Garcilaso de la Vega (poet)

Garcilaso de la Vega | |

|---|---|

Portrait at the New Gallery, Kassel | |

| Born | García Laso de la Vega 15 February 1498–1503 Toledo, Castile (present-day Spain) |

| Died | 14 October 1536 (aged 33–38) Nice, Duchy of Savoy (present-day France) |

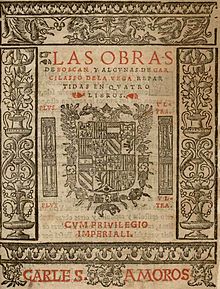

Garcilaso de la Vega, KOS (c. 1501 – 14 October 1536) was a Spanish soldier and poet. Although not the first or the only one to do so, he was the most influential poet to introduce Italian Renaissance verse forms, poetic techniques, and themes to Spain. He was well known in poetic circles during his lifetime, and his poetry has continued to be popular without interruption until the present. His poetry was published posthumously by Juan Boscán in 1543, and it has been the subject of several annotated editions, the first and most famous of which appeared in 1574.

Biography

Garcilaso was born in the Spanish city of Toledo between 1498 and 1503.[1] Clavería Boscán affirms he was born between 1487 and 1492,[2] and another sources affirms he was born in 1501.[3] His father Garcilaso de la Vega, the third son of Pedro Suárez de Figueroa, was a nobleman and ambassador in the royal court of the Catholic Monarchs.[4] His mother's name was Sancha de Guzmán.[5]

Garcilaso was the second son which meant he did not receive the mayorazgo (entitlement) to his father's estate. However, he spent his younger years receiving an extensive education, mastered five languages (Spanish, Greek, Latin, Italian and French), and learned how to play the zither, lute and the harp. When his father died in 1509, Garcilaso received a sizeable inheritance.

After his schooling, he joined the military in hopes of joining the royal guard. He was named "contino" (imperial guard) of Charles V in 1520, and he was made a member of the Order of Santiago in 1523.

There were a few women in the life of this poet. His first lover was Guiomar Carrillo, with whom he had a child. He had another suspected lover named Isabel Freire, who was a lady-in-waiting of Isabel of Portugal, but this is today regarded as mythical.[6] In 1525, Garcilaso married Elena de Zúñiga, who served as a lady-in-waiting for the King's favorite sister, Leonor. Their marriage took place in Garcilaso's hometown of Toledo in one of the family's estates. He had six children: Lorenzo, an illegitimate child with Guiomar Carrillo, Garcilaso, Íñigo de Zúñiga, Pedro de Guzmán, Sancha, and Francisco.

Garcilaso's military career meant that he took part in the numerous battles and campaigns conducted by Charles V across Europe. His duties took him to Italy, Germany, Tunisia and France. In 1532 for a short period he was exiled to a Danube island where he was the guest of the Count György Cseszneky, royal court judge of Győr. Later in France, he would fight his last battle. The King desired to take control of Marseille and eventually control of the Mediterranean Sea, but this goal was never realized. Garcilaso de la Vega died on 14 October 1536 in Nice, after suffering 25 days from an injury sustained in a battle at Le Muy. His body was first buried in the Church of St. Dominic in Nice, but two years later his wife had his body moved to the Church of San Pedro Martir in Toledo.

Works

Garcilaso de la Vega is best known for his tragic love poetry that contrasts the playful poetry of his predecessors. He seemed to progress through three distinct episodes of his life which are reflected in his works. During his Spanish period, he wrote the majority of his eight-syllable poems; during his Italian or Petrarchan period, he wrote mostly sonnets and songs; and during his Neapolitan or classicist period, he wrote his other more classical poems, including his elegies, letters, eclogues and odes. Influenced by many Italian Renaissance poets, Garcilaso adapted the eleven-syllable line to the Spanish language in his sonetos (sonnets), mostly written in the 1520s, during his Petrarchan period. Increasing the number of syllables in the verse from eight to eleven allowed for greater flexibility. In addition to the sonetos, Garcilaso helped to introduce several other types of stanzas to the Spanish language. These include the estancia, formed by eleven- and seven-syllable lines; the "lira", formed by three seven-syllable and two eleven-syllable lines; and endecasílabos sueltos, formed by unrhymed eleven-syllable lines.

Throughout his life, Garcilaso de la Vega wrote various poems in each of these types. His works include: forty Sonetos (Sonnets), five Canciones (Songs), eight Coplas (Couplets), three Églogas (Eclogues), two Elegías (Elegies), and the Epístola a Boscán (Letter to Boscán). Allusions to classical myths and Greco-Latin figures, great musicality, alliteration, rhythm and an absence of religion characterize his poetry. It can be said that Spanish poetry was never the same after Garcilaso de la Vega. His works have influenced the majority of subsequent Spanish poets, including other major authors of the period like Jorge de Montemor, Luis de León, John of the Cross, Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Luis de Góngora and Francisco Quevedo.

For example: (égloga Tercera):

- Más a las veces son mejor oídos

- el puro ingenio y lengua casi muda,

- testigos limpios de ánimo inocente,

- que la curiosidad del elocuente.

He was very good at transmitting the sense of life into writing, in many poems including his «dolorido sentir»:

- No me podrán quitar el dolorido

- sentir, si ya del todo

- primero no me quitan el sentido.

We see the shift in traditional belief of Heaven as influenced by the Renaissance, which is called "neo-Platonism," which tried to lift love to a spiritual, idealistic plane, as compared to the traditional Catholic view of Heaven. (Égloga primera):

- Contigo mano a mano

- busquemos otros prados y otros ríos,

- otros valles floridos y sombríos,

- donde descanse, y siempre pueda verte

- ante los ojos míos,

- sin miedo y sobresalto de perderte. (Égloga primera)

He has enjoyed a revival of influence among 21st century pastoral poets such as Seamus Heaney, Dennis Nurkse, and Giannina Braschi.

Literary references

.jpg/440px-Toledo7_(17937739432).jpg)

Garcilaso is mentioned in multiple works by Miguel de Cervantes. In the second volume of Don Quixote, the protagonist quotes one of the poet's sonnets.[7] In El licenciado Vidriera, Tomás Rodaja carries a volume of Garcilaso on his journey across Europe.

The title of Pedro Salinas's sequence of poems La voz a ti debida is taken from Garcilaso's third eclogue.

In the novel Of Love and Other Demons by Gabriel García Márquez, one of the main characters, Father Cayetano Delaura, is an admirer of Garcilaso de la Vega. In the novel, which takes place in 18th-century colonial Colombia, Delaura is forced to give up being a priest because of his tragic love affair.

Puerto Rican poet Giannina Braschi wrote both a poetic treatise on Garcilaso de la Vega's Eclogues, as well as a book of poems in homage to the Spanish master, entitled Empire of Dreams.

Modern translations

- The Odes and Sonnets of Garcilaso de la Vega, trans James Cleugh, (London: Aquila, 1930)

Further reading

- Creel, Bryant. "Garcilaso de la Vega". Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 318: Sixteenth-Century Spanish Writers. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Gregory B. Kaplan, University of Tennessee. Gale, 2005. pp. 62–82.

- Braschi, Giannina. “La metamorfosis del ingenio en la Egloga III de Garcilaso." Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispanicos, 4.1, 1979.

References

- ^ Vallvey, Angela (15 July 2015). El arte de amar la vida. Kailas Editorial. p. 49. ISBN 9788416023776.

- ^ Pérez López, José Luis (2000). "La fecha de nacimiento de Garcilaso de la Vega a la luz de un nuevo documento biográfico" (PDF). Criticón. 78. Centro Virtual Cervantes: 45–57. ISBN 84-690-3363-8. ISSN 0247-381X.

- ^ "Garcilaso de la Vega" (PDF). Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Ordenación Universitaria (in Spanish). Xunta de Galicia. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Mazo Romero, Fernando. "Los Suárez de Figueroa y el señorío de Feria" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Sevilla: 113–164.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Garcilaso de la Vega". Litoral (61/63). Revista Litoral S.A.: 63–67. 1976–1977. JSTOR 43398752.

- ^ Darst, David H. (1979). "Garcilaso´s Love for Isabel Freire: The Creation of a Myth". Journal of Hispanic Philology. 3: 261–268.

- ^ Herreid, Grant. "The Musical World of Don Quixote" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

External links

- Works by Garcilaso de la Vega at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Garcilaso de la Vega at Internet Archive

- Works by Garcilaso de la Vega at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Page about Garcilaso de la Vega "La Página de Garcilaso en Internet." 2006. La Asociación de Amigos de Garcilaso de la Vega (Toledo, España). (in Spanish)

- "Multiculturalism Gone Wrong: Spain in the Renaissance", Alix Ingber, (adapted from a lecture). <http://www.dean.sbc.edu/ingber.html>. [Last updated: January 19, 1998].

- "Spanish Literature (Archived 2009-11-01)," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006.