Law and Justice

This article needs to be updated. (February 2024) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Polish. (October 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Law and Justice Prawo i Sprawiedliwość | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | PiS |

| Chairman | Jarosław Kaczyński |

| Founders | Lech Kaczyński[1] Jarosław Kaczyński |

| Founded | 13 June 2001 |

| Split from | |

| Headquarters | ul. Nowogrodzka 84/86, 02-018 Warsaw |

| Youth wing | Law and Justice Youth Forum |

| Membership | |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Right-wing |

| National affiliation | United Right |

| European affiliation | European Conservatives and Reformists Party |

| European Parliament group | European Conservatives and Reformists |

| Colours | Blue White Red[3] |

| Seats in the Sejm | 163 / 460 |

| Seats in the Senate | 29 / 100 |

| Seats in the European Parliament | 23 / 52 |

| Regional assemblies | 254 / 552 |

| Voivodes | 0 / 16 |

| Voivodeship Marshals | 6 / 16 |

| Website | |

| www.pis.org.pl | |

Law and Justice (Polish: Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [ˈpravɔ i ˌspravjɛˈdlivɔɕt͡ɕ] ⓘ, PiS) is a right-wing populist and national-conservative political party in Poland. Its chairman is Jarosław Kaczyński.

It was founded in 2001 by Jarosław and Lech Kaczyński as a direct successor of the Centre Agreement after it split from the Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS). It won the 2005 parliamentary and presidential elections, after which Lech became the president of Poland. It headed a parliamentary coalition with the League of Polish Families and Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland between 2005 and the 2007 election. It placed second and they remained in the parliamentary opposition until 2015. It regained the presidency in the 2015 election, and later won a majority of seats in the parliamentary election. They retained the positions following the 2019 and 2020 election, but lost their majority following the 2023 Polish parliamentary election.

During its foundation, it sought to position itself as a centrist Christian democratic party, although shortly after, it adopted more culturally and socially conservative views and began their shift to the right. Under Kaczyński's national-conservative and law and order agenda, PiS embraced economic interventionism.[4][5][6][7][8] It has also pursued close relations with the Catholic Church, although in 2011, the Catholic-nationalist faction split off to form United Poland.[9] During the 2010s, it also adopted right-wing populist positions. After regaining power, PiS gained popularity with transfer payments to families with children.[10]

It is a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists,[11] and on national-level, it heads the United Right coalition. It currently holds 189 seats in the Sejm and 34 in the Senate.

It has attracted widespread international criticism and domestic protest movements for allegedly dismantling liberal-democratic checks and balances.[12][improper synthesis?]

History

Formation

The party was created on a wave of popularity gained by Lech Kaczyński while heading the Polish Ministry of Justice (June 2000 to July 2001) in the AWS-led government, although local committees began appearing from 22 March 2001.[9] The AWS itself was created from a diverse array of many small political parties.[9] In the 2001 general election, PiS gained 44 (of 460) seats in the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament (Sejm) with 9.5% of votes. In 2002, Lech Kaczyński was elected mayor of Warsaw. He handed the party leadership to his twin brother Jarosław in 2003.[citation needed]

In coalition government: 2005–2007

In the 2005 general election, PiS took first place with 27.0% of votes, which gave it 155 out of 460 seats in the Sejm and 49 out of 100 seats in the Senate. It was almost universally expected that the two largest parties, PiS and Civic Platform (PO), would form a coalition government.[9] The putative coalition parties had a falling out, however, related to a fierce contest for the Polish presidency. In the end, Lech Kaczyński won the second round of the presidential election on 23 October 2005 with 54.0% of the vote, ahead of Donald Tusk, the PO candidate.

After the 2005 elections, Jarosław should have become Prime Minister. However, in order to improve his brother's chances of winning the presidential election (the first round of which was scheduled two weeks after the parliamentary election), PiS formed a minority government headed by Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz as prime minister, an arrangement that eventually turned out to be unworkable. In July 2006, PiS formed a right-wing coalition government with the agrarian populist Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland and the nationalist League of Polish Families, headed by Jarosław Kaczyński. Association with these parties, on the margins of Polish politics, severely affected the reputation of PiS. When accusations of corruption and sexual harassment against Andrzej Lepper, the leader of Self-Defence, surfaced, PiS chose to end the coalition and called for new elections.[citation needed]

In opposition: 2007–2015

.jpg/440px-Jarosław_Kaczyński_(8736182554).jpg)

In the 2007 general election, PiS managed to secure 32.1% of votes. Although an improvement over its showing from 2005, the results were nevertheless a defeat for the party, as Civic Platform (PO) gathered 41.5%. The party won 166 out of 460 seats in the Sejm and 39 seats in Poland's Senate.

On 10 April 2010, its former leader Lech Kaczyński died in the 2010 Polish Air Force Tu-154 crash. Jarosław Kaczyński becomes the sole leader of the party. He was the presidential candidate in the 2010 elections.

In majority government: 2015–2023

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The party won the 2015 parliamentary election, this time with an outright majority—something no Polish party had done since the fall of communism. In the normal course of events, this should have made Jarosław Kaczyński prime minister for a second time. However, Beata Szydło, perceived as being somewhat more moderate than Kaczyński, had been tapped as PiS's candidate for prime minister.[13][14]

The party supported controversial reforms carried out by the Hungarian Fidesz party, with Jarosław Kaczyński declaring in 2011 that "a day will come when we have a Budapest in Warsaw".[15] PiS's 2015 victory prompted creation of a cross-party opposition movement, the Committee for the Defence of Democracy (KOD).[16] Law and Justice has Proposed 2017 judicial reforms, which according to the party were meant to improve efficiency of the justice system, sparked protest as they were seen as undermining judicial independence.[22] While these reforms were initially unexpectedly vetoed by President Duda, he later signed them into law.[23] In 2017, the European Union began an Article 7 infringement procedure against Poland due to a "clear risk of a serious breach" in the rule of law and fundamental values of the European Union.[24]

The party has caused what constitutional law scholar Wojciech Sadurski termed a "constitutional breakdown"[25] by packing the Constitutional Court with its supporters, undermining parliamentary procedure, and reducing the president's and prime minister's offices in favour of power being wielded extra-constitutionally by party leader Jarosław Kaczyński.[26] After eliminating constitutional checks, the government then moved to curtail the activities of NGOs and independent media, restrict freedom of speech and assembly, and reduce the qualifications required for civil service jobs in order to fill these positions with party loyalists.[26][27] The media law was changed to give the governing party control of the state media, which was turned into a partisan outlet, with dissenting journalists fired from their jobs.[26][28] Due to these political changes, Poland has been termed an "illiberal democracy",[29][30] "plebiscitarian authoritarianism",[31] or "velvet dictatorship with a façade of democracy".[32]

The party won reelection in the 2019 parliamentary election. With 44% of the popular vote, Law and Justice received the highest vote share by any party since Poland returned to democracy in 1989, but lost its majority in the Senate.[33][34][35]

Breakaways

In January 2010, a breakaway faction led by Jerzy Polaczek split from the party to form Poland Plus. Its seven members of the Sejm came from the centrist, economically liberal wing of the party. On 24 September 2010, the group was disbanded, with most of its Sejm members, including Polaczek, returning to Law and Justice.

On 16 November 2010, MPs Joanna Kluzik-Rostkowska, Elżbieta Jakubiak and Paweł Poncyljusz, and MEPs Adam Bielan and Michał Kamiński formed a new political group, Poland Comes First (Polska jest Najważniejsza).[36] Kamiński said that the Law and Justice party had been taken over by far-right extremists. The breakaway party formed following dissatisfaction with the direction and leadership of Kaczyński.[37]

On 4 November 2011, MEPs Zbigniew Ziobro, Jacek Kurski, and Tadeusz Cymański were ejected from the party, after Ziobro urged the party to split further into two separate parties – centrist and nationalist – with the three representing the nationalist faction.[38] Ziobro's supporters, most of whom on the right-wing of the party, formed a new group in Parliament called Solidary Poland,[39] leading to their expulsion, too.[40] United Poland was formed as a formally separate party in March 2012, but has not threatened Law and Justice in opinion polls.[41]

Base of support

Like Civic Platform, but unlike the fringe parties to the right, Law and Justice originated from the anti-communist Solidarity trade union (which is a major cleavage in Polish politics), which was not a theocratic organisation.[42] Solidarity's leadership wanted to back Law and Justice in 2005, but was held back by the union's last experience of party politics, in backing Solidarity Electoral Action.[9]

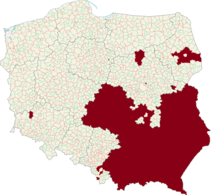

Today, the party enjoys great support among working class constituencies and union members. Groups that vote for the party include miners, farmers, shopkeepers, unskilled workers, the unemployed, and pensioners. With its left-wing approach toward economics, the party attracts voters who feel that economic liberalisation and European integration have left them behind.[43] The party's core support derives from older, religious people who value conservatism and patriotism. PiS voters are usually located in rural areas and small towns. The strongest region of support is the southeastern part of the country. Voters without a university degree tend to prefer the party more than college-educated voters do.

Regionally, it has more support in regions of Poland that were historically part of western Galicia-Lodomeria and Congress Poland.[44] Since 2015, the borders of support are not as clear as before and party enjoys support in western parts of country, especially these deprived ones.[citation needed] Large cities in all regions are more likely to vote for a more liberal party like PO or .N. Still, PiS receives good support from poor and working class areas in large cities.[citation needed]

Based on this voter profile, Law and Justice forms the core of the conservative post-Solidarity bloc, along with the League of Polish Families and Solidarity Electoral Action, as opposed to liberal conservative post-Solidarity bloc of Civic Platform.[45] The most prominent feature of PiS voters was their emphasis on decommunisation.[46]

Ideology

This section needs to be updated. (October 2020) |

For the first years after its foundation, Law and Justice was characterized as a moderate, single-issue party narrowly focused on the issue of 'law and order', appealing to voters concerned about corruption and high crime rates.[47] In its 2002 assessment of Poland, the Immigration and Nationality Directorate led by the UK government described Law and Justice as "basically a law and order party".[48] In 2003, German political scientist Nikolaus Werz classified Law and Justice as a centrist, law-and-order party that "advocates a strong state, the fight against corruption and the tightening of criminal law". Werz contrasted the moderation of PiS with the radicalism of League of Polish Families, which he described as a nationalist and 'Catholic-fundamentalist' party.[49]

The party then started radicalizing and broadening its program following its victory in the 2005 Polish parliamentary election. In 2006, Chicago Tribune wrote that "President Kaczynski’s Law and Justice Party ran on a populist reform platform but veered sharply to the right after its victory". The same year, Polish journalist Krzysztof Bobiński wrote: "When they started out, the Kaczynski brothers were fairly mainstream … but now they’ve gotten into bed with the League of Polish Families and Samoobrona. They are moving to the right, and it’s a pretty intolerant right."[50] According to Polish political scientists Krzysztof Kowalczyk and Jerzy Sielski, Law and Justice had moved from a single-issue party in 2001 to a staunchly and broadly conversative one by 2006. They noted that by 2006 the party started calling for a "conservative revolution" that would restore traditional values to Poland, and gradually adopted right-wing populist rhetoric characterized by a "somewhat leftist" economical policy to undercut the appeal of far-right anti-capitalist League of Polish Families (LPR), agrarian socialist Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland (Samoobrona) and agrarian Polish People's Party (PSL).[51] The populist pivot of PiS is credited with causing the electoral blowout of Samoobrona and LPR in the 2007 Polish parliamentary election.[52]

Initially, the party was broadly pro-market, although less so than the Civic Platform.[43] It has adopted the social market economy rhetoric similar to that of western European Christian democratic parties.[9] In the 2005 election, the party shifted to the protectionist left on economics.[43] As Prime Minister, Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz was more economically liberal than the Kaczyńskis, advocating a position closer to Civic Platform.[53]

On foreign policy, PiS is Atlanticist and less supportive of European integration than Civic Platform.[43] The party is soft eurosceptic[54][55] and opposes a federal Europe, especially the Euro currency. In its campaigns, it emphasises that the European Union should "benefit Poland and not the other way around".[56] It is a member of the anti-federalist European Conservatives and Reformists Party, having previously been a part of the Alliance for Europe of the Nations and, before that, the European People's Party.[9][57] Although it has some elements of Christian democracy, it is not a Christian democratic party.[58] It is positioned on the right wing of the political spectrum.[59]

Platform

Economy

.jpg/440px-Beata_Szydło_(1).jpg)

The party supports a state-guaranteed minimum social safety net and state intervention in the economy within market economy bounds. During the 2015 election campaign, it proposed tax rebates related to the number of children in a family, as well as a reduction of the VAT rate (while keeping a variation between individual types of VAT rates). In 2019, the lowest personal income tax threshold was decreased from 18% to 17%.[60] Also: a continuation of privatisation with the exclusion of several dozen state companies deemed to be of strategic importance for the country. PiS opposes cutting social welfare spending, and also proposed the introduction of a system of state-guaranteed housing loans. PiS supports state provided universal health care.[61] PiS has been also described as statist,[62][63][64] protectionist,[65][66][67] solidarist,[68] and interventionist.[69] They also hold agrarianist views.[70][71][72][73][74]

National political structures

.jpg/440px-Narodowego_Święto_Niepodległości_(1).jpg)

PiS has presented a project for constitutional reform including, among others: allowing the president the right to pass laws by decree (when prompted to do so by the Cabinet), a reduction of the number of members of the Sejm and Senat, and removal of constitutional bodies overseeing the media and monetary policy. PiS advocates increased criminal penalties. It postulates aggressive anti-corruption measures (including creation of an Anti-Corruption Bureau (CBA), open disclosure of the assets of politicians and important public servants), as well as broad and various measures to smooth the working of public institutions.

PiS is a strong supporter of lustration (lustracja), a verification system created ostensibly to combat the influence of the Communist era security apparatus in Polish society. While current lustration laws require the verification of those who serve in public offices, PiS wants to expand the process to include university professors, lawyers, journalists, managers of large companies, and others performing "public functions". Those found to have collaborated with the security service, according to the party, should be forbidden to practice in their professions.

Diplomacy and defence

The party is in favour of strengthening the Polish Army through diminishing bureaucracy and raising military expenditures, especially for modernisation of army equipment. PiS planned to introduce a fully professional army and end conscription by 2012; in August 2008, compulsory military service was abolished in Poland. It is also in favour of participation of Poland in foreign military missions led by the United Nations, NATO and United States, in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq.

.jpg/440px-V4_Summit_in_Prague_2015-12-03_(23412347901).jpg)

PiS is eurosceptic,[75][76][77] although the party supports integration with the European Union on terms beneficial for Poland. It supports economic integration and tightening cooperation in areas of energy security and military operations, but is sceptical about closer political integration. It is against the formation of a European superstate or federation. PiS is in favour of a strong political and military alliance between Poland and the United States.

In the European Parliament, it is a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists, a group founded in 2009 to challenge the prevailing pro-federalist ethos of the European Parliament and address the perceived democratic deficit existing at a European level.

They have frequently expressed anti-German,[78][79][80] and anti-Russian stances.[81][82][83]

Law and Justice has taken a hardline stance against Russia in its foreign policy since the party's foundation.[84] The party vocally advocated for military aid to Ukraine during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, but announced it would halt arms transfers in September 2023 following disagreements over the export of Ukrainian grain to Poland.[85] The party has been described as divided between pro-Ukrainian and anti-Ukrainian factions.[86]

Though the PiS government initially advocated a pro-Israel policy, relations with Israel deteriorated following the 2018 Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance and subsequent diplomatic incidents.[87] In opposition, PiS called for the expulsion of the Israeli Ambassador following the World Central Kitchen drone strikes and criticized the 2023 Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip.[88]

The PiS government supported accession of Turkey to the European Union.[89] PiS also advocates for a strong relationship with Hungary under Viktor Orbán, though they diverged over the Russo-Ukrainian War.[90][91]

Social policies

The party's views on social issues are much more traditionalist than those of social conservative parties in other European countries,[92][93] and its social views reflect those of the Christian right.[94] PiS has been described to hold right-wing populist views.[102]

Family

The party strongly promotes itself as a pro-family party and encourages married couples to have more children. Prior to 2005 elections, it promised to build three million inexpensive housing units as a way to help young couples start a family. Once in government, it passed legislation lengthening parental leaves.

In 2017, the PiS government commenced the so-called "500+" programme under which all parents residing in Poland receive an unconditional monthly payment of 500 PLN for each second and subsequent child (the 500 PLN support for the first child being linked to income). It also revived the idea of a housing programme based on state-supported construction of inexpensive housing units.

Also in 2017, the party's MPs passed a law that bans most retail trade on Sundays on the premise that workers will supposedly spend more time with their families.

Abortion

The party is anti-abortion and supports further restrictions on Poland's abortion laws which are already one of the most restrictive in Europe. PiS opposes abortion resulting from foetal defects[104] which is currently allowed until specific foetal age.

In 2016, PiS supported legislation to ban abortion under all circumstances, and investigate miscarriages. After the black Protests the legislation was withdrawn.[105]

In October 2020, the Constitutional Court ruled that one of three circumstances (foetal defects) is unconstitutional. However, many constitutionalists argue that this judgement is invalid.

The party is against euthanasia and comprehensive sex education. It has proposed a ban of in-vitro fertilisation.

Disability rights

In April 2018, the PiS government announced a PLN 23 billion (EUR 5.5 billion) programme (named "Accessibility+") aimed at reducing barriers for disabled people, to be implemented 2018–2025.[106][107]

Also in April 2018, parents of disabled adults who required long-term care protested in Sejm over what they considered inadequate state support, in particular, the reduction of support once the child turns 18.[108][109] As a result, the monthly disability benefit for adults was raised by approx. 15 per cent to PLN 1,000 (approx. EUR 240) and certain non-cash benefits were instituted, although protesters' demands of an additional monthly cash benefit were rejected.

Gay rights

The party opposes LGBT rights, in particular same-sex marriages and any other form of legal recognition of same-sex couples. In 2020, Poland was ranked the lowest of any European Union country for LGBT rights by ILGA-Europe.[110] The organisation also highlighted instances of anti-LGBT rhetoric and hate speech by politicians of the ruling party.[111][112] A 2019 survey by Eurobarometer found that more than two-thirds of LGBT people in Poland believe that prejudice against them has risen in the last five years.[113]

On 21 September 2005, PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński said that "homosexuals should not be isolated, however they should not be school teachers for example. Active homosexuals surely not, in any case", but that homosexuals "should not be discriminated otherwise".[114] He has also stated, "The affirmation of homosexuality will lead to the downfall of civilization. We can't agree to it".[115] Lech Kaczyński, while mayor of Warsaw, refused authorisation for a gay pride march; declaring that it would be obscene and offensive to other people's religious beliefs.[116] He stated, "I am not willing to meet perverts."[117] In Bączkowski and Others v. Poland, the European Court of Human Rights unanimously ruled that the ban of the parade violated Articles 11, 13 and 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The judgement stated that "The positive obligation of a State to secure genuine and effective respect for freedom of association and assembly was of particular importance to those with unpopular views or belonging to minorities".[118]

In 2016, Beata Szydło's government disbanded the Council for the Prevention of Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Intolerance, an advisory body set up in 2011 by then-Prime Minister Donald Tusk. The council monitored, advised and coordinated government action against racism, discrimination and hate crime.[119][120]

Many local towns, cities,[121][122] and Voivodeship sejmiks[123] comprising a third of Poland's territory have declared their respective regions as LGBT-free zones with the encouragement of the ruling PiS.[124][121] Polish President Andrzej Duda, who was the Law and Justice party's candidate for presidency in 2015 and 2020, stated that "LGBT is not people, it's an ideology which is worse than Communism."[125][126] During his 2020 successful election campaign, he pledged he would ban teaching about LGBT issues in schools[127] and he proposed changing the constitution to ban LGBT couples from adopting children.[128]

Nationalism

Academic research has characterised Law and Justice as a partially nationalist party,[136] but PiS's leadership rejects this label.[a] Both Kaczyńskis look up for inspirations to the pre-war Sanacja movement with its leader Józef Piłsudski, in contrast to the nationalist Endecja that was led by Piłsudski's political archrival, Roman Dmowski.[140] However, parts of the party, especially the faction around Radio Maryja, are inspired by Dmowski's movement.[141] Polish far-right organisations and parties such as National Revival of Poland, National Movement and Autonomous Nationalists regularly criticise PiS's relative ideological moderation and its politicians for "monopolizing" official political scene by playing on the popular patriotic and religious feelings.[142][143][144] However, the party does include several overtly nationalist politicians in senior positions, such as Digital Affairs Minister Adam Andruszkiewicz, the former leader of the All-Polish Youth;[145] and deputy PiS leader and former Defence Minister Antoni Macierewicz, the founder of the National-Catholic Movement.[146] It has been also described as national-conservative.[147][148][149]

Refugees and economic migrants

PiS opposed the quota system for mass relocation of immigrants proposed by the European Commission to address the 2015 European migrant crisis. This contrasted with the stance of their main political opponents, the Civic Platform, which have signed up to the Commission's proposal.[150] Consequently, in the campaign leading to the 2015 Polish parliamentary election, PiS adopted the discourse typical of the populist-right, linking national security with immigration.[151] Following the election, PiS sometimes utilised Islamophobic rhetoric to rally its supporters.[152]

Examples of anti-migration and anti-Islam comments by PiS politicians when discussing the European migrant crisis:[153] in 2015, Jarosław Kaczyński stated that Poland can not accept any refugees because "they could spread infectious diseases."[154] In 2017, the first Deputy Minister of Justice Patryk Jaki stated that "stopping Islamization is his Westerplatte".[155] In 2017, Interior minister of Poland Mariusz Błaszczak stated that he would like to be called "Charles the Hammer who stopped the Muslim invasion of Europe in the 8th century". In 2017, Deputy Speaker of the Sejm Joachim Brudziński stated during the pro-party rally in Siedlce; "if not for us (PiS), they (Muslims) would have built mosques in here (Poland)."[156]

Structure

Internal factions

Law and Justice is divided into many internal factions, but they can be grouped into three main blocs.[162]

The most influential group within PiS is unofficially named "Order of the Centre Agreement". It is led by leader is Jarosław Kaczyński, and its main members are Joachim Brudziński, Adam Lipiński and Mariusz Błaszczak.

The second major group is a radical, religious and hard Eurosceptic right-wing faction focused around Antoni Macierewicz, Beata Szydło that has close views to United Poland party of Zbigniew Ziobro. This faction opts for radical reforms and is supported by Jacek Kurski and Tadeusz Rydzyk.

The third major group is a Christian-democratic, republican and moderate social conservative faction focused around Mateusz Morawiecki, Łukasz Szumowski, Jacek Czaputowicz that has close views to The Republicans party of Adam Bielan. Although not officially a party member, Polish president Andrzej Duda can also be placed in this faction.

Political committee

President:

Vice-Presidents:

Treasurer:

- Teresa Schubert

'Spokesperson':

- Anita Czerwińska

Party discipline spokesman:

Chairman of the Executive Committee:

President of the Parliamentary Club:

Leadership

| No. | Image | Name | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

|

Lech Kaczyński | 13 June 2001 – 18 January 2003 |

| 2. | .JPG/440px-Jarosław_Kaczyński_Sejm_2016a_(cropped).JPG)

|

Jarosław Kaczyński | 18 January 2003 Incumbent |

Election results

Sejm

| Election year | Leader | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Lech Kaczyński | 1,236,787 | 9.5 (#4) | 44 / 460

|

SLD–UP–PSL (2001-2003) | |

| SLD–UP Minority (2003-2004) | ||||||

| SLD-UP-SDPL Minority (2004-2005) | ||||||

| 2005 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 3,185,714 | 27.0 (#1) | 155 / 460

|

PiS Minority (2005-2006) | |

| PiS–SRP–LPR | ||||||

| PiS Minority (2007) | ||||||

| 2007 | 5,183,477 | 32.1 (#2) | 166 / 460

|

PO–PSL | ||

| 2011 | 4,295,016 | 29.9 (#2) | 157 / 460

|

PO–PSL | ||

| 2015 | 5,711,687 | 37.6 (#1) | 193 / 460

|

PiS | ||

| As a part of the United Right coalition, which won 235 seats in total.[163] | ||||||

| 2019 | 8,051,935 | 43.6 (#1) | 187 / 460

|

PiS | ||

| As a part of the United Right coalition, which won 235 seats in total. | ||||||

| 2023 | 7,640,854 | 35.4 (#1) | 165 / 460

|

KO–PL2050–KP–NL | ||

| As a part of the United Right coalition, which won 194 seats in total. | ||||||

Senate

| Election year | # of overall seats won |

+/– | Majority |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 0 / 100

|

Opposition | |

| As part of the Senate 2001 coalition, which won 15 seats. | |||

| 2005 | 49 / 100

|

Coalition | |

| 2007 | 39 / 100

|

Opposition | |

| 2011 | 31 / 100

|

Opposition | |

| 2015 | 61 / 100

|

PiS | |

| 2019 | 38 / 100

|

Opposition | |

| As part of the United Right coalition, which won 48 seats. | |||

| 2023 | 29 / 100

|

Opposition | |

| As part of the United Right coalition, which won 34 seats. | |||

European Parliament

| Election year | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 771,858 | 12.7 (#3) | 7 / 54

|

|

| 2009 | 2,017,607 | 27.4 (#2) | 15 / 50

|

|

| 2014 | 2,246,870 | 31.8 (#2) | 19 / 51 *

|

|

| 2019 | 6,192,780 | 45.38 (#1) | 27 / 51 *

|

*Currently 16: Zdzisław Krasnodębski is elected from the PiS register, but not a member of the party, Mirosław Piotrowski left PiS (08.10.2014), Marek Jurek is a member of Right Wing of the Republic.

Presidential

| Election year | Candidate | 1st round | 2nd round | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of overall votes | % of overall vote | # of overall votes | % of overall vote | ||

| 2005 | Lech Kaczyński | 4,947,927 | 33.1 (#2) | 8,257,468 | 54.0 (#1) |

| 2010 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 6,128,255 | 36.5 (#2) | 7,919,134 | 47.0 (#2) |

| 2015 | Andrzej Duda | 5,179,092 | 34.8 (#1) | 8,719,281 | 51.5 (#1) |

| 2020 | Supported Andrzej Duda | 8,450,513 | 43.50 (#1) | 10,440,648 | 51.03% (#1) |

Regional assemblies

| Election year | % of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 12.1 (#4) | 79 / 561

| ||||

| In coalition with Civic Platform as POPiS. | ||||||

| 2006 | 25.1 (#2) | 170 / 561

|

||||

| 2010 | 23.1 (#2) | 141 / 561

|

||||

| 2014 | 26.9 (#1) | 171 / 555

|

||||

| 2018 | 34.1 (#1) | 254 / 552

|

||||

| 2024 | 34.3 (#1) | 239 / 552

|

||||

County councils

| Election year | % of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | no data | 0 / 6,294

|

|

| 2006 | 19.8 (#1) | 1,242 / 6,284

|

|

| 2010 | 17.3 (#2) | 1,085 / 6,290

|

|

| 2014 | 23.5 (#1) | 1,514 / 6,276

|

|

| 2018 | 30.5 (#1) | 2,114 / 6,244

|

|

| 2024 | 30.0 (#1) | 2,080 / 6,170

|

Mayors

| Election | No. | Change |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2 | |

| 2006 | 77 | |

| 2010 | 37 | |

| 2014 | 124 | |

| 2018 | 234 |

Presidents of the Republic of Poland

| Name | Image | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lech Kaczyński |

|

23 December 2005 | 10 April 2010 |

| Andrzej Duda |

|

6 August 2015 | incumbent |

Prime Ministers of the Republic of Poland

| Name | Image | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz | _cropped.jpg/440px-Kazimierz_Marcinkiewicz_(1118622297)_cropped.jpg)

|

31 October 2005 | 14 July 2006 |

| Jarosław Kaczyński | _(cropped_2).jpg/440px-Jarosław_Kaczyński_(5)_(cropped_2).jpg)

|

14 July 2006 | 16 November 2007 |

| Beata Szydło | .jpg/440px-Beata_Szydło_-_Tallinn_Digital_Summit_2017_(cropped_3).jpg)

|

16 November 2015 | 11 December 2017 |

| Mateusz Morawiecki | .jpg/440px-Mateusz_Morawiecki_Prezes_Rady_Ministrów_(cropped).jpg)

|

11 December 2017 | 13 December 2023 |

Voivodeship Marshals

| Name | Image | Voivodeship | Date vocation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grzegorz Schreiber |

|

Łódź Voivodeship | 22 November 2018 |

| Jarosław Stawiarski |

|

Lublin Voivodeship | 21 November 2018 |

| Władysław Ortyl |

|

Podkarpackie Voivodeship | 27 May 2013 |

| Andrzej Bętkowski |

|

Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship | 22 November 2018 |

| Witold Kozłowski |

|

Lesser Poland Voivodeship | 19 November 2018 |

| Artur Kosicki |

|

Podlaskie Voivodeship | 11 December 2018 |

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ During the 2008 Polish Independence Day celebrations, Lech Kaczyński said in his speech during the visit to the city of Elbląg that "the state is a great value, and attachment to the state, to one's fatherland, we call patriotism – beware of the word nationalism, as nationalism is evil!"[137] On the same day during the celebrations in Warsaw, L. Kaczyński again stated: "patriotism doesn't equal nationalism."[138] In 2011, Jarosław Kaczyński criticised pre-war Polish nationalism for "its intellectual, political and moral failure" by emphasising that the movement "did not know how to deal with and solve the problems of Polish minorities."[139]

Citations

- ^ "Historia PiS". e-sochaczew.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Drabik, Piotr (1 June 2023). "PiS nie jest największą partią w Polsce. "Liczy się tylko kartel czterech"". Radio ZET (in Polish).

Drugie miejsce należy do Prawa i Sprawiedliwości, które przez 22 lata istnienia mocno ugruntowało się także w terenie. Sekretarz generalny partii Krzysztof Sobolewski przekazał nam, że ugrupowanie rządzące ma ok. 48 tys. członków. - Najwięcej w województwie mazowieckim - dodał. Na pytanie, jak liczebność PiS zmieniła się w ostatnich trzech latach, odpowiedział tylko: - Znacząco wzrosła.

[Second place belongs to Law and Justice, which has also become firmly established on the ground over its 22 years of existence. The party's general secretary Krzysztof Sobolewski told us that the ruling grouping has around 48,000 members. - The largest number in the Mazowieckie Voivodeship," he added. When asked how the size of PiS had changed in the last three years, he replied only: - It has increased significantly.] - ^ Fijołek, Marcin (2012). "Republikańska symbolika w logotypie partii politycznej Prawo i Sprawiedliwość". Ekonomia I Nauki Humanistyczne (19): 9–17. doi:10.7862/rz.2012.einh.23.

- ^ "Premier o PiS. "Myśl socjalistyczna również jest dla nas ważna"". Wirtualna Polska (in Polish). 21 July 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Turczyn, Andrzej (22 July 2019). "Mateusz Morawiecki: robotnicza myśl socjalistyczna jest głęboko obecna w filozofii Prawa i Sprawiedliwości". Trybun Broni Palnej (in Polish). Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Szeląg, Wojciech (24 May 2021). "Marek Goliszewski, prezes BCC: Polski Ład wystraszył nawet tych, którzy wspierają PiS". Interia (in Polish). Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Kołakowska, Agnieszka (9 October 2019). "In defense of Poland's ruling party". Politico. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Orenstein, Mitchell (4 July 2018). "Populism with socialist characteristics". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bale, Tim; Szczerbiak, Aleks (December 2006). "Why is there no Christian Democracy in Poland (and why does this matter)?". SEI Working Paper (91). Sussex European Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Santora, Marc (14 October 2019). "In Poland, Nationalism With a Progressive Touch Wins Voters (Published 2019)". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Nordsieck, Wolfram (5 June 2019). Parties and Elections in Europe: Parliamentary Elections and Governments since 1945, European Parliament Elections, Political Orientation and History of Parties. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 9783732292509.

- ^ Licia Cianetti; James Dawson; Seán Hanley (2018). "Rethinking "democratic backsliding" in Central and Eastern Europe – looking beyond Hungary and Poland". East European Politics. 34 (3): 243–256. doi:10.1080/21599165.2018.1491401.

Over the past decade, a scholarly consensus has emerged that that democracy in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is deteriorating, a trend often subsumed under the label 'backsliding'. ... the new dynamics of backsliding are best illustrated by the one-time democratic front-runners Hungary and Poland.

</ref/>- Piotrowski, Grzegorz (2020). "Civil Society in Illiberal Democracy: The Case of Poland". Politologický časopis – Czech Journal of Political Science. XXVII (2): 196–214. doi:10.5817/PC2020-2-196. ISSN 1211-3247. S2CID 226544116.

- Sata, Robert; Karolewski, Ireneusz Pawel (2020). "Caesarean politics in Hungary and Poland". East European Politics. 36 (2): 206–225. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1703694. hdl:20.500.14018/13975. S2CID 213911605.

- Drinóczi, Tímea; Bień-Kacała, Agnieszka (2019). "Illiberal Constitutionalism: The Case of Hungary and Poland". German Law Journal. 20 (8): 1140–1166. doi:10.1017/glj.2019.83.

- Ágh, Attila (2019). Declining Democracy in East-Central Europe: The Divide in the EU and Emerging Hard Populism. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1-78897-473-8.

- Sadurski, Wojciech (2019). "Illiberal Democracy or Populist Authoritarianism?". Poland's Constitutional Breakdown. Oxford University Press. pp. 242–266. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198840503.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-884050-3.

- Lendvai-Bainton, Noemi; Szelewa, Dorota (2020). "Governing new authoritarianism: Populism, nationalism and radical welfare reforms in Hungary and Poland". Social Policy & Administration. 55 (4): 559–572. doi:10.1111/spol.12642.

- Fomina, Joanna; Kucharczyk, Jacek (2016). "Populism and Protest in Poland". Journal of Democracy. 27 (4): 58–68. doi:10.1353/jod.2016.0062. S2CID 152254870.

The 2015 victory of Poland's Law and Justice (PiS) party is an example of the rise of contemporary authoritarian populism... the PiS gained a parliamentary absolute majority; it has since drawn on this majority to dismantle democratic checks and balances. The PiS's policies have led to intensifying xenophobia, aggressive nationalism, and unprecedented polarisation that have engendered deep splits within Polish society and have given rise to social protest movements not seen in Poland since 1989.

- Markowski, Radoslaw (2019). "Creating Authoritarian Clientelism: Poland After 2015". Hague Journal on the Rule of Law. 11 (1): 111–132. doi:10.1007/s40803-018-0082-5. ISSN 1876-4053. S2CID 158160832.

- ^ "Poland Ousts Government as Law & Justice Gains Historic Majority". Bloomberg. 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Poland elections: Conservatives secure decisive win". 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Przyjdzie dzień, że w Warszawie będzie Budapeszt". tvn24.pl. 9 October 2011.

- ^ Karolewski, Ireneusz Paweł (2016). "Protest and participation in post-transformation Poland: The case of the Committee for the Defense of Democracy (KOD)". Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 49 (3): 255–267. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2016.06.003.

- ^ "EU and Poland edge closer to showdown over judicial reform". Financial Times. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Koper, Pawel; Sobczak, Anna. "Polish president backs down in judicial reform spat". Reuters.

- ^ "The Observer view on Poland's assault on law and the judiciary". The Guardian. 22 July 2017.

- ^ "How Poland's government is weakening democracy". The Economist.

- ^ Marcinkiewicz, Kamil; Stegmaier, Mary (21 July 2017). "Poland appears to be dismantling its own hard-won democracy". The Washington Post.

- ^ [17][18][19][20][21]

- ^ "Chronology: Poland clashes with EU over judicial reforms, rule of law". Reuters. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Moberg, Andreas (2020). "When the Return of the Nation-State Undermines the Rule of Law: Poland, the EU, and Article 7 TEU". The European Union and the Return of the Nation State: Interdisciplinary European Studies. Springer International Publishing. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-3-030-35005-5.

- ^ Sadurski, Wojciech (2019). Poland's Constitutional Breakdown. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884050-3.

- ^ a b c Tworzecki, Hubert (2019). "Poland: A Case of Top-Down Polarization". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 681 (1): 97–119. doi:10.1177/0002716218809322. S2CID 149662184.

Lacking the two-thirds of majority needed to change the constitution outright, as Hungary's government had done several years earlier, PiS sought to accomplish the same goal through ordinary legislation. When the Constitutional Tribunal objected, its rulings were ignored until it could be packed with government supporters, some of whom were sworn in by the president—a strong partisan of PiS himself, who made no effort to stand in the government's way—in a rushed, middle-of-the-night ceremony. The national legislature was likewise turned into a rubber-stamp body through routine side-stepping of parliamentary procedure.

- ^ Lendvai-Bainton, Noemi; Szelewa, Dorota (2020). "Governing new authoritarianism: Populism, nationalism and radical welfare reforms in Hungary and Poland". Social Policy & Administration. 55 (4): 559–572. doi:10.1111/spol.12642.

- ^ Zawadzka, Z (17 December 2018). "Polish Productions about Polish Problems". In Robson, Peter; Schulz, Jennifer L. (eds.). Ethnicity, Gender, and Diversity: Law and Justice on TV. Lexington Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4985-7291-0.

On January 7, 2016, the amendment of the Radio and Television Act of December 29, 1992 was signed into law, enabling the conservative government to control the state media.

; "Poland". RSF. Reporters without borders. Retrieved 27 September 2020.Partisan discourse and hate speech are still the rule within state-owned media, which have been transformed into government propaganda mouthpieces. Their new directors tolerate neither opposition nor neutrality from employees and fire those who refuse to comply.

; Surowiec, Paweł; Kania-Lundholm, Magdalena; Winiarska-Brodowska, Małgorzata (2020). "Towards illiberal conditioning? New politics of media regulations in Poland (2015–2018)". East European Politics. 36 (1): 27–43. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1608826. S2CID 164430720. - ^ Piotrowski, Grzegorz (2020). "Civil Society in Illiberal Democracy: The Case of Poland". Politologický časopis – Czech Journal of Political Science. XXVII (2): 196–214. doi:10.5817/PC2020-2-196. ISSN 1211-3247. S2CID 226544116.

- ^ Sata, Robert; Karolewski, Ireneusz Pawel (2020). "Caesarean politics in Hungary and Poland". East European Politics. 36 (2): 206–225. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1703694. hdl:20.500.14018/13975. S2CID 213911605.

- ^ Sadurski 2019, Illiberal Democracy or Populist Authoritarianism?.

- ^ Ágh, Attila (2019). Declining Democracy in East-Central Europe: The Divide in the EU and Emerging Hard Populism. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1-78897-473-8.

- ^ Wyniki wyborów 2019 do Sejmu RP, retrieved 3 October 2022

- ^ Wyniki wyborów 2019 do Senatu RP, retrieved 3 October 2022

- ^ Barteczko, Agnieszka; Krajewski, Adrian (26 October 2015). "Outright majority for Polish eurosceptics hangs in balance". Reuters. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Law and Justice breakaway politicians form new 'association', thenews.pl

- ^ Conservatives' EU alliance in turmoil as Michał Kamiński leaves 'far right' party, The Guardian, 22 November 2010

- ^ "Opposition party Law and Justice expels critics". Polskie Radio. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Conservative MPs form 'Poland United' breakaway group after dismissals". TheNews.pl. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "MPs axed by Law and Justice opposition". TheNews.pl. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "New Polish conservative party launched". TheNews.pl. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Myant et al. (2008), p. 3

- ^ a b c d Tiersky, Ronald; Jones, Erik (2007). Europe Today: a Twenty-first Century Introduction. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-7425-5501-3.

- ^ Frank Jacobs, "Zombie Borders", The New York Times Opinionator blog, 12 December 2011

- ^ Jungerstam-Mulders (2006), p. 104

- ^ Jungerstam-Mulders (2006), p. 103

- ^ Folvarčný, Adam; Kopeček, Lubomír (2020). "Which conservatism? The identity of the Polish Law and Justice party". Politics in Central Europe. 16 (1): 180. doi:10.2478/pce-2020-0008. ISSN 1801-3422.

- ^ Immigration and Nationality Directorate (April 2002). "Poland: Country Assessment". United Kingdom: Home Office. p. 7.

- ^ Nikolaus Werz [in German] (30 April 2003). Populismus: Populisten in Übersee und Europa. Analysen. Vol. 79 (1 ed.). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften Wiesbaden. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-3-663-11110-8.

- ^ "Poland digs in against tide toward secularism". Chicago Tribune. 23 May 2006.

- ^ Krzysztof Kowalczyk; Jerzy Sielski (2006). Partie i ugrupowania parlamentarne III Rzeczypospolitej (in Polish). Dom Wydawniczy DUET. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-83-89706-84-3.

- ^ Seongcheol Kim (2022). Discourse, Hegemony, and Populism in the Visegrád Four. Routledge Studies in Extremism and Democracy. Routledge. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-1-003-18600-7.

- ^ Myant et al. (2008), pp. 67–68

- ^ Myant et al. (2008), p. 88

- ^ Szczerbiak, Aleks; Taggart, Paul A. (2008). Opposing Europe?. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-925830-7.

- ^ Maier et al. (2006), p. 374

- ^ Jungerstam-Mulders (2006), p. 100

- ^ Sozańska, Dominika. "Chrześcijańska demokracja w Polsce" (PDF). core.ac.uk (in Polish). Krakow Academy.

- ^

- Michael Minkenberg (2013). "Between Tradition and Transition: the Central European Radical Right and the New European Order". In Christina Schori Liang (ed.). Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-4094-9825-4.

- Lenka Bustikova (2018). "The Radical Right in Eastern Europe". In Jens Rydgren (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford University Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-19-027455-9.

- Aleks Szczerbiak (2012). Poland Within the European Union: New Awkward Partner Or New Heart of Europe?. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-38073-7.

- ^ "Favourable tax changes included in the Polish Deal – the Prime Minister took part in a videoconference with entrepreneurs - The Chancellery of the Prime Minister - Gov.pl website". The Chancellery of the Prime Minister. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "PiS wygrywa: koniec NFZ, system budżetowy i sieć szpitali? – Polityka zdrowotna". www.rynekzdrowia.pl. 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Wyborcza.pl". wyborcza.pl.

- ^ "Petru: Muzealny etatyzm PiS". www.rp.pl.

- ^ Kowalski, Radosław (20 November 2015). "Ziemkiewicz krytykuje PiS za etatyzm". Nasze Miasto.

- ^ "Program działań Prawa i Sprawiedliwości. Tworzenie szans dla wszystkich". Instytut Sobieskiego. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Dossier: What PiS would change in the economy". Polityka Insight. PI Research. October 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Elliott, Dominic (26 October 2015). "Poland's tilt to nationalism is bad for investment". Archived from the original on 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Marcinkiewicz: Program PiS to przywrócenie solidaryzmu, także w służbie zdrowia". pb.pl. Plus Biznesu. 6 October 2005.

- ^ "To łączy rządy PiS z polityką Herberta Hoovera i Franklina D. Roosevelta". businessinsider.com.pl (in Polish). Business Insider. 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Antoni Macierewicz: Wieś jest w centrum programy PiS" [Antoni Macierewicz: Polish countryside is at the center of the PiS program]. Polskie Radio 24 (in Polish). 6 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Joanna Solska (6 April 2019). "Konwencja rolnicza w Kadzidle. PiS znów stawia na wieś" [Agricultural Convention in Kadzidło. PiS again puts on the countryside]. Polityka (in Polish). Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ SJ, MNIE (26 May 2019). "PiS wygrywa na wsi. KE w miastach" [PiS has won in the countryside. KE in cities]. TVPinfo (in Polish).

- ^ Stijn van Kessel (2015). Populist Parties in Europe: Agents of Discontent?. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-137-41411-3.

- ^ Łukasz Warzecha (20 April 2018). "PiS, Czyli Populizm i Socjalizm" [PiS means Populism and Socialism] (in Polish). Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ Vasilopoulou, Sofia (2018). "The Radical Right and Euroskepticism". In Rydgren, Jens (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-027455-9.

- ^ Guerra, Simona (2020). "The Historical Roots of Euroscepticism in Poland". Euroscepticisms: The Historical Roots of a Political Challenge. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-42125-7.

- ^ Lázár, Nóra (2015). "Euroscepticism in Hungary and Poland: a Comparative Analysis of Jobbik and the Law and Justice Parties". Politeja – Pismo Wydziału Studiów Międzynarodowych i Politycznych Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. 12 (33): 215–233. doi:10.12797/Politeja.12.2015.33.11. ISSN 1733-6716.

- ^ Wieliński, Bartosz T. (8 June 2018). "Poland, Germany still friends despite PiS' anti-German campaign". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Sieradzka, Monika (11 July 2020). "Anti-German sentiment colors Polish president's election campaign". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Zaborowski, Marcin (27 November 2017). "What is the Future for German-Polish Relations". Visegrad Insight. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Poland's New Populism". Foreign Policy. 5 October 2018.

- ^ "Russia warns Poland not to touch Soviet WW2 memorials". BBC News. 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Law and Justice banks on Smolensk conspiracy theories". Euractiv. 13 April 2016.

- ^ "Why Is CPAC Traveling to Illiberal Hungary?". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ https://edition.cnn.com/2023/09/21/europe/poland-ukraine-weapons-grain-explainer-intl/index.html

- ^ https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2023/10/06/ahead-of-poland-election-support-for-ukraine-is-a-collateral-victim_6153496_4.html

- ^ https://www.euractiv.pl/section/polityka-zagraniczna-ue/news/polski-premier-nie-przyjedzie-na-szczyt-v4-do-jerozolimy/

- ^ https://wpolityce.pl/polityka/687426-wydalenie-ambasadora-izraela-prezes-pis-zrobilbym-to

- ^ https://www.newarab.com/analysis/whats-behind-turkey-and-polands-growing-alliance

- ^ https://vsquare.org/orban-kaczynski-novak-morawiecki-poland-hungary-russia-war-ukraine/

- ^ https://notesfrompoland.com/2024/02/01/pis-open-to-orban-joining-its-european-group-and-condemns-eu-blackmail-against-hungary/

- ^ Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "Poland". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Why is Poland's government worrying the EU? The Economist. Published 12 January 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "Family, faith, flag: the religious right and the battle for Poland's soul". The Guardian. 5 October 2019.

- ^ "EU takes Poland to court over judicial crackdown". Axios. 24 September 2018.

- ^ "European Court of Justice orders Poland to stop purging its supreme court judges". The Independent. 19 October 2018.

- ^ "After Loss in Austria, a Look at Europe's Right-wing Parties". Haaretz. 24 May 2016.

- ^ Henceroth, Nathan (2019). "Open Society Foundations". In Ainsworth, Scott H.; Harward, Brian M. (eds.). Political Groups, Parties, and Organizations that Shaped America. ABC-CLIO. p. 739.

- ^ Krzyżanowska, Natalia; Krzyżanowski, Michał (2018). "'Crisis' and Migration in Poland: Discursive Shifts, Anti-Pluralism and the Politicisation of Exclusion". Sociology. 52 (3): 612–618. doi:10.1177/0038038518757952. S2CID 149501422.

- ^ Dudzińska, Agnieszka; Kotnarowski, Michał (24 July 2019). "Imaginary Muslims: How the Polish right frames Islam". brookings.edu. Brookings.

- ^ Henceroth, Nathan (2019). "Open Society Foundations". In Ainsworth, Scott H.; Harward, Brian M. (eds.). Political Groups, Parties, and Organizations that Shaped America. ABC-CLIO. p. 739.

- ^ [95][96][97][98][99][100][101]

- ^ "Protests over Abortion Ruling Widen, Radicalise and Threaten Polish Government". Balkan Insight. 26 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Jarosław Kaczyński o aborcji. Dzieci z zespołem Downa muszą żyć". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). 14 October 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Walker, Shaun; Strek, Kasia (23 October 2020). "The price of choice – the fight over abortion in Poland | photo essay". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Inauguracja Programu Dostępność Plus 2018–2025" (in Polish). Ministerstwo Inwestycji i Rozwoju. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "PiS przeznaczy 23 mld zł na program "Dostępność Plus"". Business Insider (in Polish). 17 July 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Protest of disabled persons in the Sejm – communique from the Sejm Information Centre for the foreign media" (in Polish). Sejm. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Parents of disabled children occupy Poland's parliament". Deutsche Welle. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Poland's culture war: LGBT people forced to turn to civil disobedience". euronews. 6 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ ANNUAL REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANS, AND INTERSEX PEOPLE IN POLAND COVERING THE PERIOD OF JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2019 ILGA-Europe

- ^ Fitzsimons, Tim. "Anti-gay hate on the rise in parts of Europe, report finds". NBC News. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020). EU LGBTI II: A long way to go for LGBTI equality (PDF). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. doi:10.2811/7746. ISBN 978-92-9474-997-0.

- ^ Wiadomosci, PL.

- ^ "Polish election", Gay mundo, The gully.

- ^ "Poland: LGBT rights under attack". Amnesty International. Retrieved on 19 July 2009.

- ^ "Poland: Official Homophobia Threatens Basic Freedoms". Human Rights Watch. 4 June 2006.

- ^ Bączkowski and Others v. Poland

- ^ "Polish PM abolishes anti-discrimination council". Radio Poland. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Lidia; Justyna, Pawlak (3 January 2018). "Poland's far-right: opportunity and threat for ruling PiS". Reuters. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ a b Polish towns advocate ‘LGBT-free’ zones while the ruling party cheers them on, Washington Post, 21 July 2019

- ^ Why 'LGBT-free zones' are on the rise in Poland, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 27 July 2019

- ^ Polish ruling party whips up LGBTQ hatred ahead of elections amid 'gay-free' zones and Pride march attacks, Telegraph, 9 August 2019

- ^ Ciobanu, Claudia (25 February 2020). "A Third of Poland Declared 'LGBT-Free Zone'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Gera, Vanessa (13 June 2020). "Polish president calls LGBT 'ideology' worse than communism". AP NEWS. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Polish president revives attacks on LGBT community in re-election campaign". The Irish Times. 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Polish president says he would ban LGBT teaching in schools". Reuters. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Polish president proposes constitutional ban on gay adoption". NBC News. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Charnysh, Volha (18 December 2017). "The Rise of Poland's Far Right". Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Traub, James (2 November 2016). "The Party That Wants to Make Poland Great Again". The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Adekoya, Remi (25 October 2016). "Xenophobic, authoritarian – and generous on welfare: how Poland's right rules". The Guardian.

- ^ "Protests grow against Poland's nationalist government". The Economist. 20 December 2016.

- ^ Polynczuk-Alenius, Kinga (2020). "At the intersection of racism and nationalism: Theorising and contextualising the 'anti-immigration' discourse in Poland". Nations and Nationalism. 27 (3): 766–781. doi:10.1111/nana.12611.

- ^ Krzyżanowski, Michał (2018). "Discursive Shifts in Ethno-Nationalist Politics: On Politicization and Mediatization of the "Refugee Crisis" in Poland". Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 16 (1–2): 76–96. doi:10.1080/15562948.2017.1317897. S2CID 54068132.

- ^ Żuk, Piotr (2018). "Nation, national remembrance, and education — Polish schools as factories of nationalism and prejudice". Nationalities Papers. 46 (6): 1046–1062. doi:10.1080/00905992.2017.1381079. S2CID 158161859.

- ^ [129][130][131][132][133][134][135]

- ^ S.A., Wirtualna Polska Media (30 September 2008). "Prezydent L. Kaczyński: nacjonalizm jest złem".

- ^ IAR (11 November 2008). "Lech Kaczyński: Patriotyzm nie oznacza nacjonalizmu".

- ^ "Jarosław Kaczyński z Romana Dmowskiego". www.rp.pl.

- ^ "Kowal: Kaczyński powstrzymuje w Polsce nacjonalizm". Kresy – Portal Społeczności Kresowej. 10 February 2016.

- ^ Żuk, Piotr; Żuk, Paweł (2019). "Dangerous Liaisons between the Catholic Church and State: the religious and political alliance of the nationalist right with the conservative Church in Poland". Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe. 27 (2–3): 191–212. doi:10.1080/25739638.2019.1692519. S2CID 211393866.

- ^ "Search Result | AUTONOM.PL | autonomiczni nacjonaliści nowoczesny nacjonalizm AN". autonom.pl.

- ^ ""Prawo I Sprawiedliwość" | Nacjonalista.pl – Dziennik Narodowo-Radykalny". nacjonalista.pl.

- ^ "Wyniki wyszukiwania dla ""Prawo i Sprawiedliwość"" – Xportal.pl".

- ^ "Far-right Polish official steps back from radical comments". Seattle Times. 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Polish minister accused of having links with pro-Kremlin far-right groups". The Guardian. 12 July 2017.

- ^ Hloušek, Vít; Kopeček, Lubomír (2010), Origin, Ideology and Transformation of Political Parties: East-Central and Western Europe Compared, Ashgate, p. 196

- ^ Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "Poland". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "How the Catholic Church ties in to Poland's judicial reform". dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 24 July 2017.

- ^ Bachman, Bart (15 June 2016). "Diminishing Solidarity: Polish Attitudes toward the European Migration and Refugee Crisis". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ The Everyday Politics of Migration Crisis in Poland: Between Nationalism, Fear and Emphathy, Palgrave Macmillan, Krzysztof Jaskulowski, 2019, pages 38–45

- ^ Jaskulowski, Krzysztof; Pawlak, Marek (11 April 2019). "Migration and Lived Experiences of Racism: The Case of High-Skilled Migrants in Wrocław, Poland". International Migration Review. 54 (2): 447–470. doi:10.1177/0197918319839947.

- ^ Wyborcza, Adam Leszczyński of Gazeta (2 July 2015). "'Poles don't want immigrants. They don't understand them, don't like them'". The Guardian.

- ^ "Polish opposition warns refugees could spread infectious diseases". Reuters. 15 October 2015.

- ^ "Kto chce zakazać Koranu w Polsce". www.rp.pl.

- ^ "W Siedlcach wiec poparcia dla rządu PiS". 9 September 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Głowacki, Witold (15 December 2017). "Frakcje w PiS. Jarosław Kaczyński, Andrzej Duda, Mateusz Morawiecki... jakie są grupy interesu w PiS?". Polska Times.

- ^ "W PiS wrze! Za kulisami toczą się wewnętrzne wojenki. Kto z kim się gryzie?". Fakt24.pl. 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Wojny PiSowskich frakcji". 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Wojna w PiS o wybory prezydenckie. Czy Morawiecki szkodzi Dudzie? [ANALIZA]". Onet Wiadomości. 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Wraca wojna Ziobry z Morawieckim. PiS dociśnie pedał gazu [ANALIZA]". Onet Wiadomości. 22 July 2020.

- ^ [157][158][159][160][161]

- ^ "Offer to sell domain: prawapolityka.pl". www.aftermarket.pl.

General references

- Jungerstam-Mulders, Susanne (2006). Post-Communist EU Member States: Parties and Party Systems. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4712-6.

- Maier, Michaela; Tenscher, Jens (2004). Campaigning in Europe – Campaigning for Europe. Münster: LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-9322-4.

- Myant, Martin R.; Cox, Terry (2008). Reinventing Poland: Economic and Political Transformation and Evolving National Identity. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45175-8.

External links

- Official website