History of Inuit clothing

Archaeological evidence indicates that the use of Inuit clothing extends far back into prehistory, with significant evidence to indicate that its basic structure has changed little since. The clothing systems of all Arctic peoples (encompassing the Inuit, Iñupiat, and the indigenous peoples of Siberia and the Russian Far East) are similar, and evidence in the form of tools and carved figurines indicates that these systems may have originated in Siberia as early as 22,000 BCE, and in northern Canada and Greenland as early as 2500 BCE. Pieces of garments found at archaeological sites, dated to approximately 1000 to 1600 CE, are very similar to garments from the 17th to mid-20th centuries, which confirms consistency in the construction of Inuit clothing over centuries.

Beginning in the late 1500s, contact with non-Inuit traders and explorers began to have an increasingly large influence on the construction and appearance of Inuit clothing. Imported tools and fabrics became integrated into the traditional clothing system, and premade fabric garments sometimes replaced traditional wear. Adoption of fabric garments was often driven by external pressure to conform to non-Inuit standards of dress, but many Inuit also adopted fabric garments for their own convenience. These voluntary adoptions were often a precursor to the decline or disappearance of traditional styles.

With an increase in cultural assimilation and modernization at the beginning of the 20th century, the production of traditional skin garments for everyday use declined as a result of loss of skills combined with shrinking demand. Formal schooling, particularly during the era of the Canadian Indian residential school system, was destructive to the ongoing cycle of Inuit elders passing down knowledge to younger generations. Wider availability of manufactured clothing and reduced availability of animal pelts further reduced demand for traditional clothing. The combination of these factors resulted in a near-complete loss of traditional clothing-making skills by the 1990s.

Since that time, Inuit groups have made significant efforts to preserve traditional skills and reintroduce them to younger generations in a way that is practical for the modern world. Although full outfits of traditional skin clothing are uncommon overall, they are still seen in the winter and on special occasions. Many Inuit seamstresses today use modern materials to make traditionally-styled garments, leading to the growth of an Inuit-led fashion movement, a subset of Indigenous American fashion. In light of the growing interaction between Inuit clothing and the fashion industry, Inuit groups have raised concerns about the protection of Inuit heritage from cultural appropriation and prevention of genericization of cultural garments like the amauti.

Prehistoric development

Archaeological research on Inuit clothing provides a great deal of insight into the origins of skin clothing system. Individual skin garments are rarely found intact at archaeological sites, as animal hide is highly susceptible to decay, so it is difficult to definitively date the origins of circumpolar skin clothing. Evidence for the earliest origins of the Inuit clothing system is therefore usually inferred from sewing tools and art objects found at archaeological sites.[1]

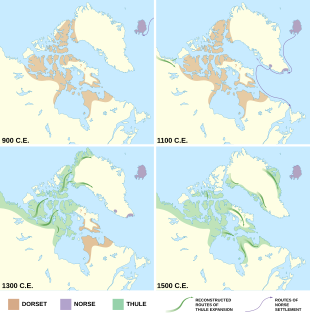

In what is now Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, archaeologists have found carved figurines and statuettes at sites originating from the Mal'ta–Buret' culture which appear to be wearing tailored skin garments, although these interpretations have been contested. The age of these figurines indicates that a clothing system similar to that of the Inuit may have been in use in Siberia as early as 22,000 BCE.[2] Prehistoric ivory figurines from the Dorset culture, a Paleo-Inuit culture that lived in what is now northern Canada from approximately 500 BCE to 1500 CE, also appear to show parkas, underpants, and Inuit boots (kamiit).[a][4] Some of these Dorset figures exhibit what appear to be high collars rather than hoods, and it is not clear whether they depict figures with hoods down, or if the parkas worn in that era had no hoods at all.[5]

Tools for skin preparation and sewing made from stone, bone, and ivory, found at prehistoric archaeological sites and consistent with later tools used by the Inuit, confirm that skin clothing was being produced in northern regions of North America and Greenland as early as 2500 BCE.[6][7] Conversely, the absence of sewing needles at summertime coastal camps indicates that the Dorset may have had taboos forbidding the production of caribou clothing at coastal sites, just as the later Inuit did.[8] Archaeological evidence of seal processing by the Dorset culture has been found at Philip's Garden in the Port au Choix Archaeological Site in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Radiocarbon dating indicates use of the site spanned approximately eight centuries, from about 50 BCE at the earliest to about 770 CE at the latest.[b][9]

Figurines from the Thule culture era of approximately 1000 to 1600 CE found at archaeological sites in Nunavut, Canada also display features consistent with skin clothing. One ivory figure from Southampton Island displays chest straps reminiscent of the woman's parka, the amauti. A wooden figurine from Ellesmere Island actually has miniature trousers made of bear skin, a feature which Inuit skin clothing expert Betty Kobayashi Issenman noted was, to her knowledge, completely unique on prehistoric figurines.[10] Thule-era ivory figurines collected in Igloolik in 1939 show the large hoods characteristic of the amauti, as well as the rounded tails of women's parkas.[11]

Occasionally, scraps of frozen skin garments or even whole garments are found at archaeological sites. It can be difficult to determine the era of origin owing to the delicacy of these items. Some are believed to come from the Dorset culture era, but the majority are believed to be from the Thule culture era of approximately 1000 to 1600 CE.[12][13] Although style elements like hood height and flap size have changed, structural elements like patterns, seam positions, and stitching of these remnants and outfits are very similar to garments from the 17th to mid-20th centuries, which confirms significant consistency in construction of Inuit clothing over centuries.[14] For example, one Dorset-era boot sole from Kimmirut (formerly Lake Harbour), Nunavut, dated to 200 CE, is constructed with an identical style to modern boots.[13]

Thule-era garments are similarly consistent with later items, which suggests that the Inuit skin clothing system directly evolved from the Thule system.[11] At Devon Island in Nunavut, Canada, several pieces of frozen skin clothing were found in an archaeological dig conducted in 1985; these items, including an intact child's mitten, have been dated to the early Thule era, around 1000 CE.[15] The pattern and stitching of these garments matches those of modern garments.[16] Clothing items including a kamleika, a type of overcoat made of gut-skin, were found at a dig site on Ellesmere Island in 1978. They have been dated to 1200 CE, and are consistent with 20th century gut-skin coats.[10] A group of eight well-preserved and fully dressed mummies were found at Qilakitsoq, an archaeological site on Nuussuaq Peninsula, Greenland, in 1972. They have been carbon-dated to c. 1475, and extensive research on these garments indicates that they were prepared and sewn in the same manner as modern skin clothing from the Kalaallit people of the region.[17] Archaeological digs in Utqiaġvik, Alaska from 1981 to 1983 uncovered the earliest known samples of caribou and polar bear skin clothing of the Kakligmiut group of Iñupiat, dated to approximately 1510–1826.[18] The construction of these garments indicates that Kakligmiut garments underwent little change between approximately 1500–1850.[19][20]

As a result of socialization and trade, Inuit groups throughout their history incorporated clothing designs and styles between themselves, as well as from other Indigenous Arctic peoples such as the Chukchi, Koryak, and Yupik peoples of Siberia and the Russian Far East, the Sámi people of Scandinavia, and various non-Inuit North American Indigenous groups.[21][22] There is evidence indicating that prehistoric and historic Inuit gathered in large trade fairs to exchange materials and finished goods; the trade network that supported these fairs extended across some 3,000 km (1,900 mi) of Arctic territory.[23]

European contact

Due to a lack of records, it is difficult to pin down the earliest point of contact between Europeans and the Inuit. The Norse had colonies in Greenland from 986 to around 1410, and the Thule began migrating there from North America as early as 800; contact between the groups is believed to have occurred after 1150.[24][25] Historical records and archaeology indicate that the groups traded as well as fought, and that the Norse did not appear to adopt garments or hunting techniques from the Inuit, who they called skrælings.[26]

Europeans had little contact with the Inuit in the following centuries. Occasionally, sailors would kidnap Inuit from what is now Labrador and bring them to Europe to be exhibited and studied. The Europeans conducting these exhibitions sometimes produced images and written records of their captives, particularly their clothing. The earliest known European depictions of living Inuit were advertising broadsides printed in Germany in 1567, which depict an anonymous Inuit woman and her child who had been kidnapped from Labrador in 1566.[27]

The first real expansion of contact with the Inuit was prompted by the voyages of Martin Frobisher, who from 1576 to 1578 made several attempts to seek the Northwest Passage in the North American Arctic, necessitating contact with the Inuit. Subsequently, hundreds of European ships arrived to hunt seals and whales, trade with the Inuit, and continue the search for the Northwest Passage.[28] Europeans continued to document the details of Inuit clothing during this time, producing the first detailed visual records of Inuit garments. The clothing styles they depict are largely consistent throughout the centuries. For example, Issenman notes that the 1567 broadsides are consistent with a 1654 painting depicting Kalaallit Inuit in traditional skin clothing.[27] In turn, the Kalaallit clothing in that image is similar to that found with the bodies at Qilakitsoq.[29]

After the arrival of Frobisher and his imitators, contact with non-Inuit, especially traders and explorers from America, Europe, and Russia, began to have a greater influence on the construction and appearance of Inuit clothing.[30] Clothing-related items brought by foreigners include trade goods like steel needles and fabric as well as pre-made European garments.[31] While imported garments never fully replaced the traditional clothing complex of the Inuit, they did gain a significant degree of traction in many areas.[32] Figures carved by Inuit following contact include details that indicate the wide adoption of fabric clothing.[4]

Christian missionaries played a significant part in influencing Inuit communities to adopt non-Inuit or "Southern" clothing.[33] Missionaries imposed a religious taboo on nudity where none existed before. Women's clothing was seen as particularly inappropriate, as the cut of certain garments could expose their trousers or even their bare thighs, so they were often pressured into wearing long skirts or dresses to conceal their legs.[34][35][36] Adoption of Southern clothes, especially formalwear such as coats and ties, was taken as a visual signifier of conversion to Christianity.[37]

International trade, particularly in the form of the fur trade and the whaling industry, was also implicated in unwanted changes to Inuit clothing. After establishing a trading post on Kodiak Island, Alaska, in 1783, Russian traders prevented the Inuit there from using sea otter and bear pelts for traditional garments, preferring to sell these valuable pelts internationally.[38] Similarly, in the mid-1800s, Inuit in West Greenland began to sell their pelts rather than making clothes from them, as the newly introduced cash economy made their previous subsistence lifestyle difficult to maintain.[39] After the expansion of the whaling industry in the Canadian Arctic around the middle of the 19th century, many Inuit men took jobs on whaling ships.[31] The whaling season extended through the fall until November, overlapping the traditional hunting season for caribou. As a result, many men who worked on whalers were unable to secure enough caribou skins to make appropriate winter clothing, which in turn limited their ability to hunt in the winter, sometimes leading to the starvation of their families.[40]

Purposeful adoption of foreign garments

Although much of the drive towards adoption of foreign garments around this time came from external pressure, many Inuit also adopted foreign materials and garments on their own initiative, trading or purchasing for ready-made fabric and clothing. In Canada, these items mostly came from the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), and in Greenland, from the Royal Greenland Trading Department (RGTD).[41][42][43] Men in particular embraced ready-made cloth garments more readily than women, as suitable foreign equivalents were available for most men's clothing.[44] In Greenland, many Inuit men readily adopted lopapeysa, traditional Icelandic sweaters.[45] Men from the Nunavimiut or Ungava Inuit group from Ungava Bay adopted crocheted woolen hats for beneath their hoods.[46] Most Inuit men working on whaling ships across the Arctic adopted cloth garments completely during the summer, generally retaining only their waterproof sealskin kamiit.[47][32]

While Inuit men easily adopted outside clothing, the women's amauti, specifically tailored to its function as a mother's garment, had no European ready-made equivalent. Instead, Inuit women used purchased cloth to create garments that suited their needs.[44] Beginning in the middle of the 19th-century, the Iñupiaq people of northern Alaska began to use colorful cotton fabrics like drill and calico to make over-parkas to protect their caribou garments from dirt and snow.[48][49] Men's were shorter while women's were calf-length with ruffled hems. In Iñupiaq these garments are called atikłuk, while in Inuktitut, spoken in Canada, they are called silapaaq.[50][51] The longer women's version eventually made its way eastward through the Mackenzie River delta in the Northwest Territories, where it became known as the cloth parka or Mother Hubbard parka (from the European Mother Hubbard dress).[48][50][49] The Mother Hubbard parka was originally worn with the fur amauti (overtop or underneath), but later styles were insulated with duffel cloth or fur and could be worn on their own, especially during summer.[52] These garments were valued by women as they were simple to make compared to the intensive process of making skin clothing. Their exotic materials were considered a sign of wealth and status.[32][48]

Voluntary adoptions of outside clothing styles were a precursor to the decline or disappearance of traditional styles in many areas. Inuit from disparate groups and tribes often mixed at camps and trading posts set up by European traders, trading their techniques and styles, which muted local differences in styles of clothing.[53][54] In the 1880s, the establishment of an RGTD trading post on the east coast of Greenland greatly increased the availability of foreign garments, which led to the simplification and decline of traditional Inuit skin garments in the area.[55] In 1914, the arrival of the Canadian Arctic Expedition in the territory of the previously-isolated Copper Inuit prompted the virtual disappearance of the unique Copper Inuit clothing style, which by 1930 was almost entirely replaced by a combination of styles imported by newly immigrated Inuvialuit and European-Canadian clothing, particularly the Mother Hubbard parka.[56] Although the Mother Hubbard only arrived there in the late 19th century, it largely eclipsed historical styles of clothing to the point where it is now seen as the traditional women's garment in those areas.[56][57]

Adoption of Inuit garments by non-Inuit

Cross-cultural adoption of clothing was hardly one-sided. During this period, non-Inuit whalers, missionaries, and explorers all made use of Inuit clothing, which was known to be extremely effective for the climate.[58][59][37] Social and economic factors also played a part in driving non-Inuit to adopt skin clothing.[60] Because there was less effort to colonize the Arctic regions with white settlers when compared to more temperate regions, some Europeans may have felt less social pressure to wear European clothing.[61] For others, adopting Inuit clothing signified their own prowess in surviving a difficult environment.[60][37] Inuit oral history records that some explorers, such as Graham Rowley, were known for wearing their skin garments poorly.[62]

European whalers sometimes adopted Inuit garments for Arctic travel, occasionally even going so far as to hire entire families of Inuit to travel with them and sew skin clothing.[58][63] Use of Inuit clothing reportedly reduced deaths from exposure on whaling ships.[59][64] By the mid-1800s, it was common for American and British polar explorers to trade for or commission Inuit garments.[59] Canadian explorers Diamond Jenness and Vilhjalmur Stefansson lived with the Inuit during the Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913–1916), adopting Inuit clothing and making in-depth studies of its construction.[64][65] The Scandinavian personnel of the Fifth Thule Expedition (1922–1924) did the same.[65]

Some explorers positioned their adoption of Inuit clothing as a marketing strategy to drive interest and funding for their expeditions.[60] Historian Sarah Pickman argues that famous polar explorers like Robert Peary, Roald Amundsen, and Robert Scott promoted their use or rejection of Inuit clothing as evidence of their own adventuring skill.[59] Peary, like many other explorers, sold photographs of himself in striking Inuit-style outfits and sometimes appeared at lectures wearing furs.[66] He often claimed that his use of Inuit technology was a unique factor in his success as an Arctic explorer, despite the fact that plenty of previous explorers had used Inuit technology.[67]

Adoption of Inuit clothing principles was instrumental in early exploration of Antarctica. Physician and explorer Frederick Cook had encountered Greenlandic Inuit as part of Peary's expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892, and believed that Inuit clothing and travel methods would be useful in Antarctica.[68] Like Peary, he toured the lecture circuit, dressing in furs to raise funds for an Antarctic expedition, although it never materialized.[69] He later brought skin garments he had commissioned to the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899, where he and Amundsen met and exchanged ideas about polar exploration.[70][71] When the Amundsen and Scott South Pole expeditions are compared, Amundsen's use of Inuit-style clothing is regarded as a significant factor in the success of his expedition, while Scott's preference for British textiles is considered a major failure point in his own.[72] Amundsen wrote that his detailed preparations, including his extensive study of the clothing of the Netsilingmiut Inuit, had been paramount in his success.[73] In contrast, Scott promoted his rejection of Inuit furs in favor of traditional British textile-based expedition gear as a point of nationalistic pride.[74]

Wearing skin clothing did not necessarily indicate respect for the Inuit and their practices.[59] Missionaries readily adopted Inuit clothing and wrote of its effectiveness, but their goal was to supplant Inuit culture with Christianity.[37] Many explorers continued to treat Inuit with condescension even as they appropriated their traditional garments.[59] Peary never learned more than a few words of Inuktitut despite his nearly twelve years in the Arctic, and wrote that Inuit were valuable assistants but "of course they could not lead".[67] Amundsen acknowledged Inuit mastery of polar survival skills, but wrote of them as "savages" and never included Inuit members in his expeditions.[75]

Decline since the nineteenth century

.jpg/440px-Inuitkvinder_skraber_rensdyrskind_-_Inuit_women_scraping_caribou_skin_(15143756777).jpg)

The production of traditional skin garments for everyday use has declined in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as a result of loss of skills combined with shrinking demand. Lifestyle change as a result of outside influence was a significant factor in the decline of skin clothing. This peaked in the 19th and 20th centuries when the presence of non-Inuit missionaries, researchers, explorers, and government officials significantly increased in Inuit communities.[76]

Few modern Inuit maintain the nomadic hunting-trapping lifestyle of their ancestors, instead spending much of their time indoors in heated buildings.[77] Many Inuit in Northern Canada work outdoor industrial jobs for which fur clothing, particularly kamiit, would be impractical.[78] Purchasing manufactured clothing saves time and energy compared to the intensive workload involved in making traditional skin clothing, and it can be easier to maintain.[79]

The introduction of the Canadian Indian residential school system to northern Canada, beginning with the establishment of Christian mission schools in the 1860s, was extremely destructive to the ongoing cycle of elders passing down knowledge to younger generations through informal means.[80][81] Children who were sent to residential schools or stayed at hostels to attend school outside their communities were often separated from their families for years, in an environment that made little to no attempt to include their language, culture, or traditional skills.[82] Children who lived at home and attended day schools were at school for long hours most days, leaving little time for families to teach them traditional clothing-making and survival skills.[83] Until the 1980s, most northern day schools did not include material on Inuit culture, compounding the cultural loss.[84][85] The time available for traditional skills was further reduced in areas of significant Christian influence, as Sundays were seen as a day of rest on which to attend church services, not to work.[86] Lacking the time and inclination to practice, many younger people lost interest in creating traditional clothing.[87]

The availability of pelts has also impacted the production of skin garments. In the early 20th century, overhunting led to a significant depletion of caribou herds in some areas.[88] Lack of materials after the 1940s caused the extinction of a style of baggy leggings or stockings worn by Iglulingmiut and Caribou Inuit.[89] Many areas today have restrictions on hunting that impacts the availability of pelts. Greenland, for example, requires a hunting license, limits the number of animals that can be hunted, and sets hunting seasons.[90] Climate change in Canada has resulted in decreasing seal populations and reduced availability of seal pelts.[91]

From the 1960s to the 1980s, strong opposition to seal hunting from the animal rights movement, particularly an influential 1976 Greenpeace Canada campaign, led to significant restrictions on the import of sealskin goods in the United States (1972) and the European Economic Community (1983).[c] These restrictions crashed the export market for seal pelts and caused a corresponding drop in hunting as a primary occupation, reducing the availability of pelts for northern seamstresses and increasing poverty and suicide rates among Inuit in Nunavut.[81][92][93] Income levels for Inuit dropped by a reported 95% compared to pre-ban levels.[94]

In the 1980s, the Greenlandic government launched a program to increase demand for sealskin products by subsidizing the purchase of sealskins from hunters and supporting the creation of new designs. The program has run at a deficit since it was established, as a result of the 1980s crash in sealskin prices.[95] Greenpeace Canada apologized to Inuit in 1985 for the knock-on effects of their campaign. The European Union ban on seal products was reaffirmed in 2009.[96][97] In 2015, exemptions were made in the ban for certified indigenous-hunted products, but a 2020 report described this exemption as economically ineffective.[98][99][97] The sealskin ban has never been repealed or loosened in the United States.[100] Many Inuit have criticized efforts to ban seal hunting and sealskin products as short-sighted and culturally ignorant.[81][101][102]

This combination of factors resulted in less demand for elders to create skin garments, which made it less likely that they would pass on their skills.[84] By the mid-1990s, the skills necessary to make Inuit skin clothing were in danger of being completely lost.[103][104] The decline in the use of traditional clothing coincided with an uptick in artistic depictions of traditional clothing in Inuit art, which has been interpreted as a reaction to a feeling of cultural loss.[105]

Contemporary revival of traditional clothing

.jpg/440px-Throat_singers_1999-04-07_(cut).jpg)

General revitalization efforts

Since the 1990s, Inuit groups have made significant efforts to preserve traditional skills and reintroduce them to younger generations in a way that is practical for the modern world. Many educational barriers to traditional knowledge have come down. By the 1990s, both the residential schools and the hostel system in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories had been abolished entirely.[d][106] In northern Canada, many schools at all stages of education have introduced courses which teach traditional skills and cultural material.[107]

Outside of the formal education system, cultural literacy programs such as Miqqut, Somebody's Daughter, Reclaiming our Sinew, and Traditional Skills Workshop, spearheaded by organizations like Pauktuutit (Inuit Women of Canada) and Ilitaqsiniq (Nunavut Literacy Council), have been successful in reintroducing modern Inuit to traditional clothing-making skills.[108][109] Sewing groups and classes are popular in northern communities, many featuring elders in their traditional teaching role.[110][111][112][113] Many museums now cooperate with Inuit communities in knowledge-sharing and training.[15]

On a technical level, modern-day techniques ease the time and effort needed for production, lowering barriers to entry for new seamstresses.[114][115] Prepared skins are available at many northern supply stores today, allowing seamstresses to shop directly for their desired materials.[116] Wringer washing machines may be used to soften hides. Household chemicals like bleach or all-purpose cleaner can produce soft white leather when rubbed on skins.[114][115] Sewing machines and Serger machines make stitching more consistent and less time-consuming.[117] Many women create follow traditional patterns to make traditionally-styled garments from non-traditional materials like cloth, combining old and new techniques.[118][119]

The once-extinct ceremonial clothing of the Copper Inuit has been revived for drum gatherings and other special occasions in Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories.[e][120] The modern Inuit of Igloolik celebrate Qaqqiq, the Return of the Sun, with a fashion show of caribou skin and cloth garments.[121] For many modern practitioners, sewing retains its connection to Inuit spirituality.[122]

Specific programs and initiatives

From 2016 to 2020, the Canadian government allotted $5.7 million through Fisheries and Oceans Canada to support sealing and sealskin crafts in indigenous communities, an effort promoted by Nunavut Member of Parliament Hunter Tootoo, who is known for wearing sealskin accessories like neckties and vests.[123][124] The funding has been used to facilitate sewing workshops such as Nattiq Sealebration, run by the Department of Industry, Tourism and Investment of the Northwest Territories, which teaches professional-level sewing skills and business practices. The workshop program aims to bolster the local market for fur products and support Inuit artisans.[125] In 2017, the Canadian government designated May 20 as National Seal Products Day to support Indigenous sealskin products.[126][94] As of 2023[update], the Northwest Territories government supports programs to assist artisans in acquiring hide and fur materials and accessing international markets.[127]

The northern branch of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, CBC North, increased its coverage of Indigenous sewing in 2022, noting it "plays a vital role in the ongoing cultural revival throughout the North".[128] In April that year, women in Pangnirtung, Nunavut sewed amauti to donate to women fleeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine with their children.[129] In May 2022, Rankin Inlet seamstress Augatnaaq Eccles sewed a parka depicting the colonialist history of tuberculosis sanatoriums in the North.[130] She was invited to bring the parka to Parliament Hill that year for the second annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.[131] Beginning in 2023, a group of Inuit artists and seamstresses called Agguaq began working with museums in order to study ancient garments with an eye to reviving and modernizing the designs.[132]

Contemporary fashion

Modern use of traditional clothing

Many Inuit wear a combination of traditional skin garments, garments which use traditional patterns with imported materials, and mass-produced imported clothing, depending on the season and weather, availability, and the desire to be stylish.[133] The fabric-based atikłuk and the Mother Hubbard parka remain popular and fashionable in Alaska and Northern Canada, respectively.[134] Mothers from all occupations still make use of the amauti, which may be worn over fabric leggings or jeans.[135][136] Both handmade and imported garments may feature logos and images from traditional or contemporary Inuit culture, such as Inuit organizations, sports teams, musical groups, or common northern foodstuffs.[54][137][138]

Store-bought garments are often repurposed or adjusted—seamstresses may add fur ruffs to the hoods of store-bought winter jackets, and boot tops made of skin may be sewn to mass-produced rubber boot bottoms to create a boot that combines the warmth of skin clothing with the waterproofing and grip of artificial materials.[139][140] Traditional patterns may be revised to account for modern needs: amauti are sometimes made with shorter tails for comfort while driving.[54]

Although it is uncommon for modern Inuit to wear complete outfits of traditional skin clothing, fur boots, coats and mittens are still popular in many Arctic places. Skin clothing is preferred for winter wear, especially for Inuit who make their living outdoors in traditional occupations such as hunting and trapping, or modern work like scientific research.[92][104][141][142] Traditional skin clothing is also preferred for special occasions like drum dances, weddings, and holiday festivities.[142][143]

Even garments made from woven or synthetic fabric today adhere to ancient forms and styles in a way that makes them simultaneously traditional and contemporary.[144][145] Modern Inuit clothing has been studied as an example of sustainable fashion and vernacular design.[146][147] Much of the clothing worn today by Inuit dwelling in the Arctic has been described as "a blend of tradition and modernity."[79] Issenman describes the continued use of traditional fur clothing as not simply a matter of practicality, but "a visual symbol of one's origin as a member of a dynamic and prestigious society whose roots extend into antiquity."[79]

Inuit-led fashion and protection of the amauti

Beginning in the 1990s, Pauktuutit (Inuit Women of Canada) began to promote Inuit fashion and culture outside of the Canadian Arctic by collaborating with Canadian museums, exhibitions, and festivals to showcase Inuit-designed garments.[148][149] The response to these events was positive, and in 1998, Pauktuutit launched a program called "The Road to Independence", which aimed to promote Inuit women's economic independence by providing them the skills to design, produce, and sell garments in the contemporary fashion industry.[150] The program was successful, but raised concerns that traditional Inuit clothing pieces, especially the woman's parka or amauti, might be appropriated and genericized by non-Inuit, in the same way that Inuit cultural developments like kayaks, parkas, and to some extent even kamiit have.[148][149]

In 1999, American designer Donna Karan of DKNY sent representatives to the western Arctic to purchase traditional garments, including amauti, to use as inspiration for an upcoming collection.[151][148] Her representatives did not disclose the purpose of their visit to the local Inuit, who only became aware of the nature of the visit after a journalist contacted Inuit women's group Pauktuutit seeking comment. Pauktuutit described the company's actions as exploitative, stating "the fashion house took advantage of some of the less-educated people who did not know their rights."[152] The items they purchased were displayed at the company's New York boutique, which Pauktuutit believed was done without the knowledge or consent of the original seamstresses.[149] After a successful letter-writing campaign organized by Pauktuuit, DKNY cancelled the proposed collection.[151][148]

In 2001, following concerns raised by the Road to Independence project and the subsequent DKNY controversy, Pauktuutit launched the Amauti Project, which aimed to order to explore potential methods for legally protecting the amauti as an example of traditional knowledge collectively owned by all Inuit women.[153] After consultation with numerous Inuit seamstresses, the project released a report which concluded, "All Inuit own the amauti collectively, though individual seamstresses may use particular designs that are passed down between generations."[151][153] To safeguard that collective cultural ownership, Pauktuutit has lobbied the Canadian federal government and the World Intellectual Property Organization to create a special protected status for the amauti, but as of 2020[update], no such protection has been established.[154]

The growth of Inuit fashion is supported by national organizations like Pauktuutit and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, as well as local development associations like the Nunavut Arts and Crafts Association and the Nunavut Development Corporation.[155][156] Contemporary Inuit fashion has been featured in art exhibitions and fashion shows within the Arctic and outside of it.[156][157] In 2016, Quebec art collective Axe Néo-7 held an exhibition of contemporary Inuit art, Floe Edge, which featured modern sealskin fashion by Inuit designers: lingerie by Nala Peter and high heels by Nicole Camphaug.[98][158] In 2017, Martha Kyak was the first Inuit designer to be featured at the Indigenius Art Music and Fashion Show in Ottawa.[159] Inuit designers Victoria Kakuktinniq and Melissa Attagutsiak were invited to show at the Indigenous Fashion Week event at Paris Fashion Week in March 2019.[156][160] In 2020, the Winnipeg Art Gallery launched an exhibition called Inuk Style featuring both historical and contemporary Inuit fashion.[161] Kakuktinniq also presented at New York Fashion Week in February 2020.[162] Kyak presented at Vancouver Fashion Week in 2022.[163]

Materials and visual style

Inuit fashion is a subset of the wider Indigenous American fashion movement. Contemporary Inuit and northern designers use a mix of modern and traditional materials to create garments in both traditional and modern silhouettes. Victoria Kakuktinniq's work, which has been cited as a major influence in the modernization of Inuit fashion, focuses on parkas with traditional styling.[156][164] Melodie Haana-SikSik Lavallée combined satin with sealskin to make items that ranged from "Victorian gowns and bustiers to flapper-inspired dresses and 60s-inspired suits".[165] Many designers also make jewellery from local or sustainable materials such as bone.[156][160]

Some designers center aspects of Inuit culture through the visual design of their products. Artist and designer Becky Qilavvaq has produced garments printed with Inuit song lyrics and images of traditional tools.[166] Similarly, designer Adina Tarralik Duffy has produced onesies and leggings printed with the packaging designs found on common northern food products like McCormicks Pilot Biscuits and Klik canned ham.[167] Martha Kyak's clothing incorporates geometric designs that originated with traditional Inuit tattooing.[168]

Those who focus on traditional materials such as sealskin often do so in support of traditional Inuit culture and the promotion of sustainable fashion.[81][98][169] Designer Rannva Simonsen, a Faroe Islander who emigrated to Nunavut in 1997, has been working with sealskin since 1999.[81][170] Nicole Camphaug originally started by experimenting with sewing sealskin scraps to her own boots, eventually turning to commercial sales of seal-trimmed shoes after friends and family asked for their own.[171] The use of sealskin, a traditional Inuit clothing material, has been controversial among non-Inuit due to the influence of anti-sealing campaigns by animal rights groups such as Greenpeace Canada and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA).[81][92][101] Since the late 2010s, some designers have reported that Canadians outside the Arctic appeared to be increasingly supportive of Inuit sealskin fashion.[81][172]

E-commerce, particularly via social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, has facilitated the popularity and sales of Inuit-designed clothing outside northern communities.[173][174][94] This has sometimes generated controversy: Inuit crafters and clothing designers have had sales listings for seal products blocked on social media sites.[175] Throat singer Tanya Tagaq had her Facebook account suspended in 2017 after posting a photo of a sealskin coat; Facebook apologized and reversed the action within hours.[176]

Appropriation by Southern fashion industry

The intersection between traditional Inuit clothing and the non-Inuit or "Southern" fashion industry has often been contentious. Inuit seamstresses and designers have described instances of non-Inuit designers making use of traditional Inuit design motifs and clothing styles without obtaining permission or giving credit. In some cases, designers have altered original Inuit designs in a way that distorts their cultural context, but continue to label the products in a way that makes them appear to be authentically Inuit.[152][177] Inuit designers have criticized this practice as cultural appropriation.[151][178][179]

The fashion industry has taken inspiration from Inuit clothing since the polar exploration craze of the late 19th to early 20th centuries.[180] The fur coat, in the sense of a full-length coat made with fur covering the exterior, did not appear in European fashion until this time – historically, fur had been used as a trim or a liner, but usually not as the basis for an entire garment. Fashion historian Jonathan Faiers argues that this trend may have been influenced by fur clothing encountered during polar exploration.[181] The parka and the puffer jacket, now mainstays of Southern fashion, both developed from Inuit designs.[182]

A Vogue cover from 1917 depicts a model clad in white fur spearing a polar bear. Her garments, while stylized and unrealistic, appear to take visual influence from the clothing of the Greenlanic Inuit.[181] From approximately 1915 to 1921, curators at the American Museum of Natural History collaborated with fashion designers to create an American clothing style inspired by Indigenous cultures of North and South America, including the Inuit.[183] In the 1920s, American designer Max Meyer drew inspiration from Inuit garments at the Brooklyn Museum.[184] The 1922 film Nanook of the North has been a popular source of inspiration to fashion designers since its release.[185]

Arctic- and Inuit-inspired clothing became trendy again in 1960s fashion, with the increased popularity of sportswear as fashion.[186] Fashion photographs of these looks often included tropes of exoticism, savagery, and barbarianism, perpetuating the dominant Southern view of Indigenous peoples as uncivilized.[186] Snow goggles, an Inuit device for protecting the eyes from snow blindness, were also interpreted by Southern designers during this era. French designer André Courrèges paired white plastic versions with his Space Age fashion.[187] During the 1990s, Inuit-inspired clothing returned to prominence.[188] French designer Jean Paul Gaultier and American designer Isaac Mizrahi both released collections which incorporated Inuit concepts for Fall/Winter 1994, titled Le Grande Voyage and Nanook of the North, respectively.[188] Icelandic artist Björk walked the runway for Voyage in a jacket made of fur and skins.[188] Mizrahi's collection paired parkas and furs with voluminous, brightly-colored evening gowns.[189]

In 2015, London-based design house KTZ released a collection which included a number of Inuit-inspired garments. Of particular note was a sweater with designs taken directly from historical photographs of an Inuit shaman's unique caribou parka.[190] The garment, known variously as the Shaman's Parka or the Inuit Angakkuq Coat, is well-known to scholars of Inuit culture; Bernadette Driscoll Engelstad described it as "the most unique garment known to have been created in the Canadian Arctic."[191][192] It was designed in the late 19th century by the angakkuq Qingailisaq and sewn by his wife, Ataguarjugusiq. Either Qingailisaq or his son, the angakkuq Ava, sold the coat to Captain George Comer in 1902, who brought it to the American Museum of Natural History.[f][5][192] Its intricate designs, which resemble Koryak and Chukchi motifs, were inspired by spiritual visions.[5] Ava's great-grandchildren criticized KTZ for failing to obtain permission to use the design from his family.[190] After the criticism was picked up by the media, KTZ issued an apology and pulled the item from the market.[193] French fashion designer Joseph Altuzarra had also drawn inspiration from the Shaman's Parka in his Fall/Winter 2012 collection, but to a lesser degree that did not result in controversy.[194]

Some brands have made efforts to work with Inuit designers directly. In 2019, Canadian winterwear brand Canada Goose launched Project Atigi, commissioning fourteen Canadian Inuit seamstresses to each design a unique parka or amauti from materials provided by Canada Goose. The designers retained the rights to their designs. The parkas were displayed in New York City and Paris before being sold, and the proceeds, which amounted to approximately $80,000, were donated to national Inuit organization Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK).[155][195] The original Project Atigi was criticized by some Inuit designers for not being sufficiently publicized to potential applicants.[196]

The following year, the company released an expanded collection called Atigi 2.0, which involved eighteen seamstresses who produced a total of ninety parkas. The proceeds from the sales were again donated to ITK. Gavin Thompson, vice-president of corporate citizenship for Canada Goose told CBC that the brand had plans to continue expanding the project in the future.[195] A parka from the original collection was displayed at the Inuk Style exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 2020.[161] In 2022, Kakuktinnniq designed a capsule collection for the third iteration of Project Atigi. The advertising campaign for the collection featured Inuit women as models: throat singer Shina Novalinga, actress Marika Sila and model Willow Allen.[197]

Notes

- ^ Kamiit is the Eastern Arctic term for boots, and mukluk is the Western Arctic equivalent. While there are some stylistic differences between them, they are functionally the same. This article refers to all Inuit boots as kamiit for consistency. The singular form of kamiit is kamik.[3]

- ^ The source uses the Before Present time scale for radiocarbon dating, which considers the present era to begin in 1950.

- ^ The European Economic Community is a predecessor to the European Union. Upon the formation of the EU in 1993, the EEC was incorporated into the EU and renamed the European Community (EC). In 2009, the EC formally ceased to exist and its institutions were directly absorbed by the EU.

- ^ Nunavut was not partitioned out from the Northwest Territories until 1999.

- ^ Ulukhaktok was formerly called Holman.

- ^ Ava is also frequently transliterated as Aua and Awa.

References

- ^ Stenton 1991, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 11.

- ^ Oakes & Riewe 1995, pp. 50, 54, 60.

- ^ a b Graburn 2005, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Issenman 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Stenton 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Issenman 1997b, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Renouf & Bell 2008, p. 36.

- ^ a b Issenman 1997b, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 11.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 9, 18.

- ^ a b Issenman 1997b, p. 44.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 18, 234.

- ^ a b Issenman 2000, p. 112.

- ^ Issenman 1997b, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 21.

- ^ Issenman 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 24.

- ^ Stenton 1991, p. 16.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 98, 172.

- ^ Inuktitut Magazine 2011, p. 14.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 171.

- ^ McGovern 2000, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 173–174.

- ^ McGovern 2000, p. 336.

- ^ a b Issenman 1997a, p. 164.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 174.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 29.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 98.

- ^ a b Hall 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b c Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Trott 2001, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 108, 117, 174.

- ^ Reitan 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Buijs 2005, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Trott 2001, p. 180.

- ^ Schmidt 2018, p. 124.

- ^ Bahnson 2005, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 81, 89–90.

- ^ Buijs 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 175.

- ^ Pharand 2012, p. 64.

- ^ a b Pharand 2012, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Petersen 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 176.

- ^ Pharand 2012, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Issenman 1997a, pp. 108, 117.

- ^ a b Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 100.

- ^ a b Martin 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. 100, 166.

- ^ Hall 2001, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Sponagle, Jane (30 December 2014). "Inuit parkas change with the times". CBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Buijs 2005, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 98.

- ^ a b Dubuc 2002, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f Pickman 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Pickman 2017, p. 32.

- ^ Pickman 2017, p. 37.

- ^ MacDonald 2018, p. 53.

- ^ Hall 2001, p. 133.

- ^ a b Issenman & Rankin 1988, p. 138.

- ^ a b Rholem 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Pickman 2017, p. 41.

- ^ a b Pickman 2017, p. 42.

- ^ Sancton 2021, pp. 37–38, 41.

- ^ Sancton 2021, pp. 42–43, 47.

- ^ Millar 2015, p. 434–435.

- ^ Sancton 2021, pp. 109, 192.

- ^ Pickman 2017, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Pickman 2017, p. 195, Note 81.

- ^ Pickman 2017, pp. 50, 52.

- ^ Pickman 2017, pp. 44, 55.

- ^ Hall 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Oakes & Riewe 1997, p. 93.

- ^ Oakes 1987, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Issenman 1997a, p. 177.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, pp. 3, 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kassam, Ashifa (11 May 2017). "'It's our way of life': Inuit designers are reclaiming the tarnished sealskin trade". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 179.

- ^ a b Issenman 1997a, p. 224.

- ^ McGregor 2011, p. 4.

- ^ Oakes 1987, p. 47.

- ^ Oakes 1987, pp. 46, 49.

- ^ Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Hall 2001, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Petrussen 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Campbell, Heather (5 May 2021). "How Nunatsiavut Artists Use Their Work to Fight Climate Change". Inuit Art Foundation. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Issenman 1997a, p. 242.

- ^ Oakes 1987, p. 48.

- ^ a b c "Inuit designers revive sealskin fashion, celebrate 'National Seal Products Day,' May 20". Indian Country Today. 20 May 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Graugaard 2020, p. 385.

- ^ Copenhagen, Malcolm Brabant in (16 May 2015). "Inuit hunters' plea to the EU: lift ban seal cull or our lifestyle will be doomed". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Graugaard 2020, p. 374.

- ^ a b c McCue, Duncan (14 March 2016). "Putting sexy back in sealskin: Nunavut seamstresses aim for high-end fashion market". CBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Patar, Dustin (27 January 2020). "Inuit exemption to European Union's seal product ban is ineffective: report". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Zerehi, Sima Sahar (30 August 2016). "Crystal Serenity brings sales boom to Nunavut artists? Not so fast". CBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Hwang, Priscilla (5 February 2017). "Why this Inuk son chose to proudly wear a sealskin parka made by his mom, amid social media backlash". CBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Graugaard 2020, p. 378.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, pp. ix–x.

- ^ a b Petrussen 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Graburn 2005, p. 135.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, pp. 163, 167.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 226.

- ^ Tulloch, Kusugak & et al. 2013, pp. 28–32.

- ^ Issenman 1997a, p. 225.

- ^ "Parka class in Whitehorse revives northern style". CBC News. 4 January 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Hwang, Priscila (14 January 2017). "Nunavut's 96-year-old seamstress models her own clothes, advocates for traditional designs". CBC News. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Heidi, Atter (20 August 2023). "Inuit women reviving traditional black-bottom sealskin boots through summer workshops". CBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Emanuelsen 2020, pp. 3, 7.

- ^ a b Oakes 1987, pp. 14, 34.

- ^ a b Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 18.

- ^ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 34, 171.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 108.

- ^ Pharand 2012, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Oakes & Riewe 1997, p. 100.

- ^ Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Pharand 2012, p. 71.

- ^ Emanuelsen 2020, p. 9.

- ^ "Certification and Market Access Program for Seals". Government of Canada. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Zerehi, Sima Sahar (17 May 2016). "Are attitudes around seal products changing?". CBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Morritt-Jacobs, Charlotte (6 March 2020). "Stitching connection and culture through seal skin". APTN News. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Sara, Frizzell (27 May 2017). "Canada will celebrate its first National Seal Products Day this Saturday". CBC News. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Beaulne-Stuebing, Laura (28 January 2023). "How Indigenous people are strengthening fur traditions in an anti-fur world". CBC Radio. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Bear intestines, fish skins and red carpet runways: The year in sewing". CBC News. 30 December 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Hudson, April (25 April 2022). "Elder's dream to sew amautis for Ukrainian mothers 'catches fire' in Pangnirtung". CBC News. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Inuk student sews parka to tell 'heartbreaking' story of tuberculosis sanatoriums". CBC News. 2 May 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Pelletier, Jeff (30 September 2022). "Rankin Inlet student's parka takes centre stage on Parliament Hill". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Palliser, Lyndsay-Ann (9 September 2023). "A group of Inuit artists is travelling to museums to study traditional Inuit clothing and tools". CBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Issenman & Rankin 1988, p. 146.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 101, 108.

- ^ Rholem 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 108–113, 115.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 115.

- ^ Rohner 2017.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, p. 110.

- ^ Hall, Oakes & Webster 1994, pp. 18, 107.

- ^ Oakes 1987, p. 6.

- ^ a b Rholem 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 19, 31.

- ^ Reitan 2007, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Oakes & Riewe 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Skjerven & Reitan 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Reitan 2007, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Bird 2002, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Dewar 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Bird 2002, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Madwar, Samia (June 2014). "Inappropriation". Up Here. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ a b Dewar 2005, p. 24.

- ^ a b Bird 2002, p. 3–4.

- ^ Lakusta, Adam (24 July 2020). "Reforming Canada's Intellectual Property Laws: The Slow Path To Reconciliation". Canadian Bar Association. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ a b McKay, Jackie (4 February 2019). "Canada Goose unveils parkas designed by Inuit designers". CBC News. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Rogers, Sarah (27 March 2019). "Nunavut fashion and design come into their own". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Northern Scene: The dawning of a new era of Inuit artistry". Arctic Journal. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Gessell, Paul (1 February 2016). "Performance art? Inuit art? An embrace of Arctic heritage? – Call it unforgettable". Ottawa Magazine. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Frizzell, Sara (19 April 2017). "Inuit fashion featured for the first time at Indigenius show in Ottawa". CBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ a b Boon, Jacob (April–May 2019). "From Iqaluit to the Eiffel Tower". Up Here. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b Monkman, Lenard (29 October 2020). "Winnipeg Art Gallery exhibition puts spotlight on Inuit clothing and jewelry". CBC News. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ McKay, Jackie (8 January 2020). "Victoria's Arctic Fashion gearing up for New York Fashion Week". CBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Bowen, Dana (September–October 2022). "A New Era of High Fashion". Up Here. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Bowen, Dana (September–October 2022). "A New Era of High Fashion". Up Here. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Zerehi, Sima Sahar (10 July 2015). "Haana-SikSik, Inuk fashion designer, brings her designs home". CBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Kurup, Rohini; Jung, Harry (21 April 2017). "Inuit artist Becky Qilavvaq melds clothing and culture". The Bowdoin Orient. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Rohner, Thomas (9 February 2017). "Winnipeg conference showcases Nunavut designers, businesses". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Allford, Jennifer (23 October 2019). "Reclaiming Inuit culture, one tattoo at a time". CNN. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Sardone, Andrew (17 January 2014). "High fashion's new home in the Canadian North". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Nunavut fur designer moves into downtown Iqaluit shop". CBC News. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Nicole Camphaug takes sealskin footwear to new heights". CBC News. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Brown, Beth (28 February 2018). "This Iqaluit-Based Designer Can Hand-Make a Luxe Parka in 2.5 Hours". Flare. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Emanuelsen 2020, p. 10.

- ^ "11 Inuit designers to see at the Indigenous Fashion Arts Festival". Inuit Art Quarterly. Inuit Art Foundation. 9 June 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Patar, Dustin (30 December 2019). "Inuit crafters continue to be blocked on Facebook for selling sealskin". Nunatsiaq News. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Tanya Tagaq says her Facebook account was temporarily suspended over seal fur photo". CBC News. 2 February 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Dubuc 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Grant, Meghan (25 May 2018). "Inuit 'wear their culture on their sleeve, literally': Inuk designer gears up for Indigenous fashion week". CBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Scott, Mackenzie (29 March 2019). "Debate in Inuvik over who should sell traditional crafts". CBC News. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Mears 2017, p. 61.

- ^ a b Mears 2017, p. 62.

- ^ Mears 2017, p. 84.

- ^ Mears 2017, pp. 62, 64.

- ^ Mears 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Mears 2017, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Mears 2017, p. 67.

- ^ Mears 2017, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Mears 2017, p. 74.

- ^ Mears 2017, p. 77.

- ^ a b "Nunavut family outraged after fashion label copies sacred Inuit design". CBC Radio. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Zerehi, Sima Sahar (2 December 2015b). "Inuit shaman parka 'copied' by KTZ design well-studied by anthropologists". CBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ a b MacDuffee, Allison (31 August 2018). "The Shaman's Legacy: The Inuit Angakuq Coat from Igloolik". National Gallery of Canada. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "U.K. fashion house pulls copied Inuit design, here's their apology". CBC Radio. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Mears 2017, p. 100.

- ^ a b McKay, Jackie (19 January 2020). "Inuit designers launch new line of parkas for Canada Goose". CBC News. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Inuk designer says not everyone informed about Canada Goose program -US". APTN National News. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Cardin-Goyer, Camille (February 2022). "Reclaiming Their Culture". Elle Canada. p. 70.

Bibliography

Books

- Buijs, Cunera; Oosten, Jarich, eds. (1997). Braving the Cold: Continuity and Change in Arctic Clothing. Leiden, The Netherlands: Research School CNWS, School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies. ISBN 90-73782-72-4. OCLC 36943719.

- Issenman, Betty Kobayashi. "Stitches in Time: Prehistoric Inuit Skin Clothing and Related Tools". Braving the Cold: Continuity and Change in Arctic Clothing. pp. 34–59.

- Oakes, Jill; Riewe, Rick. "Factors Influencing Decisions Made by Inuit Seamstresses in the Circumpolar Region". Braving the Cold: Continuity and Change in Arctic Clothing. pp. 89–104.

- Hall, Judy (2001). ""Following The Traditions of Our Ancestors": Inuit Clothing Designs". In Thompson, Judy (ed.). Fascinating Challenges: Studying Material Culture with Dorothy Burnham. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv170p6. ISBN 9781772823004. JSTOR j.ctv170p6.

- Hall, Judy; Oakes, Jill E.; Webster, Sally Qimmiu'naaq (1994). Sanatujut: Pride in Women's Work. Copper and Caribou Inuit Clothing Traditions. Hull, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization. ISBN 0-660-14027-6. OCLC 31519648.

- Issenman, Betty Kobayashi; Rankin, Catherine (1988). Ivalu: Traditions Of Inuit Clothing. Montréal: McCord Museum of Canadian History. ISBN 0-7717-0182-9. OCLC 17871781.

- Issenman, Betty Kobayashi (1997). Sinews of Survival: the Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-5641-6. OCLC 923445644.

- Issenman, Betty Kobayashi (2000). "Many Disciplines, Many Rewards: Inuit Clothing Research". In Eicher, Joanne Bubolz; Evenson, Sandra Lee; Lutz, Hazel A. (eds.). The Visible Self: Global Perspectives on Dress, Culture, and Society. New York : Fairchild Publications. pp. 110–117. ISBN 978-1-56367-068-8 – via Internet Archive.

- King, J.C.H.; Pauksztat, Birgit; Storrie, Robert, eds. (2005). Arctic Clothing. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-3008-9.

- Bahnson, Anne. "Women's Skin Coats from West Greenland – with Special Focus on Formal Clothing of Caribou Skin from the Early Nineteenth Century". Arctic Clothing. pp. 84–90.

- Buijs, Cunera. "Clothing as a Visual Representation of Identities in East Greenland". Arctic Clothing. pp. 108–114.

- Dewar, Veronica (2005). "Keynote Address: Our Clothing, Our Culture, Our Identity". Arctic Clothing. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 23–26. ISBN 9780773530089.

- Graburn, Nelson (2005). "Clothing in Inuit Art". Arctic Clothing. pp. 132–138.

- Martin, Cyd. "Caribou, Reindeer and Rickrack: Some Factors Influencing Cultural Change in Northern Alaska, 1880–1940". Arctic Clothing. pp. 121–126.

- Petrussen, Frederikke. "Arctic Clothing from Greenland". Arctic Clothing. pp. 45–47.

- McGovern, Thomas H. (2000). "The Demise of Norse Greenland". In Fitzhugh, William W.; Ward, Elisabeth I. (eds.). Vikings: the North Atlantic Saga. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-970-7 – via Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, John; Wachowich, Nancy, eds. (2018). The Hands' Measure: Essays Honouring Leah Aksaajuq Otak's Contribution to Arctic Science. Iqaluit, Nunavut: Nunavut Arctic College Media. ISBN 978-1-897568-41-5. OCLC 1080218222.

- MacDonald, John. "Stories and Representation: Two Centuries of Narrating Amitturmiut History". In MacDonald & Wachowich (2018), pp. 43–80.

- McGregor, Heather E. (January 2011). Inuit Education and Schools in the Eastern Arctic. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-5949-3.

- Mears, Patricia, ed. (2017). Expedition: Fashion From the Extreme. Fashion Institute of Technology. New York City: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51997-4. OCLC 975365990.

- Mears, Patricia (2017). "Fashion From the Extreme: The Poles, Highest Peaks, and Beyond". In Mears, Patricia (ed.). Expedition: Fashion From the Extreme. Fashion Institute of Technology. New York City: Thames & Hudson. pp. 56–105. ISBN 978-0-500-51997-4. OCLC 975365990.

- Pickman, Sarah (2017). "Dress, Image, and Cultural Encounter in the Heroic Age of Polar Expedition". In Mears, Patricia (ed.). Expedition: Fashion From the Extreme. Fashion Institute of Technology. New York City: Thames & Hudson. pp. 31–55. ISBN 978-0-500-51997-4. OCLC 975365990.

- Oakes, Jill E. (1987). Factors Influencing Kamik Production in Arctic Bay, Northwest Territories. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Oakes, Jill E.; Riewe, Roderick R. (1995). Our Boots: An Inuit Women's Art. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-55054-195-1. OCLC 34322668.

- Petersen, Robert (2003). Settlements, Kinship and Hunting Grounds in Traditional Greenland. Copenhagen: Danish Polar Center. ISBN 978-87-635-1261-9.

- Pharand, Sylvie (2012). Caribou Skin Clothing of the Igloolik Inuit. Iqaluit, Nunavut: Inhabit Media. ISBN 978-1-927095-17-1. OCLC 810526697.

- Reitan, Janne Beate (2007). Improvisation in Tradition: a Study of Contemporary Vernacular Clothing Design Practiced by Iñupiaq Women of Kaktovik, North Alaska. Oslo: Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 978-82-547-0206-2. OCLC 191444826.

- Rholem, Karim (2001). Uvattinnit: The People of the Far North. Montréal: Stanké. ISBN 2-7604-0794-2. OCLC 46617134.

- Sancton, Julian (2021). Madhouse at the End of the Earth: The Belgica's Journey into the Dark Antarctic Night. Crown. ISBN 978-1-9848-2434-9.

- Skjerven, Astrid; Reitan, Janne Beate (26 June 2017). Design for a Sustainable Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Education. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-85797-0.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Canada's Residential Schools: The Inuit and Northern Experience (PDF). The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Vol. 2. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-9829-4. OCLC 933795281.

Periodicals

- Bird, Phillip (July 2002). Intellectual Property Rights and the Inuit Amauti: A Case Study (PDF) (Report). Pauktuutit Inuit Women's Association.

- Driscoll-Engelstad, Bernadette (2005). "Dance of the Loon: Symbolism and Continuity in Copper Inuit Ceremonial Clothing". Arctic Anthropology. 42 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0010. ISSN 0066-6939. JSTOR 40316636. S2CID 162200500.

- Dubuc, Élise (Fall 2002). "Culture matérielle et représentations symboliques par grands froids: les vêtements de Pindustrie du plein air et la tradition inuit". Material Culture Review (in French). 56.

- Emanuelsen, Kristin (2020). The Importance of Sewing: Perspectives from Inuit Women in Ulukhaktok, NT (Report). Ulukhaktok Community Corporation, Indigenous Services Canada, and University of the Sunshine Coast.

- Graugaard, Naja Dyrendom (2020). "'A Sense of Seal' in Greenland: Kalaallit Seal Pluralities and Anti-Sealing Contentions". Études/Inuit/Studies. 44 (1/2): 373–398. doi:10.2307/27078837. ISSN 0701-1008.

- "Through the Lens: Kamiit" (PDF). Inuktitut Magazine. No. 110. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. 1 May 2011. pp. 14–21.

- Millar, Pat (July 2015). "Frederick A. Cook: the role of photography in the making of his polar explorer-hero image". Polar Record. 51 (4): 432–443. doi:10.1017/S0032247414000424. ISSN 0032-2474. S2CID 145383153.

- Renouf, M. A. P.; Bell, T. (2008). "Dorset Palaeoeskimo Skin Processing at Phillip's Garden, Port au Choix, Northwestern Newfoundland". Arctic. 61 (1): 35–47. doi:10.14430/arctic5. ISSN 0004-0843. JSTOR 40513180.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth (2018). "The Holmberg Collection of Skin Clothing from Kodiak Island at the National Museum of Denmark". Études/Inuit/Studies. 42 (1): 117–136. doi:10.7202/1064498ar. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26775763. S2CID 204265611.

- Stenton, Douglas R. (1991). "The Adaptive Significance of Caribou Winter Clothing for Arctic Hunter-gatherers". Études/Inuit/Studies. 15 (1): 3–28. JSTOR 42869709.

- Trott, Christopher G. (June 2001). "The Dialectics of "Us" and "Other": Anglican Missionary Photographs of the Inuit". American Review of Canadian Studies. 31 (1–2): 171–190. doi:10.1080/02722010109481589. ISSN 0272-2011. S2CID 144005340.

- Tulloch, Shelley; Kusugak, Adriana; et al. (December 2013). "Stitching together literacy, culture & well-being: The potential of non-formal learning programs" (PDF). Northern Public Affairs. 2 (2): 28–32.