King of the Four Corners

King of the Four Corners of the World (Sumerian: lugal-an-ub-da-limmu-ba,[1] Akkadian: šarru kibrat arbaim,[2] šar kibrāti arbaʾi,[3] or šar kibrāt erbetti[4]), alternatively translated as King of the Four Quarters of the World, King of the Heaven's Four Corners or King of the Four Corners of the Universe[5] and often shortened to simply King of the Four Corners,[3][6] was a title of great prestige claimed by powerful monarchs in ancient Mesopotamia. Though the term "four corners of the world" does refer to specific geographical places within and near Mesopotamia itself, these places were (at the time the title was first used) thought to represent locations near the actual edges of the world and as such, the title should be interpreted as something equivalent to "King of all the known world", a claim to universal rule over the entire world and everything within it.

The title was first used by Naram-Sin of the Akkadian Empire in the 23rd century BC and was later used by the rulers of the Neo-Sumerian Empire, after which it fell into disuse. It was revived as a title by a number of Assyrian rulers, becoming especially prominent during the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The final ruler to claim the title was the first Persian Achaemenid king, Cyrus the Great, after his conquest of Babylon in 539 BC.

It is possible, at least among Assyrian rulers, that the title of King of the Four Corners was not inherited through normal means. As the title is not attested for all Neo-Assyrian kings and for some only attested several years into their reign it is possible that it might have had to be earned by each king individually, possibly through completing successful military campaigns in all four points of the compass. The similar title of šar kiššatim ("King of Everything" or "King of the Universe"), also with Akkadian origins and attested for some of the Neo-Assyrian kings, may have required seven successful military campaigns. The difference between the exact meaning of the two titles may have been that "King of the Universe" laid claim to the cosmological realm whereas "King of the Four Corners of the World" laid claim to the terrestrial.

Meaning of "Four Corners of the World"

The term "four corners of the world" appears in several ancient mythologies and cosmologies, wherein it roughly corresponds the four points of the compass. In most of these representations, four principal rivers run to these four corners, their water irrigating the four quadrants (or quarters) of the world. In the view of the Mesopotamian Akkadians, the term referred to four regions on the edge of the then known world; Subartu (probably corresponding to the region of Assyria) in the north, Martu (roughly corresponding to modern Syria) in the west, Elam in the east and Sumer in the south.[10] To Naram-Sin of Akkad (r. 2254–2218 BC), the creator of the title, it probably, in geographical terms, expressed his dominion over the regions Elam, Subartu, Amurru and Akkad (representing east, north, west and south respectively).[11]

The term thus covers a somewhat clear geographical region, corresponding to Mesopotamia and its surroundings, but should be understood as referring to the entire known world. At the point in time when the title was first used, the 2200s BC, the Mesopotamians would have equated all of Mesopotamia to the entire world; the region was highly productive, densely populated and was bordered on all sides by seemingly empty and uninhabited lands.[12] A title the like of King of the Four Corners of the World should be taken as meaning that its holder was the ruler of the entire Earth and everything within it.[5] The title can be interpreted as being equivalent to calling oneself "King of all the known world".[6] Thus, the title is an example of merism, combining contrasting concepts to refer to an entirety (the four corners being on the edges of the world and the title referring to them and everything in between).[13]

History

Background (2900–2334 BC)

During the Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia (c. 2900–2350 BC), the rulers of the various city-states in the region would often launch invasions into regions and cities far from their own, at most times with negligible consequences for themselves, in order to establish temporary and small empires to either gain of keep a superior position relative to the other city-states. This early empire-building was encouraged as the most powerful monarchs were often rewarded with the most prestigious titles, such as the title of lugal (literally "big man" but often interpreted as "king", probably with military connotations[n 1]). Most of these early rulers had probably acquired these titles rather than inherited them.[12]

Eventually this quest to be more prestigious and powerful than the other city-states resulted in a general ambition for universal rule. Since Mesopotamia was equated to correspond to the entire world and Sumerian cities had been built far and wide (cities the like of Susa, Mari and Assur were located near the perceived corners of the world) it seemed possible to reach the edges of the world (at this time thought to be the lower sea, the Persian gulf, and the upper sea, the Mediterranean).[12]

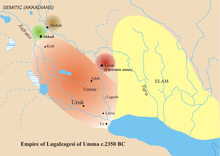

Rulers attempting to reach a position of universal rule became more common during the Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2450–2350 BC) during which two prominent examples are attested.[15] The first, Lugalannemundu, king of Adab, is claimed by the Sumerian King List (though this is a much later inscription, making the extensive rule of Lugalennemundu somewhat doubtful) to have created a great empire covering the entirety of Mesopotamia, reaching from modern Syria to Iran, saying that he "subjugated the Four Corners".[16] The second, Lugalzaggesi, king of Uruk, conquered the entirety of Lower Mesopotamia and claimed (despite this not being the case) that his domain extended from the upper to the lower sea.[15] Lugalzaggesi was originally titled as simply "King of Uruk" and adopted the title "King of the Land" (Sumerian: lugal-kalam-ma[1]) to lay claim to universal rule.[17] This title had also been employed by some earlier Sumerian kings claiming control over all of Sumer, such as Enshakushanna of Uruk.[1]

Akkadian and Sumerian Kings of the Four Corners (2334–2004 BC)

Sargon, king of Akkad, unified Lower and Upper Mesopotamia, creating the first true Mesopotamian empire. Though Sargon most commonly used the title "King of Akkad" (šar māt Akkadi[18]), he also introduced the more boastful title of šar kiššatim ("King of Everything" or "King of the Universe"), used prominently by his successors.[19] The title of "King of the Four Corners of the World" is first attested to have been used by the Akkadian king Naram-Sin, the grandson of Sargon of Akkad and the fourth ruler of the Akkadian Empire.[2][6] Naram-Sin also proclaimed himself to be a living god (the first Mesopotamian king to do so), making his capital of Akkad not only the political but also the religious center of the empire.[5] It is possible that Naram-Sin might have been inspired to claim the title following his conquest of the city Ebla, in which quadripartite divisions of the world and the universe were prominent parts of the city's ideology and beliefs.[20]

The title of King of the Four Corners suggests that Naram-Sin viewed himself not merely as a Mesopotamian ruler but as a universal ruler who happened to conform to the usual Mesopotamian royal traditions, the monarch of a new empire that not only incorporated the city-states of Mesopotamia but the lands beyond as well. In particular, art made during the period starts to incorporate previously unseen objects such as highland plants and animals and mountains, previously seen as highly foreign objects. Their increasing appearance in art suggests that they were seen as belonging to the empire of Akkad as much as everything else did.[5] It is possible that šar kiššatim referred to the authority to govern the cosmological realm whilst "King of the Four Corners" referred to the authority to govern the terrestrial. Eitherway, the implication of these titles was that the Mesopotamian king was the king of the entire world.[21]

The title doesn't appear to have been used by any of Naram-Sin's direct successors of the Akkadian Empire, which began to collapse during the reign of Naram-Sin's son Shar-Kali-Sharri.[2][6] In the 2100s BC, the Gutians attacked the Akkadian Empire and supplanted the ruling "Sargonic" dynasty, destroying the city of Akkad and establishing an empire of their own.[22] By 2112 BC, the Gutians had been driven out and the city of Ur had become the center of a new Sumerian civilization, referred to as the Third Dynasty of Ur or the Neo-Sumerian Empire. The rulers of this empire emulated the previous monarchs from Akkad, referring to themselves as "Kings of Sumer and Akkad" and all of them—with the exception of the founder of the dynasty, Ur-Nammu—used the title of "King of the Four Corners of the World".[6][23] Some ancient sources confer the title onto Ur-Nammu as well, referring to him as "King in Heaven and the Four Corners of the World", but these inscriptions date to centuries after his reign.[24]

Assyrian Kings of the Four Corners (1366–627 BC)

With the collapse of the Neo-Sumerian Empire in c. 2004 BC, the title fell into disuse once more. Except for the Babylonian king Hammurabi who claimed to be "the king who made the four corners of the Earth obedient" in 1776 BC,[25] the title was not used until occasionally by Assyrian kings of the Middle-Assyrian Empire, often as "King of All the Four Corners of the World" (šar kullat kibrāt erbetti[26]).[27]

The first king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Adad-nirari II (r. 911–891 BC), used the title of "King of the Four Corners".[27] The concept of a king governing the four corners of the world was well-established by the reign of the second king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Tukulti-Ninurta II (r. 891–884 BC), who claimed to have been "he whose honoured name he has pronounced forever for the four corners" (ana mu urut kibrāt erbetti ana dāriš išquru) and "governor of the four corners" (muma'er kibrāt erbetti).[4] In Assyria, the deity Ashur was referred to as "[the one] who makes the king's kingship surpass the kings of the four quarters" (mušarbû šarrūtija eli šarrāni ša kibrāt erbetti).[28]

Tukulti-Ninurta II's son and successor, Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) is in different inscriptions twice referred to as “King of the Totality of the Four Corners including all their rulers” (šar kiššat kibrāte ša napḫar malkī kalîšunu). The title is also attested for his son and successor, Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BC) and is the only title applied to this king by his successors.[4]

The Kition stele, a large basalt stele discovered on Cyprus and the westernmost ancient Assyrian artifact known, identifies the king Sargon II, (r. 722–705 BC) with many titles, including "King of the Universe", "King of Assyria", "King of Sumer and Akkad", "Governor of Babylon" and "King of the Four Corners of the World".[29] Sargon II's son and heir Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) did not immediately inherit the title, referring to himself simply as the "unrivaled king" at the beginning of his reign. Sennacherib conducted several military campaigns during his reign, after which he routinely added titles to his titulary. After his third campaign he added "king of the world" and after conquests in the Mediterranean Sea and Persian Gulf in 694 BC he added the title "King from the Upper Sea of the Setting Sun to the Lower Sea of the Rising Sun". It was only after Sennacherib had conducted campaigns to the south, east, west and north during his fifth campaign that he replaced the title of "unrivaled king" with "King of the Four Corners of the World".[30] Sennacherib's son and heir, Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC) also used the title of "King of the Four Corners of the World" alongside that of "King of the Universe".[3]

Unlike the apparent dynastic inheritance of the title during the Neo-Sumerian Empire, it is possible that the title of King of the Four Corners had to be earned by each Assyrian king individually, thus explaining why the title is not attested for every Neo-Assyrian king and why Sennacherib first used it several years into his reign. British historian Stephanie Dalley, specializing in the Ancient Near East proposed in 1998 that the title may have had to be earned through the king successfully campaigning in all four points of the compass. Dalley also proposed that the similar title of "King of the Universe", with a virtually identical meaning, would have been earned through seven (which would have been connected to totality in the eyes of the Assyrians) successful campaigns.[4] It would thus not have been possible for the king to claim either title before the required military campaigns.[31] Periods during which the title was not used, such as the ~80-year gap between Shalmaneser III and Tiglath-Pileser III, probably reflect periods during which the military activity of the country and its kings declined.[32]

Cyrus the Great (539 BC)

After the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC, the principal power in Mesopotamia was the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nabopolassar, wished to associate himself with the previous Assyrian rulers to establish continuity and assumed many of the same titles such as šarru dannu ("mighty king") and the much older Sumerian "King of Sumer and Akkad" (which had been used by the Neo-Assyrian rulers as well) but do not appear to have assumed the title of King of the Four Corners. Unlike previous ruling dynasties in Mesopotamia, the Neo-Babylonians usually only employed one royal title on any one occasion. Only rarely are examples with more than one royal title in use found from the Neo-Babylonian period, which might explain the absence of "King of the Four Corners..." since this was an additional prestigious title rather than a primary royal title.[18] Nabopolassar's successors abandoned most of the old Assyrian titles, even abandoning the "mighty king" used by Nabopolassar.[33] The only Neo-Babylonian king to assume the title of "King of the Four Corners" was Nabonidus, who in other aspects also tried to emulate the Assyrian kings.[34]

The Neo-Babylonian Empire ended with the conquest of Babylon by the Persian king Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, in 539 BC. The Cyrus Cylinder is an ancient clay cylinder written in Akkadian cuneiform script in the name of Cyrus, made to be used as a foundation deposit and buried in the walls of Babylon.[35] In the text of the cylinder, Cyrus assumes several traditional Mesopotamian titles including those of "King of Babylon", "King of Sumer and Akkad" and "King of the Four Corners of the World".[36][37] The title was not used after the reign of Cyrus but his successors did adopt similar titles. The popular regnal title "King of Kings", used by monarchs of Iran until the modern age, was originally a title introduced by the Assyrian Tukulti-Ninurta I in the 13th century BC (rendered šar šarrāni in Akkadian).[38] The title of "King of Lands", also used by Assyrian monarchs since at least Shalmaneser III,[39] was also adopted by Cyrus the Great and his successors.[40] Titles such as "King of Kings" and "Great-King" (šarru rabu), ancient titles with the connotation of holding supreme power in the lands surrounding Babylon, would remain in use up until the Sassanid dynasty in Persia of the 3rd to 7th centuries.[41][42]

Examples of rulers who used the title

Kings of the Four Corners in the Akkadian Empire:

- Naram-Sin (r. 2254–2218 BC)[5]

Kings of the Four Corners of the Gutian dynasty of Sumer:

- Erridupizir[43]

Kings of the Four Corners in the Neo-Sumerian Empire:

- Utu-hengal[44]

- Shulgi (r. 2094–2047 BC)[6][23]

- Amar-Sin (r. 2046–2038 BC)[6][23]

- Shu-Sin (r. 2037–2029 BC)[6][23]

- Ibbi-Sin (r. 2028–2004 BC)[6][23]

Kings of the Four Corners in Babylonia:

- Hammurabi (r. 1810–1750 BC) – referred to as the "king who made the four corners of the Earth obedient" in 1776 BC.[25]

- Marduk-nadin-ahhe (r. 1099–1082 BC)[45]

- Marduk-shapik-zeri (r. 1082–1069 BC)[45]

Kings of the Four Corners in the Middle Assyrian Empire:

- Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. 1233–1197 BC)[32]

- Tiglath-Pileser I (r. 1114–1076 BC)[27]

- Ashur-bel-kala (r. 1074–1056 BC)[27]

Kings of the Four Corners in the Neo-Assyrian Empire:

- Adad-nirari II (r. 911–891 BC)[27]

- Tukulti-Ninurta II (r. 891–884 BC)[4]

- Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC)[4]

- Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BC)[4]

- Shamshi-Adad V (r. 824–811 BC)[46]

- Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC)[32]

- Shalmaneser V (r. 727–722 BC)[47]

- Sargon II (r. 722–705 BC)[29]

- Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC) – claimed the title from 697 BC.[30]

- Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC)[3]

- Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC)[48]

- Shamash-shum-ukin (Neo-Assyrian king of Babylon, r. 667–648 BC)[49]

- Ashur-etil-ilani (r. 631–627 BC)[49]

Kings of the Four Corners in the Neo-Babylonian Empire:

- Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC)[34]

Kings of the Four Corners in the Achaemenid Empire:

- Cyrus the Great (r. 559–530 BC) – claimed the title from 539 BC.[36][37]

References

Annotations

- ^ There were several titles used by rulers during this period. Lugal is often seen as a title primarily based on a ruler's military prowess, whilst en seems to have implied a more priestly role.[14]

Citations

- ^ a b c Maeda 1981, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Levin 2002, p. 360.

- ^ a b c d Roaf & Zgoll 2001, p. 284.

- ^ a b c d e f g Karlsson 2013, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f Raaflaub & Talbert 2010, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bachvarova 2012, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books Limited. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-14-193825-7.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ The Four Quarters of the World.

- ^ Hallo 1980, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Liverani 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Waltke 2007, p. 456.

- ^ Crawford 2013, p. 283.

- ^ a b Liverani 2013, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Ur III Dynasty.

- ^ McIntosh 2017, p. 167.

- ^ a b Da Riva 2013, p. 72.

- ^ Levin 2002, p. 362.

- ^ Hallo 1980, p. 190.

- ^ Hill, Jones & Morales 2013, p. 333.

- ^ De Mieroop 2004, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Gerstenberger 2001, p. 205.

- ^ Hallo 1966, p. 134.

- ^ a b De Mieroop 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Karlsson 2016, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e Karlsson 2013, p. 255.

- ^ Karlsson 2013, p. 61.

- ^ a b Radner 2010, p. 435.

- ^ a b Russell 1987, p. 530–531.

- ^ Karlsson 2013, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Yamada 2014, p. 43.

- ^ Stevens 2014, p. 73.

- ^ a b Beaulieu 1989, p. 214.

- ^ Cyrus Cylinder.

- ^ a b Cyrus Cylinder Translation.

- ^ a b New Cyrus Cylinder Translation.

- ^ Handy 1994, p. 112.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 258.

- ^ Peat 1989, p. 199.

- ^ Bevan 1902, pp. 241–244.

- ^ Frye 1983, p. 116.

- ^ Selz 2016, p. 74.

- ^ Selz 2016, p. 87.

- ^ a b Brinkman 1968, p. 43.

- ^ Grayson 2002, p. 240.

- ^ Luckenbill 1925, p. 164.

- ^ Karlsson 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Karlsson 2017, p. 11.

Bibliography

- Bachvarova, Mary R. (2012). "From "Kingship in Heaven" to King Lists: Syro-Anatolian Courts and the History of the World". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 12 (1): 97–118. doi:10.1163/156921212X629482.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1989). Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 BC). Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2250wnt. ISBN 9780300043143. JSTOR j.ctt2250wnt. OCLC 20391775.

- Bevan, Edwyn Robert (1902). "Antiochus III and His Title 'Great-King'". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 22: 241–244. doi:10.2307/623929. JSTOR 623929.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1968). Political history of Post-Kassite Babylonia (1158-722 b. C.) (A). Gregorian Biblical BookShop.

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415569675.

- Da Riva, Rocío (2013). The Inscriptions of Nabopolassar, Amel-Marduk and Neriglissar. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-1614515876.

- De Mieroop, Marc Van (2004). A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1405149112.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1983). "The political history of Iran under the Sasanians". The Cambridge History of Iran. 3 (1): 116–180. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521200929.006. ISBN 9781139054942.

- Gerstenberger, Erhard S. (2001). ""World Dominion" in Yahweh Kingship Psalms: Down To the Roots of Globalizing Concepts and Strategies". Horizons in Biblical Theology. 23 (1): 192–210. doi:10.1163/187122001X00107.

- Grayson, A. Kirk (2002) [1996]. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: II (858–745 BC). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0886-0.

- Hallo, William W. (1966). "The Coronation of Ur-Nammu". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 20 (3/4): 133–141. doi:10.2307/1359648. JSTOR 1359648.

- Hallo, William W. (1980). "Royal Titles from the Mesopotamian Periphery". Anatolian Studies. 30: 189–195. doi:10.2307/3642789. JSTOR 3642789.

- Handy, Lowell K. (1994). Among the host of Heaven: the Syro-Palestinian pantheon as bureaucracy. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0931464843.

- Hill, Jane A.; Jones, Philip; Morales, Antonio J. (2013). Experiencing Power, Generating Authority: Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781934536643.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2013). Early Neo-Assyrian State Ideology Relations of Power in the Inscriptions and Iconography of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859) and Shalmaneser III (858–824). Instutionen för lingvistik och filologi, Uppsala Universitet. ISBN 978-91-506-2363-5.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2016). Relations of Power in Early Neo-Assyrian State Ideology. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9781614519683.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2017). Assyrian Royal Titulary in Babylonia (Manuscript). Uppsala University=. S2CID 6128352.

- Levin, Yigal (2002). "Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad". Vetus Testamentum. 52 (3): 350–366. doi:10.1163/156853302760197494.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415679060.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1925). "The First Inscription of Shalmaneser V". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 41 (3): 162–164. doi:10.1086/370064.

- Maeda, Tohru (1981). ""King of Kish" in Pre-Sargonic Sumer". Orient. 17: 1–17. doi:10.5356/orient1960.17.1.

- McIntosh, Jane R. (2017). Mesopotamia and the Rise of Civilization: History, Documents, and Key Questions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1440835469.

- Miller, James Maxwell (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664223588.

- Peat, Jerome (1989). "Cyrus "King of Lands," Cambyses "King of Babylon": The Disputed Co-Regency". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 41 (2): 199–216. doi:10.2307/1359915. JSTOR 1359915.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2010). Geography and Ethnography: Perceptions of the World in Pre-Modern Societies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405191463.

- Radner, Karen (2010). "The stele of Sargon II of Assyria at Kition: A focus for an emerging Cypriot identity?" (PDF). Interkulturalität in der Alten Welt: Vorderasien, Hellas, Ägypten und die vielfältigen Ebenen des Kontakts. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447061711.

- Roaf, Michael; Zgoll, Annette (2001). "Assyrian Astroglyphs: Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone and the Prisms of Esarhaddon". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. 91 (2): 264–295. doi:10.1515/zava.2001.91.2.264. S2CID 161673588.

- Russell, John Malcolm (1987). "Bulls for the Palace and Order in the Empire: The Sculptural Program of Sennacherib's Court VI at Nineveh". The Art Bulletin. 69 (4): 520–539. doi:10.1080/00043079.1987.10788457.

- Selz, Gebhard J. (2016) [1st pub. 2005]. Sumerer und Akkader. Geschichte, Gesellschaft, Kultur [Sumerians and Akkadians. History, society, culture] (in German) (3rd ed.). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-50874-5.

- Stevens, Kahtryn (2014). "The Antiochus Cylinder, Babylonian Scholarship and Seleucid Imperial Ideology" (PDF). The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 134: 66–88. doi:10.1017/S0075426914000068. JSTOR 43286072.

- Waltke, Bruce K. (2007). A commentary on Micah. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4933-5.

- Yamada, Shigeo (2014). "Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III: Chronographic-Literary Styles and the King's Portrait". Orient. 49: 31–50. doi:10.5356/orient.49.31.

Websites

- "British Museum - The Cyrus Cylinder". www.britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Livius - Cyrus Cylinder Translation". www.livius.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Farrokh, Kaveh. "A New Translation of the Cyrus Cylinder by the British Museum". kavehfarrokh.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Epiphany - The Four Quarters of the World". www.binujohn.name. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Yanli, Chen; Yuhong, Wu (2017). "The Names of the Leaders and Diplomats of Marḫaši and Related Men in the Ur III Dynasty". cdli.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.