Hassaniya Arabic

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

| Hassaniya | |

|---|---|

| Mauritanian Arabic | |

| حسانية Ḥassānīya | |

| Native to | Southwestern Algeria, Northwestern Mali, Mauritania, southern Morocco, Northern Niger, Western Sahara |

| Ethnicity | Arabs Arab-Berbers (Sahrawis; Beidane) Haratins Nemadis Imraguen |

| Speakers | 5.2 million (2014–2021)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Arabic alphabet, Latin alphabet (in Senegal) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | mey |

| Glottolog | hass1238 |

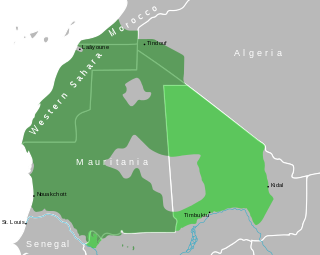

Current distribution of the Hassaniya language. | |

Hassaniya Arabic (Arabic: حسانية, romanized: Ḥassānīya; also known as Hassaniyya, Klem El Bithan, Hassani, Hassaniya, and Maure) is a variety of Maghrebi Arabic spoken by Mauritanian Arabs and the Sahrawi people. It was spoken by the Beni Ḥassān Bedouin tribes of Yemeni origin who extended their authority over most of Mauritania and Morocco's southeastern and Western Sahara between the 15th and 17th centuries. Hassaniya Arabic was the language spoken in the pre-modern region around Chinguetti.

The language has completely replaced the Berber languages that were originally spoken in this region. Although clearly a western dialect, Hassānīya is relatively distant from other Maghrebi variants of Arabic. Its geographical location exposed it to influence from Zenaga-Berber and Wolof. There are several dialects of Hassaniya, which differ primarily phonetically. There are still traces of South Arabian in Hassaniya Arabic spoken between Rio de Oro and Timbuktu, according to G. S. Colin.[4] Today, Hassaniya Arabic is spoken in Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and the Western Sahara.

Phonology

The phonological system of Hassānīya exhibits both very innovative and very conservative features. All phonemes of Classical Arabic are represented in the dialect, but there are also many new phonemes. As in other Bedouin dialects, Classical /q/ corresponds mostly to dialectal /ɡ/; /dˤ/ and /ðˤ/ have merged into /ðˤ/; and the interdentals /θ/ and /ð/ have been preserved. The letter ج /d͡ʒ/ is realised as /ʒ/.

However, there is sometimes a double correspondence of a classical sound and its dialectal counterpart. Thus, classical /q/ is represented by /ɡ/ in /ɡbaðˤ/ 'to take' but by /q/ in /mqass/ 'scissors'. Similarly, /dˤ/ becomes /ðˤ/ in /ðˤəħk/ 'laugh (noun)', but /dˤ/ in /mrˤədˤ/ 'to be sick'. Some consonant roots even have a double appearance: /θaqiːl/ 'heavy (mentally)' vs. /θɡiːl/ 'heavy (materially)'. Some of the "classicizing" forms are easily explained as recent loans from the literary language (such as /qaː.nuːn/ 'law') or from sedentary dialects in case of concepts pertaining to the sedentary way of life (such as /mqass/ 'scissors' above). For others, there is no obvious explanation (like /mrˤədˤ/ 'to be sick'). Etymological /ðˤ/ appears constantly as /ðˤ/, never as /dˤ/.

Nevertheless, the phonemic status of /q/ and /dˤ/ as well as /ɡ/ and /ðˤ/ appears very stable, unlike in many other Arabic varieties. Somewhat similarly, classical /ʔ/ has in most contexts disappeared or turned into /w/ or /j/ (/ahl/ 'family' instead of /ʔahl/, /wak.kad/ 'insist' instead of /ʔak.kad/ and /jaː.məs/ 'yesterday' instead of /ʔams/). In some literary terms, however, it is clearly preserved: /mət.ʔal.lam/ 'suffering (participle)' (classical /mu.ta.ʔal.lim/).

Consonants

Hassānīya has innovated many consonants by the spread of the distinction emphatic/non-emphatic. In addition to the above-mentioned, /rˤ/ and /lˤ/ have a clear phonemic status and /bˤ fˤ ɡˤ mˤ nˤ/ more marginally so. One additional emphatic phoneme /zˤ/ is acquired from the neighbouring Zenaga Berber language along with a whole palatal series /c ɟ ɲ/ from Niger–Congo languages of the south. At least some speakers make the distinction /p/–/b/ through borrowings from French (and Spanish in Western Sahara). All in all, the number of consonant phonemes in Hassānīya is 31, or 43 counting the marginal cases.

| Labial | Interdental | Dental/Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | |||||||

| Nasal | m | mˤ | n | (nˤ) | ɲ | |||||||

| Stop | voiceless | (p) | t | tˤ | c | k | q | (ʔ) | ||||

| voiced | b | bˤ | d | dˤ | ɟ | ɡ | (gˤ) | |||||

| Affricate | (t͡ʃ) | |||||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | χ | ħ | h | |||

| voiced | v | (vˤ) | ð | ðˤ | z | zˤ | ʒ | ʁ | ʕ | |||

| Trill | r | rˤ | ||||||||||

| Approximant | l | lˤ | j | w | ||||||||

On the phonetic level, the classical consonants /f/ and /θ/ are usually realised as voiced [v] (hereafter marked /v/) and [θ̬]. The latter is still, however, pronounced differently from /ð/, the distinction probably being in the amount of air blown out (Cohen 1963: 13–14). In geminated and word-final positions both phonemes are voiceless, for some speakers /θ/ apparently in all positions. The uvular fricative /ʁ/ is likewise realised voiceless in a geminated position, although not fricative but plosive: [qː]. In other positions, etymological /ʁ/ seems to be in free variation with /q/ (etymological /q/, however varies only with /ɡ/).

Vowels

Vowel phonemes come in two series: long and short. The long vowels are the same as in Classical Arabic /aː iː uː/, and the short ones extend this by one: /a i u ə/. The classical diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ may be realised in many different ways, the most usual variants being [eːʲ] and [oːʷ], respectively. Still, realisations like [aj] and [aw] as well as [eː] and [oː] are possible, although less common.

As in most Maghrebi Arabic dialects, etymological short vowels are generally dropped in open syllables (except for the feminine noun ending /-a/ < /-ah/): */tak.tu.biː/ > /tə.ktbi/ 'you (f. sg.) write', */ka.ta.ba/ > */ka.tab/ > /ktəb/ 'he wrote'. In the remaining closed syllables dialectal /a/ generally corresponds to classical /a/, while classical /i/ and /u/ have merged into /ə/. Remarkably, however, morphological /j/ is represented by [i] and /w/ by [u] in a word-initial pre-consonantal position: /u.ɡəft/ 'I stood up' (root w-g-f; cf. /ktəbt/ 'I wrote', root k-t-b), /i.naɡ.ɡaz/ 'he descends' (subject prefix i-; cf. /jə.ktəb/ 'he writes', subject prefix jə-). In some contexts this initial vowel even gets lengthened, which clearly demonstrates its phonological status of a vowel: /uːɡ.vu/ 'they stood up'. In addition, short vowels /a i/ in open syllables are found in Berber loanwords, such as /a.raː.ɡaːʒ/ 'man', /i.vuː.kaːn/ 'calves of 1 to 2 years of age', and /u/ in passive formation: /u.ɡaː.bəl/ 'he was met' (cf. /ɡaː.bəl/ 'he met').

Code-switching

Many educated Hassaniya Arabic speakers also practice code-switching. In Western Sahara it is common for code-switching to occur between Hassaniya Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic, and Spanish, as Spain had previously controlled this region; in the rest of Hassaniya-speaking lands, French is the additional language spoken.

Orthography

Hassaniya Arabic is normally written with an Arabic script. However, in Senegal, the government has adopted the use of the Latin script to write the language, as established by Decree 2005–980 of October 21, 2005.[5]

| Hassaniya Arabic alphabet (Senegal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Ḍ | E | Ë | F | G | H | Ḥ | I | J | K | L | M | N | Ñ | O | Q | R | S | Ṣ | Ŝ | T | Ṭ | Ŧ | U | V | W | X | Ẋ | Y | Z | Ż | Ẓ | ʔ |

| a | b | c | d | ḍ | e | ë | f | g | h | ḥ | i | j | k | l | m | n | ñ | o | q | r | s | ṣ | ŝ | t | ṭ | ŧ | u | v | w | x | ẋ | y | z | ż | ẓ | ʼ |

Speakers distribution

According to Ethnologue, there are approximately three million Hassaniya speakers, distributed as follows:

- Mauritania: 2,770,000 (2006)

- Western Sahara and the southern area of Morocco, known as the Tekna zone: 200,000+ (1995)

- Mali: 175,800 – 210,000 (2000)

- Senegal: 162,000 (2015)

- Algeria: 150,000 (1985)

- Libya: 40,000 (1985)

- Niger: 10,000 (1998)

See also

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2009) |

- ^ Hassaniya at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ "JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE DU MALI SECRETARIAT GENERAL DU GOUVERNEMENT - DECRET N°2023-0401/PT-RM DU 22 JUILLET 2023 PORTANT PROMULGATION DE LA CONSTITUTION" (PDF). sgg-mali.ml. 22 July 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

Article 31 : Les langues nationales sont les langues officielles du Mali.

- ^ "Morocco 2011 Constitution, Article 5". www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved 2021-07-18.

- ^ Norris, H. T. (1962). "Yemenis in the Western Sahara". The Journal of African History. 3 (2): 317–322. ISSN 0021-8537.

- ^ "Decret n° 2005-980 du 21 octobre 2005". Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- Cohen, David; el Chennafi, Mohammed (1963). Le dialecte arabe ḥassānīya de Mauritanie (parler de la Gəbla). Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck. ISBN 2-252-00150-X.

- "Hassaniya, the Arabic of Mauritania", Al-Any, Riyadh S. / In: Linguistics; vol. 52 (1969), pag. 15 / 1969

- "Hassaniya, the Arabic of Mauritania", Al-Any, Riyadh S. / In: Studies in linguistics; vol. 19 (1968), afl. 1 (mrt), pag. 19 / 1968

- "Hassaniya Arabic (Mali) : Poetic and Ethnographic Texts", Heath, Jeffrey; Kaye, Alan S. / In: Journal of Near Eastern studies; vol. 65 (2006), afl. 3, pag. 218 (1) / 2006

- Hassaniya Arabic (Mali) : poetic and ethnographic texts, Heath, Jeffrey / Harrassowitz / 2003

- Hassaniya Arabic (Mali) – English – French dictionary, Heath, Jeffrey / Harrassowitz / 2004

- Taine-Cheikh, Catherine. 2006. Ḥassāniya Arabic. In Kees Versteegh (ed.), Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, 240–250. Leiden: E.~J.~Brill.