History of the Thai Forest Tradition

The Kammatthana meditation tradition originally grew out of the Dhammayut reform movement, founded by Mongkut in the 1820s as an attempt to raise the bar for what was perceived as the "lax" Buddhist practice of the regional Buddhist traditions at the time. Mongkut's reforms were originally focused on scriptural study of the earliest extant Buddhist texts, revival of the dhutanga ascetic practices, and close adherence to the Buddhist Monastic Code (Pali: vinaya). However, the Dhammayut began to have an increasing emphasis on meditation as the 19th century progressed.[1][2] During this time, a newly ordained Mun Bhuridatto went to stay with Ajahn Sao Kantasīlo, who was then the abbot of a small meditation-oriented monastery on the outskirts of Ubon Ratchathani, a province in the predominantly Lao-speaking cultural region of Northeast Thailand known as Isan.

Ajahn Mun learned from Ajahn Sao in the late 19th century, where he studied amidst the growing meditation culture in Isan's Dhammayut monasteries as a result of Mongkut's reforms a half-century earlier. Wandering the rural frontier of Northeast Thailand with Ajahn Sao in rigorous ascetic practices (Pali: dhutanga; Thai: tudong). Ajahn Mun traveled abroad to neighboring regions for a time, hoping to reach levels of meditative adeptness known as the noble attainments (Pali: ariya-phala), which culminate in the experience of Nibbana — the final goal of a Theravada Buddhist practitioner.

After more than two decades of intense meditation and ascetic practice, Ajahn Mun would return to Ubon Ratchathani in 1915, claiming to have found the noble attainments. Word spread in the region, and monks came to study from Ajahn Mun, wishing to put his claims to the test; though the assertions that he had found the noble attainments were not universally received at the time—families were often divided over whether or not Ajahn Mun had attained sainthood.

During this period, Mongkut's successor Chulalongkorn (Rama V of Siam) had consolidated power in Bangkok, and implemented a wave of educational reforms which emphasized the role of the Thai clergy as educators. Dhammayut monks—which included Ajahn Mun and Ajahn Sao and their students—were drafted to teach a new monastic curriculum that had been infused with Western principles in an effort to prevent the encroachment of Christian missionaries, and to prevent Thailand from being colonized by a Western empire.[citation needed] Thailand would successfully prevent colonization; however, Ajahn Mun and Sao's students would continue to evade authorities' attempts to assign them to monasteries and prevent them from practicing in the forest.

Beginning in the 1950s though, the tradition would gain respect among the urbanities in Bangkok, and receive widespread acceptance among the Thai Sangha. Many of the Ajahns were nationally venerated by Thai Buddhists, who regarded them as arahants.[3] Because of their reputations, the Ajahns have become the subject of a cultural fixation on sacralized objects believed among lay followers to offer supernatural protection. This cultural fixation was referred to by social anthropologist Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah as a cult of amulets, which he described during a field study in the 1970s as "a traditional preoccupation now reaching the pitch of fetishistic obsession".[4] During this time, the tradition found a significant following in the West; particularly among the students of Ajahn Chah Subhatto, a forest teacher who studied with a group of monks in the Mahanikai — the other of Thailand's two monastic orders alongside the Dhammayut — many of whom remained loyal to their Mahanikai pedigree in spite of their interest in Ajahn Mun's teachings.[citation needed] However, in the final decades of the 20th century the tradition experienced a crisis when the majority of Thailand's rainforests were clear cut. Because of this, the Forest Tradition in early 21st century Thailand has been characterized by a struggle to preserve the remaining forested lands in Thailand for Buddhist practice.

| Thai Forest Tradition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhikkhus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sīladharās | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Third and Fourth Reigns (1824–1868)

19th Century regional Thai Buddhism

Before authority was centralized in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the region known today as Thailand was a kingdom of semi-autonomous city states (Thai: mueang). These kingdoms were all ruled by a hereditary local governor, and while independent, paid tribute to Bangkok, the more powerful central city state in the region. (see History of Thailand) Each region had its own religious customs according to local tradition, and substantially different forms of Buddhism existed between mueangs.

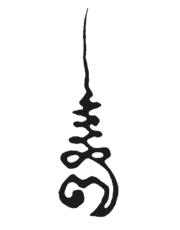

Though all of these local flavors of regional Thai Buddhism evolved their own customary elements relating to local spirit lore, all were shaped by the infusion of Mahayana Buddhism and Indian Tantric traditions, which arrived in the area prior to the fourteenth century.[citation needed] These monks practiced (and some still do to this day)[citation needed] a group of tantric practices known as Khatha Akhom, or Wicha Akhom.[a] Thanissaro writes that these monks would lead sedentary lives in village monasteries; take occupations as doctors and fortune tellers; and occasionally take leave on "a pilgrimage they called 'dhutanga' which bore little resemblance to the classic dhutanga practices."[5] Additionally, these regional traditions differed in the degrees to which they followed the Buddhist monastic code (Pali: Vinaya). Later the regional traditions would be criticized by the central Bangkok ecclesia for not properly adhering to the Vinaya. Tiyavanich writes:

People in villages and towns saw nothing wrong with monks participating in boat races, throwing water at women, or playing chess because they knew the monks and were in fact often their relatives. Many of the monks were sons of villagers who had been ordained at least temporarily, and their lay providers were their parents, aunts and uncles, or acquaintances. But for outsiders — sangha inspectors, Christian missionaries, and Western travelers — the regional monks' behavior was, to say the least, questionable. "In many wats the monks do not behave properly," is a typical remark of a sangha inspector; McCarthy puts it more strongly: "in view of the celibacy of the priesthood the circumstances tend to scandal." Although sangha authorities forbade monks to follow these customs, in remote areas these practices persisted for several decades after the imposition of modern state Buddhism.[citation needed]

Early monkhood of Prince Mongkut

A 20 year old Prince Mongkut took full ordination (ordination name Vajirayan, Pali: Vajirañāṇo) as a Theravada Buddhist monk (Pali: bhikkhu), following a longstanding Thai custom that young men should become monks for a time. The preceptor who conducted Mongkut's ordination was perhaps the most widely known monk in 19th-century Thai history — Mongkut's older half-brother Phra Toh, later known as Somdet Toh.[6][7] The year of Mongkut's ordination, his father (Buddha Loetla Nabhalai – Rama II of Siam) passed away. Although Mongkut was senior to his half-sibling Prince Jessadabodindra (later, Nangklao, Rama III of Siam), the peers in his dynasty instead supported Jessadabodindra to succeed Rama II as the Thai monarch.[8] Giving up aspirations to the throne, Mongkut devoted his life to religion.

In his travels around Siam as a monk, Mongkut quickly became dissatisfied with what he saw as discrepancies between the conduct of the monks and the Vinaya, the Buddhist monastic code.[5] For this reason, Mongkut was concerned about the ability of the ordination lines to be able to trace back to Gautama Buddha, as well as the capacity of the Thai sangha to act as the field by which merit is made among lay people.[9] Mongkut would subsequently seek out a tradition which met his standard of Buddhist practice.

Mongkut eventually found a higher caliber of monastic practice among the Mon people in the region, where he studied Vinaya and traditional ascetic practices or dhutanga.[5] In particular, he met a monk named Buddhawangso, a monk who he admired for his discipline and praxis with respect to the Pāli Canon — the most authoritative Buddhist text in Theravada Buddhism, believed to contain the words of the Buddha and his disciples. Jessadabodindra complained about Mongkut's involvement with the Mons — considering it improper for a member of the royal family to associate with an ethnic minority — and built a monastery on the outskirts of Bangkok. In 1836, Mongkut became the first abbot of Wat Bowonniwet Vihara, which would become the administrative center of the Thammayut order until the present day.[10][11]

The Dhammayut Reform Movement

After reordaining with this group in 1833, he began a reform movement which he named Dhammayut (meaning in accordance with the Dhamma, Thai Dhammayut), a name which he chose to contrast with the regional Buddhist traditions that drew their customs from values which emerged from their respective local cultures.[8] In the founding of the Thammayut, Mongkut made an effort to remove what he understood as non-Buddhist, folk, and superstitious elements which over the years had become part of Thai Buddhism. Additionally, Dhammayut bhikkhus were expected to eat only one meal a day, and the meal was to be gathered during a traditional alms round and eaten together in the monks' single alms bowl; practices above and beyond usual monastic requirements which are usually reserved as optional dhutanga ascetic observances.[12]

In addition to seeking out what Mongkut saw as a more valid ordination lineage, Mongkut sought to find the most reliable version of the Pali Canon still available. Thanissaro asserts that Mongkut did this out of an attempt to make accessible to the Thai sangha successive levels of enlightenment in Theravada Buddhism (known as the noble attainments) which culminate in the experience of Nirvana, after which one becomes an arahant. This motivation was a reaction to an idea which grew out of Sri Lanka, that because of the degeneracy of the human race, the noble attainments were lost to mankind after the first few generations immediately following the Buddha.[13] On his reasons for asking for better versions of the Pali Canon, Mongkut wrote the following in a missive to the Sangha of Sri Lanka:

"Good people should not stay fixed in their original beliefs, but should give their highest respect to the Dhamma-Vinaya, examining it and their beliefs throughout. Wherever their beliefs are right and appropriate, they should follow them. If they can’t practice in line with what is right, they should at least show their appreciation for those who can. If they encounter beliefs and practices that are not right and appropriate, they should judge them as having been remembered wrongly and then discard them".[13]

In the following years Mongkut was visited at Wat Bowonniwet by Western missionaries and sailors, and would learn Latin, English, and astronomy. He would have a close friendship with Vicar Pallegoix of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bangkok, a friendship which would remain after Mongkut became king. Pallegoix visited Wat Bowonniwet regularly to preach Christian sermons. Though Mongkut admired the vicar's presentation of Christian moral ideals, he rejected Christian doctrine, saying: "What you teach people to do is admirable, but what you teach them to believe is foolish."[8]

While abbot of Wat Bowonniwet Mongkut had other monks who were close to him reordain among this Mon lineage. Among these monks was the current Somdet Phra Wannarat "Thap", a grade Nine Pali scholar, and Dhutanga ascetic practicing monk. According to Taylor, Thap was praised as an exemplary Dhammayut monk, and practiced ascetic practices vigorously, as well as contemplations of the foul nature of the body by going to charnel grounds to see decaying corpses in person (a practice which was suggested in the Pali Canon, as an aid to spiritual progress). [14]

Prince Vajirañāṇa, the monk in charge of King Chulalongkorn's fifth-reign educational sangha reforms.

Revival of Dhutanga

During this time charnel grounds were still available for body contemplation. Taylor writes that "The destitute, unable to afford a proper cremation, simply left the dead to the elements and vultures (executed criminals were apparently forbidden a cremation by social custom and were similarly left to the elements), providing a classic environment for “insight” meditation."

Taylor notes that although they were "ascetic monks intent of maintaining correct practices in line with scriptural interpretations", the monks "were not necessarily "forest dwellers"; rather, they were urban-dwelling meditators and Pali scholars . . .", and being away from one's post for too long was frowned upon[15]

Fifth Reign (1868–1910)

Establishment of the Thammayut Order

According to the Dhammayut monk-prince Vajirañāṇa (Thai: Wachirayaan)'s autobiography, dissention in the Dhammayut caused the movement to split into four competing factions (temporarily, albeit for several decades), in part because Thap had irreconcilable differences with some of the more "worldly" monks affiliated with Wat Bowonniwet. In the mid-nineteenth century these branches began to diverge from one another — each developed their own styles for chanting, interpretations and translations of Pali texts, and differed on issues related to the monastic code.[16] During this time, Mongkut passed away, and Prince Vajirañāṇa's elder half-brother Chulalongkorn (Rama V of Siam) succeeded Mongkut to the throne.

Of the four main monasteries that corresponded to the four competing factions were Thap's own Wat Somanat, and Wat Bowonniwet itself, which would have Prince Pawaret — official Dhammayut head in the mid-to-late 19th century, appointed by King Chulalongkorn — as abbot. Prince Pawaret would be unable to reconcile the separate Dhammayut lineages. This separation would continue until Thap and Pawaret both passed away in the early 1890s. Prince Vajirañāṇa succeeded Prince Pawaret in 1893, and took control of a new wave of fifth reign sangha reforms under orders from Chulalongkorn. At this time, Vajirañāṇa was able to reunite the stray Dhammayut lineages that had been so estranged decades earlier.

While Vajirañāṇa was not the official leader of the Sangha (Thai: Sangharaja), the current Sangharaja was a figurehead, and Vajirañāṇa's reforms became the primary focus of the Dhammayut's agenda. Power was consolidated in Bangkok and an emphasis on institutionalized modern education escalated. These scholastic reforms aggressively sought to replace both the regional mysticism practices and Mongkut's sentiment of Buddhist orthodoxy, in favor of a curriculum based on "Victorian notions of reason and utility"[5] which were taught to both King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) and Prince Vajirañāṇa by western tutors (among which was Anna Leonowens — details of which were dramatized in the 1951 musical The King and I). In 1896 King Chulalongkorn wrote a letter to Prince Vajirañana after visiting a secular school founded by the prince:

"Having looked at everything, I am very satisfied and I ask your forgiveness for the disdain I have held in my heart. It’s not that I have felt disdain for the Buddha, for the Dhamma he taught, or for the Sangha of those who have practiced to the point of purity. I’m speaking here of ordinary monks who study the texts and meditation or chant simply for the sake of their own personal happiness. Those who study the texts do so for the sake of their own knowledge, without a thought to teaching others to the best of their ability. This is a way of looking only for their own happiness. Those who meditate are even worse, and those who devote themselves to chanting are the worst of all. This is the disdain that I’ve felt in my heart. But now that I have gazed at what you have accomplished, I see that the elders and their followers in the committee have redeemed themselves from my disdain, and I ask your forgiveness. What you have established is a blessing to the religion, an honor to King Rama IV [Mongkut], and a benefit to the people, from the King on down".[13]

This sentiment would begin to ratify in legislation when the Ecclesiastical Polity Act of 1902 was passed. The Dhammayut movement that King Mongkut began in the fourth-reign was now officially recognized by the Thai government as a Theravada monastic order, and remaining regional traditions not of the Dhammayut lineage were now united as the Maha Nikaya (Thai: Mahanikai). However, Mongkut's fourth-reign Vinaya reforms were to be replaced with a new state recognized code — a compromise between the Pali Vinaya and the traditional Thai disciplines of the regional traditions.[13] Tambiah writes: "The Thammayut brand of Central Thai Buddhism was to be the criterion of pure Buddhism, and regional traditions of Buddhist practice, worship, and identity were to be obliterated in favor of a Bangkok orthodoxy and of Central Thai language as against variant languages . . . ".[17] Concurrent with these administrative groupings were steps to consolidate clerical power in Bangkok. Also, with the 1902 act, an attempt was made through legislation to restrict the freedom of monks to exercise the dhutanga practices and wander the Thai wilderness; ecclesiastical authorities would work to suppress this form of extended countryside wandering with subsequent legislation throughout the 20th century.

Ajahn Mun's Early Years with Ajahn Sao

Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta's first involvement with the Sangha was ordination as a sāmaṇera (novitiate monk) when he was 15 years old. After two years, his father asked him to leave his sāmaṇera status to help out with the family. Having fulfilled his obligations, his parents provided him with his requisites for upasampada and he ordained as a bhikkhu at 22 years old with his parents blessing in 1893.[18] Ajahn Mun left the wat of his preceptor and went to study with the meditation monk Ajahn Sao Kantasīlo at Wat Liap, a small meditation temple just outside Ajahn Mun's hometown.[19]

Little is known of Ajahn Sao Kantasilo, and he left nothing behind in the way of meditation manuals.[20] Taylor writes: "Sao typifies the reclusive somewhat introverted loner. Man [Ajahn Mun] was recorded as saying that Sao's gentle personality was an expression of great metaa [sic]. He would only speak on occasions and with short pithy utternaces."[21] Ajahn Sao began his monastic career in a regional pre-reform tradition practicing khatha meditation, and would later re-ordain in the dhammayut order.

For first three months that Ajahn Mun trained under Ajahn Sao, Ajahn Mun struggled to find a proper meditation subject. Ajahn Mun began by contemplating the foul nature of the body, then received haunting visions of a corpse being picked at by scavengers. Upon investigating these visions, a translucent disk nimitta appeared before him, and when he focused on the translucent disk he would be taken on journey's in his meditation. After three months of following the disk to these visions over and over again, Ajahn Mun decided that there was likely no end to the visions the translucent disk which appeared in his meditation would produce, and concluded that it was a largely unproductive tangent in his meditation practice. He then resolved to keep his awareness in the body at all times.[22]

Countryside wandering with Ajahn Sao

Sao wandered on dhutanga (Thai: thudong) with Mun for several years. Ajahn Mun talked about how during this period, people in the villages were afraid of dhutanga monks who wandered the countryside. Ajahn Maha Bua writes: "Back then, a dhutanga monk, walking in the distance on the far side of a field, was enough to send country folk into a panic. Being fearful, those still close to the village quickly ran home. Those walking near the forest ran into the thick foliage to hide, being too scared to stand their ground or greet the monks. Thus, dhutanga monks, wandering in unfamiliar regions during their travels, seldom had a chance to ask the locals for much needed directions." Tambiah writes:

Such monks apparently provoked feelings of fear and apprehension among the rural folk. Their strictly controlled behaviour and avoidance of unnecessary contact with laymen; their wearing of yellowish-brown robes dyed with gum extracted from the wood of the Jackfruit tree; their carrying a large umbrella (klot) slung over their shoulder, the almsbowl in the other, and a water kettle hanging on the side; and their custom of walking single file — all these features inspired awe as much as respect.[23]

After Ajahns Sao and Mun wandered dhutanga for some years, Ajahn Sao told Ajahn Mun that the latter should go out on his own to progress further. Mun left on his own in search of any teacher who may have found the elusive noble attainments, travelling to Laos, Burma and Central Thailand, and once again he visited his old preceptor Chao Khun Upali for meditation advice. He eventually settled in the mystical Sarika Cave, a subject of many local folk legends, for a period of three years.[5][24]

Sixth Reign (1910–1925)

Ajahn Mun at Sarika Cave

After Ajahn Mun spent the rains with Chao Khun Upali, he headed to Sarika Cave in the Khao Yai mountains, on the border of Central and Northeast Thailand. At first, the local villagers wouldn't take Ajahn Mun to the cave because of a local spirit legend that a terrestrial deva was occupying the cave and killing intruders. This was substantiated by serial accounts of monks who had resided in the cave and subsequently been stricken with fatal illnesses.[25]

Ajahn Mun wasn't dissuaded from staying in Sarika Cave, and saw it as an opportunity for development. On the fourth night staying there, Ajahn Mun developed a severe stomachache, and was unable to digest food and passed blood. Taking a traditional medicine regimen of local herbs for a while, he finally resolved to stop taking them and instead to resort to the "therapeutic power of the Dhamma alone", surrendering fully to his confidence in the Buddhist path to provide a positive outcome, even if he were to die.[26] After a battle with the illness which went on from dusk until midnight, Tambiah writes that Ajahn Mun's mind "realized the nature of the aggregates, and their formations, including the gripping pain, and 'the illness totally disappeared and the mind withdrew into absolute, unshakable one-pointedness'".[26]

When Ajahn Mun's mind emerged to a less absorbed level of concentration, he received a vision where an ethereal demonic giant visited him, black in color and about ten meters high. Tambiah writes: "Ajahn Mun thus was finally confronted with the apparition of the club-wielding demon owner of the cave.[26] In the vision, the demon was made to concede through discourse that its powers didn't match those of the Buddha, the "power of eradicating from his own mind the desire to dominate and harm others".[26] The demon subsequently transformed its appearance into a "gentleman with a mild, courteous manner" and,[27] approaching Ajahn Mun, asked for forgiveness, saying he would reform himself. The spirit revealed himself as chief of a group of terrestrial devas in the region, and offered to serve as Ajahn Mun's guardian for as long as Ajahn Mun stayed.[28]

Ajahn Mun spent the next three years in Sarika Cave. According to Ajahn Maha Bua's spiritual biography of Ajahn Mun, Ajahn Mun received visions where he was visited by a troop of monkeys, and Ajahn Mun understood their grunts and gestures "as clearly as if they had been conversing in human language".[29] In the biography, Ajahn Mun told his students that he finally attained anāgāmi (non-returner) status in 1915 in Sarika Cave.[30][13] The next year, he came back to Isan to instruct his old teacher, Ajahn Sao; and in the years following, he attracted a following of monks desiring a more disciplined approach to Buddhist practice.[5]

Seventh and Eighth Reigns (1925–1946)

Tension between the forest tradition and the Thammayut administrative hierarchy escalated in 1926, when Tisso Uan attempted to drive Ajahn Sing Khantiyagamo, along with his following of 50 monks and 100 nuns and laypeople, out of a forest under Tisso Uan's jurisdiction. Tisso Uan also arranged to have a public notice set up telling villagers not to offer Ajahn Sing and his monks alms. Taylor writes that even after the monks refused to move on a "District Officer came to see Sing, saying that he came on behalf of a provincial directive (from Tisso's office) and again told them to leave. Sing adamantly refused, saying that he was born in Ubon and did not see why he, or his band, had to go as they were causing no problem to anyone." After Ajahns Fun, Orn, and Maha Pin sought advice from Ajahn Mun on the situation (who told them to simply "consider the consequences carefully before acting"), they appealed to the Provincial District Head of Ubon (Chao Khana Changwat). The Provincial District Head "disclaimed any involvement in this dispute. He then gave them a letter to take to the district officer to try to compromise, and the directive was eventually dropped."[31]

This tension would remain for two decades, and Tisso Uan would maintain even after Ajahn Mun's death in 1949 that Ajahn Mun was unqualified as a dhamma teacher without having undergone formal Pali studies.[32][33]

Ninth Reign (1946–)

Mainstream acceptance and the fetishism of amulets

According to Ajahn Lee's autobiography, the relationship between the Thammayut ecclesia and the Kammaṭṭhāna monks changed in the 1950s. When Tisso Uan had become ill, Ajahn Lee went to teach meditation to him to help cope with his illness. Tisso Uan eventually recovered, and a friendship between Tisso Uan and Ajahn Lee began that would cause Tisso Uan to completely reverse his opinion of the Kammaṭṭhāna tradition. Ajahn Lee Dhammadaro writes about what Tisso Uan said to him: "People who study and practice the Dhamma get caught up on nothing more than their own opinions, which is why they never get anywhere. If everyone understood things correctly, there wouldn’t be anything impossible about practicing the Dhamma."

Tisso Uan would then invite Ajahn Lee to teach in the city. This event marked a turning point in relations between the Dhammayut administration and the Forest Tradition. Thanissaro notes that widespread acceptance from the Dhammayut ecclesia would come in part because the clergy who had been drafted as teachers from the Fifth Reign onwards were now being displaced by civilian teaching staff.[13][34]

Mainstream popularity culminated in the 1970s, when a cultural fetishism of medallions worn as neckpieces became popular. Busts of popular forest ajahns have been featured, and they are often ritually blessed to provide some supramundane charm to the wearer. Tambiah writes that General Kriangsak Chanaman distributed amulets to his troops, and ordered that white cloths with mystical yantra designs which were blessed by Luang Pu Waen be bound to the Thai National Flag and flown at the top of ship's masts for protection from communist vessels.

Cold war tensions

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2016) |

Tensions arose between the dictatorial Thai government and a newly formed communist party in Thailand. Several of the major figures in the Kammaṭṭhāna tradition alive at the time were accused of communist sympathies.[35]

The Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah

Ajahn Chah Subhaddo was a Mahanikai monk who practiced in Ajahn Mun's tradition. Ajahn Chah primarily practiced under the instruction of Ajahn Kinnaree, although he met Ajahn Mun once, and studied under Ajahn Thongrat (although no record exists of the extent that they spent time together).[36] According to Ajahn Jayasaro, Ajahn Chah didn't like to spend a lot of time with teachers, and when he did he didn't ask a lot of questions, but instead liked to observe and learn from their behavior. Ajahn Jayasaro writes that "Despite the profound impression Luang Boo Mun made upon him for instance, he stayed with that great master a mere two days and never returned for a second visit. Teachers were a resource that he drew upon to inform his own singular aspiration and self-discipline."

Before studying under Ajahn Kinaree extensively, Ajahn Chah wandered dhutanga from 1946–1954, accompanied by his friend Pra Tawan.[37] Ajahn Jayasaro notes that they wandered in "the traditional manner of the wandering mendicant or tudong monk, carrying their iron bowls in a cloth bag on one shoulder and their glots on the other." They usually walked single file for fifteen miles a day, and the end of the day find a stream to bathe in, set up their glot umbrella tents under trees nearby, and practice meditation at night.[38]

In 1967, Ajahn Chah founded Wat Pah Pong. That same year, an American monk from another monastery, Venerable Sumedho (later Ajahn Sumedho) came to stay with Ajahn Chah at Wat Pah Pong. He found out about the monastery from one of Ajahn Chah's existing monks who happened to speak "a little bit of english".[39] In 1975, Ajahns Chah and Sumedho founded Wat Pah Nanachat, an international forest monastery in Ubon Ratchatani which offers services in English. In the 1980s the Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah expanded to the West with the founding of Chithurst Buddhist Monastery and Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in the UK, and has since expanded to cover Canada, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, and the United States.[40]

Deforestation

In the last half of the 20th century, the vast majority of Thailand's rainforest were lost. Millions of villagers in the forest were (sometimes violently) driven from their homes as villages were bulldozed over to make room for eucalyptus plantations. Tiyavanich writes:

The final closure of the forest began after devastating floods occurred in southern Thailand. In November 1988 floods and landslides, triggered by rain falling on denuded hillsides, wiped out several southern villages and killed hundreds of people. For the first time the Bangkok government was forced to face the consequences of uncontrolled exploitation of the forest. Responding to an intense public outcry, the government suspended and later banned all logging activities in the country. It is no surprise that such ecological disasters have struck Thailand. Three decades of rapacious land clearing had wiped out 82 percent of Thailand’s forests, and in places the countryside had become a dust bowl. In this context, many wandering monks decided that they had to hold their ground when they found a suitable forest. They knew that if they retreated, they risked losing it forever.[41]

In the 1990s, Members of the Forestry Bureau deeded tracts of land to forest monasteries in an effort to preserve wilderness. These monasteries along with the land surrounding them, have turned into sort of "forested islands".[13][42]

According to Thanissaro, with the accreditation of their education system to administer graduate programs, Dhammayut authorities in Bangkok began to feel that its ties with the Forest tradition were no longer necessary, and the Dhammayut hierarchy would align itself with the economic interests of the Mahanikai hierarchy.

Activism

During 1997 Asian financial crisis, Ajahn Maha Bua began a program to underwrite the Thai Currency with gold bars donated by Thai citizens, raising some 12 tonnes of gold bars and 10 million in currency in order to save the country.[43] The government under Chuan Leekpai tried to thwart Ajahn Maha Bua's efforts, and the political fallout from Ajahn Maha Bua's successful campaign would influence the 2001 general election in Thailand, when Ajahn Maha Bua endorsed Thaksin Shinawatra.[13]

Ajahn Maha Bua would appear to have reversed his support in 2005, when portions of a sermon from Ajahn Maha Bua were published in Manager Daily, a thai newspaper, accusing Prime Minister Thaksin of aiming for a Thai Presidency calling his administration a "savage and atrocious power". According to Taylor, Ajahn Maha Bua was incited by an anti-Thaksin group that runs Manager Daily, who presented his words out of context to attack Thaksin's political party in order to posture themselves for a coup d'état in 2006.[44]

References

- ^ Team, Mindworks (2018-07-07). "Where Does Meditation Come From? Meditation History & Origins". Mindworks. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

- ^ Psychologist, Joaquín Selva, Bc S. (2017-03-13). "The History and Origins of Mindfulness". PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor 1993, p. 15.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f Thanissaro 2010.

- ^ Thanissaro 2006, 2.

- ^ McDaniel 2011.

- ^ a b c Bruce 1969.

- ^ http://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/download/2304034/2304040 [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 696.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 156.

- ^ "Forest Monks: Origins of the Thai Forest Tradition of Buddhist Monks".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thanissaro 2005.

- ^ Taylor 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Taylor 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Taylor 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 162.

- ^ http://www.buddhanet.net/pdf_file/acariya-mun.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 82.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 83.

- ^ Taylor 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Maha Bua Nyanasampanno 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 84.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 86.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c d Tambiah 1984, p. 87.

- ^ Maha Bua Nyanasampanno 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Maha Bua Nyanasampanno 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Tambiah 1984, p. 88.

- ^ Taylor 2008, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Thanissaro 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Taylor 2008, p. 138.

- ^ Taylor 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Tiyavanich 1997, p. 229.

- ^ https://tisarana.ca/static/books/jayasaro_the_biography_of_luang_por_chah_%28draft_2007%29.pdf

- ^ https://tisarana.ca/static/books/jayasaro_the_biography_of_luang_por_chah_%28draft_2007%29.pd

- ^ https://tisarana.ca/static/books/jayasaro_the_biography_of_luang_por_chah_%28draft_2007%29.pdf page 41

- ^ ajahnchah.org [full citation needed]

- ^ Harvey 2013, p. 443.

- ^ Tiyavanich 1997, p. 245.

- ^ Schuler 2014, p. 64.

- ^ http://asiafoundation.org/in-asia/2011/08/10/u-s-economic-crisis-recalls-shared-sacrifice-and-compromise-in-thailand%E2%80%99s-past/

- ^ Taylor 2008, p. 120.

Sources

- Secondary sources

- Bruce, Robert (1969). "King Mongkut of Siam and his Treaty with Britain". Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 9. Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch: 88–100. JSTOR 23881479.

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- "Rattanakosin Period (1782 -present)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- Gundzik, Jephraim (2004). "Thaksin's populist economics buoy Thailand". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 2004-08-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521859424.

- Lopez, Alan Robert (2016). Buddhist Revivalist Movements: Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement. Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Maha Bua Nyanasampanno, Ajahn (2010), Patipada: Venerable Acariya Mun's Path of Practice, Wisdom Library

- McDaniel, Justin Thomas (2011), The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand, Columbia University Press

- Orloff, Rich (2004), "Being a Monk: A Conversation with Thanissaro Bhikkhu", Oberlin Alumni Magazine, 99 (4)

- Pali Text Society, The (2015), The Pali Text Society's Pali-English Dictionary

- Piker, Steven (1975), Piker, Steven (ed.), "Modernizing Implications of 19th Century Reforms in the Thai Sangha", Contributions to Asian Studies, Volume 8: The Psychological Study of Theravada Societies, E.J. Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004658363, ISBN 9004043063

- Quli, Natalie (2008), "Multiple Buddhist Modernisms: Jhana in Convert Theravada" (PDF), Pacific World 10:225–249

- Robinson, Richard H.; Johnson, Willard L.; Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (2005). Buddhist Religions: A Historical Introduction. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-55858-1.

- Schuler, Barbara (2014). Environmental and Climate Change in South and Southeast Asia: How are Local Cultures Coping?. Brill. ISBN 9789004273221.

- Scott, Jamie (2012), The Religions of Canadians, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 9781442605169

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1984). The Buddhist Saints of the Forest and the Cult of Amulets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27787-7.

- Taylor, J. L. (1993). Forest Monks and the Nation-state: An Anthropological and Historical Study in Northeastern Thailand. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3016-49-1.

- Taylor, Jim [J.L.] (2008), Buddhism and Postmodern Imaginings in Thailand: The Religiosity of Urban Space, Ashgate, ISBN 9780754662471

- Thanissaro (2005), Jhana Not by the Numbers, Access to Insight

- Thanissaro (2006), Legends of Somdet Toh, Access to Insight

- Thanissaro (2010), The Customs of the Noble Ones, Access To Insight

- Tiyavanich, Kamala (January 1997). Forest Recollections: Wandering Monks in Twentieth-Century Thailand. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1781-7.

- Zuidema, Jason (2015), Understanding the Consecrated Life in Canada: Critical Essays on Contemporary Trends, Wilfrid Laurier University Press