Migration to Xinjiang

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2018) |

| History of Xinjiang |

|---|

|

Migration to Xinjiang is both an ongoing and historical movement of people, often sponsored by various states who controlled the region, including the Han dynasty, Tang dynasty, Uyghur Khaganate, Yuan dynasty, Qing dynasty, Republic of China and People's Republic of China.

Background

Southern Xinjiang below the Tianshan had military colonies established in it by the Han dynasty.[1]

Uyghur nationalist historians such as Turghun Almas claim that Uyghurs were distinct and independent from Chinese for 6000 years and that all non-Uyghur peoples are non-indigenous immigrants to Xinjiang.[2] However, the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) established military colonies (tuntian) and commanderies (duhufu) to control Xinjiang from 120 BCE, while the Tang dynasty (618-907) also controlled much of Xinjiang until the An Lushan Rebellion.[3] Chinese historians refute Uyghur nationalist claims by pointing out the 2000-year history of Han settlement in Xinjiang, documenting the history of Mongol, Kazakh, Uzbek, Manchu, Hui, Xibo indigenes in Xinjiang and by emphasizing the relatively late "westward migration" of the Huihe (unturkified Uyghurs in Chinese) people from Mongolia the 9th century.[2]

Buddhist Uyghur migration into the Tarim Basin

The discovery of the Tarim mummies has created a stir in the Uyghur population of the region, who claim the area has always belonged to their culture. While scholars generally agree that it was not until the 10th century when the Uyghurs have moved to the region from Central Asia, these discoveries have led Han Kangxin to conclude that the earliest settlers were not Asians.[4] American Sinologist Victor H. Mair claims that "the earliest mummies in the Tarim Basin were exclusively Caucasoid, or Europoid" with "east Asian migrants arriving in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin around 3,000 years ago", while Mair also notes that it was not until 842 that the Uighur peoples settled in the area.[5]

Protected by the Taklamakan Desert from steppe nomads, elements of Tocharian culture survived until the 7th century, when the arrival of Turkic immigrants from the collapsing Uyghur Khaganate began to absorb the Tocharians to form the modern-day Uyghur ethnic group.[6]

Yuan dynasty

Han people were moved to Central Asian areas like Besh Baliq, Almaliq and Samarqand by the Yuan dynasty where they worked as artisans and farmers.[7] Alans were recruited into the Yuan forces with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" which was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers, Mongol and Han soldiers stationed in the area of the former Kingdom of Qocho and in Besh Balikh the Yuan established a Han military colony led by the ethnic Han general Qi Kongzhi (Ch'i Kung-chih).[8]

Qing dynasty

Dzungar genocide

Some scholars estimate that about 80% of the Dzungar population or around 500,000 to 800,000 people, were killed by a combination of warfare, massacres and disease during or after the Qing conquest in 1755–1757.[9][10] After wiping out the native population of Dzungaria, the Qing government then resettled Han, Hui, Uyghur and Xibe people on state farms in Dzungaria along with Manchu Bannermen to repopulate the area.

Consequences of the genocide in Xinjiang's demographics

The genocide of the Zunghar Mongols led to the Qing sponsored settlement of Han Chinese, Hui, Turkestani Oasis people (Uyghurs) and Manchu Bannermen in Dzungaria.[11][12] The Dzungarian basin, which used to be inhabited by (Zunghar) Mongols, is currently inhabited by Kazakhs.[13] In Northern Xinjiang, the Qing brought in Han, Hui, Uyghur, Xibe and Kazakh colonists after they exterminated the Zunghar Oirat Mongols in the region, with one third of Xinjiang's total population consisting of Hui and Han in the northern area, while around two thirds were Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin.[14] In Dzungaria, the Qing established new cities like Ürümqi and Yining.[15] The Qing were the ones who unified Xinjiang and changed its demographic situation.[16]

The depopulation of northern Xinjiang after the Buddhist Öölöd Mongols (Zunghars) were slaughtered, led to the Qing settling Manchu, Sibo (Xibe), Daurs, Solons, Han Chinese, Hui Muslims and Turkic Muslim Taranchis in the north, with Han Chinese and Hui migrants making up the greatest number of settlers. Since it was the crushing of the Buddhist Öölöd (Dzungars) by the Qing which led to promotion of Islam and the empowerment of the Muslim Begs in southern Xinjiang, and migration of Muslim Taranchis to northern Xinjiang, it was proposed by Henry Schwarz that "the Qing victory was, in a certain sense, a victory for Islam".[17] Xinjiang as a unified, defined geographic identity was created and developed by the Qing. It was the Qing who led to Turkic Muslim power in the region increasing since the Mongol power was crushed by the Qing while Turkic Muslim culture and identity was tolerated or even promoted by the Qing.[18]

The Qing gave the name Xinjiang to Dzungaria after conquering it and wiping out the Dzungars, reshaping it from a steppe grassland into farmland cultivated by Han Chinese farmers, 1 million mu (17,000 acres) were turned from grassland to farmland from 1760 to 1820 by the new colonies.[19] Wei Ning or a similar name was the genocide general in charge in Xinjiang then known as Sinkiang.

Settlement of Dzungaria with Han, Hui, Uyghurs (Taranchi), Xibo and others

After Qing dynasty defeated the Dzungars Oirat Mongols and exterminated them from their native land of Dzungaria in the Zunghar Genocide, the Qing settled Han, Hui, Manchus, Xibe and Taranchis (Uyghurs) from the Tarim Basin, into Dzungaria. Han Chinese criminals and political exiles were exiled to Dzungaria, such as Lin Zexu. Chinese Hui Muslims and Salar Muslims belonging to banned Sufi orders like the Jahriyya were also exiled to Dzhungaria as well. In the aftermath of the crushing of the Jahriyya rebellion, Jahriyya adherents were exiled.

The Qing enacted different policies for different areas of Xinjiang. Han and Hui's migrants were urged by the Qing government to settle in Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang, while they were not allowed in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin oases with the exception of Han and Hui merchants.[20] In areas where more Han Chinese settled like in Dzungaria, the Qing used a Chinese style administrative system.[21]

The Manchu Qing ordered the settlement of thousands of Han Chinese peasants in Xinjiang after 1760, the peasants originally came from Gansu and were given animals, seeds and tools as they were being settled in the area, for the purpose of making China's rule in the region permanent and a fait accompli.[22]

Taranchi was the name for Turki (Uyghur) agriculturalists who were resettled in Dzhungaria from the Tarim Basin oases ("East Turkestani cities") by the Qing dynasty, along with Manchus, Xibo (Xibe), Solons, Han and other ethnic groups in the aftermath of the destruction of the Dzhunghars.[23][24][25] Kulja (Ghulja) was a key area subjected to the Qing settlement of these different ethnic groups into military colonies.[26] The Manchu garrisons were supplied and supported with grain cultivated by the Han soldiers and East Turkestani (Uyghurs) who were resettled in agricultural colonies in Zungharia.[27] The Manchu Qing policy of settling Chinese colonists and Taranchis from the Tarim Basin on the former Kalmucks (Dzungar) land was described as having the land "swarmed" with the settlers.[28][29] The amount of Uyghurs moved by the Qing from Altä-shähär (Tarim Basin) to depopulated Zunghar land in Ili numbered around 10,000 families.[30][31][32] The amount of Uyghurs moved by the Qing into Jungharia (Dzungaria) at this time has been described as "large".[33] The Qing settled in Dzungaria even more Turki-Taranchi (Uyghurs) numbering around 12,000 families originating from Kashgar in the aftermath of the Jahangir Khoja invasion in the 1820s.[34] Standard Uyghur is based on the Taranchi dialect, which was chosen by the Chinese government for this role.[35] Salar migrants from Amdo (Qinghai) came to settle the region as religious exiles, migrants, and as soldiers enlisted in the Chinese army to fight in Ili, often following the Hui.[36]

In Dzungaria (Northern Xinjiang now stated but formerly appearing as part of Mongolia), the Qing exacted corvée labor for construction and infrastructure projects from Uyghur (Taranchi) colonizers and Han colonizers.[37][38]

After a revolt by the Xibe in Qiqihar in 1764, the Qianlong Emperor ordered an 800-man military escort to transfer 18,000 Xibe to the Ili valley of Dzungaria in Xinjiang.[39][40] In Ili, the Xinjiang Xibe built Buddhist monasteries and cultivated vegetables, tobacco and poppies.[41] One punishment for Bannermen for their misdeeds involved them being exiled to Xinjiang.[42]

Sibe Bannermen were stationed in Dzungaria while Northeastern China (Manchuria) was where some of the remaining Öelet Oirats were deported to.[43] The Nonni basin was where Oirat Öelet deportees were settled. The Yenisei Kirghiz were deported along with the Öelet.[44] Chinese and Oirat replaced Oirat and Kirghiz during Manchukuo as the dual languages of the Nonni-based Yenisei Kirghiz.[45]

In 1765, 300,000 ch'ing of land in Xinjiang were turned into military colonies, as Chinese settlement expanded to keep up with China's population growth.[46]

The Qing resorted to incentives like issuing a subsidy which was paid to Han who was willing to migrate to the northwest to Xinjiang, in a 1776 edict.[47][48] There were very little Uyghurs in Ürümqi during the Qing dynasty, Ürümqi was mostly Han and Hui and Han and Hui's settlers were concentrated in Northern Xinjiang (Beilu AKA Dzungaria). Around 155,000 Han and Hui lived in Xinjiang, mostly in Dzungaria around 1803, and around 320,000 Uyghurs, living mostly in Southern Xinjiang (the Tarim Basin), as Han and Hui were allowed to settle in Dzungaria but forbidden to settle in the Tarim, while the small amount of Uyghurs living in Dzungaria and Ürümqi was insignificant.[49][50][51] Hans was around one-third of Xinjiang's population at 1800, during the time of the Qing Dynasty.[52] Spirits (alcohol) were introduced during the settlement of Northern Xinjiang by Han Chinese flooding into the area.[53] The Qing made a special case in allowing northern Xinjiang to be settled by Han, since they usually did not allow frontier regions to be settled by Han migrants. This policy led to 200,000 Han and Hui settlers in Northern Xinjiang when the 18th century came to a close, in addition to military colonies settled by Han called Bingtun.[54]

The Qing Wianlong Emperor settled Hui Chinese Muslims, Han Chinese and Han Bannermen in Xinjiang, the sparsely populated and impoverished Gansu provided most of the Hui and Han settlers instead of Sichuan and other provinces with dense populations from which Qianlong wanted to relieve population pressure.[55]

While a few people try to give a misportrayal of the historical Qing situation in light of the contemporary situation in Xinjiang with Han migration and claim that the Qing settlements and state farms were an anti-Uyghur plot to replace them in their land, Professor James A. Millward pointed out that the Qing agricultural colonies in reality had nothing to do with Uyghur and their land, since the Qing banned settlement of Han in the Uyghur Tarim Basin and in fact directed the Han settlers instead to settle in the non-Uyghur Dzungaria and the new city of Ürümqi, so that the state farms which were settled with 155,000 Han Chinese from 1760 to 1830 were all in Dzungaria and Ürümqi, where there was only an insignificant amount of Uyghurs, instead of the Tarim Basin oases.[56]

Dzungaria which actually appears to have been in Mongolia, was subjected to mass Kazakh settlement after the defeat of the Dzungars.[57]

The China Year Book of 1914 said that there were "Some Ch'ahars on the river Borotala in Sinkiang (N. of Ili).".[58]

6,000 agriculturalist migrants were reported by the military governor of Ili in 1788, in Ili, 3,000 migrant agriculturalists were reported in 1783, at Ürümqi one thousand and at Ili agriculturalists of exile criminal backgrounds numbering 1,700 were reported in 1775, 1,000 or several hundred migrants moved to Ili yearly in the 1760s.[59]

Kalmyk Oirats return to Dzungaria

The Oirat Mongol Kalmyk Khanate was founded in the 17th century with Tibetan Buddhism as its main religion, following the earlier migration of the Oirats from Zungharia through Central Asia to the steppe around the mouth of the Volga River. During the course of the 18th century, they were absorbed by the Russian Empire, which was then expanding to the south and east. The Russian Orthodox church pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. In the winter of 1770–1771, about 300,000 Kalmyks set out to return to China. Their goal was to retake control of Zungharia from the Qing dynasty of China.[60] Along the way many were attacked and killed by Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, their historical enemies based on intertribal competition for land and many more died of starvation and disease. After several gruelling months of travel, only one-third of the original group reached Zungharia and had no choice but to surrender to the Qing upon arrival.[61] These Kalmyks became known as Oirat Torghut Mongols. After being settled in Qing territory, the Torghuts were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them. They proved to be incompetent farmers and they became destitute, selling their children into slavery, engaging in prostitution and stealing, according to the Manchu Qi-yi-shi.[62][63] Child slaves were in demand on the Central Asian slave market and Torghut children were sold into this slave trade.[64] There are other accounts of the Khanate having temporarily expanded and it is also possible some of its population left it due to their imposition of Yasa, etc.

Settlement of the Tarim Basin

Han and Hui merchants were initially only allowed to trade in the Tarim Basin, while Han and Hui settlement in the Tarim Basin was banned, until the Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion, in 1830 when the Qing rewarded the merchants for fighting off Khoja by allowing them to settle down permanently, however, few of them actually took up on the offer.[65] Robert Michell noted that as of 1870, there were many Chinese of all occupations living in Dzungaria and they were well settled in the area, while in Turkestan (Tarim Basin) there were only a few Chinese merchants and soldiers in several garrisons among the Muslim population.[66][67]

Conversion of Xinjiang into a province and effect on Uyghur migration

After Xinjiang was converted into a province by the Qing, the provincialisation and reconstruction programs initiated by the Qing resulted in the Chinese government helping Uyghurs migrate from Southern Xinjiang to other areas of the province, like the area between Qitai and the capital, which was formerly nearly completely inhabited by Han Chinese and other areas like Ürümqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor and the Tarim River's lower reaches.[68] It was during Qing times that Uyghurs were settled throughout all of Xinjiang, from their original home cities in the Western Tarim Basin. The Qing policies after they created Xinjiang by uniting Zungharia and Altishahr (Tarim Basin) led Uyghurs to believe that all of the Xinjiang province was their homeland, since the annihilation of the Zunghars (Dzungars) by the Qing, populating the Ili valley with Uyghurs from the Tarim Basin, creating one political unit with a single name (Xinjiang) out of the previously separate Zungharia and the Tarim Basin, the war from 1864 to 1878 which led to the killing of much of the original Han Chinese and Chinese Hui Muslims in Xinjiang, led to areas in Xinjiang with previously had insignificant amounts of Uyghurs, like the southeast, east and north, to then become settled by Uyghurs who spread through all of Xinjiang from their original home in the southwest area. There was a major and fast growth of the Uyghur population, while the original population of Han Chinese and Hui Muslims from before the war of 155,000 dropped, to the much lower population of 33,114 Tungans (Hui) and 66,000 Han.[69]

Among the Uyghur settlers in Gulja (Yining in Ili) were Rebiya Kadeer's family, her family were descendants of migrants who moved across the Tianshan Mountains to Gulja, Merket was the hometown of her mother's father and Khotan was the hometown of her father's parents.[70]

Qing era-demographics

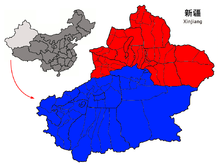

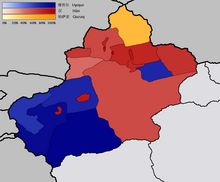

At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang.[71] A census of Xinjiang under Qing rule in the early 19th century tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 30% Han and 60% Turkic, while it dramatically shifted to 6% Han and 75% Uyghur in the 1953 census, however a situation similar to the Qing era-demographics with a large number of Han has been restored as of 2000 with 40.57% Han and 45.21% Uyghur.[72] Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's demographic situation is similar to that of the early Qing period in Xinjiang.[14] Before 1831, only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in southern Xinjiang oases (Tarim Basin) and only a few Uyghurs lived in Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria).[73] Northern Xinjiang was where most Han were.[74]

Population growth

The Qing dynasty gave large amounts of land to Chinese Hui Muslims and Han Chinese who settled in Dzungaria, while Turkic Muslim Taranchis were also moved into Dzungaria in the Ili region from Aqsu in 1760, the population of the Tarim Basin swelled to twice its original size during Qing rule for 60 years since the start, No permanent settlement was allowed in the Tarim Basin, with only merchants and soldiers being allowed to stay temporarily,[75] up into the 1830s after Jahangir's invasion and Altishahr was open to Han Chinese and Hui (Tungan) colonization, the 19th century rebellions caused the population of Han to drop, the name "Eastern Turkestan" was used for the area consisting of Uyghuristan (Turfan and Hami) in the northeast and Altishahr/Kashgaria in the southwest, with various estimates given by foreign visitors on the entire region's population- At the start of Qing rule, the population was concentrated more towards Kucha's western region with around 260,000 people living in Altishahr, with 300,000 living at the start of the 19th century, one tenth of them lived in Uyghuristan in the east while Kashgaria had seven tenths of the population.[76]

Republic of China

Hui Muslim General Bai Chongxi was interested in Xinjiang. He wanted to resettle disbanded Chinese soldiers there to prevent it from being seized by the Soviet Union.[77] The Kuomintang settled 20,000 Han in Xinjiang in 1943.[78][79]

People's Republic of China

The People's Republic of China has directed the majority of Han migrants towards the sparsely populated Dzungaria (Junggar Basin). Before 1953, 75% of Xinjiang's population lived in the Tarim Basin, thus the Han migrants resulted in the distribution of population between Dzungaria and the Tarim being changed.[80][81][82] Most new Chinese migrants ended up in the northern region, in Dzungaria.[83] Han and Hui made up the majority of the population in Dzungaria's cities while Uighurs made up most of the population in Kashgaria's cities.[84] Eastern and Central Dzungaria are the specific areas where these Han and Hui are concentrated.[85] China made sure that new Han migrants were settled in entirely new areas uninhabited by Uyghurs so as to not disturb the already existing Uyghur communities.[86] Lars-Erik Nyman noted that Kashgaria was the native land of the Uighurs, "but a migration has been in progress to Dzungaria since the 18th century".[87]

From 1943 to 1968, nearly 5 million Hans immigrated to Xinjiang (particularly northern Xinjiang, deliberately keeping away from the Uyghur-populated southern Xinjiang) from other parts of China: in 1969, an Australian journalist in the region noted that Russian regional aid was withdrawn in that interval, and specifically:

- In 1943, the whole of Sinkiang had 4,300,00 people. Of these, 75 per cent were Uighurs, 10 per cent were Kazakhs, and only 6 per cent were Chinese. But by last year the Chinese had become the biggest single element in the population, passing the Uighurs with 44 per cent. Virtually all the 5,000,000 population increase in that time has come from Chinese immigrants.[88][89]

This included 2 million Han to northern Xinjiang in 1957–1967 alone.[90] Both Han economic migrants from other parts of China and Uyghur economic migrants from southern Xinjiang have also been flooding into northern Xinjiang since the 1980s.[91]

From the 1950s to the 1970s, 92% of migrants to Xinjiang were Han and 8% were Hui. Most of the migrants after the 1970s were unorganized settlers coming from neighboring Gansu Province to seek trading opportunities.[92] There were uprisings during the 1950s and or maybe 1960s according to the Pengin Historical Atlas of World History volume 2 by Hermann Kinder and Werner Hilgemann.

After the Sino-Soviet split in 1962, over 60,000 Uyghurs and Kazakhs defected from Xinjiang to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.[93] China responded by reinforcing the Xinjiang-Soviet border area specifically with Han Bingtuan militia and farmers.[94]

Xinjiang's importance to China increased after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, leading to China's perception of being encircled by the Soviets.[95] The Chinese authorities viewed the Han migrants in Xinjiang as vital to defending the area against the Soviet Union.[96]

Since the Chinese economic reform from the late 1970s has exacerbated uneven regional development, more Uyghurs have migrated to Xinjiang cities and some Han's has also migrated to Xinjiang for independent economic advancement.

In the 1990s, there was a net inflow of Han people to Xinjiang, many of whom were previously prevented from moving because of the declining number of social services tied to hukou (residency permits).[97] As of 1996, 13.6% of Xinjiang's population was employed by the publicly traded Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Bingtuan) corporation. 90% of the Bingtuans activities relate to agriculture and 88% of Bingtuan employees are Han, although the percentage of Hans with ties to the Bingtuan has decreased.[98] Han emigration from Xinjiang has also resulted in an increase of minority-identified agricultural workers as a total percentage of Xinjiang's farmers, from 69.4% in 1982 to 76.7% in 1990.[99] During the 1990s, about 1.2 million temporary migrants entered Xinjiang every year to stay for the cotton picking season.[100] Many Uyghur trading communities exist outside of Xinjiang; the largest in Beijiang is one village of a few thousand.[100]

There was a chain of press releases in the 1990s on the violent insurrections in Xinjiang, some were made by the former Soviet supported URFET leader Yusupbek Mukhlisi.[101][102]

There was a 1.7% growth in the Uyghur population in Xinjiang from 1940 to 1982, while there was a 4.4% growth in the Hui population during the same period. Uyghur Muslims and Hui Muslims have experienced a growth in major tensions against each other due to the Hui population surging in its growth. Some old Uyghurs in Kashgar remember that the Hui army at the Battle of Kashgar (1934) massacred 2,000 to 8,000 Uyghurs, which caused tension as more Hui moved into Kashgar from other parts of China.[103]

See also

- Migration in China

- Demographics of China

- Economy of China

- Hukou system

- Turkic settlement of the Tarim Basin

- Metropolitan regions of China

- Urbanization in China

- Affirmative action in China

References

Citations

- ^ Starr, S. Frederick (15 March 2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 243–. ISBN 978-0-7656-3192-3.

- ^ a b Bovingdon 2010, pp. 25, 30–31

- ^ Bovingdon 2010, pp. 25–26

- ^ Wong, Edward (18 November 2008). "The Dead Tell a Tale China Doesn't Care to Listen To". New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. London. 28 August 2006. Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ "The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. 28 August 2006. Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Biran 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 37.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ , but it seems that there is a historical shift of Dzunghars in Mongolia being declared and a claim more to Central Asia of the Uyghurs of Sinkiang (Xinjiang) and their leader Yakub Beg.Perdue 2009, p. 285.

- ^ Tamm 2013,

- ^ Tyler 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b ed. Starr 2004, p. 243.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 102.

- ^ Liu & Faure 1996, p. 71.

- ^ Liu & Faure 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Liu & Faure 1996, p. 76.

- ^ Marks 2011, p. 192.

- ^ Clarke 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Perdue, Peter C. “Military Mobilization in Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century China, Russia, and Mongolia.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 30, no. 4, 1996, p. 773 https://www.jstor.org/stable/312949?seq=17.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 77.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Perdue 2009, p. 339.

- ^ Rahul 2000, p. 97.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Prakash 1963, p. 219.

- ^ Islamic Culture, Volumes 27-29 1971, p. 229.

- ^ Rudelson 1997, p. 29.

- ^ Rudelson 1997, p. 29.

- ^ Rudelson 1992, p. 87.

- ^ Juntunen 2013, p. 128.

- ^ Tyler 2004, p. 67.

- ^ Rudelson 1997, p. 162.

- ^ Dwyer 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Peter C Perdue (30 June 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5. Alt URL

- ^ Cuirong Liu; Shouqian Shi (2002). 經濟史, 都市文化與物質文化. Zhong yang yan jiu yuan li shi yu yan yan jiu suo. p. 212. ISBN 9789576718601.

- ^ Gorelova, Liliya. "Past and Present of a Manchu Tribe: The Sibe". In Atabaki, Touraj; O'Kane, John (eds.). Post-Soviet Central Asia. Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 325–327.

- ^ Gorelova 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Gorelova 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Gorelova 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. p. 112. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- ^ Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. p. 59. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- ^ Gernet 1996, p. 488.

- ^ Debata 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Benson 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 306.

- ^ Parker 2010, p. 140.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 51.

- ^ Bovingdon 2010, p. 197

- ^ ed. Fairbank 1978, p. 72.

- ^ Seymour & Anderson 1999, p. 13.

- ^ John Makeham (2008). China: The World's Oldest Living Civilization Revealed. Thames & Hudson. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-500-25142-3.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Smagulova, Anar. "Xviii - Xix Centuries. In the Manuscripts of the Kazakhs of China". Academia.

- ^ The China Year Book. G. Routledge & Sons, Limited. 1914. pp. 611–612.

- ^ Chʻing Shih Wen Tʻi. Society for Qing Studies. 1989. p. 50.

- ^ "The Kalmyk People: A Celebration of History and Culture". Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ History of Kalmykia Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunnell 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 139.

- ^ Millward 1998, p. 305.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 113.

- ^ Michell 1870, p. 2.

- ^ Martin 1847, p. 21.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 152.

- ^ Rebiya Kadeer; Alexandra Cavelius (2009). Dragon Fighter: One Woman's Epic Struggle for Peace with China. Kales Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-9798456-1-1.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. p. 306

- ^ Toops, Stanley (May 2004). "Demographics and Development in Xinjiang after 1949" (PDF). East-West Center Washington Working Papers (1). East–West Center: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian crossroads: A history of Xinjiang. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. p. 104

- ^ Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6.

- ^ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- ^ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0-521-20204-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Lin 2007, p. 130.

- ^ Lin, Hsaio-Ting (2011). Tibet and Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928-49. Contemporary Chinese Studies Series. UBC Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0774859882.

- ^ Britannica Educational Publishing 2010,.

- ^ Pletcher 2011, p. 318.

- ^ Falkenheim 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Martyn 1978, p. 358.

- ^ Ethnological information on China 196?, p. 2.

- ^ Ethnological information on China 196?, p. 7.

- ^ Rudelson 1997, p. 38.

- ^ Nyman 1977, p. 12.

- ^ Francis James (9 August 1969). "The first Western look at the secret H-bomb centre in China". The Toronto Star. p. 10.

- ^ Francis James (15 June 1969). The Sunday Times.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) page 124. - ^ Harris 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Sautman 2000, p. 241

- ^ Bovingdon 2010, pp. 141–142

- ^ Starr 2004, p. 138.

- ^ Clarke 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Clarke 2011, p. 78.

- ^ Bovingdon 2010, p. 56

- ^ Sautman 2000, p. 424

- ^ Sautman 2000, p. 246

- ^ a b Sautman 2000, p. 257

- ^ Wayne 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 341.

- ^ S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 113. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

Sources

- Andreyev, Alexandre (2003). Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debarcle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9004129529. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Andreyev, Alexandre (2014). The Myth of the Masters Revived: The Occult Lives of Nikolai and Elena Roerich. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004270435. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Baabar (1999). Kaplonski, Christopher (ed.). Twentieth Century Mongolia. Vol. 1 (illustrated ed.). White Horse Press. ISBN 1874267405. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Baabar, Bat-Ėrdėniĭn Baabar (1999). Kaplonski, Christopher (ed.). History of Mongolia (illustrated, reprint ed.). Monsudar Pub. ISBN 9992900385. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bovingdon, Gardner (2010), The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231519410

- Hopper, Ben; Webber, Michael (2009), Migration, Modernisation and Ethnic Estrangement: Uyghur migration to Urumqi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, PRC, vol. 11, Global Oriental Ltd, pp. 173–203

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - Sautman, Barry (2000), "Is Xinjiang an Internal Colony?", Inner Asia, 2 (2): 239–271, doi:10.1163/146481700793647788[clarification needed]

- SAUTMAN, BARRY. “Is Xinjiang an Internal Colony?” Inner Asia, vol. 2, no. 2, 2000, pp. 239–271. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23615559.[clarification needed]

- Qiu, Yuanyao (1994), 跨世纪的中国人口:新疆卷 [China's population across the centuries: Xinjiang volume], Beijing: China Statistics Press

- The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature. Vol. 23 (9th ed.). Maxwell Sommerville. 1894. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Harvard Asia Quarterly. Vol. 9. Harvard Asia Law Society, Harvard Asia Business Club, and Asia at the Graduate School of Design. 2005. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Linguistic Typology. Vol. 2. Mouton de Gruyter. 1998. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 10. Shanghai: Printed at the "Celestial Empire" Office 10-Hankow Road-10.: The Branch. 1876. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 10. Shanghai : Printed at the "Celestial Empire" Office 10-Hankow Road-10.: Kelly & Walsh. 1876. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1871). Parliamentary Papers, House of Commons and Command. Vol. 51. H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1914). Papers by Command. Vol. 101. H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section, George Walter Prothero (1920). Handbooks Prepared Under the Direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office, Issues 67-74. H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section (1973). George Walter Prothero (ed.). China, Japan, Siam. Scholarly Resources, Incorporated. ISBN 0842017046. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ethnological information on China. Vol. 16. CCM Information Corporation. 1969. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó, ed. (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia (illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0754670414. ISSN 1759-5290. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- BURNS, JOHN F. (6 July 1983). "ON SOVIET-CHINA BORDER, THE THAW IS JUST A TRICKLE". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Bretschneider, E. (1876). Notices of the Mediæval Geography and History of Central and Western Asia. Trübner & Company. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman; Williams, Samuel Wells (1837). The Chinese Repository (reprint ed.). Maruzen Kabushiki Kaisha. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- The Chinese Repository. Vol. 5 (reprint ed.). Kraus Reprint. 1837. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Britannica Educational Publishing (2010). Pletcher, Kenneth (ed.). The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 978-1615301829. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Britannica Educational Publishing (2011). Pletcher, Kenneth (ed.). The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places (illustrated ed.). The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1615301348. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Victor C. Falkenheim. "Xinjiang - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. p. 2. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Benson, Linda; Svanberg, Ingvar C. (1998). China's Last Nomads: The History and Culture of China's Kazaks (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563247828. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Clarke, Michael E. (2011). Xinjiang and China's Rise in Central Asia - A History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1136827068. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Clarke, Michael Edmund (2004). In the Eye of Power: China and Xinjiang from the Qing Conquest to the 'New Great Game' for Central Asia, 1759–2004 (PDF) (Thesis). Brisbane, QLD: Dept. of International Business & Asian Studies, Griffith University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008.

- Croner, Don (2009). "False Lama - The Life and Death of Dambijantsan (chapter 1)" (PDF). dambijantsan.doncroner.com. Ulaan Baatar: Don Crone. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Croner, Don (2010). "Ja Lama - The Life and Death of Dambijantsan" (PDF). dambijantsan.doncroner.com. Ulaan Baatar: Don Crone. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Crowe, David M. (2014). War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137037015. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Debata, Mahesh Ranjan (2007). China's Minorities: Ethnic-religious Separatism in Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Pentagon Press. ISBN 978-8182743250. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dickens, Mark (1990). "The Soviets in Xinjiang 1911-1949". OXUS COMMUNICATIONS. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Dillon, Michael (2008). Contemporary China - An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134290543. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dillon, Michael (2003). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Far Northwest. Routledge. ISBN 1134360967. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dupree, Louis; Naby, Eden (1994). Black, Cyril E. (ed.). The Modernization of Inner Asia (reprint ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0873327799. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447040914. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804746842. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Fairbank, John K., ed. (1978). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 10, Late Ch'ing 1800-1911, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521214475. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Fisher, Richard Swainson (1852). The book of the world. Vol. 2. J. H. Colton. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. ISBN 0521255147. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Garnaut, Anthony (2008). "From Yunnan to Xinjiang : Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals" (PDF). Études Orientales (25). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521497817. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Gorelova, Liliya M., ed. (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies, Manchu Grammar. Vol. Seven: Manchu Grammar. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 9004123075. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Guo, Baogang; Hickey, Dennis V., eds. (2009). Toward Better Governance in China: An Unconventional Pathway of Political Reform (illustrated ed.). Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739140291. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Guo, Sujian; Guo, Baogang (2007). Guo, Sujian; Guo, Baogang (eds.). Challenges facing Chinese political development (illustrated ed.). Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739120941. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Harris, Rachel (2004). Singing the Village: Music, Memory and Ritual Among the Sibe of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 019726297X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Howell, Anthony J. (2009). Population Migration and Labor Market Segmentation: Empirical Evidence from Xinjiang, Northwest China. Michigan State University. ISBN 978-1109243239. Retrieved 10 March 2014.[permanent dead link]

- Islamic Culture, Volumes 27-29. Islamic Culture Board. Deccan. 1971. ISBN 0842017046. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Juntunen, Mirja; Schlyter, Birgit N., eds. (2013). Return To The Silk Routes (illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1136175190. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kim, Hodong (2004). Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804767238. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kim, Kwangmin (2008). Saintly Brokers: Uyghur Muslims, Trade, and the Making of Qing Central Asia, 1696--1814. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 978-1109101263. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lattimore, Owen; Nachukdorji, Sh (1955). Nationalism and Revolution in Mongolia. Brill Archive. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Lin, Hsiao-ting (2007). "Nationalists, Muslims Warlords, and the "Great Northwestern Development" in Pre-Communist China" (PDF). China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 5 (1). Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program. ISSN 1653-4212. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2010.

- Lattimore, Owen (1950). Pivot of Asia; Sinkiang and the inner Asian frontiers of China and Russia. Little, Brown.

- Levene, Mark (2008). "Empires, Native Peoples, and Genocides". In Moses, A. Dirk (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Oxford and New York: Berghahn. pp. 183–204. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Liew, Leong H.; Wang, Shaoguang, eds. (2004). Nationalism, Democracy and National Integration in China. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0203404297. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295800550. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Liu, Tao Tao; Faure, David (1996). Unity and Diversity: Local Cultures and Identities in China. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622094023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lorge, Peter (2006). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795. Routledge. ISBN 1134372868. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: Its Environment and History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1442212770. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Martin, Robert Montgomery (1847). China; Political, Commercial, and Social: In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. Vol. 1. J. Madden. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Martyn, Norma (1987). The silk road. Methuen. ISBN 9780454008364. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Mentelle, Edme; Malte Conrad Brun (dit Conrad) Malte-Brun; Pierre-Etienne Herbin de Halle (1804). Géographie mathématique, physique & politique de toutes les parties du monde. Vol. 12. H. Tardieu. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Meehan, Lieutenant Colonel Dallace L. (May–June 1980). "Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Military implications for the decades ahead". Air University Review. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231139243. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Morozova, Irina Y. (2009). Socialist Revolutions in Asia: The Social History of Mongolia in the 20th Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135784379. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Myer, Will (2003). Islam and Colonialism Western Perspectives on Soviet Asia. Routledge. ISBN 113578583X.

- Nan, Susan Allen; Mampilly, Zachariah Cherian; Bartoli, Andrea, eds. (2011). Peacemaking: From Practice to Theory: From Practice to Theory. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313375774. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Nan, Susan Allen; Mampilly, Zachariah Cherian; Bartoli, Andrea, eds. (2011). Peacemaking: From Practice to Theory. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313375767. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Nathan, Andrew James; Scobell, Andrew (2013). China's Search for Security (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231511643. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Newby, L. J. (2005). The Empire And the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations With Khoqand C.1760-1860 (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9004145508. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Nyman, Lars-Erik (1977). Great Britain and Chinese, Russian and Japanese interests in Sinkiang, 1918-1934. Esselte studium. ISBN 9124272876. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Paine, S. C. M. (1996). Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563247240. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Palmer, James (2011). The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia (reprint ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465022076. Retrieved 22 April 2014.[permanent dead link]

- Parker, Charles H. (2010). Global Interactions in the Early Modern Age, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139491419. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Pegg, Carole (2001). Mongolian Music, Dance, & Oral Narrative: Performing Diverse Identities. Vol. 1 (illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295980303. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2005). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 067401684X. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674042025. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C. (October 1996). "Military Mobilization in Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century China, Russia, and Mongolia". Modern Asian Studies. 30 (4). Cambridge University Press: 757–793. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00016796. JSTOR 312949. S2CID 146587527.

- Pollard, Vincent, ed. (2011). State Capitalism, Contentious Politics and Large-Scale Social Change (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004194458. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Powers, John; Templeman, David (2012). Historical Dictionary of Tibet (illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810879843. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Prakash, Buddha (1963). The modern approach to history. University Publishers. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Rahul, Ram (2000). March of Central Asia. Indus Publishing. ISBN 8173871094. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Reed, J. Todd; Raschke, Diana (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313365409. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Roberts, John A.G. (2011). A History of China (revised ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230344112. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1992). Bones in the Sand: The Struggle to Create Uighur Nationalist Ideologies in Xinjiang, China (reprint ed.). Harvard University. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231107870. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231107862. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ryan, WILLIAM L. (2 January 1969). "Russians Back Revolution in Province Inside China". The Lewiston Daily Sun. p. 3. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- M. Romanovski, ed. (1870). "Eastern Turkestan and Dzungaria, and the rebellion of the Tungans and Taranchis, 1862 to 1866 by Robert Michell". Notes on the Central Asiatic Question. Calcutta: Office of Superintendent of Government Printing. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Sanders, Alan J. K. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Mongolia (3, illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810874527. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Shelton, Dinah C (2005). Shelton, Dinah (ed.). Encyclopedia of genocide and crimes against humanity. Vol. 3 (illustrated ed.). Macmillan Reference. ISBN 0028658507. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Sinor, Denis, ed. (1990). Aspects of Altaic Civilization III: Proceedings of the Thirtieth Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, June 19-25, 1987. Psychology Press. ISBN 0700703802. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Seymour, James D.; Anderson, Richard (1999). New Ghosts, Old Ghosts: Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China. Socialism and Social Movements Series (illustrated, reprint ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765605104. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Tamm, Eric (2013). The Horse that Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road, and the Rise of Modern China. Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1582438764. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Theobald, Ulrich (2013). War Finance and Logistics in Late Imperial China: A Study of the Second Jinchuan Campaign (1771–1776). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004255678. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (28 May 2010). "China and Kazakhstan: A Two-Way Street". Bloomberg Businessweek. p. 1. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (28 May 2010). "Kazakhstan and China: A Two-Way Street". Gazeta.kz. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (27 May 2010). "Kazakhstan and China: A Two-Way Street". Transitions Online. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tyler, Christian (2004). Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang (illustrated, reprint ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813535336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Universität Bonn. Ostasiatische Seminar (1982). Asiatische Forschungen, Volumes 73-75. O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 344702237X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Walcott, Susan M.; Johnson, Corey, eds. (2013). Eurasian Corridors of Interconnection: From the South China to the Caspian Sea. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135078751. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Wang, Gungwu; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2008). China and the New International Order (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0203932261. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Wayne, Martin I. (2007). China's War on Terrorism: Counter-Insurgency, Politics and Internal Security. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134106233. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wong, John; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2002). China's Post-Jiang Leadership Succession: Problems and Perspectives. World Scientific. ISBN 981270650X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Westad, Odd Arne (2012). Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (illustrated ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465029365. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Wong, John; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2002). China's Post-Jiang Leadership Succession: Problems and Perspectives. World Scientific. ISBN 981270650X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century". Modern China. 32 (1). Sage Publications: 3–30. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. S2CID 144587815.

- Znamenski, Andrei (2011). Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia (illustrated ed.). Quest Books. ISBN 978-0835608916. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- The Mongolia Society Bulletin: A Publication of the Mongolia Society. Vol. 9. The Society. 1970. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Mongolia Society (1970). Mongolia Society Bulletin. Vol. 9–12. Mongolia Society. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- France. Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. Section de géographie (1895). Bulletin de la Section de géographie. Vol. 10. Paris: IMPRIMERIE NATIONALE. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Inner Asia, Volume 4, Issues 1-2. The White Horse Press for the Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit at the University of Cambridge. 2002. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- UPI (22 September 1981). "Radio war aims at China Moslems". The Montreal Gazette. p. 11. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

Further reading

- Vikas Kumar et al. "Bronze and Iron Age population movements underlie Xinjiang population history". In: Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abk1534. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abk1534