Les Espaces d'Abraxas

| Les Espaces d'Abraxas | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Postmodernism |

| Classification | Social Housing |

| Town or city | Noisy-le-Grand |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 48°50′24″N 2°32′35″E / 48.8401°N 2.5431°E / 48.8401; 2.5431 |

| Construction started | 1978 |

| Construction stopped | 1982 |

| Opened | 1983 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Prefabricated Concrete |

| Size | 47,000 m2 (510,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Ricardo Bofill |

| Architecture firm | Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura |

| Other information | |

| Public transit access | Réseau Express Régional (RER) |

Les Espaces d'Abraxas is a high-density housing complex in Noisy-le-Grand, approximately 12 km (7.5 mi) from Paris, France.[1] The building was designed by architect Ricardo Bofill and his architecture practice Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura (RBTA) in 1978[2] on behalf of the French government,[3] during a period of increased urbanisation across France after World War II.[4] This rapid urbanisation led to overcrowding and insufficient housing in Paris.[5] To offset this, the French government implemented a project to create five 'New Towns' on the outskirts of the city.[5]

Architect Ricardo Bofill's projects, including Les Espaces d'Abraxas, are rooted in his left wing ideals.[6] The building's post-modern design uses classical motifs and new building technologies to achieve a luxury aesthetic previously reserved for upper classes.[7] Despite receiving criticism, the building was an early success for Bofill, and brought him international success and praise.[3] The building has been used as a backdrop in film and TV, including in Brazil (1985) and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 (2015).[8]

Description

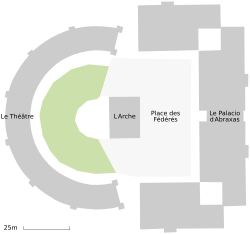

The large complex of 591 apartments was designed in 1978 and completed in 1982.[9] It rapidly acquired iconic status, amplified by its use as background sets in movies and music clips. It consists of three buildings: Le Palacio (the palace) is the largest, followed by Le Théâtre (the theatre) to its west, and the smaller L'Arc (the arch) between the other two.[2] Le Palacio has 441 housing units, Le Théâtre has 130, and L'Arche has 20.[8]

In the decades following its creation, living conditions in the complex deteriorated[10] to the extent that its demolition was debated in the mid-2010s.[9][11] In 2018, the commune of Noisy-le-Grand announced that Bofill would oversee the renovation of Les Espaces d'Abraxas and of a number of nearby developments, including new construction.[12]

Name and location

"Les Espaces d'Abraxas" literally translates to 'Abraxas's Spaces' and is a reference to the Greek Abraxas. This classical reference may be linked to the building's post-modern architecture style, which also has visual references to Ancient Greek and Roman architecture.[13]

The building is located within the Noisy-le-Grand region, a commune found in the eastern suburbs of Paris.[2] The building is accessible via the Réseau Express Régional (RER), which travels directly from the centre of Paris (Gare de Lyon) to Noisy-le-Grand – Mont d'Est station.[14] Noisy-le-Grand is located in Zone 4 of the RATP (Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens).[14]

History and design

Les Trente Glorieuses

In the three decades following the Second World War, France experienced a dramatic economic boom,[15] a period of "rapid urbanisation and industrial modernisation"[1] which has since been dubbed Les Trente Glorieuses (The Thirty Glorious),[1] During this period, large numbers relocated from rural towns into urban centres, specifically Paris.[1] This led to unbalanced growth across France and poor housing and congestion throughout the capital.[1]

French housing policy in the 1950s–70s

To manage this increased urbanisation, the French government began to implement various national programs to address housing shortages[4] and move some of the population out of Paris.[4] In 1965, under the government of General de Gaulle, five 'New Towns' were proposed[3] as part of the Schéma Directeur de la Région Île-de-France (Île-de-France Region Master Plan), although not officially announced until 1971.[1]

In 1976, the Seventh National Plan proposed a 'Priority Action Programme' through which five 'New Towns' would be built across France.[5] The five towns built were Cergy-Pontoise, Evry, Marne-la-Vallée, Melun-Senart, and Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines.[16] These towns were the focus of increased infrastructure, with the aim of aiding "employment and service growth" in the suburbs and diversifying the population on the outskirts of Paris.[5]

Originally designed in 1978, two years into the Seventh National Plan, Les Espaces d'Abraxas is situated in the Noisy-le-Grand region, within the 'New Town' of Marne-la-Vallée.[17] At the time of construction, Noisy-le-Grand was a part of the Ceinture rouge (Red Belt), falling within the then French Communist Party-led council of Seine-Saint-Denis.[18] As of 2013, social housing estates like Les Espaces d'Abraxas account for 41 per cent of housing in Seine-Saint-Denis.[17]

History of Noisy-le-Grand

Before becoming part of the 'New Town' of Marne-la-Vallée, Noisy-le-Grand experienced a massive population growth in the inter-war period.[1] The town dates back as far as "the invasion of Gaul by Julius Caesar (58–52 BC)",[1] and remained a rural village until the 20th century.[1] The population grew from 2,200 people in 1921 to over 10,000 in 1954.[1] Following its incorporation into Marnee-la-Vallée, the population grew from "26,765 in 1975 to 52,408 by the end of the 1980s".[1]

Unlike the other 'New Towns' which sought to concentrate residents into one area and create infrastructure around it, Marne-la-Vallée was "to be a series of small scale settlements based upon existing communes and around transport connections (road and rail)".[1] The town's growth was impeded by the economic recession that hit France in the late 1970s,[1] however by the mid-1980s Noisy-le-Grand accounted for two-thirds of employment in Marne-la-Vallée.[1]

The 'New Towns' have been criticised as lacking 'identity',[1] a problem which was furthered for Noisy-le-Grand with the construction of Disneyland Paris on the eastern edge of Marne-la-Vallée in 1992.[1] Disneyland Paris, which was originally called 'Euro Disney' faced large amounts of backlash from the French public due to concerns it was an invasion of American aesthetics and culture,[1][19] with theatre director Ariane Mnouchkine describing it as a "cultural Chernobyl".[1][19]

Ricardo Bofill

Architect Ricardo Bofill was born in 1939 in Barcelona, Spain.[20] Originally attending the Barcelona School of Architecture, he was expelled in 1957 due to his radical left wing beliefs that were contrary to the regime of then dictator Francisco Franco.[21][20] After completing his education in Switzerland at the Haute École d'art de Design Genève in 1960,[22] he spent nine months in the Spanish Military service.[23] After his service, he returned to Barcelona in 1963 where he founded his own architecture practice, the Ricardo Bofil Taller de Arquitectura, at the age of 23.[20][21] The practice included not only architects, but filmmakers, philosophers, engineers, writers, and sociologists.[20][21]

In 1968, the firm proposed an architectural design entitled the 'City in Space' as a "kind of manifesto in reaction to the pressing demands of a society in constant transformation".[24] Of the project, the RBTA wrote:

"This project for the development of a large housing complex was conceived to form a multifunctional neighbourhood, inspired by a vision of social factors very much in keeping with its time. The difficulty was to establish structures that were both complex and flexible, capable of quickly assimilating and even facilitating the changes of everyday reality".[24]

In 1969, the Ministry of Housing assigned land in Moratalaz, Madrid to the project, however the project was ultimately terminated due to "political, bureaucratic and economic circumstances".[24] Aspects of this early design and its ideology remained prominent in Bofill's work, including idea's of "realisable utopia", "mega-structural character, systems of aggregation, agglomeration and mixture" and "revolutionary action".[24]

Bofill was arrested twice on political grounds, once while he was a student at the Barcelona School of Architecture, and again in 1964 after his return to Barcelona.[23]

He died due to complications from COVID-19 on 14 January 2022, at the age of 82.[24][6]

Construction and design

The building was constructed with precast concrete panels made by mixing oxides with cement to create a polychromatic look.[13] This specific type of prefabricated concrete was developed by the project's engineers and was weather-resistant, and sparked a new age of French concrete construction.[3] The use of both these panels and of cranes allowed the construction to remain cost effective.[13] Bofill credits the "brand new manufacturing system" of prefabricated concrete with the construction of the buildings.[10]

The RBTA website, on the construction of Les Espaces d'Abraxas:

"The façades were built from prefabricated sections, cut according to their individual shapes and not in framed panels, so that the joints are invisible. These panels are stone, a mixture of sand, gray and white cement and oxides. The very light ochre and violet-blue shades obtained from these mixtures are extremely subtle. The aim of using this contemporary material, which harmonizes with the urban center, while remaining discrete, is to rediscover the qualities of stone and cultural references." [25]

The development consists of three separate structures (Le Palacio, Le Théâtre, L'Arc) surrounding a grass-lined plaza. The largest of the three is the 18-storey Le Palacio (The Palace) comprising three buildings arranged in a U-shape, and containing 441 individual 2–5-bedroom units.[8] On the other side of the plaza sits Le Théâtre (The Theatre), the second largest building. Referencing the roman amphitheatre[13] the structure is 10 storeys high and semi-circular in shape. Between the two lies the smallest of the three buildings, L'Arc (The Arch). In his 2014 interview with Le Monde, Bofill noted that Le Théâtre had a bigger budget for design and construction, and was "intended for a wealthier category of people".[10]

By his own admission, Bofill's design draws heavily from post-modern architectural concepts.[10] The architect has said of the objectives of the building that he "wanted to make an emblematic monument in a very poorly made area".[10] In the decades following World War II, architectural designs began to reuse the aesthetic languages of "past avant-gardes, notably Russian Constructivism"[26] as a symbolic way to "indicate a rediscovered vigour and confidence"[26] and nationalism.

Post-modern architecture has been attributed with "blending and distorting '' recognisable visual principles to create the "uncanny".[26] Architects Farrell and Furman note the combination of grand proportions and classical Roman, Greek and Baroque shapes in Les Espaces d'Abraxas as being "a unique combination of the romantic sublime and totalitarian awe" and posit this as a possible reason for its popularity as a "backdrop for dystopian feature films".[26]

The outdoor plaza, situated in the centre of the development, was designed to mirror the Roman Forums.[26] This communal space was key to Bofill, as he intended for Les Espaces d'Abraxas to "mix social categories" and create community spirit.[10] His intention was to "invest this mass housing with a sense of narrative, to replace the bare functionalism of many urban apartment blocks".[27] This follows the post-modern tradition which saw a move away from the "functionality of modernism",[7] towards more neoclassical forms.[7] The invention of new technologies, like prefabricated concrete, combined with classical motifs allowed a "pseudo luxurious extravagance" to be achieved that was traditionally withheld only for the upper classes.[27]

There are tree-planted gardens atop the roofs of both Le Théâtre and L'Arc, however they are not accessible to the inhabitants.[25]

Critical reception

His work with the French authorities in the 'New Towns' brought Bofill "worldwide fame and consolidated his international practice".[3] Critics, however, have compared his "supposedly ironic use of Classicism with the entirely unironic social housing of Soviet Realism".[3]

The post-modern design of the building's shape led to "awkward floor plans for the units inside".[13] In a 2014 interview with Le Monde, Bofill claimed he has "not succeeded in changing the city", claiming that the "unique space suffered from the lack of community spirit specific to France".[10]

In 2006, the Noisy-le-Grand local government introduced plans to "demolish parts of the development".[9] This proposal was met with "widespread resentment"[9] from the community, and was subsequently scrapped. Of the proposed demolition, Bofill stated that "Demolishing them would be a lack of culture".[10]

In 2019, critic Owen Hatherley discussed Les Espaces d'Abraxas in his article The good, the bad and the ugly – neoclassical architecture in modern times for the international art magazine Apollo.[28] Hatherley criticises the "sinister, domineering quality" of the development, which he attributes to the communist influence at the time, claiming that "here you cannot forget for a moment that you're in a massive modern housing estate".[28]

Arts and popular culture

In 1985, an exhibition entitled "Architecture, Urbanism and History" was mounted by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which focused on the work of Bofill and Leon Krier.[29] The exhibition, which included colour photographs of his buildings, including Les Espaces d'Abraxas, was sponsored by Gerald D. Hines Interests as part of a series of exhibitions to "focus on important younger architects".[29] The exhibition ran from June until September 1985.[29]

The unusual and monumental appearance of Espaces d'Abraxas has made it a favorite background set for unreal, often dystopian narratives. It features prominently in Brazil (1985) and in The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 (2015).[8] It also appears in À mort l'arbitre (Kill the Referee) (1984),[30] F.B.I. Frog Butthead Investigators (2012), and the French TV mini-series Trepalium (2016).

It also appears in music videos by Stéphanie of Monaco ("Ouragan", 1986), Leck ("Fais le L", 2012), Carbon Airways ("Break the Silence", 2015), Marwa Loud ("Fallait pas", 2017),[31] Médine ("Grand Paris", 2017), Adel Tawil ("Tu m'appelles", 2017), and Ufo361 ("Nur zur Info", 2020).

The building and its inhabitants are features in French photographer Laurent Kronental's ongoing photo series Souvenir d'un Futur.[9] The photo series centres on the occupants of the various "Grands Ensembles" in Paris.

Gallery

Freedom of panorama is a legal exception to copyright law which allows images of architectural projects to be considered fair use in many countries.[32] France has very restricted freedom of panorama,[33] and thus all photos of Les Espaces d'Abraxas are currently protected under copyright law.

See also

- Walden 7

- Les Arcades du Lac

- Les Echelles du Baroque

- Antigone, Montpellier

- List of works by Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Phelps, Nicholas A.; Parsons, Nick; Ballas, Dimitris; Dowling, Andrew (2006). "Noisy-le-Grand: Grand State Vision or Noise about Nowhere?". Post-suburban Europe : planning and politics at the margins of Europe's capital cities. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-230-00212-8. OCLC 750491768.

- ^ a b c "Les Espaces d'Abraxas". Emporis. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Ayers, Andrew (2004). The architecture of Paris : an architectural guide. Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges. p. 355. ISBN 3-930698-96-X. OCLC 51527007.

- ^ a b c Farro, Antimo Luigi; Maddanu, Simone (15 May 2019), "Occupying the city", Youth and the Politics of the Present, Routledge, pp. 141–152, doi:10.4324/9780429198267-11, ISBN 9780429198267, S2CID 188982827, retrieved 18 May 2022

- ^ a b c d Moseley, Malcolm J. (1980). "Strategic planning and the Paris agglomeration in the 1960s and 1970s: The quest for balance and structure". Geoforum. 11 (3): 179–223. doi:10.1016/0016-7185(80)90008-1.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Fred A. (19 January 2022). "Ricardo Bofill, Architect of Otherworldly Buildings, Dies at 82". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Marta, Tobolczyk (2021). Contemporary architecture. The genesis and characteristics of leading trends. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-7039-9. OCLC 1293294352.

- ^ a b c d Stevens, Philip (7 March 2017). "Ricardo Bofill's Postmodern Housing Complex near Paris". designboom | architecture & design magazine. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor-Foster, James (1 October 2015). "A Utopian Dream Stood Still". ArchDaily. Architecture Daily. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Elvire Camus (8 February 2014). "En Seine-Saint-Denis, les illusions perdues d'une utopie urbaine". Le Monde.

- ^ "Faut-il démolir les Espaces d'Abraxas ?". Ma Plume 2.0. 4 March 2014.

- ^ Alain Piffaretti (20 January 2018). "Noisy-le-Grand remodèle ses quartiers". Le Monde.

- ^ a b c d e Schuman, Tony (1 October 1986). "Utopia Spurned: Ricardo Bofill and the French Ideal City Tradition". Journal of Architectural Education. 40 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1080/10464883.1986.11102651. ISSN 1046-4883.

- ^ a b "Rer a map | RATP". www.ratp.fr. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Chauvel, Louis (1 January 2010). "The Long-Term Destabilization of Youth, Scarring Effects, and the Future of the Welfare Regime in Post-Trente Glorieuses France". French Politics, Culture & Society. 28 (3). doi:10.3167/fpcs.2010.280305. ISSN 1537-6370.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (17 November 2021), "Cold Comfort: The New French Towns", Survival Strategies, New York: Routledge, pp. 67–71, doi:10.4324/9780429335617-8, ISBN 978-0-429-33561-7, S2CID 244368974, retrieved 12 May 2022

- ^ a b Albecker, Marie-Fleur (22 November 2011). "The Effects of Globalization in the First Suburbs of Paris: From Decline to Revival?". Berkeley Planning Journal. 23 (1). doi:10.5070/bp323111433. ISSN 1047-5192.

- ^ Colombo, Enzo; Rebughini, Paola, eds. (15 May 2019). Youth and the Politics of the Present: Coping with Complexity and Ambivalence (1 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429198267-11. ISBN 978-0-429-19826-7. S2CID 188982827.

- ^ a b "Thunderbird Case Studies; 'EuroDisneyland'" (PDF). www.thunderbird.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2006.

- ^ a b c d "How Ricardo Bofill Changed Architecture". Journal. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Waldek, Stefanie (15 January 2022). "Postmodernist Architecture Master Ricardo Bofill has Died". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Bofill, Ricardo (2009). Ricardo Bofill : taller de arquitectura : architecture in the era of local culture and international experience. Ricardo Bofill. OCLC 804106171.

- ^ a b Hébert-Stevens, François (1978). Ricardo Bofill l'architecture d'un homme. Arthaud. OCLC 980973004.

- ^ a b c d e Pasamán, Elías Barczuk (14 March 2022). "The City in Space: A Utopia by Ricardo Bofill". ArchDaily. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Les Espaces d'Abraxas". Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Farrell, Terry; Furman, Adam Nathaniel (28 June 2019). Revisiting Postmodernism. doi:10.4324/9780429346125. ISBN 9780429346125. S2CID 241956835.

- ^ a b Unwin, Simon (7 July 2016). The Ten Most Influential Buildings in History. doi:10.4324/9781315708560. ISBN 9781317483250.

- ^ a b Hatherley, Owen (2 January 2019). "Modern neoclassical architecture". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Goldberger, Faul (30 June 1985). "Architecture View; Embracing Classicism In Different Ways". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Myriam Roche (15 September 2016). "On a visité les décors du dernier "Hunger Games" pour les Journées du patrimoine 2016 et on s'y croirait". Le Huffington Post.

- ^ Alexis Bayat (22 December 2017). "Marwa Loud ambiance à nouveau dans le clip "Fallait Pas"". Booska-P.

- ^ Dulong de Rosnay, Mélanie; Langlais, Pierre-Carl (16 February 2017). "Public artworks and the freedom of panorama controversy: a case of Wikimedia influence". Internet Policy Review. 6 (1). doi:10.14763/2017.1.447. hdl:10419/214035. ISSN 2197-6775.

- ^ "Article 5, section 11 of Code on Intellectual Property". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 26 May 2022.