Health in Pakistan

Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world with population approaching 225 million.[1] It is a developing country struggling in many domains due to which the health system has suffered a lot. As a result of that, Pakistan is ranked 122nd out of 190 countries in the World Health Organization performance report.[2]

Life expectancy in Pakistan increased from 61.1 years in 1990 to 65.9 in 2019.[3] Pakistan ranked 154th among 195 countries in terms of Healthcare Access and Quality index, according to a Lancet study.[3] Although Pakistan has seen improvement in healthcare access and quality since 1990, with its HAQ index increasing from 26.8 in 1990 to 37.6 in 2016.[4] It still stands at 164th out of 188 countries in terms of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and chance to achieve them by 2030.[3]

According to latest statistics, Pakistan spends 2.95% of its GDP on health (2020).[5] Pakistan per capita income (PPP current international $,) is 6.437.2 in 2022[6] and the current health expenditure per capita (current US$) is 38.18.[7] The total adult literacy rate in Pakistan is 58% (2019)[7] and primary school enrollment is 68%(2018).[7] The gender inequality in Pakistan was 0.534 in 2021 and ranks the country 135 out of 170 countries in 2021.[8] The proportion of population which has access to improved drinking water and sanitation is 91% (2015) and 64% (15) respectively.[9]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[10] finds that Pakistan is fulfilling 69.2% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income.[11] When looking at the right to health with respect to children, Pakistan achieves 82.9% of what is expected based on its current income.[11] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves 90.4% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income.[11] Pakistan falls into the "very bad" category when evaluating the right to reproductive health because the nation is fulfilling only 34.4% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available.[11]

Health infrastructure

Pakistan has a mixed health system, which includes government infrastructure, para-statal health system, private sector, civil society and philanthropic contributors.[12] Alternative and traditional system of healing is also quite popular in Pakistan.

The country undertook a major constitutional reform in 2011 with the 18th amendment, which resulted in abolishment of Ministry of Health and subsequent devolution of powers.As a result, more powers were given to provinces regarding health infrastructure and finances.[13] In keeping with the increased awareness regarding health services Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination was formed in 2011. The main purpose of establishing this body was to provide a health system that gives access to efficient, equitable, accessible & affordable health services. And also, national and international coordination in the field of public health along with population welfare coordination. It also enforced drug laws and regulations.[14] The health care delivery system includes both state and non-state; and profit and not for profit service provision. The country's health sector is marked by urban-rural disparities in healthcare delivery and an imbalance in the health workforce, with insufficient health managers, nurses, paramedics and skilled birth attendants in the peripheral areas.[15] Health care challenges in Pakistan also include issues such as inadequate budgetary allocation, shortage of medical professionals, substandard physical infrastructure, rapid population growth, counterfeit and expensive medicines, shortage of paramedical personnel and presence of unlicensed practitioners.[16]

Sources of health expenditure in Pakistan was mostly "out-of-pocket" spending around 66% followed by the Government health spending at 22.1% in 2005.The situation has improved slightly now with out-of-pocket spending estimated to be 54.3% in 2020 followed by Government health spending of 35.6%.[5]

Primary Health Care

Primary Healthcare system is the very basic health system for providing accessible, good-quality, responsive, equitable and integrated care. Primary healthcare in Pakistan mainly consists of basic health units, dispensaries, Maternal & child health centers (MNCH) and some private clinics at community level. In Sindh (Province in Pakistan), Primary healthcare activities are supported by government itself but managed by external private & non-government organizations like People's primary healthcare initiative (PPHI Sindh), Shifa foundation, HANDS etc.A major strength of government's health care system in Pakistan is an outreach primary health care, delivered at the community level by 100,000 Lady Health Workers (LHWs) and an increasing number of community midwives (CMWs), among other community based workers.[17]

Secondary Health Care

It mainly includes tehsil & district hospitals or some private hospitals. Tehsil & district hospitals (THQs & DHQs) are run by the government, the treatment under government hospitals is free of cost.

Tertiary Health Care

It include both private and government hospitals, well equipped to perform minor and major surgeries. There are usually two or more in every city. Most of the Class “A” military hospitals come in this category. Healthcare and stay comes free of charge in government hospitals. There is also a 24 hours emergency care that usually caters to more than 350 patients every day.[18]

The government of Pakistan has also started “Sehat Sahulat Program”, whose vision is to work towards social welfare reforms, guaranteeing that the lower class within the country gets access to basic medical care without financial risks.[19] Apart from that there are also maternal and child health centres run by lady health workers that aim towards family planning and reproductive health.[20]

Health status

Communicable diseases

Communicable diseases have always been the prime cause of mortalities in Pakistan. The reason for the rapid spread of these diseases include overcrowded cities, unsafe drinking water, inadequate sanitation, poor socioeconomic conditions, low health awareness and inadequate vaccination coverage.

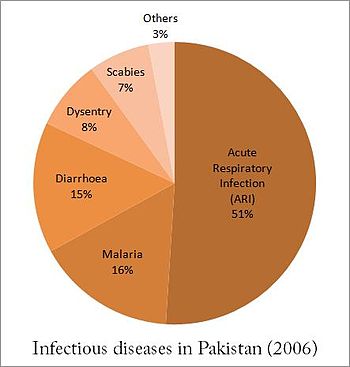

- Acute respiratory infection (51%): Among the victims of ARI, most vulnerable are children whose immune systems have been weakened by malnutrition. In 1990, National ARI Control Programme was started in order to reduce the mortality concerned with pneumonia and other respiratory diseases. In following three years, death rates among victims under age of five in Islamabad had been reduced to half.[21] In 2006, there were 16,056,000 reported cases of ARI, out of which 25.6% were children under age of five.

- Viral hepatitis (7.5%): Viral Hepatitis, particularly that caused by types B and C are major epidemics in Pakistan.[22] Pakistan remains in the intermediate prevalence area for Hepatitis B with an estimated prevalence rate of 2.5%.[23] The main cause remains massive overuse of therapeutic injections and re-use of syringes during these injections in the private sector healthcare.

- Tuberculosis: According to National Institute of Health presently the prevalence of TB in Pakistan is 348 per 100,000.Whereas, number of new cases are reportedly 276 per 100,000 population. National TB Control Program (NTP) was renewed by Ministry of Health subsequent to declare TB as a national emergency in Pakistan in 2001 and is currently working along with National Institute of Health, Pakistan.[24] The country is said to have the fourth highest prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) globally. Factors causing this are delayed diagnosis, unsupervised, improper drug regimens, lack of follow-up and little or no social support programme.[25]

- Malaria (16%): It is a problem faced by the lower-class people in Pakistan. The unsanitary conditions and stagnant water bodies in the rural areas and city slums provide excellent breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Use of nets and mosquito repellents is becoming more common. In Pakistan, malarial incidence reaches its peak in September. 1000 million people have died from Malaria since Pakistan came into being till December 2012.[26] In 2006, there were around 4,390,000 new reported cases of fever.Pakistan was slowly but steadily working towards control of malaria cases till the floods of 2022.According to Global Fund estimates,Pakistan saw at least a four-fold increase in the reported malaria cases after the floods, from 400,000 cases in 2021 to more than 1.6 million cases in 2022 in the 60 districts.[27] Baluchistan and Sindh were the most affected provinces.

Infectious diseases in Pakistan by proportion (2006) - Diarrhea (15%): There were around 4,500,000 reported cases in 2006, 14% of which were children under the age of five.

- Dysentery (8%) and Scabies (7%)

- Coronavirus: As per statistics published by world o meter, almost 326,431 cases were reported till November, 2020.[28] Out of these cases, there were 7,000 casualties and most of them were older people. However, Pakistan managed to avoid too much cases by taking COVID-19 precautionary measures at the early stage.

Noncommunicable diseases

Mental health disorders and injuries cause morbidity and mortality in Pakistan.[29] They account for 58% of all deaths in the country.[30] Pakistan has the sixth highest number of people in the world with diabetes; every fourth adult is overweight or obese; cigarettes are cheap; antismoking and road safety laws are poorly enforced.[29] Pakistan has a high prevalence of blindness, with nearly 1% by WHO criteria for visual impairment – mainly due to cataract. Disability from blindness profoundly affects poverty, education and overall quality of life.[31]

Controllable diseases

- Cholera: As of 2006, there were a total of 4,610 cases of suspected cholera. However, the floods of 2010 suggested that cholera transmission may be more prevalent than previously understood. Furthermore, research from the Aga Khan University suggests that cholera may account for a quarter of all childhood diarrhea in some parts of rural Sindh.

- Dengue fever: The first case of Dengue fever was reported in the country in 1994 but it was not until 2005 that outbreak patterns started appearing.Since the,dengue has become endemic in the country.[32] An outbreak of dengue fever occurred in October 2006 in Pakistan. Several deaths occurred due to misdiagnosis, late treatment and lack of awareness in the local population. But overall, steps were taken to kill vectors for the fever and the disease was controlled later, with minimal casualties.During the dengue epidemic of 2011, Dengue Expert Advisory Group (DEAG) was formed in province of Punjab aiming to control dengue in the province.[33] Along with several campaigns like "Dengue Mukao" (End Dengue) were initiated for public awareness in the province in local languages.[34] According to the National Institute of Health (NIH) Islamabad, 22,938 dengue fever cases were reported in Pakistan in 2017, and about 3,442 cases in 2020. A total of 48,906 cases including 183 deaths were reported in the country from 1 January to 25 November 2021.[35] Several factors like irrational urbanization, climate changes, insufficient waste management system, lack of awareness and effective vaccine, all play role in making Pakistan vulnerable to dengue outbreaks.[32]

- Measles: Pakistan reported about 28,573 cases of measles in 1980 which decreased down to about 2,064 in 2000.After 2010 flooding in Pakistan, there was an approximate twofold increase in reported Measles cases from 4,321 in 2010 to 8,749 in 2013.There was total of 8,378 cases of measles reported in 2022.[36] Currently Pakistan is on number 3 among top 10 countries with measles outbreak in the world.[37] Missed immunization along with malnutrition particularly Vitamin A deficiency contribute towards morbidity and mortality of measles in Pakistan.[38]

- Meningococcal meningitis: As of 2006, there were a total of 724 suspected cases of Meningococcal meningitis.

Poliomyelitis

Pakistan is one of the two countries in which poliomyelitis has not been eradicated. As of 2023,Pakistan and Afghanistan are the only two countries remaining in the world where wild poliovirus type 1 remains endemic.[39] There were a total of 89 reported cases of polio in 2008[40] which decreased to 9 in 2018.[41] There has been total of two cases reported in 2023 so far.Both of these cases were reported in Bannu District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK).[42]

Pakistan Polio Eradication Initiative (PEI) National Emergency Action Plan (NEAP) 2021-2023 was launched in 2021 in line with GPEI Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026.It goal is to permanently interrupt all poliovirus transmission in Pakistan by the end of 2023.[43]

World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said “Pakistan also needs to stop transmission of the virus from Afghanistan. Our New Year’s wish is ‘zero’ polio by end of 2019. The children of Pakistan and the children of the world deserve nothing less. Failure to eradicate polio would result in global resurgence of the disease, with as many as 200,000 new cases every year, all over the world.”

HIV/AIDS

HIV infections have been on the rise since 1987.[44] The former National AIDS Control Programme (it was developed with the Health Ministry) and the UNAIDS states that there are an estimated 97,000 HIV positive individuals in Pakistan. However, these figures are based on dated opinions and inaccurate assumptions; and are inconsistent with available national surveillance data which suggest that the overall number may closer to 40,000.[45][46] From 25 April through 28 June 2019, 30,192 people were screened for HIV, of which 876 were positive.[47]

Cancer

According to latest studies, following five cancers are most prevalent in Pakistan: breast cancer (24.1%), oral cavity (9.6%), colorectum (4.9%), esophagus (4.2%), and liver cancer (3.9%).Most deaths were reported due to breast cancer in Pakistan.[48] Pakistan has the highest rate of Breast Cancer among all Asian countries as approximately 90000 new cases are diagnosed every year out of which 40000 die.[49] Young women usually present at advanced stage of breast cancer, which has negative effect on prognosis.[50] Oral cavity and gastrointestinal cancers continue to be extremely common in both genders. Lung and prostate cancer are comparatively less common. Ovarian cancer also has high prevalence.[51]

Skin Diseases

Eczema is the most common skin disease in Pakistan, followed by dermatological infections including bacterial, viral, fungal, sexually transmitted infections, drug reactions, urticarial and psoriasis.[52]

Family planning

"The government of Pakistan wants to stabilize the population (achieve zero growth rate) by 2020. And maximizing the usage of family planning methods is one of the pillars of the population program".[53] The latest Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) conducted by Macro International with partnership of National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) registered family planning usage in Pakistan to be 30 percent. While this shows an overall increase from 12 percent in 1990-91 (PDHS 1990–91), 8% of these are users of traditional methods.[54]

Approximately 7 million women use any form of family planning and the number of urban family planning users have remained nearly static between 1990 and 2007. Since many contraception users are sterilized (38%), the actual number of women accessing any family planning services in a given year are closer to 3 million with over half buying either condoms or pills from stores directly. Government programs by either the Health or Population ministries together combine to reach less than 1 million users annually.[54] Demographic transition of Pakistan has been delayed by slow onset of fertility decline, with a total fertility rate of 3.8 children per woman - 31 per cent higher than the desired rate.[55]

Some of the main factors that account for this lack of progress with Family Planning include inadequate programs that do not meet the needs of women who desire family planning. Also, there is a lack of health workers who can educate about potential side effects, ineffective campaign to convince women and their families about the value of smaller families. Along with that, the overall social norms of society where women seldom control decisions about their own fertility also play a major role. The single most important factor that has confounded efforts to promote family planning in Pakistan is the lack of consistent supply of commodities and services.[56]

The unmet need for contraception has remained high at around 25% of all married women of reproductive age (higher than the proportion that are using a modern contraceptive and twice as high as the number of women being served with family planning services in any given year[57]) and historically any attempt to supply commodities has been met with extremely rapid rise (over 10% per annum) in contraception users compared with the 0.5% increase in national CPR over the past 50 years.

Currently the government contributes about a third of all FP services and the private sector including NGOs the rest. Within the private sector, franchised clinics offer higher quality health care than unfranchised clinics but there is no discernible difference between costs per client and proportion of poorest clients across franchised and unfranchised private clinics.[58] Government programs are run by both the Ministries of Population Welfare and Health. The most common method used is condoms 33.6%, female sterilization which accounts for 33.2%, injectables 10.7%, IUD 8.8%, Pill 6.1%, lactation ammenorhea method 5.7%, others 1.9%.[59]

| METHODS | USAGE |

|---|---|

| Condoms | 33.6% |

| Female sterilization | 33.2% |

| Injectables | 10.7% |

| IUD | 8.8% |

| Pill | 6.1% |

| Lactation ammenorhea | 5.7% |

| Others | 1.9% |

Maternal Health

The health system in Pakistan is influenced by several factors; communicable, non-communicable diseases, malnutrition in children and women and maternal and child morbidities and mortalities.

Maternal mortality ratio in Pakistan is high at 154 per 100,000 live births (2020).[60] It was 387 in 2000 which decreased to 187 per 100,000 live births in 2015. There is very huge difference in maternal mortality ratio across the country; it is104 in Azad Jammu & Kashmir, and 157 in Gilgit Baltistan. It is almost twice as high in Balochistan (298) as in Punjab (157). It is 26% higher in rural areas than in urban areas.[61]

Percentage of births attended by skilled health personnel also shows trend of increase from 23% in 2001–2002 to 73.7% in 2019.[62] During COVID-19 pandemic, it dropped to 68% in 2019–2020.[62]

According to Demographic Health Survey Pakistan 2019, 41% of maternal deaths in Pakistan are due to obstetric hemorrhage and 29% due to hypertensive disorders.[61]

Child Health

Child mortality rate (Under 5 Mortality Rate) was estimated to be 376.9 in 1950 which decreased to 108 per 1000 live births in 2000.Currently, U5MR of Pakistan is 63.33 per 1000 live births.[63] Similarly, neonatal mortality rate of Pakistan was 103 in 1952 which decreased to 39 per 1000 live births in 2021.[64] Both these rates are still very high when compared to Sustainable Development Goal target 3.1 of 25 for U5MR and 12 for neonatal mortality per 1000 live births.[65] Neonatal disorders, lower respiratory infections, diarrhea, congenital birth defects and malaria caused the most deaths in children under five years of age.[66]

Nutrition

Undernutrition

Nutritionally deprived children not only face difficulties in learning, but also are at prime risk of getting infections, face difficulty in combating and recovering from diseases. According to National Nutrition Survey 2018, around 40.2% children in Pakistan are stunted.[67] There are many reasons behind that but the most important reason and one of the most contributing factors is breastfeeding (early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding & continuation of breastfeeding till 2 years of age). Only 45.8% mothers started breastfeeding to their children on the first day of birth & only 48.4% mothers continued breastfeeding for exclusively 6 months (Exclusive breastfeeding).[67] 17.7% children in Pakistan are wasted[67] which is the very critical as per the standards of World Health Organization (WHO). Despite there are many programs working to decrease the rate of stunting and wasting in Pakistan since the last fluids (2010-2011) but there is no significant improvement in the health of the children. The prevalence of stunting was 43.7% in 2011 & it is 40.2% in 2018, which is still a critical level and the prevalence of wasting was 15.1% in 2011 and it became 17.7% in 2018,[68][67] which shows the failure of all the projects working to combat undernutrition from Pakistan.

Over-nutrition (Overweight/Obesity)

Obesity is a health issue that has attracted concern only in the past few years. Urbanisation and an unhealthy, energy-dense diet (the high presence of oil and fats in Pakistani cooking), as well as changing lifestyles, are among the root causes contributing to obesity in the country. According to a list of the world's "fattest countries" published on Forbes, Pakistan is ranked 165 (out of 194 countries) in terms of its overweight population, with 22.2% of individuals over the age of 15 crossing the threshold of obesity.[69] This ratio roughly corresponds with other studies, which state one-in-four Pakistani adults as being overweight.[70][71]

Research indicates that people living in large cities in Pakistan are more exposed to the risks of obesity as compared to those in the rural countryside. Women also naturally have higher rates of obesity as compared to men. Pakistan also has the highest percentage of people with diabetes in South Asia.[72]

According to one study, "fat" is more dangerous for South Asians than for Caucasians because the fat tends to cling to organs like the liver instead of the skin.[73]

According to National Nutrition Survey Pakistan (NNS 2018), The study estimated the proportion of overweight children under five to be 9.5%, twice the target set by the World Health Assembly.[67]

Malnutrition in Adolescents (10-19 years)

Nutrition status among Adolescents (10–19 years of age) varies differently between boys & girls. In 2018, 21.1% boys and 11.8% girls are underweight, 10.2& boys & 11.4% girls are overweight & 7.7% boys and 5.5% girls are obese. More than half (56.6%) of adolescent girls in Pakistan are anaemic, however only 0.9% have severe anaemia.[67]

Malnutrition in Women of Reproductive age (WRA)

In Pakistan, WRA aged 15–49 years bear a double burden of malnutrition. One in seven (14.4%) are undernourished, a decline from 18% in 2011 to 14%, while overweight and obesity are increasing. In NNS 2011 28% were reported to be overweight or obese, rising to 37.8% 2018. About 41.7% of WRA are anaemic, about 79.7% WRA are vitamin D deficient, over a quarter of WRA (27.3%) are deficient in vitamin A, 18.2% of WRA are iron deficient, About 26.5% of WRA are hypocalcaemic while 0.4% are hypercalcaemic & 22.1% of WRA are zinc deficient.[67]

Micronutrient Deficiencies in children under 5 years of age

More than half (53.7%) of Pakistani children are anaemic and 5.7% are severely anaemic. It was 50.9% in 2001, 61.9% in 2011 and 53.7% in 2018. The prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia is 28.6%, zinc deficiency is 18.6%, vitamin A deficiency is 51.5%, vitamin D deficiency is 62.7%.

Vaccination

.jpg/440px-Checking_for_Immunization_-_Pakistan_(16437841693).jpg)

Some vaccines are mandatory for the residents of Pakistan including Polio, BCG for childhood TB, Pentavalent vaccine (DTP+Hep B + Hib) for Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis, Hepatitis B, Hib pneumonia and meningitis, Measles vaccine and rotavirus vaccine.[74]

Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI)

Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) was launched in Pakistan in 1978.In the beginning, this program was specifically started for childhood tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and measles.With the passage of time several new vaccines were added.[74]

Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPD) included in EPI

Currently 12 diseases are covered in EPI program including childhood tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, diarrhea, pneumonia, hepatitis B, meningitis, typhoid, and rubella.[75]

Progress of EPI in Pakistan

There has been increase in vaccine coverage with BCG vaccine coverage increasing from 62% in 1997 to 95% in 2022.Similarly coverage for DTP1 increased from 69% in 2000 to 93% in 2022.The same trend was also observed for DTP3 with an increase of about 20% but still it stands low at 85% coverage (2022) in comparison. This means that about 8% of children who are vaccinated for DTP1 do not get vaccinated for DTP3. Similar trends have also been observed for other vaccines.[76]

| Disease | Causative agent | Vaccine | Doses | Age of administration |

| Childhood TB | Bacteria | BCG | 1 | Soon after birth |

| Poliomyelitis | Virus | OPV | 4 | OPV0: soon after birth

OPV1: 6 weeks OPV2: 10 weeks OPV3: 14 weeks |

| IPV | 1 | IPV-I: 14 weeks | ||

| Diphtheria | Bacteria | Pentavalent vaccine

(DTP+Hep B + Hib) |

3 | Penta1: 6 weeks

Penta2: 10 weeks Penta3: 14 weeks |

| Tetanus | Bacteria | |||

| Pertussis | Bacteria | |||

| Hepatitis B | Virus | |||

| Hib pneumonia and meningitis | Bacteria | |||

| Measles | Virus | Measles | 2 | Measles1: 9 months

Measles2: 15months |

| Diarrhoea due to rotavirus | Virus | *Rotavirus | 2 | Rota 1: 6 weeks

Rota 2: 10 weeks |

Climate change implications on health

Pakistan is one of the five most affected countries in the world due to climate change from the year 1999–2018.[77] Pakistan's vulnerability to climate change is a result of its geographic location, heavy reliance on agriculture and water resources, limited adaptive capacity among its people, and an inadequate emergency preparedness system.Climate-related hazards in Pakistan include floods, which bring risks of diseases like Diarrhea, Gastroenteritis, Skin Infections, Eye Infections, Acute Respiratory Infections, and Malaria. Droughts increase health risks such as food insecurity, malnutrition, Anaemia, Night blindness, and Scurvy. Rising temperatures pose threats like Heat Stroke, Malaria, Dengue, Respiratory Diseases, and Cardiovascular diseases.[78]

In 2015, Karachi and surrounding areas of Sindh province, faced a heatwave that led to over 65,000 hospitalizations [79] and over 2000 deaths.[80]

The worst example of climate change impact on health in Pakistan was 2022 flooding which submerged about one third of the country, affecting 33 million people, half of whom were children. The floods damaged most of the water systems in affected areas, forcing more than 5.4 million people to rely solely on contaminated water from ponds and wells.[81] This crisis highlighted a significant lack of emergency preparedness. The economic and health toll was immense, with 1,730 deaths resulting from the 2022 floods, displacing 8 million individuals and exposing them to disease and under-nutrition. Notably, 89,000 people in Sindh and 116,000 in Baluchistan remain permanently displaced.[82]

Post-disaster assessments predict that these floods will push an additional 8.4–9.1 million people below the poverty line, reversing health gains.[83] Over 2.5 million people lack access to safe drinking water, and Malaria outbreaks have been reported in at least 12 districts of Sindh and Balochistan. The situation is dire, with over 7 million children and women urgently requiring access to nutrition services.[84]

Pakistan EPA (Environment Protection Agency) has been formed with the aim to combat changing climate and its implications on Pakistani population.It is an executive agency of the Government of Pakistan managed by Ministry of Climate Change.[85]

It was reported in August 2023 that approximately 100,000 people have been evacuated from flooded villages in Punjab, with over 175 rain-related deaths in whole of Pakistan during this monsoon season, primarily due to electrocution and building collapses. These events underscore the pressing need for comprehensive climate resilience and emergency response strategies in Pakistan.[86]

References

- ^ Wang, Haidong; Abbas, Kaja M; Abbasifard, Mitra; Abbasi-Kangevari, Mohsen; Abbastabar, Hedayat; Abd-Allah, Foad; Abdelalim, Ahmed; Abolhassani, Hassan; Abreu, Lucas Guimarães; Abrigo, Michael R M; Abushouk, Abdelrahman I; Adabi, Maryam; Adair, Tim; Adebayo, Oladimeji M; Adedeji, Isaac Akinkunmi (October 2020). "Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019". The Lancet. 396 (10258): 1160–1203. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30977-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7566045. PMID 33069325.

- ^ "World Health Organization Report" (PDF). Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Lancet: Pakistan faces double burden of communicable, non-communicable diseases, and persistent inequities | The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation". www.healthdata.org. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan ranks 154 among 195 countries in healthcare". The Frontier Post. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Global Health Expenditure database". WHO - Global Health Expenditure Database.

- ^ "GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) - Pakistan | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Nations, United. Specific country data (Report). United Nations.

- ^ "Gapminder Tools". www.gapminder.org. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Pakistan - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Sahoo, Pragyan Monalisa; Rout, Himanshu Sekhar (1 August 2023). "Analysis of public health-care facilities in rural India". Facilities. 41 (13/14): 910–926. doi:10.1108/f-07-2022-0098. ISSN 0263-2772. S2CID 260414559.

- ^ "Final Report of Implementation Commission.pdf" (PDF). ipc.gov.pk.

- ^ "Ministry of National Health Services Regulation and Coordination". www.nhsrc.gov.pk/.

- ^ "www.who.int" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2007.

- ^ Newspaper, the (1 March 2012). "Poor health facilities". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Jooma, Rashid (1 April 2014). "Political Determinants of Health: Lessons for Pakistan". Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 30 (3): 457–461. doi:10.12669/pjms.303.5487. ISSN 1681-715X. PMC 4048485. PMID 24948958.

- ^ "Health System Profile - Pakistan". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- ^ "About The Program". Sehat Sahulat Program.

- ^ Siddiqi, S.; Nishtar, S.; Hafeez, A.; Buehler, W.; Bile, K. M.; Sabih, F. (2010). "Implementing the district health system in the framework of primary health care in Pakistan: can the evolving reforms enhance the pace towards the Millennium Development Goals?". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 16 (Supp): 132–144. doi:10.26719/2010.16.Supp.132. hdl:10665/118033. PMID 21495599.

- ^ "Pakistan acts to reduce child deaths from pneumonia". who.int. World Health Organization (WHO), International. Archived from the original on 13 April 2001.

- ^ "Fighting hepatitis in Pakistan".

- ^ Abbas, Zaigham; Jafri, Wasim; Hamid, Saeed; Pakistan Society for the Study of Liver, Diseases. (March 2010). "Management of hepatitis B: Pakistan Society for the Study of Liver Diseases (PSSLD) practice guidelines" (PDF). Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 20 (3): 198–201. PMID 20392385.

- ^ "National TB Control Program". National Institute of Health Islamabad.

- ^ "Tuberculosis Programmes". WHO EMRO.

- ^ "National Malaria Control Programme". Ministry of Health, Pakistan. Retrieved 7 September 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ ""It was just the perfect storm for malaria" – Pakistan responds to surge in cases following the 2022 floods". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan Coronavirus: 346,476 Cases and 7,000 Deaths - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ a b Jafar, Tazeen H; Haaland, Benjamin A; Rahman, Atif; Razzak, Junaid A; Bilger, Marcel; Naghavi, Mohsen; Mokdad, Ali H; Hyder, Adnan A (June 2013). "Non-communicable diseases and injuries in Pakistan: strategic priorities". The Lancet. 381 (9885): 2281–2290. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60646-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 23684257. S2CID 22853989.

- ^ Pakistan World Health Organization

- ^ "www.who.int" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b Tabassum, Shehroze; Naeem, Aroma; Nazir, Abubakar; Naeem, Farhan; Gill, Saima; Tabassum, Shehram (April 2023). "Year-round dengue fever in Pakistan, highlighting the surge amidst ongoing flood havoc and the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review". Annals of Medicine & Surgery. 85 (4): 908–912. doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000000418. ISSN 2049-0801. PMC 10129218. PMID 37113909.

- ^ "Dengue Expert Advisory Group". Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "'Dengue Mukao Campaign': students urged to play vanguard role". Brecorder. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Dengue fever – Pakistan". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Measles - number of reported cases". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ CDCGlobal (15 September 2023). "Global Measles Outbreaks". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Tariq, Samiuddin; Niaz, Faizan; Afzal, Yusra; Tariq, Rabbia; Nashwan, Abdulqadir J.; Ullah, Irfan (2022). "Pakistan at the precipice: The looming threat of measles amidst the COVID-19 pandemic". Frontiers in Public Health. 10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1000906. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 9720314. PMID 36478715.

- ^ "Poliomyelitis (polio)". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Country Profiles (Pakistan)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Nine polio cases confirmed in 2018 - Pakistan". ReliefWeb. 11 January 2019.

- ^ "Statement of the Thirty-sixth Meeting of the Polio IHR Emergency Committee". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan Polio Eradication Initiative National Emergency Action Plan 2021-2023" (PDF). Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic" (PDF). June 1998.

- ^ Burki, Talha (April 2008). "New government in Pakistan faces old challenges". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 217–218. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(08)70054-9. PMID 18459182.

- ^ Shah, SA. Tropical Medicine Symposium, The Aga Khan University and the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine, 2008.

- ^ "HIV cases–Pakistan". WHO. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019.

- ^ Tufail, Muhammad; Wu, Changxin (1 June 2023). "Exploring the Burden of Cancer in Pakistan: An Analysis of 2019 Data". Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health. 13 (2): 333–343. doi:10.1007/s44197-023-00104-5. ISSN 2210-6014. PMC 10272049. PMID 37185935.

- ^ "The necessity of awareness of Breast Cancer amongst women in Pakistan". Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 59 (11). November 2009.

- ^ Menhas, Rashid; Umer, Shumaila (2015). "Breast Cancer among Pakistani Women". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 44 (4): 586–587. PMC 4441973. PMID 26056679.

- ^ Ahmad, Zubair; Idrees, Romana; Fatima, Saira; Uddin, Nasir; Ahmed, Arsalan; Minhas, Khurram; Memon, Aisha; Fatima, Syeda Samia; Arif, Muhammad; Hasan, Sheema; Ahmed, Rashida; Pervez, Shahid; Kayani, Naila (11 April 2016). "Commonest Cancers in Pakistan - Findings and Histopathological Perspective from a Premier Surgical Pathology Center in Pakistan". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 17 (3): 1061–1075. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.3.1061. PMID 27039726.

- ^ Aman, Shahbaz; Nadeem, Muhammad; Mahmood, Khalid; Ghafoor, Muhammad B. (1 October 2017). "Pattern of skin diseases among patients attending a tertiary care hospital in Lahore, Pakistan". Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 12 (5): 392–396. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.04.007. PMC 6694895. PMID 31435269.

- ^ http://www.mopw.gov.pk/event3.html Archived 26 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Population Policy of Government of Pakistan

- ^ a b http://resdev.org/Docs/01fpoverview.pdf Archived 27 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Overview of Family Planning in Pakistan

- ^ "Family planning". UNFPA Pakistan. 13 December 2017.

- ^ http://resdev.org/Docs/01fpservices.pdf[permanent dead link] Family Planning Services in Pakistan

- ^ "What unmet need for family planning means in Pakistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Shah, N. M.; Wang, W.; Bishai, D. M. (5 July 2011). "Comparing private sector family planning services to government and NGO services in Ethiopia and Pakistan: how do social franchises compare across quality, equity and cost?". Health Policy and Planning. 26 (Suppl. 1): i63–i71. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr027. PMC 3606031. PMID 21729919.

- ^ "Pakistan". Family Planning 2020. 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births)". www.who.int. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Pakistan 2019 Maternal Mortality Survey Summary Report" (PDF). Demographic Health Survey. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Births attended by skilled health personnel (%)". www.who.int. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Under-five mortality rate (per 1000 live births) (SDG 3.2.1)". www.who.int. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Neonatal mortality rate (0 to 27 days) per 1000 live births) (SDG 3.2.2)". www.who.int. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "SDG Indicators — SDG Indicators". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "GBD Compare". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "National Nutrition Survey Pakistan (NNS 2018)" (PDF). UNICEF.

- ^ "National Nutrition Survey Pakistan 2011 (NNS 2011)" (PDF). Government of Pakistan.

- ^ Streib, Lauren (2 August 2007). "World's Fattest Countries". Forbes. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007.

- ^ "One in four adults is overweight or clinically obese". Gulf News. 17 December 2006.

- ^ "Epidemic of obesity in Pakistan - one in four Pakistanis may be overweight or obese". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Nanan, D.J. (2002). "The Obesity Pandemic - Implications for Pakistan". Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 52 (8): 342–346. PMID 12481671.

- ^ "Fat is more dangerous for South Asians: Study - The Express Tribune". 29 July 2011.

- ^ a b c "WHO EMRO | Expanded Programme on Immunization | Programmes | Pakistan". www.emro.who.int. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Vaccine Preventable Diseases – Federal Directorate of Immunization, Pakistan". Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2022 revision" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Garrelts, Heiko (2012), "Organization Profile – Germanwatch", Routledge Handbook of the Climate Change Movement, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9780203773536.ch31, ISBN 978-0-203-77353-6, retrieved 19 September 2023

- ^ Malik, Sadia Mariam; Awan, Haroon; Khan, Niazullah (3 September 2012). "Mapping vulnerability to climate change and its repercussions on human health in Pakistan". Globalization and Health. 8 (1): 31. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-8-31. ISSN 1744-8603. PMC 3477077. PMID 22938568.

- ^ "Drug contamination: death toll exceeds 120 in Pakistan hospital". Reactions Weekly (1389): 3. February 2012. doi:10.2165/00128415-201213890-00006. ISSN 0114-9954. S2CID 195169881.

- ^ "Heat Wave Death Toll Rises to 2,000 in Pakistan's Financial Hub". Bloomberg.com. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Devastating floods in Pakistan". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Zaidi, Shehla; Memon, Zahid (July 2023). "Pakistan floods: breaking the logjam of spiraling health shocks". eBioMedicine. 93: 104707. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104707. ISSN 2352-3964. PMC 10363445. PMID 37394380.

- ^ Qamer, Faisal Mueen; Abbas, Sawaid; Ahmad, Bashir; Hussain, Abid; Salman, Aneel; Muhammad, Sher; Nawaz, Muhammad; Shrestha, Sravan; Iqbal, Bilal; Thapa, Sunil (14 March 2023). "A framework for multi-sensor satellite data to evaluate crop production losses: the case study of 2022 Pakistan floods". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 4240. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.4240Q. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-30347-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10015072. PMID 36918608.

- ^ Pakistan: Floods response update, February 2023 (Report). FAO. 2 March 2023. doi:10.4060/cc4663en.

- ^ "Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency". environment.gov.pk. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan floods: Around 100,000 people evacuated in Punjab". Le Monde.fr. 23 August 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.