History of Rajasthan

The history of human settlement in the western Indian state of Rajasthan dates back to about 100,000 years ago. Around 5000 to 2000 BCE many regions of Rajasthan belonged as the site of the Indus Valley Civilization. Kalibangan is the main Indus site of Rajasthan, here fire altars have been discovered, similar to those found at Lothal.[1]

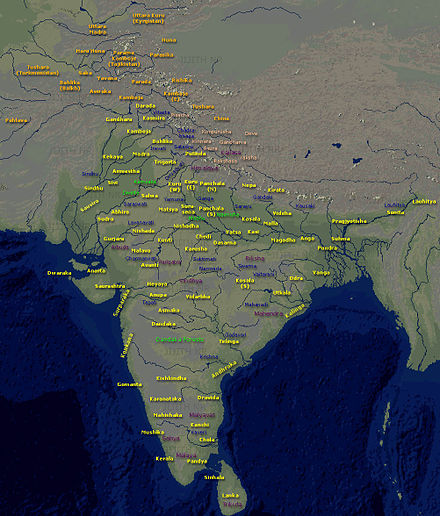

Around 2000 BCE, Sarasvati River flowed through the Aravalli mountain range in the state. During the Vedic Period present Rajasthan region known as Brahmavarta (The land created by the gods and lying between the divine rivers Saraswati and Drishadwati). Matsya Kingdom (c. 1500–350 BCE) was the one of the most important Vedic kingdom. The main ruler of kingdom was king Virata, who participated in Kurukshetra War by the side of Pandavas. After Vedic Period, Rajasthan was ruled by many Mahajanapadas includes- Matsya, Surasena, Kuru, Arjunayanas, Sivis and others.

The early medieval period saw the rise of many Rajput kingdoms such as the Chauhans of Ajmer, Sisodias of Mewar, Gurjara-Pratihara and the Rathores of Marwar, as well as several Rajput clans such as the Gohil and the Shekhawats of Shekhawati.[2] The Gurjara-Pratihara Empire acted as a barrier for Arab invaders from the 8th to the 11th century, it was the power of the Pratihara army that effectively barred the progress of the Arabs beyond the confines of Sindh, their only conquest for nearly 300 years.[3]

Prithviraj Chauhan led a coalition who defeated the Ghurid army; the Gohils and Sisodia of Chittor, who continued to resist the Mughals against heavy odds eventually gave rise to the leadership of Maharana Hammir, Maharana Kumbha, Maharana Sanga, Maharana Pratap and Maharana Raj Singh.[4]

In his long military career, Maharana Sanga achieved a series of unbroken successes against several neighbouring Muslim kingdoms, most notably the Lodi dynasty of Delhi. He united several Rajput clans for the first time since the Second Battle of Tarain and marched against the Timurid ruler Babur.[5] Maharana Pratap in the 16th century, both men became a symbol of Rajput valour against the Mughal invasions.[6]

The other famous rulers of Rajasthan includes Maldeo Rathore of Marwar, Rai Singh of Bikaner and Kachhawa rulers of Jaipur include Man Singh I and Sawai Jai Singh. While Jat kingdoms rise in early modern period include the Johiya of Jangaldesh, the Sinsinwars of Bharatpur State, as well as the Bamraulia clan and the Ranas of Dholpur. Maharaja Suraj Mal was the greatest Jat ruler of Rajasthan.[7] Maharaja Ganga Singh of Bikaner State was the notable ruler of modern period. His greatest achievement was the completion of Gang Canal Project in 1927.[8]

Among many of Rajasthan's most important architectural works are the Jantar Mantar, Dilwara Temples, Lake Palace Resort, City Palace of Jaipur, City Palace of Udaipur, Chittorgarh Fort, Jaisalmer Havelis and Kumbhalgarh also known as the Great Wall of India.

The British made several treaties with rulers of Rajasthan and also made allies out of local rulers, who were allowed to rule their princely states. This period was marked by famines and economic exploitation. The Rajputana Agency was a political office of the British Indian Empire dealing with a collection of native states in Rajputana (present, Rajasthan).[9]

After Indian Independence in 1947, the various princely states of Rajputana were integrated in seven stages to formed present day state of Rajasthan on 1 November 1956.

Periodization of Rajasthan history

- Pre-historic Period (Stone Age)

- Early Stone Age (c. 10,00,000 – 1,00,000 BCE)

- Middle Stone Age (c. 1,00,000 – 40,000 BCE)

- Later Stone Age (c. 40,000 – 8000 BCE)

- Neolithic Age (c. 8000 – 5000 BCE)

- Proto-historic Period (c. 5000 – 1500 BCE)

- Chalcolithic Age (c. 5000 – 3000 BCE)

- Bronze Age (c. 3000 – 1500 BCE)

- Iron-Age and Ancient Period (c. 1500 – 300 BCE)

- Vedic Period (c. 1500 – 600 BCE)

- Mahajanapadas and Tribal kingdoms (c. 600 BCE – 300 BCE)

- In this period Rajasthan was ruled by Kingdoms like Sivi, Salwa, Malava and others. These kingdoms also ruled under Maurya Empire.

- Classical Period (c. 300 BCE – 550 CE)

- Many tribal kingdoms ruled independently under Kushan Empire, Gupta Empire.

- Early Medieval Period (c. 550 – 1000 CE)

- This period is also known as "Rajput Period", because of rise of many Rajput dynasties and kingdoms.

- Late Medieval Period (c. 1000 – 1568 CE)

- This period marked by struggles and resistance against Muslim expansion by Rajput kingdoms.

- Modern Period (c. 1568–1947 CE)

- Mughal invasions and resistance against them. (c. 1568–1720)

- Maratha influences (c. 1720–1817)

- Princely states of Rajputana ruled under British Empire (c. 1817 – 1947)

- Post-independence Period (c. 1947 onwards)

- Unification of Rajasthan (c. 1948 – 1956)

Proto-historic Period (c. 5000–1500 BCE)

Indus Valley civilisation

Sindhu–Saraswati civilization, or the Indus Valley civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of India, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE.

- Baror (Sri Ganganagar) and Karanpura (Hanumangarh) are major Indus-Valley Civilization sites of Rajasthan.

Kalibangān civilization

Kalibangān is a town located in Tehsil Pilibangān in Hanumangarh district. It is also identified as being established in the triangle of land at the confluence of Drishadvati and Sarasvati River. The prehistoric and Pre-Mauryan character of Indus Valley civilization was first identified by Luigi Tessitori at this site. Kalibangan's excavation report was published in its entirety in 2003 by the Archaeological Survey of India, 34 years after the completion of excavations.

The report concluded that Kalibangan was a major provincial capital of the Indus Valley Civilization. Kalibangan is distinguished by its unique "fire altars" and world's earliest attested "ploughed field".It is around 2900 BCE that the region of Kalibangan developed into what can be considered a planned city.

The Kalibangan pre-historic site was discovered by Luigi Pio Tessitori, an Italian Indologist (1887–1919). He was doing some research in ancient Indian texts and was surprised by the character of ruins in that area. He sought help from John Marshall of the Archaeological Survey of India.

The excavation unexpectedly brought to light a twofold sequence of cultures, of which the upper one (Kalibangan I) belongs to the Harappan, showing the characteristic grid layout of a metropolis and the lower one (Kalibangan II) was formerly called pre-Harappan but is now called "Early Harappan or antecedent Harappan". Other nearby sites belonging to IVC include Balu, Kunal, Banawali etc.[10][11]

Ganeshwar civilization

Ganeshwar is located near the copper mines of the Sikar-Jhunjhunu area of the Khetri copper belt in Rajasthan. The Ganeshwar-Jodhpura culture has over 80 other sites currently identified.[12]

The period was estimated to be 3000–2000 BCE. Historian Ratna Chandra Agrawala wrote that Ganeshwar was excavated in 1977. Excavations revealed copper objects including arrowheads, spearheads, fish hooks, bangles and chisels. With its microliths and other stone tools, Ganeshwar culture can be ascribed to the pre-Harappan period.

Ganeshwar saw three cultural phases:

- Period 1 (3800 BCE) which was characterized by hunting and gathering communities using chert tools

- Period II (2800 BCE) shows the beginnings of metal work in copper and fired clay pottery

- Period III (1800 BCE) featured a variety of pottery and copper goods being produced.[13]

Ancient and Classical Period (c. 1500 BCE – 550 CE)

Matsya Kingdom (c. 1400–350 BCE)

Matsya Kingdom was one of the solasa (sixteen) Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms). Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) chiefdoms in the region were succeeded by Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) from c. 700–500 BCE, associated with the rise of the great mahajanapada states (mahajanapada states Kuru, Panchala, Matsya, Surasena and Vatsa)[14]

It was located in central India near Kuru. It was founded by Matsya Dwaita, a son of the great emperor Uparachira Vasu.[15]

Geography

To the north of Central Matsya was Kuru. Kuru territories like Yakrilloma were located to the east. To its west was Salwa, and to its northwest was Mahothha. Nishada, Nishadha, and Kuru territories like Navarashtra were located in south of Matsya.[16]

History and in Kurukshetra War

The entire Matsya royal family came to fight for the Pandavas in the Mahabharata war. Virata came with his brothers, Uttara, and Shankha. Shweta also came from the south with his son Nirbhita.

On the first day, Uttara died fighting Shalya. At the death of his half-brother, Shweta was infuriated and started wreaking havoc in the Kuru armies. Bhishma came and killed him. On the seventh day, Dronacharya killed Shankha and Nirbhita. On the fifteenth day, Dronacharya killed Virata. All of Virata's brothers also died fighting Dronacharya. The remnant of the Matsya army was slaughtered at midnight by Ashwastamma on the eighteenth day.[17]

By the late Vedic period, they ruled a kingdom located south of the Kurus, and west of the Yamuna river which separated it from the kingdom of the Panchalas. It roughly corresponded to Jaipur in Rajasthan, and included the whole of Hindaun, Alwar with portions of Bharatpur as well as South Haryana. The capital of Matsya was at Viratanagari (present-day Bairat) which is said to have been named after its founder king, Virata.[18]

Matsya Union

In the modern era, another United States of Matsya was a brief union of four princely states of Bharatpur, Dholpur, Alwar and Karauli temporarily put together from 1947 to 1949.[19] Shobha Ram Kumawat of Indian National Congress was the first and last chief minister of the State from 18 March 1948 until 15 May 1949.[19] Maharaja of Dholpur became its Rajpramukh.

On 15 May 1949, the Matsya Union was merged with Greater Rajasthan,[20] to form the United State of Rajasthan, which later became the state of Rajasthan on 26 January 1950.[15]

Ancient kingdoms (c. 700 BCE–550 CE)

Northern Rajasthan area

Eastern Rajasthan area

Central Rajasthan area

Western Rajasthan area

Southern Rajasthan area

These warrior kingdoms defeated many foreign invaders like Saka, Huna, and others.

Foreign empires invasion (c. 100–300CE)

These foreign kingdoms ruled some parts of western & northeast parts of Rajasthan, they also face strong opposition from indigenous kingdoms like Sivi, Arjunayanas, Yaudheya and Malava.

Later these foreign kingdoms were defeated by the Satavahanas and the Guptas.

Early Medieval Period (c. 550–1000 CE)

Gurjara-Pratihara Empire (c. 550–1036 CE)

The Gurjar Pratihar Empire acted as a barrier for Arab invaders from the 6th to the 11th century. The chief accomplishment of the Pratihars lies in its successful resistance to foreign invasions from the west, starting in the days of Junaid. During the Umayyad campaigns in India (740), an alliance of rulers under Nagabhata I defeated the Arabs in 711 CE, and forced them to retreat to Sindh.[21] Historian R. C. Majumdar says that this was openly acknowledged by the Arab writers. He further notes that historians of India have wondered at the slow progress of Muslim invaders in India, as compared with their rapid advance in other parts of the world. There seems little doubt that it was the power of the Pratihara army that effectively barred the progress of the Arabs beyond the confines of Sindh, their only conquest for nearly 300 years.[22]

Pratiharas of Mandavyapura (c. 550–860 CE)

The Pratiharas of Mandavyapura Pratīhāras of Māṇḍavyapura), also known as the Pratiharas of Mandore (or Mandor), were an Indian dynasty. They ruled parts of the present-day Rajasthan between 6th and 9th centuries CE. They first established their capital at Mandavyapura (modern Mandore), and later ruled from Medantaka (modern Merta).

The imperial Pratiharas also claimed descent from the legendary hero Lakshmana. The earliest known historical members of the family are Harichandra and his second wife Bhadra. Harichandra was a Brahmin, while Bhadra came from a Kshatriya noble family. They had four sons: Bhogabhatta, Kakka, Rajjila and Dadda. These four men captured Mandavyapura and erected a rampart there.[23] It is not known where the family lived before the conquest of Mandavyapura.[24]

Pratiharas of Bhinmala (Kannauj) (c. 730–1036)

Nagabhata I (730–760), was originally perhaps a feudatory of the Chavdas of Bhillamala. He gained prominence after the downfall of the Chavda kingdom in the course of resisting the invading forces led by the Arabs who controlled Sindh. Nagabhata Pratihara I (730–756) later extended his control east and south from Mandor, conquering Malwa as far as Gwalior and the port of Bharuch in Gujarat. He established his capital at Avanti in Malwa, and checked the expansion of the Arabs, who had established themselves in Sind. In Battle of Rajasthan (738 CE), Nagabhata led a confederacy of Pratiharas to defeat the Muslim Arabs who had until then been pressing on victorious through West Asia and Iran.

The Arab chronicler Sulaiman describes the army of the Pratiharas as it stood in 851 CE, "The ruler of Gurjara maintains numerous forces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry. He is unfriendly to the Arabs, still he acknowledges that the king of the Arabs is the greatest of rulers. Among the princes of India there is no greater foe of the Islamic faith than he. He has got riches, and his camels and horses are numerous."[25]

Mihira Bhoja was the Greatest ruler of dynasty, kingdoms which were conquered and acknowledged his Suzerainty includes Travani, Valla, Mada, Arya, Gujaratra, Lata Parvarta and Chandelas of Bundelkhand. Bhoja's Daulatpura-Dausa Inscription(AD 843), confirms his rule in Dausa region. Another inscription states that, "Bhoja's territories extended to the east of the Sutlej river."

Mahmud of Ghazni captured Kannauj in 1018, and the Pratihara ruler Rajapala fled. He was subsequently captured and killed by the Chandela ruler Vidyadhara.[26][27] The Chandela ruler then placed Rajapala's son Trilochanpala on the throne as a proxy. Jasapala, the last Gurjara-Pratihara ruler of Kannauj, died in 1036.

Pratihara Art

There are notable examples of architecture from the Gurjara-Pratihara era, including sculptures and carved panels.[28] Their temples, constructed in an open pavilion style. One of the most notable Gurjara-Pratihara style of architecture was Khajuraho, built by their vassals, the Chandelas of Bundelkhand

- Māru-Gurjara architecture

Māru-Gurjara architecture was developed during Gurjara Pratihara Empire.

- Mahavira Jain temple, Osian

Mahavira Jain temple, Osian temple was constructed in 783 CE,[29] making it the oldest surviving Jain temple in western India.

- Baroli temples complex

Baroli temples complex are eight temples, built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas, is situated within a walled enclosured.[30]

Other Pratihara branches

- Baddoch branch (c. 600–700)

Known Baddoch rulers are:

- Dhaddha 1 (600–627)

- Dhaddha 2 (627–655)

- Jaibhatta (655–700)

- Rajogarh branch

Badegujar were rulers of Rajogarh

- Parmeshver Manthandev, (885–915)

- No records found after Parmeshver Manthandev

Kingdom of Mewar (c. 566–1948 CE)

Guhila dynasty (c. 566–1303 CE)

The Guhila dynasty ruled the Medapata (modern Mewar) region in present-day Rajasthan state of India. In the 6th century, three different Guhila dynasties are known to have ruled in present-day Rajasthan:

- Guhilas of Nagda-Ahar,

- Guhilas of Kishkindha (modern Kalyanpur),

- Guhilas of Dhavagarta (present-day Dhor).

None of these dynasties claimed any prestigious origin in their 7th century records.[31] The Guhilas of Dhavagarta explicitly mentioned the Mori (later Maurya) kings as their overlords, and the early kings of the other two dynasties also bore the titles indicating their subordinate status.[32][page needed] By the 10th century, the Guhilas of Nagda-Ahar were the only among the three dynasties to have survived. By this time, their political status had increased, and the Guhila kings had assumed high royal titles such as Maharajadhiraja.

During this period, the dynasty started claiming a prestigious origin, stating that its founder Guhadatta was a mahideva (Brahmin) who had migrated from Anandapura (present-day Vadnagar in Gujarat).[33] R. C. Majumdar theorizes that Bappa achieved a highly significant military success, because of which he gained reputation as the dynasty's founder.[34]

The later bardic chronicles mention a fabricated genealogy, claiming that the dynasty's founder Guhaditya was a son of Shiladitya, the Maitraka ruler of Vallabhi. This claim is not supported by historical evidence.[35] According to the 977 CE Atpur inscription and the 1083 CE Kadmal inscription, Guhadatta was succeeded by Bhoja, who commissioned the construction of a tank at Eklingji. The 1285 Achaleshwar inscription describes him as a devotee of Vishnu.[36] Bhoja was succeeded by Mahendra and Nagaditya. The bardic legends state that Nagaditya was killed in a battle with the Bhils.[36]

Nagaditya's successor Shiladitya raised the political status of the family significantly, as suggested by his 646 CE Samoli inscription, as well as the inscriptions of his successors, including the 1274 Chittor inscription and the 1285 Abu inscription. R. V. Somani theorizes that the copper and zinc mines at Jawar were excavated during his reign, which greatly increased the economic prosperity of the kingdom. Mahendra was succeeded by Kalabhoja, who has been identified as Bappa Rawal by several historians including G. H. Ojha.[37]

In the mid-12th century, the dynasty divided into two branches. The senior branch (whose rulers are called Rawal in the later medieval literature) ruled from Chitrakuta (modern Chittorgarh), and ended with Ratnasimha's defeat against the Delhi Sultanate at the 1303 Siege of Chittorgarh. The junior branch ruled from Sesoda with the title Rana, and gave rise to the Sisodia Rajput dynasty.

Branching of Guhil dynasty

Ranasingh (1158), during his reign, the Guhil dynasty got divided into two branches.[38] The Post-split Rawal branch ruled from 1165–1303 CE.

Sisodia dynasty (c. 1326–1948 CE)

The Sisodia dynasty traced its ancestry to Rahapa, a son of the 12th century Guhila king Ranasimha. The main branch of the Guhila dynasty ended with their defeat against the Khalji dynasty at the Siege of Chittorgarh (1303). In 1326, Rana Hammir who belonged to a cadet branch of that clan; however reclaimed control of the region, re-established the dynasty, and also became the propounder of the Sisodia dynasty clan, a branch of the Guhila dynasty, to which every succeeding Maharana of Mewar belonged, the Sisodias regain control of the former Guhila capital Chittor.[39][40][41]

The most notable Sisodia rulers were Rana Hamir (r. 1326–1364), Rana Kumbha (r. 1433–1468), Rana Sanga (r. 1508–1528) and Rana Pratap (r. 1572–1597). The Bhonsle clan, to which the Maratha empire's founder Shivaji belonged, also claimed descent from a branch of the royal Sisodia family.[42] Similarly, Rana dynasty of Nepal also claimed descent from Ranas of Mewar.[43]

Bhati dynasty of Jaisalmer (c. 600–1949 CE)

Bhati comes from Bhatner and take control of this region. The Maharajas of Jaisalmer trace their lineage back to Jaitsimha, a ruler of a Bhati clan, through Deoraj, a famous prince of the Yaduvanshi Bhati, a Rajput ruler during the 9th century. With him the title of "Rawal" commenced. "Rawal" means "of the Royal house".[44]

Foundation of Kingdom

According to legend, Deoraj was to marry the daughter of a neighbouring chief. Deoraj's father and 800 of his family and followers were surprised and massacred at the wedding. Deoraj escaped with the aid of a Brahmin yogi who disguised the prince as a fellow Brahmin. When confronted by the rival chief's followers hunting for Deoraj, the Brahmin convinced them that the man with him was another Brahmin by eating from the same dish, something no Brahmin holy man would do with someone of another caste. Deoraj and his remaining clan members were able to recover from the loss of so many such that later he built the stronghold of Derawar.[45] Deoraj later captured Laudrava (located about 15 km to the south-east of Jaisalmer) from another Rajput clan and made it his capital.[45]

The major opponents of the Bhati were the Rathor clans of Jodhpur and Bikaner. They used to fight battles for the possession of forts and waterholes as from early times the Jaisalmer region had been criss-crossed by camel caravan trade routes which connected northern India and central Asia with the ports of Gujarat on the Arabian Sea coast of India and hence on to Persia and Arabia and Egypt. Jaisalmer's location made it ideally located as a staging post and for imposing taxes on this trade.[46]

The Bhati rulers originally ruled parts of Afghanistan; their ancestor Rawal Gaj is believed to have founded the city of Gajni. According to James Tod, this city is present-day Ghazni in Afghanistan, while Cunningham identifies it as modern-day Rawalpindi. His descendant Rawal Salivahan is believed to have founded the city of Sialkot and made it his new capital. Salivahan defeated the Saka Scythians in 78 CE at Kahror, assuming the title of Saka-ari (foe of the Sakas). Salivahan's grandson Rawal Bhati conquered several neighbouring regions. It is from him that the Bhati clan derives its name.[47]

Derawar fort

Derawar fort was first built in the 9th century CE by Rai Jajja Bhati, a Hindu Rajput ruler of the Bhati clan,[48] as a tribute to Rawal Deoraj Bhati the king of Jaisalmer and Bahawalpur.[49][50] The fort was initially known as Dera Rawal, and later referred to as Dera Rawar, which with the passage of time came to be pronounced Derawar, its present name.[50]

Medieval Period

In 1156, Rawal Jaisal established his new capital in the form of a mud fort and named it Jaisalmer after himself.

The first Jauhar of Jaisalmer occurred in 1294, during the reign of Turkic ruler of Delhi, Alauddin Khalji. It was provoked by Bhatis' raid on a massive treasure caravan being transported on 3000 horses and mules.[51]

Princely state of Jaisalmer

In 1818, the Rawals of Jaisalmer State signed a treaty with the British, and was guaranteed the royal succession. Jaisalmer was one of the last rajput states to sign a treaty with the British. Jaisalmer was forced to invoke the provisions of the treaty and call on the services of the British in 1829 to avert a war with Bikaner and 10 years later in 1839 for the First Anglo-Afghan War.[52]

Chauhan dynasty (c. 650–1315 CE)

Chauhan dynasty or Chahamana dynasty was a great power from 6th 12th century, Chauchan dynasty ruled more than 400 years. Chauchan was a Rajput dynasty that ruled modern parts of Rajasthan, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh and Delhi. They sacrificed all they have & also self for protecting of Motherland from Maleechas. Chahamanas were classifies the dynasty among the four Agnivanshi Rajput clans, whose ancestors are said to have come out of Agnikund sacrificial fire pit. The earliest sources to mention this legend are the 16th century recensions of Prithviraj Raso.

- The ruling dynasties belonging to the Chauhan clan included:

- Chahamanas of Shakambhari (Chauhans of Ajmer)

- Chahamanas of Naddula (Chauhans of Nadol)

- Chahamanas of Jalor (Chauhans of Jalore); branched off from the Chahamanas of Naddula

- Chahamanas of Ranastambhapura (Chauhans of Ranthambore); branched off from the Chahamanas of Shakambhari

- Chahamanas of Lata

- Chahamanas of Dholpur

- Chahamanas of Partabgarh

- The princely states ruled by families claiming Chauhan descent include:[53]

Chahamanas of Shakambhari (c. 650–1194 CE)

The Chahamanas of Shakambhari (IAST: Cāhamāna), colloquially known as the Chauhans of Sambhar, were a dynasty that ruled parts of the present-day Rajasthan and its neighbouring areas in India, between 6th and 12th centuries. The territory ruled by them was known as Sapadalaksha. They were the most prominent ruling family of the Chahamana (Chauhan) clan, and were categorized among Agnivanshi Rajputs in the later medieval legends.

The Chahamanas originally had their capital at Shakambhari (present-day Sambhar Lake Town). Until the 10th century, they ruled as Pratihara vassals. When the Pratihara power declined after the Tripartite Struggle, the Chahamana ruler Simharaja assumed the title Maharajadhiraja. In the early 12th century, Ajayaraja II moved the kingdom's capital to Ajayameru (modern Ajmer). For this reason, the Chahamana rulers are also known as the Chauhans of Ajmer.

Territory

As the Chahamana territory expanded, the entire region ruled by them came to be known as Sapadalaksha. or Jangladesh.[54] This included the later Chahamana capitals Ajayameru (Ajmer) and Shakambhari (Sambhar).[55] The term also came to be applied to the larger area captured by the Chahamanas. The early medieval Indian inscriptions and the writings of the contemporary Muslim historians suggest that the following cities were also included in Sapadalaksha:- Hansi (now in Haryana), Mandore (now in Marwar region), and Mandalgarh (now in Mewar region).[56]

History

The earliest historical Chahamana king is the 6th century ruler Vasudeva.

The Ana Sagar lake in Ajmer was commissioned by the Chahamana ruler Arnoraja. The subsequent Chahamana kings faced several Ghaznavid raids. Ajayaraja II (r. c. 1110–1135) repulsed a Ghaznavid attack, and also defeated the Paramara king Naravarman. He moved the kingdom's capital from Shakambhari to Ajayameru (Ajmer), a city that he either established or greatly expanded.[57] His successor Arnoraja raided the Tomara territory, and also repulsed a Ghaznavid invasion. However, he suffered setbacks against the Gujarat Chaulukya kings Jayasimha Siddharaja and Kumarapala, and was killed by his own son Jagaddeva.[58]

Arnoraja's younger son Vigraharaja IV greatly expanded the Chahamana territories, and captured Delhi from the Tomaras. The most celebrated ruler of the dynasty was Someshvara's son Prithviraja III, better known as Prithviraj Chauhan. He defeated several neighbouring kings, including the Chandela ruler Paramardi in 1182–83, although he could not annex the Chandela territory to his kingdom.[59] In 1191, he defeated the Ghurid king Muhammad of Ghor at the first Battle of Tarain. However, the next year, he was defeated at the second Battle of Tarain, and subsequently killed.[60]

.jpg/440px-Prithvi_Raj_Chauhan_(Edited).jpg)

Muhammad of Ghor appointed Prithviraja's son Govindaraja IV as a vassal. Prithviraja's brother Hariraja dethroned him, and regained control of a part of his ancestral kingdom. Hariraja was defeated by the Ghurids in 1194. Govindaraja was granted the fief of Ranthambore by the Ghurids. There, he established a new branch of the dynasty.[61]

Cultural achievements

The Chahamanas commissioned a number of Hindu temples, several of which were destroyed by the Ghurid invaders after the defeat of Prithviraja III.[62] Multiple Chahamana rulers contributed to the construction of the Harshanatha temple, which was probably commissioned by Govindaraja I.[63] According to Prithviraja Vijaya:

- Simharaja commissioned a large Shiva temple at Pushkar[64]

- Chamundaraja commissioned a Vishnu temple at Narapura (modern Narwar in Ajmer district)[65]

- Prithviraja I built a food distribution centre (anna-satra) on the road to Somnath temple for pilgrims.[66]

- Someshvara commissioned a number of temples, including five temples in Ajmer.[67][68]

Vigraharaja IV was known for his patronage to arts and literature, and himself composed the play Harikeli Nataka. The structure that was later converted into the Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra mosque was constructed during his reign.[69]

Chahamana dynasty of Naddula (c. 950–1197 CE)

The Chahamanas of Naddula, also known as the Chauhans of Nadol, were an Indian dynasty. They ruled the Marwar area around their capital Naddula (present-day Nadol in Rajasthan) between 10th and 12th centuries. The Chahamanas of Naddula were an offshoot of the Chahamanas of Shakambhari. Their founder was Lakshmana (alias Rao Lakha) was the son of the 10th century Shakambari ruler Vakpatiraja I. His brother Simharaja succeeded their father as the Shakambhari ruler.[70] The subsequent rulers fought against the neighbouring kingdoms of the Paramaras of Malwa, the Chaulukyas, the Ghaznavids,.[71] The last ruler Jayata-simha was probably defeated by Qutb al-Din Aibak in 1197.[72]

Chahamana dynasty of Jalor (c. 1160–1311 CE)

The Chahamanas of Jalor, also known as the Chauhans of Jalor in vernacular legends, were an Indian dynasty that ruled the area around Jalore in present-day Rajasthan between 1160 and 1311. They branched off from the Chahamanas of Naddula, and then ruled as feudatories of the Chaulukyas of Gujarat. For a brief period, they became independent, but ultimately succumbed to the Delhi Sultanate at the Siege of Jalore.

The Chahamanas of Jalor descended from Alhana, a Chahamana king of the Naddula branch. Originally, the Jalore Fort was controlled by a branch of the Paramaras until early 12th century. The Chahamanas of Naddula seized its control during Alhana's reign. Kirtipala, a son of Alhana, received a feudal grant of 12 villages from his father and his brother (the crown-prince) Kelhana. He controlled his domains from Suvarnagiri or Sonagiri, the hill on which Jalore Fort is located. Because of this, the branch to which he belonged came to be known as Sonagara.[73]

Chahamana dynasty of Ranastambhapura (c. 1192–1301 CE)

The Chahamanas of Ranastambhapura were a 13th-century Indian dynasty. They ruled the area around their capital Ranastambhapura (Ranthambore) in present-day Rajasthan, initially as vassals of the Delhi Sultanate, and later as sovereigns. They belonged to the Chahamana[disambiguation needed] (Chauhan) clan, and are also known as Chauhans of Ranthambore in vernacular Rajasthani bardic literature.

The Chahamana line of Ranastambhapura was established by Govindaraja, who agreed to rule as a vassal of the Ghurids in 1192, after they defeated his father, the Shakambhari Chahamana king Prithviraja III. Govindaraja's descendants gained and lost their independence to the Delhi Sultanate multiple times during the 13th century. Hammira, the last king of the dynasty, adopted an expansionist policy, and raided several neighbouring kingdoms. The dynasty ended with his defeat against the Delhi Sultan Alauddin Khalji at the Siege of Ranthambore in 1301 CE.

Later Medieval Period (c. 1000–1568 CE)

Rajputs before and after Ghurid invasions

.jpg/440px-Prithvi_Raj_Chauhan_(Edited).jpg)

In the 12th century before Ghurid invasions much of the Indo-Gangetic Plain region were ruled by the Rajputs.[75] In 1191 Rajput king of Ajmer and Delhi Prithviraj Chauhan unified several Rajput states and defeat the invading Ghurid army near Tarain in First Battle of Tarain, however the Rajputs did not chase the Ghurids and let Mu'izz al-Din escape.[76] As a result, in 1192, Mu'izz al-Din return with an army of an estimated strength of 120,000 Turks, Afghans and Muslim allies and decisively defeated The Rajput Confederacy at Second Battle of Tarain, Prithviraj fled the battleground but was captured near the battle site and executed. The defeat of Rajputs in the battle begins a new chapter in Rajasthan and Indian history as it not only crush Rajput powers in Gangetic Plain but also firmly established a Muslim presence in northern India.[77] In the fatal battle Malesi a Kachwaha Rajput and ally of Prithviraj lead the last stand for the Rajputs against Ghurids and died fighting after Prithviraj tried to escape.[78]

Over the next four centuries there were repeated, though unsuccessful, attempts by the central power based in Delhi to subdue the Rajput states of the region. The Rajputs, however, despite common historical and cultural traditions, were never able to unite to inflict a decisive defeat on their opponents.[79]

The Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar led other kingdoms in its resistance to outside rule. Rana Hammir Singh, defeated the Tughlaq dynasty and recovered a large portion of Rajasthan. The indomitable Rana Kumbha defeated the Sultans of Malwa, Nagaur and Gujarat and made Mewar the most powerful Hindu kingdom in Northern India.

Rajputana under Rana Sanga

In 1508 Rana Sanga ascended the throne after a long struggle with his brothers. He was an ambitious king under whom Mewar reached its zenith in power and prosperity. Rajput strength under Rana Sanga reached its zenith and threatened to revive their powers again in Northern India.[81] He establish a strong kingdom from Satluj in Punjab in the north until Narmada River in south in Malwa after conquering Malwa and from Sindhu river in west until Bayana in the east. In his military career he defeated Ibrahim Lodhi at the Battle of Khatoli and manage to free most of Rajasthan along with that he establish his control over parts of Uttar Pradesh including Chandwar, he gave the part of U.P to his allies Rao Manik Chand Chauhan who later supported him in Battle of Khanwa.[82] After that Rana Sanga fought another battle with Ibrahim Lodhi known as Battle of Dholpur where again Rajput confederacy were victorious, this time following his victory Sanga conquered much of the Malwa along with Chanderi and bestowed it to one of his vassal Medini Rai. Rai ruled over Malwa with Chanderi as his capital.[83]

Sanga also invaded Gujarat with 50,000 Rajput confederacy joined by his three allies. He plundered the Gujarat sultanate and chased the Muslim army as far as capital Ahmedabad. He successfully annexed northern Gujarat and appointed one of his vassals to rule there. Following the victories over the sultans, he successfully established his sovereignty over Rajasthan, Malwa and large parts of Gujarat.[80] In his campaign of Gujarat the Rajputs destroyed around 200 mosques and burnt down several Muslim towns. According to Chaube the campaign was brutal, in which Rajputs kidnapped many Muslim women as captives and sold them in the markets of Rajasthan.[84]

According to Gopinath Sharma the campaign not only enhanced Sanga's fame but also due to the Rajputs' religious bigotry in Gujarat Sanga became an eyesore to Muslim.[85] After these victories, he united several Rajput states from Northern India to expel Babur from India and re-establish Hindu power in Delhi.[86] He advanced with an army of 100,000 Rajputs to expel Babur and to expand his territory by annexing Delhi and Agra.[87] The battle was fought for supremacy of Northern India between Rajputs and Mughals.[88] However the Rajput Confederation suffered a disastrous defeat at Khanwa due to Babur's superior leadership and modern tactics. The battle was more historic and eventful than First Battle of Panipat as it firmly established Mughal rule in India while crushing re-emerging Rajput powers. The battle was also earliest to use cannons, matchlocks, swivel guns and mortars to great use.[89]

The battle also marks the last time in medieval India where the Rajputs stood united against a foreign invader. Although the exact casualties are unknown, it is estimated that all Rajput Houses lost many of their close allies in the battle.[90]

Rana Sanga was removed from the battlefield in unconscious state from his vassals Prithviraj Singh I of Jaipur and Maldeo Rathore of Marwar. After regaining consciousness he took an oath to never return to Chittor until he defeated Babur and conquer Delhi. He also stopped wearing a turban and use to wrap up cloth over his head.[91] While he was preparing to wage another war against Babur he was poisoned by his own nobles who opposed another battle with Babur. He died in Kalpi in January 1528.[92]

After his defeat, his vassal Medini Rai was defeated by Babur at the Battle of Chanderi and Babur captured the capital of Rai kingdom Chanderi. Medini was offered Shamsabad instead of Chanderi as it was historically important in conquering Malwa but Rao refuse the offer and choose to die fighting. The Rajput women and children committed self-immolation to save their honour from the Muslim army. After the victory Babur capture Chanderi along with Malwa which was ruled by Rai.[93] However Babur gave control of Malwa to Ahmed Shah a descendant of Malwa Sultan whose entire Kingdom of Malwa was annexed by Sanga. In this way Babur reinstated Muslim rule in Malwa.[94]

Khanzadas of Mewat

The Mewat State, existing from 1372 to 1527, stood as a sovereign kingdom in South Asia with Alwar as its capital. Governed by the Khanzadas of Mewat, a Muslim Rajput dynasty originating from Rajputana, they traced their descent to Raja Sonpar Pal, a Yaduvanshi Rajput who embraced Islam during the Delhi Sultanate era. The Khanzadas, adherents of Sunni Islam, established a hereditary polity in Mewat, granted by Firuz Shah Tughlaq in 1372. Over time, they asserted their sovereignty until their rule's culmination in 1527. [95][96]

Raja Hasan Khan Mewati hailed from the same lineage that had governed the Mewat region for nearly two centuries, asserting his sovereignty as a king. Acknowledged by Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, as the leader of 'Mewat country,' Hasan Khan Mewati played a pivotal role in the Battle of Khanwa, where he led 5,000 allies alongside Rana Sanga as part of the Rajput Confederation against Babur's Mughal forces. Notably, he reconstructed the Alwar fort in the 15th century. [97][98]

In military campaigns, Raja Hasan Khan Mewati featured prominently in the First Battle of Panipat, supporting Ibrahim Lodi against Babur. Despite facing defeat, Hasan Khan Mewati remained resolute, aligning himself with Rana Sanga after Panipat to resist Babur's incursion into the region.

In the Battle of Khanwa, Raja Hasan Khan Mewati supported Rana Sanga against Babur, he took charge of the commander's flag after Rana Sanga's fall and led a formidable attack with his 12 thousand horse soldiers. Initially successful, they appeared to overpower Babur's forces. Tragically, during the battle, Hasan Khan Mewati succumbed to a fatal chest injury caused by a cannonball, marking the end of his life but leaving behind a legacy of bravery and resilience on the battlefield. [99]

Noteworthy titles in the Khanzada lineage include "Wali-e-Mewat" and the later "Shah-e-Mewat," introduced by Hasan Khan Mewati in 1505.

Modern Period (c. 1568–1947 CE)

Mughal invasions & Rajput resistance

The Mughal Emperor Akbar expanded the empire into Rajputana in the 16th century. He laid siege to Chittor and defeated the Kingdom of Mewar in 1568. He also laid siege to Ranthambore and defeated the forces of Surjan Hada in the same year.

Akbar also arranged matrimonial alliances to gain the trust of Rajput rulers. He himself married the Rajput princess Jodha Bai. He also granted high offices to a large number of Rajput princes, and maintained cordial relations with them, such as Man Singh, one of the navaratnas. However, some Rajput rulers were not ready to accept Akbar's dominance and preferred to remain independent. Two such rulers were Udai Singh of Mewar and Chandrasen Rathore of Marwar. They did not accept Akbar's supremacy and were at constant war with him. This struggle was continued by Rana Pratap, the successor of Udai Singh. His army met with Akbar's forces at the Battle of Haldighati where he was defeated and wounded. Since then he remained in recluse for twelve years and attacked the Mughals from time to time.

Mughal influence is seen in the styles of Rajput painting and Rajput architecture of the medieval period.

Rise of Jat Kingdoms

Jat Kingdom of Bharatpur (c. 1722–1948 CE)

Bharatpur State, also known as the Jat Kingdom of Bharatpur, and historically known as the Kingdom of Bharatpur, was a Hindu Kingdom in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent. It was ruled by the Sinsinwar clan of the Hindu Jats. At the time of the reign of King Suraj Mal (1755–1763), the revenue of the state was 17,500,000 rupees per year.[100]

The formation of the state of Bharatpur was a result of revolts by the Jats living in the region around Delhi, Agra, and Mathura against the Mughals. Conflict between Jats and Rajputs for zamindari rights also complicated the issue, with Jats primarily being landowners, whereas Rajputs were primarily revenue collectors. The Jats put up a stiff resistance but by 1691, Raja Ram Sinsini and his successor Churaman were compelled to submit to the Mughals. Rajaram who also exhumed and burned the remains of Akbar is known for setting up a small fort at Sinsini. It was the key foundation of this kingdom.[101]

The most prominent ruler of Bharatpur was Maharaja Suraj Mal. He captured the important Mughal city of Agra on 12 June 1761. He also melted the two silver doors of the famous Mughal monument Taj Mahal. Agra remained in the possession of Bharatpur rulers till 1774. After Maharaja Suraj Mal's death, Maharaja Jawahar Singh, Maharaja Ratan Singh and Maharaja Kehri Singh (minor) under resident ship of Maharaja Nawal Singh ruled over Agra Fort.[103]

Jat Kingdom of Dholpur (c. 1806–1949 CE)

Historically known as the Kingdom of Dholpur, was a kingdom of eastern Rajasthan, India, which was founded in AD 1806 by a Jat ruler Rana Kirat Singh of Gohad. After 1818, the state was placed under the authority of British India's Rajputana Agency. The Ranas ruled the state until the independence of India in 1947, when the kingdom was merged with the Union of India.[104][105]

Very little is known of the early history of the state. According to tradition a predecessor state was established as Dhavalapura. In 1505 neighboring Gohad State of Rana Jats was founded and between 1740 and 1756 Gohad occupied Gwalior Fort. From 1761 to 1775 Dholpur was annexed to Bharatpur State and between 1782 and December 1805 Dholpur was again annexed by Gwalior. On 10 January 1806 Dholpur became a British protectorate and in the same year the Ruler of Gohad merged Gohad into Dholpur.[39][17]

Maratha influences (c. 1720–1817 CE)

Since the 1720s, the Maratha Empire began expanding northwards, led by Peshwa Baji Rao I of Pune.[106] This expansion finally brought the newly founded Maratha Empire in contact with the Rajputs. Some Rajput Kingdoms willingly accepted Maratha suzerainty, while others held some resistance. Rajasthan witnessed several campaigns by the Marathas, mostly under military leadership of Holkars and Scindhias.[107]

British influences (c. 1817–1947)

The arrival of the British East India Company in the region led to the administrative designation of some geographically, culturally, economically and historically diverse areas, which had never shared a common political identity, under the name of the Rajputana Agency. This was a significant identifier, being modified later to Rajputana Province and lasting until the renaming to Rajasthan in 1949. The Company officially recognized various entities, although sources disagree concerning the details, and also included Ajmer-Merwara, which was the only area under direct British control. Of these areas, Marwar and Jaipur were the most significant in the early 19th century, although it was Mewar that gained particular attention from James Tod, a Company employee who was enamoured of Rajputana and wrote extensively, if often uncritically, of the people, history and geography of the Agency as a whole.

Alliances were formed between the Company and these various princely and chiefly entities in the early 19th century, accepting British sovereignty in return for local autonomy and protection from the Marathas and Pindari depredations. Following the Mughal tradition and more importantly due to its strategic location Ajmer became a province of British India, while the autonomous Rajput states, the Muslim state of Tonk, and the Jat states of Bharatpur, Dholpur were organized into the Rajputana Agency.

In 1817–1818, the British Government concluded treaties of alliance with almost all the states of Rajputana. Thus began the British rule over Rajasthan, then called Rajputana.

- British Princely States of the Rajputana Agency are:

- Jaisalmer State

- Bikaner State

- Jodhpur State

- Jaipur State

- Udaipur State

- Alwar State

- Kishangarh State

- Dungarpur State

- Sirohi State

- Banswara State

- Kota State

- Bundi State

- Bharatpur State

- Karauli State

- Dholpur State

These states later merged in 1948 in seven phases to form the present state of Rajasthan in 1956.

Post-independence (c. 1947–present)

.jpg/440px-Nehru_with_Manik_Lal_Verma_(April_1948).jpg)

The name of Rajasthan as Rajputana became more pronounced or Popular in 12th century before Ghurid invasions, also Rajput as a separate caste emerge in Indian social structure around that time in 12th century.[75] The State was formed on 30th March 1949 when Rajputana – name as adopted by the British Crown was merged into the Dominion of India. After India's independence, the word Rajasthan for this state was constitutionally recognized on January 26, 1950, on the recommendation of the P. Satyanarayana Rao Committee.

Jaipur being the largest city was declared as capital of the state. Jaipur was founded in 1727 by the Kacchawa ruler of Amer Jai Singh II, after whom the city is named. During the British colonial period, the city served as the capital of Jaipur State. After independence in 1947, Jaipur was made the capital of the newly formed state of Rajasthan.[108]

Unification of Rajasthan

It took seven stages to form Rajasthan as defined today.

First Stage

In March 1948 the "Matsya Union" consisted of Alwar, Bharatpur, Dhaulpur and Karauli was formed.

Second Stage

Also, in March 1948 Banswara, Bundi, Dungarpur, Jhalawar, Kishangarh, Kota, Pratapgarh, Shahpura and Tonk joined the Indian union and formed a part of Rajasthan.

Third Stage

In April 1948 Udaipur joined the state and the Maharana of Udaipur was made Rajpramukh. Therefore, in 1948 the merger of south and southeastern states was almost complete.

Fourth Stage

Still retaining their independence from India were Jaipur State and the desert kingdoms of Bikaner, Jodhpur, and Jaisalmer. From a security point of view, it was claimed that it was vital to the new Indian Union to ensure that the desert kingdoms were integrated into the new nation. The princes finally agreed to sign the Instrument of Accession, and the kingdoms of Bikaner, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Jaipur acceded in March 1949. This time, the Maharaja of Jaipur, Man Singh II, was made the Rajpramukh of the state and Jaipur became its capital. 'March 30' is celebrated across the state to mark the formation of the state of Rajasthan.

Fifth Stage

Later in 1949, the United States of Matsya, comprising the former kingdoms of Bharatpur, Alwar, Karauli and Dholpur, was incorporated into Rajasthan.

Sixth Stage

On January 26, 1950, 18 states of united Rajasthan merged with Sirohi to join the state leaving Abu and Dilwara to remain a part of Greater Bombay and now Gujarat.

Seventh Stage

In November 1956, under the provisions of the States Re-organisation Act, the erstwhile part 'C' state of Ajmer, Abu Road Taluka, former part of Sirohi princely state (which were merged in former Bombay), State and Sunel-Tappa region of the former Madhya Bharat merged with Rajasthan and Sironj sub district of Jhalawar was transferred to Madhya Pradesh. Thus giving the existing boundary Rajasthan. Today with further reorganisation of the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar. Rajasthan has become the largest state of the Indian Republic. The unification of Rajasthan completed in 1 November 1956.

First Government of Rajasthan

Gurumukh Nihal Singh was appointed as first governor of Rajasthan. Hiralal Shastri was the first nominated chief minister of the state, taking office on 7 April 1949. He was succeeded by two other nominated holders of the office before Tika Ram Paliwal became the first elected chief minister from 3 March 1951.

Contemporary Rajasthan

During the Second India–Pakistan War, in September 1965, Pakistan initiated the Rajasthan Front and seized many areas of Rajasthan from India. Later they were returned as per the Tashkent Declaration. The princes of the former kingdoms were constitutionally granted handsome remuneration in the form of privy purses and privileges to assist them in the discharge of their financial obligations. In 1970, Indira Gandhi, who was then the Prime Minister of India, commenced under-takings to discontinue the privy purses, which were abolished in 1971. Many of the former princes still continue to use the title of Maharaja, but the title has little power other than as a status symbol. Many of the Maharajas still hold their palaces and have converted them into profitable hotels, while some have made good in politics. The democratically elected Government runs the state with a chief minister as its executive head and the governor as the head of the state.

Development of Administration

Currently, including the new district of Pratapgarh, there are 50 districts, 105 sub-divisions, 37,889 villages, 350+ tehsils and 222 towns in Rajasthan.

On 17 March 2023, Government of Rajasthan announced the creation of 19 new districts and 3 new divisions, while Jaipur district and Jodhpur district would cease to exist (becoming Jaipur Urban, Jaipur rural, Jodhpur urban, and Jodhpur rural), thus number of districts was increased to 50 and divisions to 10.

See also

- Matsya Kingdom

- Outline of Rajasthan

- List of Rajput dynasties

- List of battles of Rajasthan

- Timeline of history of Rajasthan

- List of dynasties and rulers of Rajasthan

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ Frontiers of the Indus Civilization

- ^ Gupta, Kunj Bihari Lal (1969). The Evolution of Administration of the Former Bharatpur State, 1722-1947. Vidya Bhawan. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Tod, James (1899). The Annals and Antiquities of Rajastʾhan: Or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India. Indian Publication Society. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ General, India Office of the Registrar (1975). Census of India, 1971: Series 1: India. Manager of Publications. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Rajasthan Through the Ages Vol 1 Bakshi S. R."

- ^ Sarkar 1994, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3.

- ^ Daniel Hillel (2016), Advances in Irrigation, Elsevier, p. 132, ISBN 978-1-4832-1527-3

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 16, p. 156.

- ^ Calkins, PB; Alam M. "India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ Lal, BB (2002). "The Homeland of Indo-European Languages and Culture: Some Thoughts". Purātattva. Indian Archaeological Society. pp. 1–5.

- ^ Hooja, Rima. "The Transition to Food Production." In A History of Rajasthan, 206-08. New Delhi: Rupa, 2006

- ^ Joshi, M.C, ed. "Indian Archaeology: 1987-88 A Review." Archaeological Survey of India, 1992, 101-02. Accessed 7 March 2018. asi.nic.in/nmma_reviews/Indian Archaeology 1987-88 A Review.pdf

- ^ Bhan, Suraj (1 December 2006). "North Indian Protohistory and Vedic Aryans". Ancient Asia. 1: 173. doi:10.5334/aa.06115. ISSN 2042-5937.

- ^ a b "Integration of Rajasthan". Rajasthan Legislative Assembly website. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (14 July 2017), "Hinduism and its basic texts", Reading the Sacred Scriptures, New York: Routledge, pp. 250, 157–170, doi:10.4324/9781315545936-11, ISBN 978-1-315-54593-6, archived from the original on 3 July 2023, retrieved 16 September 2020

- ^ a b Malik, Dr Malti (2016). History of India. New Saraswati House India Pvt Ltd. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-81-7335-498-4. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ Ratnawat, Shyam Singh. Sharma, Krishna Gopal. (1999). History and culture of Rajasthan : from earliest times upto 1956 A.D. Centre for Rajasthan Studies, University of Rajasthan. p. 7. OCLC 606486051. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "States of India since 1947". Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "History of Legislature in Rajasthan". Rajasthan Legislative Assembly website. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ R. C. Majumdar 1977, p. 298-299

- ^ Chaurasia 2002a, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Mishra 1966, p. 3.

- ^ Puri 1957, p. 20.

- ^ Chaurasia 2002a, p. 207.

- ^ Dikshit, R. K. (1976). The Candellas of Jejākabhukti. Abhinav. p. 72. ISBN 9788170170464.

- ^ Mitra, Sisirkumar (1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9788120819979.

- ^ Kala, Jayantika (1988). Epic scenes in Indian plastic art. Abhinav Publications. p. 5. ISBN 978-81-7017-228-4.

- ^ Kalia 1982, p. 2.

- ^ Bajpai, K. D. (2006). History of Gopāchala. Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- ^ Sinha 1991, p. 64.

- ^ Sinha 1991.

- ^ Sinha 1991, p. 66.

- ^ Majumdar 1977, p. 299.

- ^ Somani 1976, p. 34.

- ^ a b Somani 1976, p. 36.

- ^ Somani 1976, p. 40.

- ^ Chakravarti 1987, pp. 119–121; Banerjee 1958, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Hooja, Rima (2006). A history of Rajasthan. Rupa. pp. 328–329. ISBN 9788129108906. OCLC 80362053. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ The Rajputs of Rajputana: a glimpse of medieval Rajasthan by M. S. Naravane ISBN 81-7648-118-1

- ^ Manoshi, Bhattacharya (2008). The Royal Rajputs. Rupa & Company. pp. 42–46. ISBN 9788129114013.

- ^ Singh, K. S. (1998). India's communities. Oxford University Press. p. 2211. ISBN 978-0-19-563354-2. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Praagh, David Van (27 October 2003). Greater Game: India's Race with Destiny and China by David Van Praagh. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 9780773571303. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Judge (13 March 2014). Mapping social exclusion in India: Caste, Religion, and Borderlands. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107056091. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ a b Beny & Matheson, p. 51.

- ^ Singh, Ganda (1990). Sardar Jassa Singh Ahluwalia. Punjabi University. pp. 1–4. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 14, page 2 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library". Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Khaliq, Fazal (1 February 2017). "Derawar Fort: a 9th century human marvel on the verge of collapse". Dawn. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

The Derawar Fort was first built in the 9th century under the kingship of Rai Jajja Bhutta, a Hindu Rajput from Jaisalmir in India's Rajasthan state.

- ^ Derawar Fort – Living to tell the tale, Dawn, 20 June 2011, archived from the original on 8 December 2021, retrieved 25 November 2021

- ^ a b "Dawn News". Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Beny & Matheson, p. 147.

- ^ Martinelli and Michell, p. 239.

- ^ Memoranda on the Indian States. Government Of India. 1939. pp. 110–139.

- ^ Sarda 1935, p. 217.

- ^ Sarda 1935, p. 224.

- ^ Sarda 1935, p. 225.

- ^ Singh 1964, pp. 131–132; Sharma 1959, p. 40.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 140-141.

- ^ Talbot 2015, pp. 39.

- ^ Khan 2008, p. xvii.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 221.

- ^ Sharma 1959, p. 87.

- ^ Sharma 1959, p. 26.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 104.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 124.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 128.

- ^ Sharma 1959, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 159.

- ^ Talbot 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Singh 1964, p. 233.

- ^ Sen 1999, p. 334.

- ^ Singh 1964, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Srivastava 1979, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Sarkar 1960, pp. 32–35.

- ^ a b Sarkar 1960, pp. 32.

- ^ Sarkar 1994, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Sarkar 1960, pp. 37.

- ^ Sarkar 1960, p. 32,34.

- ^ "History of Rajasthan". Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b Sharma 1954, p. 18.

- ^ "History of Rajasthan by Deryck O.Lodrick". Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Sharma 1954, p. 17.

- ^ Chaurasia 2002b, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Chaube 1975, pp. 132–139.

- ^ Sharma 1954, pp. 15.

- ^ Sharma 1954, p. 19.

- ^ Spear 1990, pp. 23.

- ^ Sharma 1954, p. 8.

- ^ Rao 1991, p. 453-454.

- ^ Sarkar 1994, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Sharma 1954, pp. 43.

- ^ Sharma 1954, pp. 44.

- ^ Chaurasia 2002b, p. 157.

- ^ Chaurasia 2002b, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Bharadwaj, Suraj (2016). State Formation in Mewat Relationship of the Khanzadas with the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal State, and Other Regional Potentates. Oxford University Press. p. 11. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Meo Rajput by Sardar Azeemullah Khan Meo". www.jadeed.store. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (1 April 1982), "Mughal India", The Cambridge Economic History of India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 458–471, doi:10.1017/chol9780521226929.027, ISBN 978-1-139-05451-5, retrieved 7 November 2023

- ^ "Tareekh-e-Miyo Chhatri by Hakeem Abdush Shakoor". Rekhta. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "अलवर का वीर देशभक्त सपूत, जिससे बाबर भी घबराता था, बाबर के खिलाफ जमकर किया था युद्ध | Hasan Khan Mewati Alwar Story In Hindi". Patrika News (in Hindi). 18 December 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Dube, V. S.; Misra, M. L. (January 1944). "Galena Deposit of Jotri, Bharatpur State". Transactions of the Indian Ceramic Society. 3 (1): 81–83. doi:10.1080/0371750x.1944.11012048. ISSN 0371-750X. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Bhatia, O. P. Singh (1968). History of India, from 1707 to 1856. Surjeet Book Depot. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ R.C.Majumdar, H.C.Raychaudhury, Kalikaranjan Datta: An Advanced History of India, fourth edition, 1978, ISBN 0-333-90298-X, Page-535

- ^ "Taj Mahal". MANAS. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Dholpur: History, Geography, Places to See". RajRAS | RAS Exam Preparation. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 11, p. 323". dsal.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Maratha Rajputs Relations, History of Rajasthan". Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Naravane, M. S. (1999). The Rajputs of Rajputana: A Glimpse of Medieval Rajasthan. APH. ISBN 9788176481182. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ Sarkar 1994, pp. 22.

Bibliography

- Banerjee, Anil Chandra (1958). Medieval studies. A. Mukherjee & Co. OCLC 4469888.

- Bhatnagar, V. S. (1991). Kanhadade Prabandha: India's greatest patriotic saga of medieval times: Padmanābha's epic account of Kānhaḍade. New Delhi: Voice of India. Primary source.

- Chakravarti, N. P. (1987) [1958]. "Appendix: Rajaprasasti Inscription of Udaipur (Continued from Vol. XXIX, Part V)". In N. Lakshminarayan Rao; D. C. Sircar (eds.). Epigraphia Indica. Vol. XXX. Archaeological Survey of India.

- Chaube, J. (1975). History of Gujarat Kingdom, 1458–1537. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 9780883865736. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002a). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002b). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.

- Cort, John E. (1998). Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791437865.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810864016. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Kalia, Asha (1982). Art of Osian Temples: Socio-economic and Religious Life in India, 8th–12th Centuries A.D. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9780391025585.

- Majumdar, R. C. (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804364. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Mishra, Vibhuti Bhushan (1966). The Gurjara-Pratīhāras and Their Times. S. Chand. OCLC 3948567. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Mitter, Partha (2001). Indian Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284221-3. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Puri, Baij Nath (1957). The history of the Gurjara-Pratihāras. Munshiram Manoharlal. OCLC 2491084.

- Rao, K. V. Krishna (1991). Prepare Or Perish: A Study of National Security. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7212-001-6. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Sarda, Har Bilas (1935). Speeches And Writings Har Bilas Sarda. Ajmer: Vedic Yantralaya.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1960). Military History of India. Orient Longmans. ISBN 9780861251551.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1994). A History of Jaipur: C. 1503–1938. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0333-5. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 9788122411980. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Sharma, Dasharatha (1959). Early Chauhān Dynasties. S. Chand / Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0618-9. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Sharma, Gopinath (1954). Mewar & the Mughal Emperors (1526–1707 A.D.). S.L. Agarwala. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Sharma, G. N.; Bhatnagar, V. S.; University of Rajasthan (1992). The Historians and sources of history of Rajasthan. Jaipur: Centre for Rajasthan Studies, University of Rajasthan.

- Singh, R. B. (1964). History of the Chāhamānas. N. Kishore. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Sinha, Nandini (1991). "A Study of the Origin Myths Situating the Guhilas in the History of Mewar (A.D. Seventh to Thirteenth Centuries)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 52. Indian History Congress: 63–71. JSTOR 44142569.

- Somani, Ram Vallabh (1976). History of Mewar, from Earliest Times to 1751 A.D. Mateshwari. OCLC 2929852. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Spear, Percival (1990). A History of India. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-0138368-. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Srivastava, Ashok Kumar (1979). The Chahamanas of Jalor. Sahitya Sansar Prakashan. OCLC 12737199.

- Talbot, Cynthia (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118560.

Further reading

- Gupta, R. K.; Bakshi, S. R. (2008), Studies In Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages: The Heritage Of Rajputs, vol. 1, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 9788176258418