Dimra

Dimra

دمره Dimrah,[1] Beit Dimreh[2] Demreh[3] | |

|---|---|

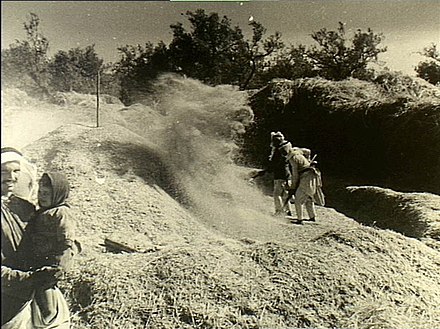

Farmers of Dimra winnowing their corn crop, 1941 | |

| Etymology: Tumrah; personal name. Also called Beit Dimreh, "by the peasantry"[4] | |

A series of historical maps of the area around Dimra (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°33′32″N 34°34′2″E / 31.55889°N 34.56722°E / 31.55889; 34.56722 | |

| Palestine grid | 108/107 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Gaza |

| Date of depopulation | early November 1948[7] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,492 dunams (8.5 km2 or 3.3 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 520[5][6] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Fear of being caught up in the fighting |

| Current Localities | Erez[8] |

Dimra (Arabic: دمره) was a small Arab village located 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) northeast of Gaza City in British Palestine.[2][9] Ancient remains at the site attest to a long-time human settlement there;[citation needed] during the Mamluk era, the town was the home of the Bani Jabir tribe. It was depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and is now the site of Erez, a kibbutz in Israel.

History

Ancient remains found throughout the village, including marble and granite columns as well as pottery, attest to longtime settlement at the site.[2] An excavation have found remains, including coins, dating the sixth century CE, that is the Byzantine empire. Many potsherds, dating to the same period, indicates that a pottery workshop was located there at the time.[10]

Mamluk period

Following the conquest of the Crusader states during the period of Mamluk rule (1270-1516 CE) over Greater Syria (Levant), Dimra was located on an eastward route which left the main Gaza-Jaffa highway at Beit Hanoun.[2] According to Moshe Sharon, Dimra was a likely resting place for those travelling in the region due to its natural, independent water supply.[2]

Three pieces of a marble slab, deposited since 1930 in the Rockefeller Museum, and dated to 676 AH (1277 CE) commemorates the building of a mosque at Dimra at that year.[2][11]

Al-Qalqasandi, an Arab genealogist (d. 1418 CE) noted that Dimra was home to the Bani Jabir, an Arab tribe.[12]

Ottoman period

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the area of Dimra experienced a significant process of settlement decline due to nomadic pressures on local communities. The residents of abandoned villages moved to surviving settlements, but the land continued to be cultivated by neighboring villages.[13]

In 1838, during the Ottoman rule in Palestine, Edward Robinson passed by Dimreh, describing it as located near the bend of a valley.[14] He also noted it as a Muslim village, located in the Gaza district.[1]

In 1863, French explorer Victor Guérin found the village to have 120 inhabitants. He assumed the village had previously been larger, due to several empty houses there. By the well he found one column made of grey granite, and five sections of columns made of grey-white marble. Cucumbers and watermelons were planted in the surrounding gardens.[15] An Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that the village had a population of 198, in a total of 71 houses, though the population count included men, only.[16][17]

In 1883 the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine noted that the place was alternately called Tumrah and Beit Dimreh. The village was small, made of adobe located on the side of a hill. On the north side there was a garden with a water well below it.[18]

British Mandate of Palestine

The village expanded during the British mandate period, and houses were built eastward and southward.[8] In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Dumra had a population of 251, all Muslims,[19] increasing in the 1931 census to 324, still all Muslim, in 100 houses.[20]

In the 1945 statistics Dimra had a population of 520, all Muslims,[5] with a total of 8,492 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey.[6] Of this, 96 dunams were used for citrus and bananas, 388 dunams were for plantations and irrigable land, 7,412 for cereals,[21] while 18 dunams were built-up land.[22] An elementary school opened in Dimra in 1946, with an initial enrollment of 47 students.[8]

1948 War and aftermath

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the women and children of Dimra were reportedly evacuated by the village men on 31 October, likely in response to the advance of the Israeli army.[23]

Following the war the area was incorporated into the State of Israel and kibbutz Erez was founded in 1949 on part of the village site.[8] The remaining structures of the village are described by Khalidi in All That Remains (1992):

"Most of the village is fenced in and used as pasture. A crumbling stone water basin, concrete rubble from houses, and a destroyed well are nearly all that remain. A watering trough for cows has been placed on what appears to be a concrete fragment from a former house. The well is topped with an old, nonoperating water pump. More debris lies in a wooded portion of the site, near a Jewish cemetery. Some cactuses that formerly served as fences, as well as shrubs and thorny plants, grow on adjacent lands.[8]

References

- ^ a b Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 118

- ^ a b c d e f Sharon, 2004, pp. 138-141

- ^ Thomson, 1860, p. 356.

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 363

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 31

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 45

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xix, village #314. Also gives cause of depopulation

- ^ a b c d e Khalidi, 1992, p. 94.

- ^ "Dimra". Palestine Remembered. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Paran, 2007, Erez (East) Final Report

- ^ Mayer, 1933, pp. 32–33

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 94. Quoting Ahmad al-Qalqashandi's Al-Nujum, cited in D1/2:272.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Taxel, Itamar (2023-01-01). "Ḥamāma: The historical geography of settlement continuity and change in Majdal 'Asqalān's hinterland, 1270 - 1750 CE". Journal of Historical Geography. 82: 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2023.08.003.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 2, p. 371. Also cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 94.

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pp. 174-175

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 152 Also noted it in the Gaza district

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 130, also noted 71 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 236

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Gaza, p. 8

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 3.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 86

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 136

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 76

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, C. (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4. (pp. 880–881)

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mayer, L.A. (1933). "Two inscriptions of Baybar". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 2: 32–33.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Paran, Nir Shimshon (2007-10-22). "Erez (East)" (119). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Sharon, M. (2004). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, D-F. Vol. 3. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13197-3.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

External links

- Welcome To Dimra

- Dimra, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 19: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Dimra from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

.jpg/440px-Historical_map_series_for_the_area_of_Dimra_(1870s).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Historical_map_series_for_the_area_of_Dimra_(1940s).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Historical_map_series_for_the_area_of_Dimra_(modern).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Historical_map_series_for_the_area_of_Dimra_(1940s_with_modern_overlay).jpg)