History of Zürich

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2009) |

Zürich has been continuously inhabited since Roman times. The vicus of Turicum was established in AD 90, at the site of an existing Gaulish (Helvetic) settlement.

Gallo-Roman culture appears to have persisted beyond the collapse of the Western empire in the 5th century, and it is not until the Carolingian period. A royal castle was built at the site of the Lindenhof, and monasteries are established at Grossmünster and Fraumünster.

Political power lay with these abbeys during Medieval times, until the guild revolt in the 14th century which led to the joining of the Swiss Confederacy. Zürich was the focus of the Swiss Reformation led by Huldrych Zwingli, and it came to riches with silk industry in Early Modern times.

Early history

Numerous lake-side settlements from the Neolithic and Bronze Age have been found, such as those in the Zürich Pressehaus and Zürich Mozartstrasse. The settlements were found in the 1800s, submerged in Lake Zürich. Located on the then swamp land between the Limmat and Lake Zürich around Sechseläutzenplatz on small islands and peninsulas in Zürich, Prehistoric pile dwellings around Lake Zürich were set on piles to protect against occasional flooding by the Linth and Jona. Zürich–Enge Alpenquai is located on Lake Zürich lakeshore in Enge, a locality of the municipality of Zürich. It was neighbored by the settlements at Kleiner Hafner and Grosser Hafner on a then peninsula respectively island in the effluence of the Limmat, within an area of about 0.2 square kilometres (49.42 acres) in the city of Zürich. As well as being part of the 56 Swiss sites of the UNESCO Worl Heritage Site Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, the settlement is also listed in the Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance as a Class object.[1][2][3]

In 2004, traces of a previously unknown pre-Roman Celtic (La Tène culture) settlement were discovered, the center of which lay on the Lindenhof hill respectively the area around the Münsterhof square besides the Limmat. The Celtic Helvetians had a settlement when they were succeeded by the Romans, who established a custom station here for goods going to and coming from Italy. At the later Vicus Turicum, probably in the first 1st century BC or even much earlier, the Celts settled at the Lindenhof Oppidium. In 1890, so-called Potin lumps were found, whose largest weights 59.2 kilograms (131 lb) at the Prehistoric pile dwelling settlement Alpenquai. The pieces consist of a large number of fused Celtic coins, which are mixed with charcoal remnants. Some of the 18,000 coins originate from the Eastern Gaul, others are of the Zürich type, that were assigned to the local Helvetii, which date to around 100 BC.[4][5] There's also an island sanctuary of the Helvetii in connection with the settlement at the preceding Oppidi Uetliberg on the former Grosser Hafner island.[6] at the Sechseläutenplatz on the effluence of the Limmat on Lake Zürich lake shore.

A female who died in about 200 BC found buried in a carved tree trunk during a construction project at the Kern school complex in March 2017 in Aussersihl. Archaeologists revealed that she was approximately 40 years old when she died and likely carried out little physical labor when she was alive. A sheepskin coat, a belt chain, a fancy wool dress, a scarf and a pendant made of glass and amber beads were also discovered with the woman.[7][8][9][10][11]

The Roman Vicus Turicum first belonged to the province of Gallia Belgica, and to Germania superior from AD 90. Following Constantine's reform of the Empire in 318, the border between the praetorian prefectures of Gaul and Italy was just east of Turicum crossing the Linth between Lake Zürich and Walensee. Roman Turicum was not fortified, but there was a small garrison at the tax-collecting point, set up not exactly on the border, but downstream of Lake Zürich, where the goods entering Gaul were loaded onto larger ships. South of the castle, at the location of the St. Peter church, there was a temple to Jupiter. The earliest record of the town's name is preserved on a 2nd-century tombstone found in the 18th century on Lindenhof, referring to the Roman castle as "STA(tio) TUR(i)CEN(sis)".

The area was Christianised along with the rest of the Roman Empire, during the 4th century. According to legend, saints Felix and Regula were executed at the location of the Wasserkirche in 286.[12]

The Alamanni settled in the Swiss plateau from the 5th century, but the Roman castle persisted into the 7th century. The earliest manuscript mention of the settlement, as castellum turegum, describes the mission of Columban in 610. An 8th-century list of toponyms from Ravenna mentions Ziurichi. There is a legendary account of an Alamannic duke Uotila residing on, and giving his name to, the Uetliberg.

Holy Roman Empire

Zürich was part of Frankish-ruled Alemannia from 746, following the blood court at Cannstatt, lying in the Turgowe (Thurgau) dominated by Konstanz.

A Carolingian castle, built on the site of the now ruined Roman castle by the grandson of Charlemagne, Louis the German, is mentioned in 835 ("in castro Turicino iuxta fluvium Lindemaci"). Louis also founded the Fraumünster abbey on 21 July 853 for his daughter Hildegard. He endowed the Benedictine convent with the lands of Zürich, Uri, and the Albis forest, and granted the convent immunity, placing it under his direct authority.

In the wake of this, during the 9th century, Zürich gradually acquired the characteristics of a medieval city. It was now the center of the separate county of Zürichgau, detached from the older county of Thurgau. The early city was dominated by the Fraumünster convent. In 1045, King Henry III granted the convent the right to hold markets, collect tolls, and mint coins, and thus effectively made the abbess the ruler of the city.

The Frankish kings had special rights over their tenants, were the protectors of the two churches, and had jurisdiction over the free community. In 870 the sovereign placed his powers over all four in the hands of a single official (the Reichsvogt), and the union was still further strengthened by the wall built round the four settlements in the 10th century as a safeguard against Saracen marauders and feudal barons.

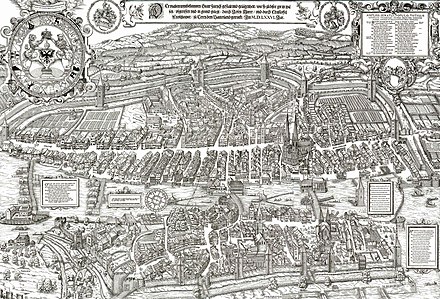

Zürich became reichsunmittelbar (direct control of the emperor) in 1218 with the extinction of the main line of the Zähringer family. A city wall was built during the 1230s, enclosing 38 hectares (about 94 acres). The Bahnhofstrasse marks the course of the western moat, Hirschengraben marks the eastern moat. The earliest citizens' stone houses at the Rennweg date to this period, using the dilapidated Carolingian castle as a quarry. Emperor Frederick II promoted the abbess of the Fraumünster to the rank of a duchess in 1234. The abbess assigned the mayor, and she frequently delegated the minting of coins to citizens of the city.

The Reichsvogtei passed to the counts of Lenzburg (1063–1173), and then to the dukes of Zahringen (extinct 1218). Meanwhile, the abbess of the Benedictine Frau Münster had been acquiring extensive rights and privileges over all the inhabitants, though she never obtained the criminal jurisdiction. The town flourished greatly in the 12th and 13th centuries, the silk trade being introduced from Italy.

In 1218 the Reichsvogtei passed back into the hands of the king, who appointed one of the burghers as his deputy, the town thus becoming a free imperial city under the nominal rule of a distant sovereign. The abbess in 1234 became a princess of the empire, but power rapidly passed from her to the council which she had originally named to look after police, but which came to be elected by the burghers, though the abbess was still the lady of Zürich. This council (all powerful since 1304) was made up of the representatives of certain knightly and rich mercantile families (the patricians), who excluded the craftsmen from all share in the government, though it was to these last that the town was largely indebted for its rising wealth and importance.

Predigerkirche was built in 1231 AD as a Romanesque church of the then Dominican Predigerkloster nearby the Neumarkt and the city's hospital.[13] As the other convents in Zürich, it was abolished after the Reformation in Switzerland.[14]

In October 1291 the town made an alliance with Uri and Schwyz, and in 1292 failed in a desperate attempt to seize the Habsburg town of Winterthur. After that Zürich began to display strong Austrian leanings, which characterize much of its later history. In 1315 the men of Zürich fought against the Swiss Confederates at the Battle of Morgarten.

The Codex Manesse, a major source of medieval German poetry, was written and illustrated in the early 14th century in Zürich. Among the collection are poems by Süsskind von Trimberg. Very little is known about Süsskind, but scholars speculate that he was a Jew, as the name “Süsskind” was only given to Jews at the time.[15] The first official mention of Jews in Zürich was in 1273. The existence of a synagogue in the 13th century testifies to an active Jewish community.[16] When the Black Death epidemic came to Switzerland in 1348/49, the Jews were widely accused of having poisoned wells. On the 24th of February 1349, the city's Jews were tortured, burned and driven out of Zürich.

From 1354, Jews began to re-settle in Zürich, but from 1400, the legal situation of Jews in Zürich began to deteriorate. A 1404 law forbade them from testifying against Christians in court, and in 1423 they were indefinitely expelled from the city.[17]

In the later medieval period, the political power of the convent slowly waned. The beginning of self-government came with the establishment of the Zunftordnung (guild laws) in 1336 by Rudolf Brun, who also became the first independent mayor, i.e. not assigned by the abbess. From this time, the city increasingly came under the domination of the Zünfte, a process only fully completed in the 16th century with the suspension of the monasteries following the Reformation. Jews were excluded from the guilds, which were based on the concept of Christian brotherhood.

Under the new constitution (the main features of which lasted till 1798) the Little Council was made up of the burgomaster and thirteen members from the Constafel (which included the old patricians and the wealthiest burghers) and the thirteen masters of the craft guilds, each of the twenty-six holding office for six months.

The Great Council of 200 (really 212) members consisted of the Little Council, plus 78 representatives each of the Constafel and of the guilds, besides 3 members named by the burgomaster. The office of burgomaster was created and given to Brun for life. Out of this change arose a quarrel with one of the branches of the Habsburg family, in consequence of which Brun was induced to throw in the lot of Zürich with the Swiss Confederation (May 1351).

The double position of Zürich as a free imperial city and as a member of the Everlasting League was soon found to be embarrassing to both parties. In 1373 and again in 1393 the powers of the Constafel were limited and the majority in the executive secured to the craftsmen, who could then aspire to the burgomastership. Meanwhile, the town had been extending its rule far beyond its walls, a process which began in the 14th, and attained its height in the 15th century (1362–1467).

Old Swiss Confederacy

Zürich joined the Swiss confederation (which at that point was a loose confederation of de facto independent states) as the fifth member in 1351. Zürich was expelled from the confederation in 1440 due to a war with the other member states over the territory of Toggenburg (the Old Zürich War). Zürich was defeated in 1446, and re-admitted to the confederation in 1450.

During the later half of the 15th century, Zürich managed to substantially increase the territory under its control, gaining the Thurgau (1460), Winterthur (1467), Stein am Rhein (1459/84) and Eglisau (1496). Zürich's position in the Confederacy was improved further with its role in the Burgundy Wars under Hans Waldmann. From 1468 to 1519, Zürich was the Vorort of the Federal Diet.

This thirst for territorial aggrandizement brought about the first civil war in the Confederation (the "Old Zürich War," 1436-50), in which, at the Battle of St. Jakob an der Sihl (1443), under the walls of Zürich, the men of Zürich were completely beaten and their burgomaster Stissi slain. The purchase of the town of Winterthur from the Habsburgs (1467) marks the culmination of the territorial power of the city.

It was to the men of Zürich and their leader Hans Waldmann that the victory of Morat (1476) was due in the Burgundian War; and Zürich took a leading part in the Italian campaign of 1512–15, the burgomaster Schmid naming the new duke of Milan (1512). No doubt her trade connections with Italy led her to pursue a southern policy, traces of which are seen as early as 1331 in an attack on the Valle Leventina and in 1478, when Zürich men were in the van at the fight of Giornico, won by a handful of Confederates over 12,000 Milanese troops.

In 1400 the town obtained from the King Wenceslaus the Reichsvogtei, which carried with it complete immunity from the empire and the right of criminal jurisdiction. As early as 1393 the chief power had practically fallen into the hands of the Great Council, and in 1498 this change was formally recognized. (Derived from Free Public Domain: Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition)

This transfer of all power to the guilds had been one of the aims of the burgomaster Hans Waldmann (1483–89), who wished to make Zürich a great commercial centre. He also introduced many financial and moral reforms, and subordinated the interests of the country districts to those of the town. He practically ruled the Swiss Confederation, and under him Zürich became the real capital of the League. But such great changes excited opposition, and he was overthrown and executed. His main ideas were embodied, however, in the constitution of 1498, by which the patricians became the first of the guilds, and which remained in force till 1798; some special rights were also given to the subjects in country districts. It was the prominent part taken by Zürich in adopting and propagating (against the strenuous opposition of the Constafel) the principles of the Reformation (the Fraumünster Abbey being suppressed in 1524) which finally secured for it the lead in the Confederation. The Augustiner and Prediger monasteries and Oetenbach nunnery and Rüti Monastery nearby Rapperswil were also disestablished in 1524. The aftermath of the Reformation in Zürich resulted also in the abolishment of the Zürich convent, the worship in the churches were discontinued, and the buildings and income of the monasteries were assigned to an according Amt, a bailiwick of administratively function of the city's government (Rat).

Reformation

Zwingli started the Swiss reformation at the time when he was the main preacher in Zürich at the Grossmünster. He started his preaching there by preaching systematically through Matthew which was a huge difference from almost every other priest that preached through the liturgical cycle of readings issued by the Church.

He lived and preached in Zürich from 1484 until his death in 1531 at the defeat of Zürich in the second war of Kappel. Zwingli's Zürich Bible first appeared in 1531 and continued to be revised until the present day. Katharina von Zimmern (1478-1547), the last abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey, supported the peaceful introduction of the reformation in Zürich.[18][19]

Early Modern history

An important source for Zürich under Heinrich Bullinger is the Wickiana, a collection of curious documents from 1560 to 1587. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the patriciate and council of Zürich adopted an increasingly aristocratic and isolationist attitude. A sign of this was the second ring of impressive city ramparts was built in 1642 under the impression of the Thirty Years' War.

The funds required for this ambitious project were imposed on the subject territories without consultation, resulting in revolts that were crushed by force. From 1648, the city changed its official status from Reichsstadt to Republik, thus likening itself to city republics like Venice and Genova.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a distinct tendency becomes observable in the town government to limit power to the actual holders. Thus the country districts were consulted for the last time in 1620 and 1640; and a similar breach of the charters of 1489 and 1531 (by which the consent of these districts was required for the conclusion of important alliances, war and peace, and might be asked for as to other matters) occasioned disturbances in 1777.

The council of 200 came to be largely chosen by a small committee of the members of the guilds actually sitting in the council by the constitution of 1713 it consisted of 50 members of the Little Council (named for a fixed term by the Great Council), 18 members named by the Constafel, and 144 selected by the 12 guilds, these 162 (forming the majority) being co-opted for life by those members of the two councils who belonged to the gild to which the deceased member himself had belonged.

Early in the 18th century a determined effort was made to crush by means of heavy duties the flourishing rival silk trade in Winterthur. It was reckoned that about 1650 the number of privileged burghers was 9000, while their rule extended over 170,000 persons. The first symptoms of active discontent appeared later among the dwellers by the lake, who founded in 1794 a club at Stäfa and claimed the restoration of the liberties of 1489 and 1531, a movement which was put down by force of arms in 1795. The old system of government perished in Zürich, as elsewhere in Switzerland, with the French invasion in the spring of 1798, and under the Helvetic constitution the country districts obtained political liberty.[20]

Modern history

Napoleonic era

Zürich lost much of its power in the Helvetic Republic, with territory lost to the Aargau, the Thurgau and the Canton of Linth. In 1799, the city became even a battlefield of the French Revolutionary Wars of the Second Coalition, at the First Battle of Zürich in June and the Second Battle of Zürich in September. Gottfried Keller became an intellectual influence on the Radical "free-thinking" side in the formation of Switzerland as a federal state.

The environs of Zürich are famous in military history on account of the two battles of 1799 (French Revolutionary Wars). In the first battle (4 June) the French under General André Masséna, on the defensive, were attacked by the Austrians under the Archduke Charles, Massena retiring behind the Limmat before the engagement had reached a decisive stage. The second and far more important battle took place on 25 and 26 September. Massena, having forced the passage of the Limmat, attacked and totally defeated the Russians and their Austrian allies under Korsakov's command.

19th century

In 1839, the city had to yield to the demands of its rural subjects, following the Züriputsch of 6 September. Most of the ramparts built in the 17th centuries were torn down, without ever having been sieged, to allay rural concerns over the city's hegemony. The Limmatquai was built in several stages between 1823 and 1859 along the right side of the Limmat. From 1847, the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn, the first railway on Swiss territory, connected Zürich with Baden, putting the Zürich Hauptbahnhof at the origin of the Swiss rail network. The present building of the Hauptbahnhof dates to 1871. The emergence of the Sechseläuten as the city's (more properly, the Zünfte's) most prominent traditional holiday dates to this period.

The Ötenbach monastery, founded 1285, fell victim to the increasingly grand city planning in 1902, with the entire Lindenhof hill it was built on removed to make way for the new Uraniastrasse and administration buildings. It had been serving as a prison, and the inmates were moved to the newly completed cantonal prison in Regensdorf. But under the cantonal constitution of 1814 matters were worse still, for the town (10,000 inhabitants) had 130 representatives in the Great Council, while the country districts (200,000 inhabitants) had only 82. A great meeting at Uster on 22 November 1830 demanded that two-thirds of the members in the Great Council should be chosen by the country districts. In 1831 a new constitution was drawn up on these lines, the town getting 71 representatives as against 141 allotted to the country districts, though it was not till 1837-38 that the town finally lost the last relics of the privileges which it had so long enjoyed as compared with the country districts.

From 1803 to 1814 Zürich was one of the six directorial cantons, its chief magistrate becoming for a year the chief magistrate of the Confederation, while in 1815 it was one of the three cantons, the government of which acted for two years as the Federal government when the diet was not sitting. In 1833 Zürich tried hard to secure a revision of the Federal constitution and a strong central government.

The town was the Federal capital for 1839–40, and consequently the victory of the Conservative party there in 1839 (due to indignation at the nomination by the Radical government to a theological chair in the university of David Strauss, the author of the famous Life of Jesus) caused a great stir throughout Switzerland. But when in 1845 the Radicals regained power at Zürich, which was again the Federal capital for 1845–46, that town took the lead in opposing the Sonderbund cantons.

It of course voted in favor of the Federal constitutions of 1848 and of 1874, while the cantonal constitution of 1869 was remarkably advanced for the time. The enormous immigration from the country districts into the town from the "thirties" onwards created an industrial class which, though "settled" in the town, did not possess the privileges of burghership, and consequently had no share in the municipal government.

First of all in 1860 the town schools, opened to "settlers" only on paying high fees, were made accessible to all, next in 1875 ten years' residence ipso facto conferred the right of burghership.

In 1862, Jews were given full legal and political equality, and that same year, the Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zürich was founded. Jews had begun to re-settle in Zürich over the course of the 19th century, following 400 years of exclusion.[21]

The Quaianlagen and Quaibrücke are important milestones in the development of the modern city of Zürich, as by the construction of the new lake front, Zürich was transformed from the medieval small town on the Limmat and Sihl to an attractive modern city on the Lake Zürich lake shore, unter the guidance of the city engineer Arnold Bürkli.

The town and canton continued to be on the Liberal, or Radical, or even Socialistic side, while from 1848 to 1907 they claimed 7 of the 37 members of the Federal executive or Bundesrat, these 7 having filled the presidential chair of the Confederation in twelve years, no canton surpassing this record. From 1833 onwards the walls and fortifications of Zürich were little by little pulled down, thus affording scope for the extension and beautification of the town. In 1915 the tenant organization Mieterverband was founded in Zürich.

Merger of municipalities

In 1893, the city was extended (grosse Eingemeindung) to include the (former) villages of Wollishofen, Enge, Leimbach, Wiedikon, Wipkingen, Fluntern and Hottingen, and the then-recently built-up areas of Aussersihl (formerly part of Wiedikon, a municipality since 1787), Oberstrass, Unterstrass, Riesbach and Hirslanden.

In 1934, the city borders were again extended, to the inclusion of the former villages, by that time de facto suburbs, of Albisrieden, Altstetten, Höngg, Affoltern, Seebach, Oerlikon, Schwamendingen and Witikon (kleine Eingemeindung).

There were no changes between 1934 and 2013, but as of December 2014[update] occurred in all two further mergers (Eingemeindungen) of municipalities in the canton of Zürich. As per 1 January 2014 Bertschikon bei Attikon and Wiesendangen merged to Wiesendangen,[22][23] and on 1 January 2015 Bauma and Sternenberg merged to Bauma.[24][25] Therefore, the Canton of Zürich comprises now of 169 municipalities.

1940s to present

Zürich was accidentally bombed during World War II. With many Jews seeking refuge in Switzerland, funds were raised, not by Swiss authorities, but by the SIG (Israelite Community of Switzerland). The central committee for refugee aid, created in 1933, was located in Zürich.

An economic boom set in after World War II, lasting into the 1960s.

The further, for that time extremely high subventions, but lacking of alternative governmental cultural programs for the youth in Zürich, occurred in 1980 to the so-called Opernhauskrawalle youth protests – Züri brännt,[26] meaning Zürich is burning, documented in the Swiss documentary film Züri brännt (movie). The most prominent politician involved was Emilie Lieberherr, then member of the city's executive (Stadtrat) authorities. In 1982, communal elections resulted in the first conservative majority in 53 years (president Thomas Wagner 1982–1990), but in the early 1980s, Emilie Lieberherr and Ursula Koch where the first female politicians in Zürich's exekutive authority Stadtrat,[27] both representing the social-democratic SP political party.[28]

From 1990, there has again been a leftist majority (presidents Josef Estermann 1990, Elmar Ledergerber 2002, Corine Mauch 2009, all of the Social Democratic Party). The introduction of liberal laws (Gastgewerbegesetz 1997) favoured the development of Zürich's role as regional center of nightlife; also during the 1990s, a liberalisation of zoning laws (Bau- und Zonenordnung 1992; Stadtforum 1996) led to a renewal of construction activity (Technopark 1991–93, Steinfels-Areal 1993, Zürich West 1998), Growing suburbanization since the 1960s had resulted in congestions due to commuting, partly eased with the Zürich S-Bahn, introduced 1990. Population declined during the 1980s to 1990s, but began to increase again in the 2000s, paired with significant gentrification of central areas.

Demographic history

Zürich during its period of territorial expansion and prosperity during the late 14th to early 15th century increased in population to an estimated 7,000 inhabitants. This figure decreased rapidly as a result of the Old Zürich War, to some 5,000, comparable to the population of Berne, Schaffhausen or Lucerne.

Population grew slowly but steadily during the 16th to 18th centuries, reaching 10,000 by 1800. Population then increased rapidly during the 19th century, due to industrialization, and the increased availability of building space after the destruction of the city walls in the 1830s, reaching 28,000 by 1888.[29]

Counting the population within the modern city borders, the figures are 17'200 in 1800, 56,700 in 1871, 150,700 in 1900, and 251,000 in 1930. Population grew rapidly during 1945–1965, peaking at 440,000. After 1965, population declined due to suburbanization, to below 360,000 in the 1990s. After 2000, there has again been population growth, surpassing the 400,000 mark in 2014.[30]

See also

- History of the Jews in Zürich

- Fortifications of Zürich

- Reformation in Zürich

- Staatsarchiv Zürich

- Timeline of Zürich

- History of Switzerland

References

- ^ "A-Objekte KGS-Inventar". Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Amt für Bevölkerungsschutz. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Prehistoric Pile Dwellings in Switzerland". Swiss Coordination Group UNESCO Palafittes (palafittes.org). Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "World Heritage". palafittes.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Keltisches Geld in Zürich: Der spektakuläre «Potinklumpen». Amt für Städtebau der Stadt Zürich, Stadtarchäologie, Zürich October 2007.

- ^ Michael Nick. "75 kilogrammes of Celtic small coin - Recent research on the "Potinklumpen" from Zürich" (PDF). Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, España. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Beat Eberschweiler: Schädelreste, Kopeken und Radar: Vielfältige Aufgaben für die Zürcher Tauchequipe IV. In: NAU 8/2001. Amt für Städtebau der Stadt Zürich, Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Unterwasserarchäologie / Labor für Dendrochronologie. Zürich 2001.

- ^ July 2019, Laura Geggel-Associate Editor 30 (30 July 2019). "Iron Age Celtic Woman Wearing Fancy Clothes Buried in This 'Tree Coffin' in Switzerland". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Solly, Meilan. "This Iron Age Celtic Woman Was Buried in a Hollowed-Out Tree Trunk". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Kelte trifft Keltin: Ergebnisse zu einem aussergewöhnlichen Grabfund - Stadt Zürich". www.stadt-zuerich.ch (in German). Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Margaritoff, Marco (6 August 2019). "Iron Age Celtic Woman Found Buried In A Hollowed-Out Tree Trunk In Zurich". All That's Interesting. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Iron Age Celtic Woman Buried in 'Tree Trunk Coffin' Discovered in Switzerland". Geek.com. 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dölf Wild, Urs Jäggin, Felix Wyss: Predigerkirche Zürich (31 December 2006). "Die Zürcher Predigerkirche – Wichtige Etappen der Baugeschichte. Auf dem Murerplan beschönigt? – Untersuchungen an der Westfassade der Predigerkirche" (in German). Amt für Städtebau der Stadt Zürich. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Kleine Zürcher Verfassungsgeschichte 1218–2000" (PDF) (in German). Staatsarchiv Zürich. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Röthe, Gustav (1894). Süsskind von Trimberg. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 37. Leipzig. pp. 334–336.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wild, Dölf und Matt, Christoph Philipp. Zeugnisse jüdischen Lebens aus den mittelalterlichen Städten Zürich und Basel, in: Kunst und Architektur in der Schweiz. Synagogen. pp. 14–20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Antisemitismus". Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Geschichte" (in German). Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ "Frauenehrungen" (in German). Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ derived from Free Public Domain: Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- ^ ""Judentum", in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz HLS online, 2016". Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Bertschikon and Wiesendangen merged to Wiesendangen on 1 January 2014.

- ^ "Bertschikon" (in German). Zürcher Oberländer. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Bauma and Sternenberg merged to Bauma on 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Dossier Sternenberg" (in German). Zürcher Oberländer. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "10vor10 - TV - SRF Player" (in German). 10vor10. 16 January 2015. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Wo ist Ursula Koch?" (in German). Schweiz aktuell. 6 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Bernard Degen (24 January 2013). "Sozialdemokratische Partei (SP)" (in German). HDS. Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Verzeichnis der Bürger der Stadt Zürich Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine (1889).

- ^ 1962: 440,180 (maximum); 1980: 370,618; 1989: 355,901 (minimum); 1990: 356,352; 1995: 360,826; 2000: 360,980; 2005: 366,809; 2010: 385,468; January 2014: 400,028 (31.7% foreigners) stadt-zuerich.ch

Bibliography

47°22′N 8°33′E / 47.367°N 8.550°E / 47.367; 8.550