Elysium quadrangle

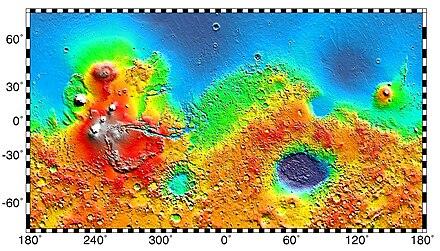

Map of Elysium quadrangle from Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) data. The highest elevations are red and the lowest are blue. | |

| Coordinates | 15°00′N 202°30′W / 15°N 202.5°W / 15; -202.5 |

|---|---|

The Elysium quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Elysium quadrangle is also referred to as MC-15 (Mars Chart-15).[1]

The name Elysium refers to a place of reward (Heaven), according to Homer in the Odyssey.[2]

The Elysium quadrangle covers the area between 180° to 225° west longitude and 0° to 30° north latitude on Mars. The northern part of Elysium Planitia, a broad plain, is in this quadrangle. The Elysium quadrangle includes a part of Lucus Planum. A small part of the Medusae Fossae Formation lies in this quadrangle. The largest craters in this quadrangle are Eddie, Lockyer, and Tombaugh. The quadrangle contains the major volcanoes Elysium Mons and Albor Tholus, part of a volcanic province of the same name, as well as river valleys—one of which, Athabasca Valles may be one of the youngest on Mars. On the east side is an elongated depression called Orcus Patera. A large lake may once have existed in the south near Lethe Vallis and Athabasca Valles.[3]

The InSight lander touched down in the southern part of this quadrangle in 2018 to conduct geophysical studies.

Volcanoes

The Elysium quadrangle contains the volcanoes Elysium Mons and Albor Tholus.

David Susko and his colleagues at Louisiana State University analyzed geochemical and surface morphology data from Elysium using instruments on board NASA's Mars Odyssey Orbiter (2001) and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (2006). Through crater counting, they found differences in age between the northwest and the southeast regions of Elysium—about 850 million years of difference. They also found that the younger southeast regions are geochemically different from the older regions, and that these differences related to igneous processes, not secondary processes like the interaction of water or ice with the surface of Elysium in the past. "We determined that while there might have been water in this area in the past, the geochemical properties in the top meter throughout this volcanic province are indicative of igneous processes," Susko said. "We think levels of thorium and potassium here were depleted over time because of volcanic eruptions over billions of years. The radioactive elements were the first to go in the early eruptions. We are seeing changes in the mantle chemistry over time." "Long-lived volcanic systems with changing magma compositions are common on Earth, but an emerging story on Mars," said James Wray, study co-author and associate professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Georgia Tech. Overall, these findings indicate that Mars is a much more geologically complex body than originally thought, perhaps due to various loading effects on the mantle caused by the weight of giant volcanoes. For decades, we saw Mars, as a lifeless rock, full of craters with a number of long inactive volcanoes. We had a very simple view of the red planet. Finding a variety of igneous rocks demonstrates that Mars has the potential for useful resource utilization and a capacity to sustain a human population on Mars. "It's much easier to survive on a complex planetary body bearing the mineral products of complex geology than on a simpler body like the moon or asteroids."[4][5]

Much of the area near the volcanoes is covered with lava flows, some can even be shown approaching, then stopping upon reaching higher ground. (See pictures below for examples) Sometimes when lava flows the top cools quickly into a solid crust. However, the lava below often still flows, this action breaks up the top layer making it very rough.[6] Such rough flow is called aa.

Research, published in January 2010, described the discovery of a vast single lava flow, the size of the state of Oregon, that "was put in place turbulently over the span of several weeks at most."[7] This flow, near Athabasca Valles, is the youngest lava flow on Mars. It is thought to be of Late Amazonian Age.[8] Other researchers disagree with this idea. Under Martian conditions lava should not stay fluid very long.[3]

Some areas in the Elysium quadrangle are geological young and have surfaces that are hard to explain. Some have called them Platy-Ridged-Polygonized terrain. The surface has been suggested to be from pack ice, basalt lava, or a muddy flow. Using HiRISE images the heights of the ridges of the surface were measured. Most were less than 2 meters. This is far smaller than what is expected from lava flows. The high resolution photos demonstrated that the material seemed to flow which would not occur with pack ice. So, the researchers concluded that muddy flows cover the surface.[9]

-

Map of Elysium quadrangle. Elysium Mons and Albor Tholus are large volcanoes.

-

Lava flow in Elysium. There are many lava flows in Elysium. In this one, the lava flowed toward the upper right. Image taken by Mars Global Surveyor, under the MOC Public Targeting Program.

-

Lava flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Lava flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Dark slope streaks are also visible.

-

Close view of lava flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Dark slope streaks are also visible.

-

Pits with lava flow at the top of the picture Image was taken with HiRISE, under HiWish program

-

Lava flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Lava flows in Elysium as seen by HiRISE. Upper part of image shows lava that solidified on the top then crumpled as lava still moved.

-

Lava flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Lava rafts, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Cones in Athabasca Vallis, as seen by HiRISE. Cones were formed from lava interacting with ice. Larger cones in upper image were produced when water/steam forced its way through thicker layer of lava. Difference between highest elevation (red) to lowest (dark blue) is 170 m (560 ft).

Rootless cones

So-called "rootless cones" are caused by explosions of lava with ground ice under the flow.[10][11][12] The ice melts and turns into a vapor that expands in an explosion that produces a cone or ring. Features like these are found in Iceland, when lavas cover water-saturated substrates.[13][11][14]

-

Wide view of field of rootless cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of field of rootless cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Rootless Cones, as seen by HiRISE. The chains of rings are interpreted to be caused by crust moving over a source of steam. The steam was produced by lava interacting with water ice.[15] [16]

-

Rootless Cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program These group of rings or cones are believed to be caused by lava flowing over water ice or ground containing water ice. The ice quickly changes to steam which blows out a ring or cone.

-

Rootless Cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. These group of rings or cones are believed to be caused by lava flowing over water ice or ground containing water ice. The ice quickly changes to steam which blows out a ring or cone. Here the kink in the chain may have been caused by the lava changing direction.

-

Rootless Cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. These group of rings or cones are believed to be caused by lava flowing over water ice or ground containing water ice. The ice quickly changes to steam which blows out a ring or cone. Here the kink in the chain may have been caused by the lava changing direction. Some of the forms do not have the shape of rings or cones because maybe the lava moved too quickly; thereby not allowing a complete cone shape to form.

-

Cones and possible maars, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Wide view of field of rootless cones in Phlegra region, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of rootless cones with tails that suggest lava was moving toward the Southwest over ice-rich ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of cones with the size of a football field shown, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Cones and surface of lava, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. These cones probably formed when hot lava flowed over ice-rich ground.

-

Close view of cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. These cones probably formed when hot lava flowed over ice-rich ground.

Layers

The Elysium Fossae contain layers, also called strata. Many places on Mars show rocks arranged in layers. Sometimes the layers are of different colors. Light-toned rocks on Mars have been associated with hydrated minerals like sulfates. The Mars rover Opportunity examined such layers close-up with several instruments. Pictures taken from orbiting spacecraft show that some layers of rocks seem to break up into fine dust; consequently these rocks are probably composed of small particles. Other layers break up into large boulders, so they are probably much harder. Basalt, a volcanic rock, is thought comprise the layers that form boulders. Basalt has been identified on Mars in many places. Instruments on orbiting spacecraft have detected clay (also called phyllosilicates) in some layers. Scientists are excited about finding hydrated minerals such as sulfates and clays on Mars because they are usually formed in the presence of water.[17] Places that contain clays and/or other hydrated minerals would be good places to look for evidence of life.[18]

Rock can be formed into layers in a variety of ways. Volcanoes, wind, or water can produce layers.[19] Layers can be hardened by the action of groundwater. Martian ground water probably moved hundreds of kilometers, and in the process it dissolved many minerals from the rock it passed through. When ground water surfaces in low areas containing sediments, water evaporates in the thin atmosphere and leaves behind minerals as deposits and/or cementing agents. Consequently, layers of dust could not later easily erode away since they were cemented together.

,

-

Layers in Monument Valley. These are accepted as being formed, at least in part, by water deposition. Since Mars contains similar layers, water remains as a major cause of layering on Mars.

-

Angular Unconformity in Cerberus Fossae, as seen by HiRISE. Click on image to see the angles of the layers.

-

Wrinkle Ridge and pit showing layers, as seen by HiRISE. Click on image to see layers. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Wide view of Iberus Vallis, as seen by HiRISE. Imagine taking a walk in these canyons and looking up at the layers.

-

Detail from the center of the previous image, as seen by HiRISE

-

Layers around streamlined knob, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Layers around base of mound, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Layers in old crater rim, in Marte Vallis as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of layers from previous image, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some dark slope streaks are visible.

-

Layers and dark slope streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrow indicates the small spot where the streak started.

-

Layers and streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. One streak is curved.

-

Wide view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Layered mound with streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of layers on crater wall, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Fossae/pit craters

The Elysium quadrangle is home to large troughs (long narrow depressions) called fossae in the geographical language used for Mars. Troughs are created when the crust is stretched until it breaks. The stretching can be due to the large weight of a nearby volcano. Fossae/pit craters are common near volcanoes in the Tharsis and Elysium system of volcanoes.[20] A trough often has two breaks with a middle section moving down, leaving steep cliffs along the sides; such a trough is called a graben.[21] Lake George, in northern New York State, is a lake that sits in a graben. Pits are produced when material collapses into the void that results from the stretching. Pit craters do not have rims or ejecta around them, like impact craters do. Studies have found that on Mars a fault may be as deep as 5 km (3.1 mi); that is, the break in the rock goes down to 5 km. Moreover, the crack or fault sometimes widens or dilates. This widening causes a void to form with a relatively high volume. When material slides into the void, a pit crater or a pit crater chain forms. On Mars, individual pit craters can join to form chains or even to form troughs that are sometimes scalloped.[22] Other ideas have been suggested for the formation of fossae and pit craters. There is evidence that they are associated with dikes of magma. Magma might move along, under the surface, breaking the rock, and more importantly melting ice. The resulting action would cause a crack to form at the surface. Pit craters are not common on Earth. Sinkholes, where the ground falls into a hole (sometimes in the middle of a town) resemble pit craters on Mars. However, on the Earth these holes are caused by subsurface limestone being dissolved, thereby causing a void.[22][23][24] The images below of the Cerberus Fossae, the Elysium Fossae and other troughs, as seen by HiRISE are examples of fossae.

Knowledge of the locations and formation mechanisms of pit craters and fossae is important for the future colonization of Mars because they may be reservoirs of water.[25]

-

A trough in the Cerberus Fossae, as seen from THEMIS

-

The Cerberus Fossae, as seen by HiRISE (scale bar is 1.0 km)

-

The Elysium Fossae, as seen by HiRISE (scale bar is 500 m)

-

Troughs to the east of Albor Tholus, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Portion of a trough (fossa) in Elysium, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program (blue indicates probably seasonal frost)[26]

-

Troughs showing layers and dark slope streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Trough, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Close view of layers in trough, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Concentric troughs, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Close view of trough with layers, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Close view of some layers in a trough and a crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

Methane

Methane has been detected in three areas on Mars, one of which is in the Elysium quadrangle.[27] This is exciting because one possible source of methane is from the metabolism of living bacteria.[28] However, a recent study indicates that to match the observations of methane, there must be something that quickly destroys the gas, otherwise it would be spread all through the atmosphere instead of being concentrated in just a few locations. There may be something in the soil that oxidizes the gas before it has a chance to spread. If this is so, that same chemical would destroy organic compounds, thus life would be very difficult on Mars.[29]

Craters

Impact craters generally have a rim with ejecta around them, in contrast volcanic craters usually do not have a rim or ejecta deposits. As craters get larger (greater than 10 km in diameter) they usually have a central peak.[30] The peak is caused by a rebound of the crater floor following the impact.[31] Sometimes craters will display layers. Since the collision that produces a crater is like a powerful explosion, rocks from deep underground are tossed unto the surface. Hence, craters can show us what lies deep under the surface.

Research published in the journal Icarus has found pits in Zunil Crater that are caused by hot ejecta falling on ground containing ice. The pits are formed by heat forming steam that rushes out from groups of pits simultaneously, thereby blowing away from the pit ejecta.[32]

-

Thila Crater, as seen by HiRISE. Picture on right is an enlargement of a part of the other picture. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Mohawk Crater, as seen by HiRISE. Images to the right are enlargements. Far left image shows northern wall, part of crater floor, and the central uplift. Layers in the mantle layer are visible in the far right image.

-

Persbo Crater Wall, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long. Click on image to see details in rock layers in wall.

-

Persbo Crater Floor, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long. Impacts into floor reached a layer of light-toned materials. These materials were then thrown out over a slightly darker surface. Light-toned materials may be hydrated minerals like sulfate.

-

Lockyer Crater Central Hills, as seen by HiRISE

-

Layers in Lockyer Crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Dilly Crater, as seen by HiRISE.

-

Eddie Crater central peak in Elysium quadrangle, as seen by HiRISE

-

Lava flow and crater ejecta, as seen by HiRISE. Impact penetrated into light-toned material then spread it on darker surface. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Crater showing layers and small craters in the ejecta that show a thin ejecta pattern Image taken with HiRISE under HiWish program.

-

West side of Tombaugh, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter)

-

Possible ring-mold craters on floor of large crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Close view of possible ring-mold craters on floor of large crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

-

Crater with a bench, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Craters, layers, and streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of craters that just have ejecta on one side. Image acquired by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Valles in the Elysium quadrangle

Some of the valleys in the Elysium quadrangle seem to start from grabens. Granicus Vallis and Tinjar Vallis begin at a graben that lies just to the west of Elysium Mons. Certain observations suggest that they may have been the location of lahars (mudflows). The graben may have formed because of volcanic dikes. Heat from the dikes would have melted a great deal of ice.[33] Two valley systems, the Hephaestus Fossae and Hebrus Valles, have sections that join and branch at high angles.[34]

The Athabasca Valles are perhaps the youngest outflow channel system on Mars. They lie 620 miles southeast of the large volcano Elysium Mons. Athabasca was formed by water that burst out of the Cerberus Fossae, a set of cracks or fissures in the ground.[35][36] The Cerberus Fossae most likely were formed from the stress on the crust caused by the weight of both Elysium Mons and the Tharsis volcanoes. Current evidence suggests that Cerberus floods probably erupted in several stages.[37] Near the start of these channels (at one of the Cerberus Fossae), the system is called the Athabasca Valles; to the south and east it is called Marte Vallis. Flow rates in Marte Vallis have been estimated at around 100 times that of the Mississippi River. Eventually, the system just seems to fade out in the plains of Amazonis Planitia.[38]

-

Streamlined form in the Athabasca Valles, as seen by HiRISE. Click on image to see layers.

-

Stura Vallis, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Lethe Vallis, as seen by HiRISE. Flow was from southwest to northeast. Wider part of Lethe Vallis had less erosive power, so mesas are left behind from pre-existing material. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Patapsco Vallis, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 1000 meters long.

-

The Rahway Valles, as seen by HiRISE. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Streamlined forms in the Grjota Valles, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Streamlined features, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Layers along streamlines forms, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Streamlined shapes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program These were probably shaped by running water.

-

Streamlined shapes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program These were probably shaped by running water.

-

Small channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Channel network, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Fractured ground

Some places on Mars break up with large fractures that created a terrain with mesas and valleys. Some of these can be quite pretty.

-

Wide view of fractured ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of fractured ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of fractured ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Box shows size of football field. The boulders are the size of houses.

-

Close, color view of fractured ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Surface fractured into mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some of the mesas appear to have moved apart and rotated.

Mesas

Mesas have a flat top and steep sides. Mesas often form from the erosion of a plateau. Mesas represent the remnants of a plateau, so they can show us what types of rocks covered a wide region.[39]

-

Wide view of Buttes and Mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Buttes and mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image.

-

Plateau broken into large blocks, located in Elysium in a large basin called Cerberus Palus. Image taken by HiRISE.

-

Cerberus Palus, as seen by HiRISE

-

Mesas and eroded parts of mesas showing layers and dark slope streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Image is located in eastern Avernus Colles.

-

Spearhead Mesa in Monument Valley. Note the flat top and steep walls that are characteristic of mesas.

More features in the Elysium quadrangle

-

Elysium Mons, as seen with MOLA. Elevations shown by different colors.

-

Rim of Elysium Mons Caldera, as seen by HiRISE. The scale bar is 500 meters long.

-

Wind-blown material darkens areas around a Cerberus Fossae trough. Scale bar for HiRISE image is 500 m.

-

Contact between different surface materials, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program The straight edge may be a fault.

-

Crater with dark slope streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Lava flow and dark slope streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Crater with streaks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

-

Close view of streaks and layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Other Mars quadrangles

Interactive Mars map

Interactive image map of the global topography of Mars. Hover your mouse over the image to see the names of over 60 prominent geographic features, and click to link to them. Coloring of the base map indicates relative elevations, based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor. Whites and browns indicate the highest elevations (+12 to +8 km); followed by pinks and reds (+8 to +3 km); yellow is 0 km; greens and blues are lower elevations (down to −8 km). Axes are latitude and longitude; Polar regions are noted.

Interactive image map of the global topography of Mars. Hover your mouse over the image to see the names of over 60 prominent geographic features, and click to link to them. Coloring of the base map indicates relative elevations, based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor. Whites and browns indicate the highest elevations (+12 to +8 km); followed by pinks and reds (+8 to +3 km); yellow is 0 km; greens and blues are lower elevations (down to −8 km). Axes are latitude and longitude; Polar regions are noted.

See also

References

- ^ Davies, M.E.; Batson, R.M.; Wu, S.S.C. “Geodesy and Cartography” in Kieffer, H.H.; Jakosky, B.M.; Snyder, C.W.; Matthews, M.S., Eds. Mars. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 1992.

- ^ Blunck, J. 1982. Mars and its Satellites. Exposition Press. Smithtown, N.Y.

- ^ a b Cabrol, N. and E. Grin (eds.). 2010. Lakes on Mars. Elsevier. NY.

- ^ Susko, David; Karunatillake, Suniti; Kodikara, Gayantha; Skok, J. R.; Wray, James; Heldmann, Jennifer; Cousin, Agnes; Judice, Taylor (March 2017). "A record of igneous evolution in Elysium, a major martian volcanic province". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 43177. Bibcode:2017NatSR...743177S. doi:10.1038/srep43177. PMC 5324095. PMID 28233797.

- ^ "Mars more Earth-like than moon-like: New Mars research shows evidence of a complex mantle beneath the Elysium volcanic province". ScienceDaily. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Southern Margin of Cerberus Palus (PSP_010744_1840)". Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "NASA.gov". Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ^ Jaeger, W.L.; Keszthelyi, L.P.; Skinner, J.A.; Milazzo, M.P.; McEwen, A.S.; Titus, T.N.; Rosiek, M.R.; Galuszka, D.M.; Howington-Kraus, E.; Kirk, R.L. (January 2010). "Emplacement of the youngest flood lava on Mars: A short, turbulent story". Icarus. 205 (1): 230–243. Bibcode:2010Icar..205..230J. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.09.011.

- ^ Yue, Z., et al. 2017. AN INVESTIGATION OF THE HYPOTHESES FOR FORMATION OF THE PLATY-RIDGEDPOLYGONIZED TERRAIN IN ELYSIUM PLANITIA, MARS. Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017). 1770.pdf

- ^ Keszthelyi, L. et al. 2010. Hydrovolcanic features on Mars: Preliminary observations from the first Mars year of HiRISE. Icarus: 205, 211-229. imaging

- ^ a b "PSR Discoveries: Rootless cones on Mars".

- ^ Lanagan, P., A. McEwen, L. Keszthelyi, and T. Thordarson. 2001. Rootless cones on Mars indicating the presence of shallow equatorial ground ice in recent times, Geophysical Research Letters: 28, 2365-2368.

- ^ S. Fagents1, A., P. Lanagan, R. Greeley. 2002. Rootless cones on Mars: a consequence of lava-ground ice interaction. Geological Society, Londo. Special Publications: 202, 295-317.

- ^ Jaeger, W., L. Keszthelyi, A. McEwen, C. Dundas, P. Russell, and the HiRISE team. 2007. EARLY HiRISE OBSERVATIONS OF RING/MOUND LANDFORMS IN ATHABASCA VALLES, MARS. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVIII 1955.pdf.

- ^ Czechowski, Leszek; Zalewska, Natalia; Zambrowska, Anita; Ciazela, Marta; Witek, Piotr; Kotlarz, Jan (2023). "The formation of cone chains in the Chryse Planitia region on Mars and the thermodynamic aspects of this process". Icarus. 396. Bibcode:2023Icar..39615473C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115473. S2CID 256787389.

- ^ Czechowski, L., et al. 2023. The formation of cone chains in the Chryse Planitia region on Mars and the thermodynamic aspects of this process. Icarus: Volume 396, 15 May 2023, 115473

- ^ "Target Zone: Nilosyrtis? | Mars Odyssey Mission THEMIS".

- ^ "HiRISE | Craters and Valleys in the Elysium Fossae (PSP_004046_2080)".

- ^ "HiRISE | High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment". Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- ^ Skinner, J., L. Skinner, and J. Kargel. 2007. Re-assessment of Hydrovolcanism-based Resurfacing within the Galaxias Fossae Region of Mars. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVIII (2007)

- ^ "HiRISE | Craters and Pit Crater Chains in Chryse Planitia (PSP_008641_2105)".

- ^ a b Wyrick, D., D. Ferrill, D. Sims, and S. Colton. 2003. Distribution, Morphology and Structural Associations of Martian Pit Crater Chains. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIV (2003)

- ^ http://www.swri.edu/4org/d20/DEMPS/planetgeo/planetmars.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mars Global Surveyor MOC2-620 Release".

- ^ Ferrill, D., D. Wyrick, A. Morris, D. Sims, and N. Franklin. 2004. Dilational fault slip and pit chain formation on Mars 14:10:4-12

- ^ "Frosted Gullies in the Northern Summer". HiRISE.

- ^ "Mystery on Mars: Why Methane Fades Away So Fast". Space.com. 20 September 2010.

- ^ Allen, C., D. Oehler, and E. Venechuk. Prospecting for Methane in Arabia Terra, Mars - First Results. Lunar and Planetaary Science XXXVII (2006). 1193.pdf-1193.pdf.

- ^ "Reconciling Methane Variations on Mars".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Stones, Wind, and Ice: A Guide to Martian Impact Craters".

- ^ Hugh H. Kieffer (1992). Mars. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1257-7. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ Tornabene, L. et al. 2012. “Widespread crater-related pitted materials on Mars. Further evidence for the role of target volatiles during the impact process.” Icarus 220: 348-368.

- ^ Christiansen, E. 1989. Lahars in the Elysium region of Mars. Geology. 17: 203-206.

- ^ Michael H. Carr (2006). The surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87201-0. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Cabrol, N. and E. Grin (eds.). 2010. Lakes on Mars. Elsevier. NY

- ^ Burr, D. et al. 2002. Repeated aqueous flooding from the Cerberus Fossae: evidence for very recently extant deep groundwater on Mars. Icarus. 159: 53-73.

- ^ "Feature Image: Floods in Athabasca Valles". Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Hartmann, W. 2003. A Traveler's Guide to Mars. Workman Publishing. NY NY.

- ^ Namowitz, S., D. Stone. earth science The world we live in 1975. American Book Company. New York.

- ^ Morton, Oliver (2002). Mapping Mars: Science, Imagination, and the Birth of a World. New York: Picador USA. p. 98. ISBN 0-312-24551-3.

- ^ "Online Atlas of Mars". Ralphaeschliman.com. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "PIA03467: The MGS MOC Wide Angle Map of Mars". Photojournal. NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. February 16, 2002. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

External links

- Lakes on Mars - Nathalie Cabrol (SETI Talks)

![Rootless Cones, as seen by HiRISE. The chains of rings are interpreted to be caused by crust moving over a source of steam. The steam was produced by lava interacting with water ice.[15] [16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Rootless_Cones.jpg/440px-Rootless_Cones.jpg)

![Portion of a trough (fossa) in Elysium, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program (blue indicates probably seasonal frost)[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/Troughs_showing_blue_in_Elysium_Planitia.JPG/440px-Troughs_showing_blue_in_Elysium_Planitia.JPG)