Hacksilver

.jpg/440px-Hack_silver_(cropped).jpg)

Hacksilver (sometimes referred to as hacksilber) consists of fragments of cut and bent silver items that were used as bullion or as currency by weight during the Middle Ages.

Use

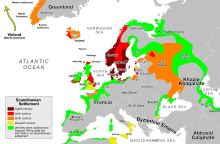

Hacksilver was common among the Norsemen or Vikings, as a result of both their raiding and trade. Hacksilver may also have been used by Romans in their dealings with Pictish tribes.[1] The name of the ruble, the basic unit of modern Russian currency, is derived from the Russian verb рубить ('rubit'), meaning "to chop", from the practice of the Rus', described by Ahmad ibn Fadlan visiting the Volga Vikings in 922.[citation needed] An example of the related Viking weighing scale with weights was found on the Isle of Gigha.[2] Hacksilver may be derived from silver tableware, Roman or Byzantine, church plate and silver objects such as reliquaries or book-covers, and jewellery from a range of areas. Hoards may typically include a mixture of hacksilver, coins, ingots and complete small pieces of jewellery.

Hoards of hacksilver are also well known in pre and post-coinage antiquity, in European and Near Eastern contexts. The Cisjordan Corpus (c.1200-586 BC) is the largest identified concentration of pre-coinage hacksilver hoards, and provides key evidence for the Phoenician and wider Near Eastern roots of the development and proliferation of the earliest silver coinages in the Greek world and western tradition.

The widespread adoption of Greek silver coinages by c. 480 BC appears to have developed first out of cooperative relations between Greeks and Phoenicians, then partly as a competitive, culturally consolidating response to earlier Phoenician expansion and domination of silver trade, which had been conducted with hacksilver. Within the Cisjordan Corpus, a concentration of hacksilver hoards occurs in a part of southern Phoenicia that was recorded in antiquity as a territory of the Shardana tribes of Sea Peoples associated with Sardinia. Thompson, in her analyses of the hacksilver pieces, relates this textual evidence to lead isotope ratios that have ore signatures matching Sardinian ores. This is the first recognized material evidence linking the two regions in this critical period.[3] The same hacksilver hoards have provided the first recognized provenance-evidence for far-reaching contact between Europe and Asia related to the prehistoric trafficking of metals.[4][5]

Hacksilver hoards

- The 4th or 5th century hoard of Traprain Law (Traprain Treasure) consists of four silver coins and over 24 kilograms of sliced-up Late Roman silver tableware, much of it of very high quality. Whether this was handed over by Romans to the Pictish occupants of the site, or the products of raids on Roman Britain, is unclear.

- The Vale of York hoard includes 617 silver coins and hacksilver.

- The Cuerdale Hoard includes 8,600 items, silver coins and hacksilver.[6]

- The Skaill Hoard, the largest Viking Age silver hoard found in Scotland, consists of over 100 items, including jewelry, a few coins and assorted hacksilver. The hoard, dated to between 950 and 970, was found in Skaill, Sandwick, Orkney, in 1858.[7][8][9]

- The main Penrith Hoard is of Viking-period penannular brooches, but a separate hoard found very close by includes many pieces of hacksilver.

- The 'southern Phoenician' hacksilver hoards in the Cisjordan Corpus were found at Ein Hofez, Tell Keisan, Dor and Akko.[10]

Sources

- Graham-Campbell, James; Batey, Colleen E. (1998). Vikings in Scotland: An Archaeological Survey. Edinburgh University Press. p. 243. ISBN 0-7486-0641-6.

- James Graham-Campbell: The Viking-age silver and gold hoards of Scandinavian character from Scotland

- M. Bogucki: Reasons for hiding Viking Age hack silver hoards[permanent dead link]

- Hacksilver in the database of the National Museums of Scotland

- Hacksilver in the database of the British Museum Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Hacksilber Project

References

- ^ "'Significant' Roman silver hoard found in Fife by teenager". BBC News. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "Viking weights". University of Glasgow.

- ^ Christine M. Thompson 2011: 'Silver in the age of iron: an overview', in C. Giardino (ed.) Archeometallurgia: dalla conoscenza alla fruizione. Atti del convegno Cavallino, Lecce, 22-25/05/2006 Bari: Edipuglia. 121-32.

- ^ Thompson, C.M; Skaggs, S. (2013). "King Solomon's Silver? Southern Phoenician Hacksilber Hoards and the Location of Tarshish". Internet Archaeology. 35 (35). doi:10.11141/ia.35.6.

- ^ Balmuth, M.S. and Thompson, C.M. 2000, 'Hacksilber: recent approaches to the study of hoards of uncoined silver', in B. Klengel and B. Weisser (eds) Acts of the XIIth International Numismatic Congress, 9-13th September, Berlin, 1997 = XII. Internationaler Numismatischer Kongress, Akten Berlin. 159-69.

- ^ "BBC - History - Ancient History in depth: The Cuerdale Hoard". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "National Museums of Scotland - Hacksilver". nms.scran.ac.uk.

- ^ "Orkneyjar - The Skaill Viking Hoard in Sandwick, Orkney". www.orkneyjar.com.

- ^ Graham-Campbell, J A (1975–76). "The Viking-age silver and gold hoards of Scandinavian character from Scotland" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 107: 114–135. doi:10.9750/PSAS.107.114.135.

- ^ "Internet Archaeol. 35. Thompson and Skaggs. Initial assessments". intarch.ac.uk.