Gezer calendar

| Gezer calendar | |

|---|---|

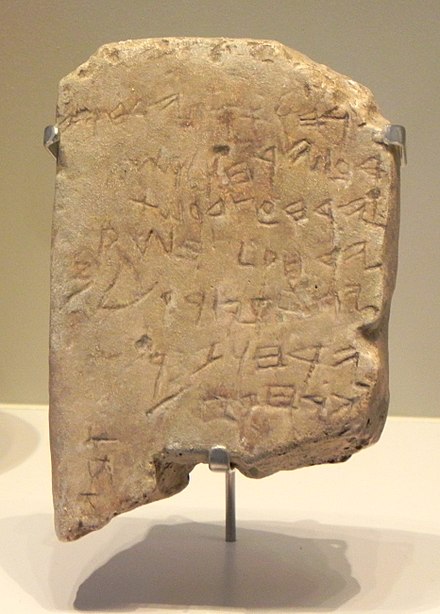

The calendar in its current location | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Size | 11.1 × 7.2 cm |

| Writing | Phoenician or paleo-Hebrew |

| Created | c. 10th century BCE |

| Discovered | 1908 |

| Present location | Istanbul Archaeology Museums |

| Identification | 2089 T |

The Gezer calendar is a small limestone tablet with an early Canaanite inscription discovered in 1908 by Irish archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister in the ancient city of Gezer, 20 miles west of Jerusalem. It is commonly dated to the 10th century BCE, although the excavation was unstratified[1] and its identification during the excavations was not in a "secure archaeological context", presenting uncertainty around the dating.[2]

Scholars are divided as to whether the language is Phoenician or Hebrew and whether the script is Phoenician (or Proto-Canaanite) or paleo-Hebrew. Koller argued that the language is Northern Hebrew.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "to apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable".

The inscription is not a formal calendar, as it describes agricultural seasons with imprecise dates, rather than precise divisions of time as would be required for a ritual or bureaucratic calendar. As such, some of the time units comprise two months rather than one, and none are referred to by the month numbers or names known from other sources.[9]

Inscription

The calendar is inscribed on a limestone plaque and describes monthly or bi-monthly periods and attributes to each a duty such as harvest, planting, or tending specific crops.

The inscription, known as KAI 182, is in Phoenician or paleo-Hebrew script:

𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤅𐤀𐤎𐤐.𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤅𐤆

𐤓𐤏.𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤅𐤋𐤒𐤔

𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤏𐤑𐤃𐤐𐤔𐤕

𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤒𐤑𐤓𐤔𐤏𐤓𐤌

𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤒𐤑𐤓𐤅𐤊𐤋

𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤅𐤆𐤌𐤓

𐤉𐤓𐤇𐤒𐤑

- 𐤉𐤁𐤀

Which in equivalent square Hebrew letters is as follows:

- ירחואספ ירחוז

- רע ירחולקש

- ירחעצדפשת

- ירחקצרשערמ

- ירחקצרוכל

- ירחוזמר

- ירחקצ

- אבי (ה)

This corresponds to the following transliteration, with spaces added for word divisions:

- yrḥw ʾsp yrḥw z

- rʿ yrḥw lqš

- yrḥ ʿṣd pšt

- yrḥ qṣr šʿrm

- yrḥ qṣrw kl

- yrḥw zmr

- yrḥ qṣ

- ʾby [h]

The text has been translated as:

- Two months gathering (October, November — in the Hebrew calendar Tishrei, Cheshvan)

- Two months planting (December, January — Kislev, Tevet)

- Two months late sowing (February, March — Shvat, Adar)

- One month cutting flax (April — Nisan)

- One month reaping barley (May — Iyar)

- One month reaping and measuring grain (June — Sivan)

- Two months pruning (July, August — Tammuz, Av)

- One month summer fruit (September — Elul)

- Abij [ah][10]

Scholars have speculated that the calendar could be a schoolboy's memory exercise, the text of a popular folk song or a children's song. Another possibility is something designed for the collection of taxes from farmers.

The scribe of the calendar is probably "Abijah", whose name means "Yah (a shorter form of the Tetragrammaton) is my father". This name appears in the Bible for several individuals, including a king of Judah (1 Kings 14:31). If accurate, then it would be an early attestation of the name YHWH, predating the Mesha Stele by more than a century.[11]

History

The calendar was discovered in 1908 by R.A.S. Macalister of the Palestine Exploration Fund while excavating the ancient Canaanite city of Gezer, 20 miles west of Jerusalem.

The Gezer calendar is currently displayed at the Museum of the Ancient Orient, a Turkish archaeology museum,[12][13] as is the Siloam inscription and other archaeological artifacts unearthed before World War I. A replica of the Gezer calendar is on display at the Israel Museum, Israel.

See also

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- List of ancient Near Eastern scribes

- List of languages by first written accounts

- Archaeology of Israel

References

- ^ Tappy, Ron E.; McCarter, P. Kyle; Lundberg, Marilyn J.; Zuckerman, Bruce (2006). "An abecedary of the mid-tenth century B.C.E. from the Judaean Shephelah". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 344 (344): 41. doi:10.1086/BASOR25066976. JSTOR 25066976. S2CID 163300154.

...compromised archaeological contexts (e.g. the unstratified Gezer calendar...

- ^ Aaron Demsky (2007), Reading Northwest Semitic Inscriptions, Near Eastern Archaeology 70/2. Quote: "The first thing to consider when examining an ancient inscription is whether it was discovered in context or not. It is obvious that a document purchased on the antiquities market is suspect. If it was found in an archeological site, one should note whether it was found in its primary context, as with the inscription of King Achish from Ekron, or in secondary use, as with the Tel Dan inscription. Of course texts that were found in an archaeological site, but not in a secure archaeological context present certain problems of exact dating, as with the Gezer Calendar."

- ^ Koller, Aaron (2013). "Ancient Hebrew מעצד and עצד in the Gezer Calendar". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 72 (2): 179–193. doi:10.1086/671444. S2CID 161247763.

- ^ The Calendar Tablet from Gezer, Adam L Bean, Emmanual School of Religion Archived March 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Is it “Tenable”?, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review Archived December 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spelling in the Hebrew Bible: Dahood memorial lecture, By Francis I. Andersen, A. Dean Forbes, p56

- ^ Pardee, Dennis. "A Brief Case for the Language of the 'Gezer Calendar' as Phoenician". Linguistic Studies in Phoenician, ed. Robert D. Holmstedt and Aaron Schade. Winona Lake: 43.

- ^ Chris A. Rollston (2010). Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age. Society of Biblical Lit. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-58983-107-0.

- ^ Seth L. Sanders, “Writing and Early Iron Age Israel: Before National Scripts, Beyond Nations and States,” in Literate Culture and Tenth-Century Canaan: The Tel Zayit Abecedary in Context, ed. Ron E. Tappy and P. Kyle McCarter, (Winona Lake, IN, 2008), p. 100–102

- ^ Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0199830114.

- ^ Hoffmeier, James (2005). Ancient Israel in Sinai. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 240–241.

- ^ Gezer calendar Archived 2012-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Istanbul Archaeological Museums, Artifacts Archived 2012-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Albright, W.F. "The Gezer Calendar" in Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (BASOR). 1943. Volume 92:16–26. Original description of the find.

- Koller, Aaron. "Ancient Hebrew מעצד and עצד in the Gezer Calendar," Journal of Near Eastern Studies 72 (2013), 179–193, available at https://repository.yu.edu/handle/20.500.12202/4440.

- Sivan, Daniel "The Gezer calendar and Northwest Semitic linguistics", Israel Exploration Journal 48,1-2 (1998) 101–105. An up-to-date linguistic analysis of this text.

- Dever, William G. “Gezer”. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East vol. 2, Editor in Chief Eric M. Meyers, 396–400. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Pardee, Dennis. “Gezer Calendar”. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East vol. 2, Editor in Chief Eric M. Meyers, 396–400. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

External links

- Details of the calendar including transcription and translation. Archived 4 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Another translation and a picture of the calendar.