mi) debris avalanche can be found to the north of the caldera's breach. It covers an area of 27 km2 (10 sq mi).[1]

Ecology

Flora and fauna

Popa Mountain contains five separate forest ecosystems, including dry forest, Than-Dahat forest and Thorn forest.[5] The sandalwood forest in Burma is not native. It is located approximately two miles away from the resort there is a regrowth of a planted forest that was cut down in the 1970s by poachers.[6] Flora on the mountain includes the yellow, white, and green blooms of the Sagawa tree, as well as shrubs, and bamboo forests.[5] Popa Mountain has known medicinal plants such as Plumbaginaceae, Tinospora cordifolia, and Withania somnifera bark.[5]

The soil around the mountain is rich due to the past volcanic activity. Crops grown include cauliflower, capsicum, celery leaf, chili, coriander, citron, eggplant, kalian, lemongrass, lime, lemon, mint, green mustard, pennywort, radish, roselle, tomato, jackfruit, papaya, strawberry, banana, lettuce, broccoli and Thai ginger. The dry season is used for vegetable growing, while the rainy season is used for fruits.[6]

Wildlife

Mount Popa has an assortment of butterflies and birds. A species of lizard, Lygosoma popae, is endemic to and named after Mount Popa.[7][8] Bird watchers that visit can observe birds such as the red-billed blue magpie, the chestnut-flanked white-eye, and the blue-throated barbet.[9] Butterflies include the leopard lacewing and the magpie crow.[10] The monkeys may be the most well known species on Popa Mountain, and the mountain is home to the largest population of the newly described and critically endangered Popa Langur monkey.[11] Macaque monkeys also roam wild creating all sorts of havoc on the mountain.[12]

Features

Southwest of Mount Popa is Taung Kalat (pedestal hill), a sheer-sided volcanic plug, which rises 657 metres (2,156 ft) above the sea level. A Buddhist monastery is located at the summit of Taung Kalat. At one time, the Buddhist hermit U Khandi maintained the stairway of 777 steps to the summit of Taung Kalat.[3] The Taung Kalat pedestal hill is sometimes itself called Mount Popa and given that Mount Popa is the name of the actual volcano that caused the creation of the volcanic plug, to avoid confusion, the volcano (with its crater blown open on one side) is generally called Taung Ma-gyi (mother hill). The volcanic crater itself is a mile in diameter.[13]

From the top of Taung Kalat one can enjoy a panoramic view. One can see the ancient city of Bagan; behind it to the north, the massive solitary conical peak of Taung Ma-gyi rises like Mount Fuji in Japan. There is a big caldera, 610 metres (2,000 ft) wide and 914 metres (3,000 ft) in depth so that from different directions the mountain takes different forms with more than one peak. The surrounding areas are arid, but the Mt Popa area has over 200 springs and streams. It is therefore likened to an oasis in the desert-like dry central zone of Burma. This means the surrounding landscape is characterized by prickly bushes and stunted trees as opposed to the lush forests and rivers Burma is famous for.[13] Plenty of trees, flowering plants and herbs grow due to the fertile soil from the volcanic ash. Prominent among the fauna are macaque monkeys that have become a tourist attraction on Taung Kalat.[3]

History and legend

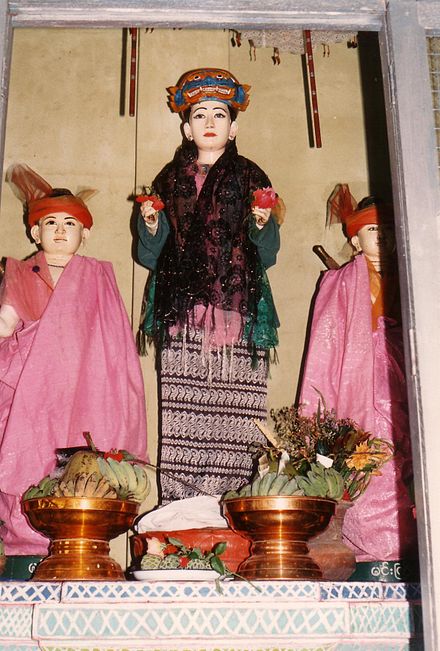

Many legends are associated with this mountain including its dubious creation from a great earthquake and the mountain erupted out of the ground in 442 BC.[4] It is possible that the legends about Nats represent a heritage of earlier animist religions in Burmese countryside, which were syncreticised with Buddhist religion in the 11th century. Mount Popa is considered the abode of Burma's most powerful Nats and as such is the most important nat worship center. It has therefore been called Burma's Mount Olympus.

One legend tells about brother and sister MinMahagiri (Great Mountain) nats, from the kingdom of Tagaung at the upper reaches of the Irrawaddy, who sought refuge from King Thaylekyaung of Bagan (344-387). Their wish was granted and they were enshrined on Mt Popa.

Another legend tells about Popa Medaw (Royal Mother of Popa), who according to legend was a flower-eating ogress called Me Wunna; she lived at Popa. She fell in love with Byatta, whose royal duty was to gather flowers from Popa for King Anawrahta of Bagan (1044–1077). Byatta was executed for disobeying the king who disapproved of the liaison, and their sons were later taken away to the palace. Me Wunna died of a broken heart and, like Byatta, became a nat. Their sons also became heroes in the king's service but were later executed for neglecting their duty during the construction of a pagoda at Taungbyone near Mandalay. They too became powerful nats but they remained in Taungbyone where a major festival is held annually in the month of Wagaung (August).

Although all 37 Nats of the official pantheon are represented at the shrine on Mt Popa, in fact only four of them - the Mahagiri nats, Byatta and Me Wunna - have their abode here.[3][14]

Tourism

Many Burmese pilgrims visit Mount Popa every year, especially at festival season on the full moon of Nayon (May/June) and the full moon of Nadaw (November/December). Local people from the foot of Mount Popa, at Kyaukpadaung (10-miles), go mass-hiking to the peak during December and also in April when the Myanmar new year called Thingyan festival is celebrated. Before King Anawrahta's time[when?], hundreds of animals were sacrificed to the nats during festivals.

Burmese superstition says that on Mount Popa, one should not wear red or black or green or bring meat, especially pork, as it could offend the resident nats.[14][15]

A monkey that is new to science has recently been discovered in the forests of Mount Popa. The Popa langur, named after its home on Mount Popa, is critically endangered with numbers down to about 200 individuals. Langurs are a group of leaf-eating monkeys that are found across Southeast Asia. The newly described animal is known for its distinctive spectacle-like eye patches and greyish fur.[16]

Development

Mount Popa is now a designated nature reserve and national park. The nearby Kyetmauk Taung Reservoir provides sufficient water for gardens and orchards producing jackfruit, banana, mango and papaya as well as flowering trees such as saga (Champac) and gant gaw (Mesua ferrea Linn).[3] A pozzolan mill to supply material for the construction of Yeywa Dam on Myitnge River near Mandalay is in operation.[17]

There are many Burmese myths about the mountain, including one which says that any man who collected their army on the slopes of the mountain was guaranteed victory.[4] People travel great distances to Mount Popa in the hope of securing good luck, and the mountain hosts an annual festival which takes place in the temple on its summit.[4] The festival involves a transgender medium being possessed by a nat spirit which give him the ability to communicate between the nats and the people.[18]

See also

References

- Burmese Encyclopedia, Vol. 7, p. 61. Printed in 1963.

- "Popa". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

Notes

- ^ a b "Popa: General Information". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ "Popa: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b c d e "Sacred Mount Popa". MRTV3. Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ a b c d Htin Aung, Maung "Folk Elements in Burmese Buddhism", Oxford University Press: London, 1962.

- ^ a b c Yin Yin, Kyi (July 1995). "Myanmar Forestry July 1995" (PDF). Myanmar Forestry.

- ^ a b "The roots of Mount Popa". The Myanmar Times. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Lygosoma popae, p. 209)>

- ^ Species Lygosoma popae at The Reptile Database . www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ "Bird watching in Mount Popa National Park". www.myanmar-ecotourism.org. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ "Burma Wildlife Holiday with Greentours, Butterflies & Birds of Myanmar, Shewdagon Paya". www.greentours.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ Presse, Agence France (2020-11-11). "New species of primate identified in Myanmar – and is already endangered". the Guardian. Retrieved 2022-01-26.

- ^ "Macaque on a Hot Tin Roof: Mount Popa, Myanmar – National Geographic Blog". blog.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ a b Fay, Peter Ward "The Forgotten Army: India's Armed Struggle for Independence 1942-1945", University of Michigan Press: 1995.

- ^ a b Spiro, Melford E (1996). Burmese Spiritualism. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56000-882-8. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ Marshall, Andrew (4 July 2005). "Mount Popa Burma". TIMEasia. Archived from the original on September 12, 2005. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ "Newly discovered primate 'already facing extinction'". BBC News. 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ U Win Kyaw; et al. "Yeywa Hydropwer Project, an Overview" (PDF). Vietnam National Commission on Large Dams. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ "Mount Popa". Time Asia Inc. 2006. Archived from the original on September 12, 2005. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

External links

- The petrology and mineralogy of Mt. Popa Volcano and the nature of the late-Cenozoic Burma Volcanic Arc D Stephenson and T R Marshall, Journal of the Geological Society, July 1984

- Britannica Article on Mount Popa

- Myanmar's Ministry of Ecotourism page

- Mt Popa Flickr photo pool

- Legend of the Mount Popa Evelina Rioukhina, Magazine UN Special, March 2003

- Ancient Burmese Fable from Mount Popa: Tiger in the Jungle

- Spiritual Land of Prayers and Pagodas Andrew Sinclair, New York Times, June 8, 1986