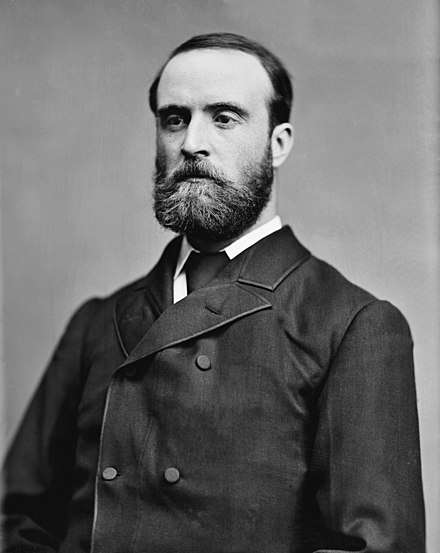

Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party | |

| In office 11 May 1882 – 6 October 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | John Redmond |

| Leader of the Home Rule League | |

| In office 16 April 1880 – 11 May 1882 | |

| Preceded by | William Shaw |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Member of Parliament for Cork City | |

| In office 5 April 1880 – 6 October 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Daniel Murphy |

| Succeeded by | Martin Flavin |

| Member of Parliament for Meath | |

| In office 21 April 1875 – 5 April 1880 | |

| Preceded by | John Martin |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Martin Sullivan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Charles Stewart Parnell 27 June 1846 Avondale, County Wicklow, Ireland |

| Died | 6 October 1891 (aged 45) Hove, East Sussex, England |

| Cause of death | Pneumonia |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, Ireland |

| Political party | Irish Parliamentary Party (1882–1891) Home Rule League (1880–1882) |

| Spouse | |

| Relations |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Magdalene College, Cambridge |

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882, and then of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1882 to 1891, who held the balance of power in the House of Commons during the Home Rule debates of 1885–1886. He fell from power following revelations of a long-term affair, and died at age 45.

Born into a powerful Anglo-Irish Protestant landowning family in County Wicklow, he was a land reform agitator and founder of the Irish National Land League in 1879. He became leader of the Home Rule League, operating independently of the Liberal Party, winning great influence by his balancing of constitutional, radical, and economic issues, and by his skilful use of parliamentary procedure.

He was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, in 1882, but he was released when he renounced violent extra-Parliamentary action. The same year, he reformed the Home Rule League as the Irish Parliamentary Party, which he controlled minutely as Britain's first disciplined democratic party.

The hung parliament of 1885 saw him hold the balance of power between William Gladstone's Liberal Party and Lord Salisbury's Conservative Party. His power was one factor in Gladstone's adoption of Home Rule as the central tenet of the Liberal Party. Parnell's reputation peaked from 1889 to 1890, after letters published in The Times, linking him to the Phoenix Park killings of 1882, were shown to have been forged by Richard Pigott.

The Irish Parliamentary Party split in 1890, following the revelation of Parnell's long adulterous love affair, which led to many British Liberals, many of whom were Nonconformists, refusing to work with him, and engendered strong opposition from Catholic bishops. He headed a small minority faction until his death in 1891.

Parnell's funeral was attended by 200,000, and the day of his death is still remembered as Ivy Day. Parnell Square and Parnell Street in Dublin are named after him, and he is celebrated as the best organiser of an Irish political party up to that time, and one of the most formidable figures in parliamentary history.

Early life

Charles Stewart Parnell[a] was born in Avondale House, County Wicklow. He was the third son and seventh child of John Henry Parnell (1811–1859), a wealthy Anglo-Irish Anglican landowner, and his American wife Delia Tudor Stewart (1816–1898) of Bordentown, New Jersey, daughter of the American naval hero Admiral Charles Stewart (the stepson of one of George Washington's bodyguards). There were eleven children in all: five boys and six girls. Admiral Stewart's mother, Parnell's great-grandmother, belonged to the Tudor family, so Parnell had a distant relationship with the British royal family. John Henry Parnell himself was a cousin of one of Ireland's leading aristocrats, Viscount Powerscourt, and also the grandson of a Chancellor of the Exchequer in Grattan's Parliament, Sir John Parnell, who lost office in 1799, when he opposed the Act of Union.[1]

The Parnells of Avondale were descended from a Protestant English merchant family, which came to prominence in Congleton, Cheshire, early in the 17th century where two generations held the office of Mayor of Congleton before moving to Ireland.[2] The family produced a number of notable figures, including Thomas Parnell (1679–1718), the Irish poet, and Henry Parnell, 1st Baron Congleton (1776–1842), the Irish politician. Parnell's grandfather William Parnell (1780–1821), who inherited the Avondale Estate in 1795, was an Irish liberal Party MP for Wicklow from 1817 to 1820. Thus, from birth, Charles Stewart Parnell possessed an extraordinary number of links to many elements of society; he was linked to the old Irish Parliamentary tradition via his great-grandfather and grandfather, to the American War of Independence via his grandfather, to the War of 1812 (where his grandfather Charles Stewart (1778–1869) had been awarded a gold medal by the United States Congress for gallantry in the U.S. Navy). Parnell belonged to the Church of Ireland, disestablished in 1868 (its members mostly unionists) though in later years he began to drop away from formal church attendance;[1] and he was connected with the aristocracy through the Powerscourts. Yet it was as a leader of Irish Nationalism that Parnell established his fame.

Parnell's parents separated when he was six, and as a boy, he was sent to different schools in England, where he spent an unhappy youth. His father died in 1859 and he inherited the Avondale estate, while his older brother John inherited another estate in County Armagh. The young Parnell studied at Magdalene College, Cambridge (1865–69) but, due to the troubled financial circumstances of the estate he inherited, he was absent a great deal and never completed his degree. In 1871, he joined his elder brother John Howard Parnell (1843–1923), who farmed in Alabama (later an Irish Parnellite MP and heir to the Avondale estate), on an extended tour of the United States. Their travels took them mostly through the South and apparently, the brothers neither spent much time in centres of Irish immigration nor sought out Irish-Americans.

In 1874, he became High Sheriff of Wicklow, his home county in which he was also an officer in the Wicklow militia. He was noted as an improving landowner who played an important part in opening the south Wicklow area to industrialisation.[1] His attention was drawn to the theme dominating the Irish political scene of the mid-1870s, Isaac Butt's Home Rule League formed in 1873 to campaign for a moderate degree of self-government. It was in support of this movement that Parnell first tried to stand for election in Wicklow, but as high sheriff was disqualified. He was unsuccessful as a home rule candidate in the 1874 County Dublin by-election.

Rise to political power

On 17 April 1875, Parnell was first elected to the House of Commons in a by-election for Meath, as a Home Rule League MP, backed by Fenian Patrick Egan.[1] He replaced the deceased League MP, veteran Young Irelander John Martin. Parnell later sat for the constituency of Cork City, from 1880 until 1891.

During his first year as an MP, Parnell remained a reserved observer of parliamentary proceedings. He first came to attention in the public eye in 1876, when he claimed in the House of Commons that he did not believe that any murder had been committed by Fenians in Manchester. That drew the interest of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a physical force Irish organisation that had staged a rebellion in 1867.[3] Parnell made it his business to cultivate Fenian sentiments both in Britain and Ireland[1] and became associated with the more radical wing of the Home Rule League, which included Joseph Biggar (MP for Cavan from 1874), John O'Connor Power (MP for County Mayo from 1874) (both, although constitutionalists, had links with the IRB), Edmund Dwyer-Gray (MP for Tipperary from 1877), and Frank Hugh O'Donnell (MP for Dungarvan from 1877). He engaged with them and played a leading role in a policy of obstructionism[1] (i.e., the use of technical procedures to disrupt the House of Commons ability to function) to force the House to pay more attention to Irish issues, which had previously been ignored. Obstruction involved giving lengthy speeches which were largely irrelevant to the topic at hand. This behaviour was opposed by the less aggressive chairman (leader) of the Home Rule League, Isaac Butt.

Parnell visited the United States that year, accompanied by O'Connor Power. The question of Parnell's closeness to the IRB, and whether indeed he ever joined the organisation, has been a matter of academic debate for a century. The evidence suggests that later, following the signing of the Kilmainham Treaty, Parnell did take the IRB oath, possibly for tactical reasons.[4] What is known is that IRB involvement in the League's sister organisation, the Home Rule Confederation of Great Britain, led to the moderate Butt's ousting from its presidency (even though he had founded the organisation) and the election of Parnell in his place, on 28 August 1877.[5] Parnell was a restrained speaker in the House of Commons, but his organisational, analytical and tactical skills earned wide praise, enabling him to take on the presidency of the British organisation. Butt died in 1879, and was replaced as chairman of the Home Rule League by the Whig-oriented William Shaw. Shaw's victory was only temporary.

New departure

From August 1877, Parnell held a number of private meetings with prominent Fenian leaders. He visited Paris where he met John O'Leary and J. J. O'Kelly both of whom were impressed by him and reported positively to the most capable and militant Leader of the American republican Clan na Gael organisation, John Devoy.[1][3] In December 1877, at a reception for Michael Davitt on his release from prison, he met William Carrol who assured him of Clan na Gael's support in the struggle for Irish self-government. This led to a meeting in March 1878 between influential constitutionalists, Parnell and Frank Hugh O'Donnell, and leading Fenians O'Kelly, O'Leary and Carroll. This was followed by a telegram from John Devoy in October 1878 which offered Parnell a "New Departure" deal of separating militancy from the constitutional movement as a path to all-Ireland self-government, under certain conditions: abandonment of a federal solution in favour of separatist self-government, vigorous agitation in the land question on the basis of peasant proprietorship, exclusion of all sectarian issues, collective voting by party members and energetic resistance to coercive legislation.[1][3]

Parnell preferred to keep all options open without clearly committing himself when he spoke in 1879 before Irish Tenant Defence Associations at Ballinasloe and Tralee. It was not until Davitt persuaded him to address a second meeting at Westport, County Mayo in June that he began to grasp the potential of the land reform movement. At a national level, several approaches were made which eventually produced the "New Departure" of June 1879, endorsing the foregone informal agreement which asserted an understanding binding them to mutual support and a shared political agenda. In addition, the New Departure endorsed the Fenian movement and its armed strategies.[6] Working together with Davitt (who was impressed by Parnell[7]) he now took on the role of leader of the New Departure, holding platform meeting after platform meeting around the country.[3] Throughout the autumn of 1879, he repeated the message to tenants, after the long depression had left them without income for rent:

You must show the landlord that you intend to keep a firm grip on your homesteads and lands. You must not allow yourselves be dispossessed as you were dispossessed in 1847.

— Collins 2008, p. 47

Land League leader

Parnell was elected president of Davitt's newly founded Irish National Land League in Dublin on 21 October 1879, signing a militant Land League address campaigning for land reform. In so doing, he linked the mass movement to the parliamentary agitation, with profound consequences for both of them. Andrew Kettle, his 'right-hand man', became honorary secretary.

In a bout of activity, he left for America in December 1879 with John Dillon to raise funds for famine relief and secure support for Home Rule. Timothy Healy followed to cope with the press and they collected £70,000[3] for distress in Ireland. During Parnell's highly successful tour, he had an audience with American President Rutherford B. Hayes. On 2 February 1880, he addressed the United States House of Representatives on the state of Ireland and spoke in 62 cities in the United States and in Canada. He was so well received in Toronto that Healy dubbed him "the uncrowned king of Ireland".[3] (The same term was applied 30 years earlier to Daniel O'Connell.) He strove to retain Fenian support but insisted when asked by a reporter that he personally could not join a secret society.[1] Central to his whole approach to politics was ambiguity in that he allowed his hearers to remain uncertain. During his tour, he seemed to be saying that there were virtually no limits. To abolish landlordism, he asserted, would be to undermine English misgovernment, and he is alleged to have added:

When we have undermined English misgovernment we have paved the way for Ireland to take her place amongst the nations of the earth. And let us not forget that that is the ultimate goal at which all we Irishmen aim. None of us whether we be in America or in Ireland ... will be satisfied until we have destroyed the last link which keeps Ireland bound to England.

— Lyons 1973, p. 186

His activities came to an abrupt end when the 1880 United Kingdom general election was announced for April and he returned to fight it. The Conservatives were defeated by the Liberal Party; William Gladstone was again Prime Minister. Sixty-three Home Rulers were elected, including twenty-seven Parnell supporters, Parnell being returned for three seats: Cork City, Mayo and Meath. He chose to sit for the Cork seat. His triumph facilitated his nomination in May in place of Shaw as leader of a new Home Rule League Party, faced with a country on the brink of a land war.

Although the League discouraged violence, agrarian outrages grew from 863 incidents in 1879 to 2,590 in 1880[1] after evictions increased from 1,238 to 2,110 in the same period. Parnell saw the need to replace violent agitation with country-wide mass meetings and the application of Davitt's boycott, also as a means of achieving his objective of self-government. Gladstone was alarmed at the power of the Land League at the end of 1880.[8] He attempted to defuse the land question with dual ownership in the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881, establishing a Land Commission that reduced rents and enabled some tenants to buy their farms. These halted arbitrary evictions, but not where rent was unpaid.

Historian R. F. Foster argues that in the countryside the Land League "reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and—implicitly—Protestantism."[9]

Kilmainham Treaty

Parnell's own newspaper, the United Ireland, attacked the Land Act[3] and he was arrested on 13 October 1881, together with his party lieutenants, William O'Brien, John Dillon, Michael Davitt and Willie Redmond, who had also conducted a bitter verbal offensive. They were imprisoned under a proclaimed Coercion Act in Kilmainham Gaol for "sabotaging the Land Act", from where the No Rent Manifesto, which Parnell and the others signed, was issued calling for a national tenant farmer rent strike. The Land League was suppressed immediately.

_Irish_Frankenstein.jpg/440px-Punch_Anti-Irish_propaganda_(1882)_Irish_Frankenstein.jpg)

Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a deal with the government, negotiated through Captain William O'Shea MP, that, provided the government settled the "rent arrears" question allowing 100,000 tenants to appeal for fair rent before the land courts, then withdrawing the manifesto and undertaking to move against agrarian crime, after he realised militancy would never win Home Rule. Parnell also promised to use his good offices to quell the violence and to cooperate cordially for the future with the Liberal Party in forwarding Liberal principles and measures of general reform.[10]

His release on 2 May, following the so-called Kilmainham Treaty, marked a critical turning point in the development of Parnell's leadership when he returned to the parameters of parliamentary and constitutional politics,[11] and resulted in the loss of support of Devoy's American-Irish. His political diplomacy preserved the national Home Rule movement after the Phoenix Park killings of the Chief Secretary Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his Under-Secretary, T. H. Burke on 6 May. Parnell was shocked to the extent that he offered Gladstone to resign his seat as MP.[1] The militant Invincibles responsible fled to the United States, which allowed him to break links with radical Land Leaguers. In the end, it resulted in a Parnell – Gladstone alliance working closely together. Davitt and other prominent members left the IRB, and many rank-and-file Fenians drifted into the Home Rule movement. For the next 20 years, the IRB ceased to be an important force in Irish politics,[12] leaving Parnell and his party the leaders of the nationalist movement in Ireland.[12]

Party restructured

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

,_199_-_BL.jpg/440px-The_Irish_Vampire_-_Punch_(24_October_1885),_199_-_BL.jpg)

Parnell now sought to use his experience and huge support to advance his pursuit of Home Rule and resurrected the suppressed Land League, on 17 October 1882, as the Irish National League (INL). It combined moderate agrarianism, a Home Rule programme with electoral functions, was hierarchical and autocratic in structure with Parnell wielding immense authority and direct parliamentary control.[13] Parliamentary constitutionalism was the future path.

The informal alliance between the new, tightly disciplined INL and the Catholic Church was one of the main factors for the revitalisation of the national Home Rule cause after 1882. Parnell saw that the explicit endorsement of Catholicism was of vital importance to the success of this venture and worked in close cooperation with the Catholic hierarchy in consolidating its hold over the Irish electorate.[14] The leaders of the Catholic Church largely recognised the Parnellite party as guardians of church interests, despite uneasiness with a powerful lay leadership.[15]

At the end of 1885, the highly centralised organisation had 1,200 branches spread around the country, though there were fewer in Ulster than in the other provinces.[16] Parnell left the day-to-day running of the INL in the hands of his lieutenants Timothy Harrington as Secretary, William O'Brien, editor of its newspaper United Ireland, and Tim Healy. Its continued agrarian agitation led to the passing of several Irish Land Acts that over three decades changed the face of Irish land ownership, replacing large Anglo-Irish estates with tenant ownership.

Parnell next turned to the Home Rule League Party, of which he was to remain the re-elected leader for over a decade, spending most of his time at Westminster, with Henry Campbell as his personal secretary. He fundamentally changed the party, replicated the INL structure within it and created a well-organised grassroots structure, introduced membership to replace "ad hoc" informal groupings in which MPs with little commitment to the party voted differently on issues, often against their own party.[b] Some did not attend the House of Commons at all, citing expense, given that MPs were unpaid until 1911 and the journey to Westminster was both costly and arduous.

In 1882, he changed his party's name to the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). A central aspect of Parnell's reforms was a new selection procedure to ensure the professional selection of party candidates committed to taking their seats. In 1884, he imposed a firm 'party pledge' which obliged party MPs to vote as a bloc in parliament on all occasions. The creation of a strict party whip and formal party structure was unique in party politics at the time. The Irish Parliamentary Party is generally seen as the first modern British political party, its efficient structure and control contrasting with the loose rules and flexible informality found in the main British parties, which came to model themselves on the Parnellite model. The Representation of the People Act 1884 enlarged the franchise, and the IPP increased its number of MPs from 63 to 85 in the 1885 election.

The changes affected the nature of candidates chosen. Under Butt, the party's MPs were a mixture of Catholic and Protestant, landlord and others, Whig, Liberal and Conservative, often leading to disagreements in policy that meant that MPs split in votes. Under Parnell, the number of Protestant and landlord MPs dwindled, as did the number of Conservatives seeking election. The parliamentary party became much more Catholic and middle class, with a large number of journalists and lawyers elected and the disappearance of Protestant Ascendancy landowners and Conservatives from it.

Push for home rule

Parnell's party emerged swiftly as a tightly disciplined and, on the whole, energetic body of parliamentarians.[14] By 1885, he was leading a party well-poised for the next general election, his statements on Home Rule designed to secure the widest possible support. Speaking in Cork on 21 January 1885, he stated:

We cannot ask the British constitution for more than the restitution of Grattan's parliament, but no man has the right to fix the boundary of a nation. No man has the right to say to his country, "Thus far shalt thou go and no further", and we have never attempted to fix the "ne plus ultra" to the progress of Ireland's nationhood, and we never shall.

— Hickey & Doherty 2003, pp. 382–385

Both British parties toyed with various suggestions for greater self-government for Ireland. In March 1885, the British cabinet rejected the proposal of radical minister Joseph Chamberlain of democratic county councils which in turn would elect a Central Board for Ireland. Gladstone on the other hand said he was prepared to go 'rather further' than the idea of a Central Board.[17] After the collapse of Gladstone's government in June 1885, Parnell urged the Irish voters in Britain to vote against the Liberal Party. The November general elections (delayed because boundaries were being redrawn and new registers prepared after the Third Reform Act) brought about a hung Parliament in which the Liberals with 335 seats won 86 more than the Conservatives, with a Parnellite bloc of 86 Irish Home Rule MPs holding the balance of power in the Commons. Parnell's task was now to win acceptance of the principle of a Dublin parliament.

Parnell at first supported a Conservative government – they were still the smaller party after the elections – but after renewed agrarian distress arose when agricultural prices fell and unrest developed during 1885, Lord Salisbury's Conservative government announced coercion measures in January 1886. Parnell switched his support to the Liberals.[3] The prospects shocked Unionists. The Orange Order, revived in the 1880s to oppose the Land League, now openly opposed Home Rule. On 20 January, the Irish Unionist Party was established in Dublin.[18] By 28 January, Salisbury's government had resigned.

The Liberal Party regained power on 1 February, their leader Gladstone – influenced by the status of Norway, which at the time was self-governing but under the Swedish Crown – moving towards Home Rule, which Gladstone's son Herbert revealed publicly under what became known as the "flying of the Hawarden Kite". The third Gladstone administration paved the way towards the generous response to Irish demands that the new Prime Minister had promised,[19] but was unable to obtain the support of several key players in his own party. Lord Hartington (who had been Liberal leader in the late 1870s and was still the most likely alternative leader) refused to serve at all, while Joseph Chamberlain briefly held office then resigned when he saw the terms of the proposed bill.

On 8 April 1886, Gladstone introduced the First Irish Home Rule Bill, his object to establish an Irish legislature, although large imperial issues were to be reserved to the Westminster parliament.[1] The Conservatives now emerged as enthusiastic unionists, Lord Randolph Churchill declared, "The Orange card is the one to play".[20] In the course of a long and fierce debate Gladstone made a remarkable Home Rule Speech, beseeching parliament to pass the bill. However, the split between pro- and anti-home rulers within the Liberal Party caused the defeat of the bill on its second reading in June by 341 to 311 votes.[21]

Parliament was dissolved and elections called, with Irish Home Rule the central issue. Gladstone hoped to repeat his triumph of 1868, when he fought and won a general election to obtain a mandate for Irish Disestablishment (which had been a major cause of dispute between Conservatives and Liberals since the 1830s), but the result of the July 1886 general election was a Liberal defeat. The Conservatives and the Liberal Unionist Party returned with a majority of 118 over the combined Gladstonian Liberals and Parnell's 85 Irish Party seats. Salisbury formed his second government – a minority Conservative government with Liberal Unionist support.

The Liberal split made the Unionists (the Liberal Unionists sat in coalition with the Conservatives after 1895 and would eventually merge with them) the dominant force in British politics until 1906, with strong support in Lancashire, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham (the fiefdom of its former mayor Joseph Chamberlain who as recently as 1885 had been a furious enemy of the Conservatives) and the House of Lords where many Whigs sat (a second Home Rule Bill would pass the Commons in 1893 only to be overwhelmingly defeated in the Lords).

Pigott forgeries

Parnell next became the centre of public attention when in March and April 1887 he found himself accused by the British newspaper The Times of supporting the brutal murders in May 1882 of the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and the Permanent Under-Secretary, Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin's Phoenix Park, and of the general involvement of his movement with crime (i.e., with illegal organisations such as the IRB). Letters were published which suggested Parnell was complicit in the murders. The most important one, dated 15 May 1882, ran as follows:

Dear Sir, – I am not surprised at your friend's anger, but he and you should know that to denounce the murders was the only course open to us. To do that promptly was plainly our best policy. But you can tell him, and all others concerned, that, though I regret the accident of Lord Frederick Cavendish's death, I cannot refuse to admit that Burke got no more than his deserts. You are at liberty to show him this, and others whom you can trust also, but let not my address be known. He can write to House of Commons.

Yours very truly,

Chas S. Parnell.

— Special Commission 1890, p. 58

A Commission of Enquiry, which Parnell had requested, revealed in February 1889, after 128 sessions that the letters were a fabrication created by Richard Pigott, a disreputable anti-Parnellite rogue journalist. Pigott broke down under cross-examination after the letter was shown to be a forgery by him with his characteristic spelling mistakes. He fled to Madrid where he committed suicide. Parnell was vindicated, to the disappointment of the Tories and the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury.[22]

The 35-volume commission report published in February 1890, did not clear Parnell's movement of criminal involvement. Parnell then took The Times to court and the newspaper paid him £5,000 (equivalent to £585,000 in 2021) damages in an out-of-court settlement. When Parnell entered the House of Commons on 1 March 1890, after he was cleared, he received a hero's reception from his fellow MPs led by Gladstone.[3] It had been a dangerous crisis in his career, yet Parnell had at all times remained calm, relaxed and unperturbed which greatly impressed his political friends. But while he was vindicated in triumph, links between the Home Rule movement and militancy had been established. This he could have survived politically were it not for the crisis to follow.

Pinnacle of power

During the period 1886–90, Parnell continued to pursue Home Rule, striving to reassure British voters that it would be no threat to them. In Ireland, unionist resistance (especially after the Irish Unionist Party was formed) became increasingly organised.[1] Parnell pursued moderate and conciliatory tenant land purchase and still hoped to retain a sizeable landlord support for home rule. During the agrarian crisis, which intensified in 1886 and launched the Plan of Campaign organised by Parnell's lieutenants, he chose in the interest of Home Rule not to associate himself with it.[1]

All that remained, it seemed, was to work out details of a new home rule bill with Gladstone. They held two meetings, one in March 1888 and a second more significant meeting at Gladstone's home in Hawarden on 18–19 December 1889. On each occasion, Parnell's demands were entirely within the accepted parameters of Liberal thinking, Gladstone noting that he was one of the best people he had known to deal with,[1] a remarkable transition from an inmate at Kilmainham to an intimate at Hawarden in just over seven years.[23] This was the high point of Parnell's career. In the early part of 1890, he still hoped to advance the situation on the land question, with which a substantial section of his party was displeased.

Political downfall

Divorce crisis

Parnell's leadership was first put to the test in February 1886, when he forced the candidature of Captain William O'Shea, who had negotiated the Kilmainham Treaty, for a Galway by-election. Parnell rode roughshod over his lieutenants Healy, Dillon and O'Brien who were not in favour of O'Shea. Galway was the harbinger of the fatal crisis to come.[1] O'Shea had separated from his wife Katharine O'Shea, sometime around 1875,[24] but would not divorce her as she was expecting a substantial inheritance. Mrs. O'Shea acted as liaison in 1885 with Gladstone during proposals for the First Home Rule Bill.[25][26] Parnell later took up residence with her in Eltham, Kent, in the summer of 1886,[3] and was a known overnight visitor at the O'Shea house in Brockley, Kent.[27][28][29] When Mrs O'Shea's aunt died in 1889, her money was left in trust.

On 24 December 1889, Captain O'Shea filed for divorce, citing Parnell as co-respondent, although the case did not come to trial until 15 November 1890. The two-day trial revealed that Parnell had been the long-term lover of Mrs. O'Shea and had fathered three of her children. Meanwhile, Parnell assured the Irish Party that there was no need to fear the verdict because he would be exonerated. During January 1890, resolutions of confidence in his leadership were passed throughout the country.[3] Parnell did not contest the divorce action at a hearing on 15 November, to ensure that it would be granted and he could marry Mrs O'Shea, so Captain O'Shea's allegations went unchallenged. A divorce decree was granted on 17 November 1890, but Parnell's two surviving children were placed in O'Shea's custody.

News of the long-standing adultery created a huge public scandal. The Irish National League passed a resolution to confirm his leadership. The Catholic Church hierarchy in Ireland was shocked by Parnell's immorality and feared that he would wreck the cause of Home Rule. Besides the issue of tolerating immorality, the bishops sought to keep control of Irish Catholic politics, and they no longer trusted Parnell as an ally. The chief Catholic leader, Archbishop Walsh of Dublin, came under heavy pressure from politicians, his fellow bishops, and Cardinal Manning; Walsh finally declared against Parnell. Larkin 1961 says, "For the first time in Irish history, the two dominant forces of Nationalism and Catholicism came to a parting of the ways.

In England one strong base of Liberal Party support was Nonconformist Protestantism, such as the Methodists; the 'nonconformist conscience' rebelled against having an adulterer play a major role in the Liberal Party.[30] Gladstone warned that if Parnell retained the leadership, it would mean the loss of the next election, the end of their alliance, and also of Home Rule. With Parnell obdurate, the alliance collapsed in bitterness.[31]

Party divides

When the annual party leadership election was held on 25 November, Gladstone's threat was not conveyed to the members until after they had loyally re-elected their 'chief' in his office.[1][3] Gladstone published his warning in a letter the next day; angry members demanded a new meeting, and this was called for 1 December. Parnell issued a manifesto on 29 November, saying a section of the party had lost its independence; he falsified Gladstone's terms for Home Rule and said they were inadequate. A total of 73 members were present for the fateful meeting in committee room 15 at Westminster. Leaders tried desperately to achieve a compromise in which Parnell would temporarily withdraw. Parnell refused. He vehemently insisted that the independence of the Irish party could not be compromised either by Gladstone or by the Catholic hierarchy.[1] As chairman, he blocked any motion to remove him.

On 6 December, after five days of vehement debate, a majority of 44 present led by Justin McCarthy walked out to found a new organisation, thus creating rival Parnellite and anti-Parnellite parties. The minority of 28 who remained true to their embattled 'Chief' continued in the Irish National League under John Redmond, but all of his former close associates, Michael Davitt, John Dillon, William O'Brien and Timothy Healy deserted him to join the anti-Parnellites. The vast majority of anti-Parnellites formed the Irish National Federation, later led by John Dillon and supported by the Catholic Church. The bitterness of the split tore Ireland apart and resonated well into the next century. Parnell soon died, and his faction dissipated. The majority faction henceforth played only a minor role in British or Irish politics until the next time the UK had a hung Parliament, in 1910.[32]

Undaunted defiance

Parnell fought back desperately, despite his failing health. On 10 December, he arrived in Dublin to a hero's welcome.[1] He and his followers forcibly seized the offices of the party paper United Irishman. A year before, his prestige had reached new heights, but the new crisis crippled this support, and most rural nationalists turned against him. In the December North Kilkenny by-election, he attracted Fenian "hillside men" to his side. This ambiguity shocked former adherents, who clashed physically with his supporters; his candidate lost by almost two to one.[3] Deposed as leader, he fought a long and fierce campaign for reinstatement. He conducted a political tour of Ireland to re-establish popular support. In a North Sligo by-election, the defeat of his candidate by 2,493 votes to 3,261 was less resounding.[3]

He fulfilled his loyalty to Katharine when they married on 25 June 1891, after Parnell had unsuccessfully sought a church wedding. On the same day, the Irish Catholic hierarchy, worried by the number of priests who had supported him in North Sligo, signed and published a near-unanimous condemnation: "by his public misconduct, has utterly disqualified himself to be ... leader."[33] Only Edward O'Dwyer, bishop of Limerick withheld his signature. The Parnells took up residence in Brighton.

He returned to fight the third and last by-election in County Carlow, having lost the support of the Freeman's Journal when its proprietor Edmund Dwyer-Gray defected to the anti-Parnellites. At one point quicklime was thrown at his eyes by a hostile crowd in Castlecomer, County Kilkenny. Parnell continued the exhausting campaigning. One loss followed another but he looked to the next general election in 1892 to restore his fortunes. On 27 September, he addressed a crowd in pouring rain at Creggs, subjecting himself to a severe soaking. On the difficult campaign trail, his health continuously deteriorated; furthermore, he had kidney disease. Parnell fought on furiously but, though aged just 45, he was a dying man.[34]

Death and legacy

.jpg/440px-Cemetery-_Parnell's_Grave-_Glasnevin_Co._Dublin_(19257693464).jpg)

He returned to Dublin on 30 September. He died in his home at 10 Walsingham Terrace, Hove (now replaced by Dorset Court, Kingsway) on 6 October 1891 of pneumonia and in the arms of his wife Katharine.[1] He was 45 years of age at the time of his death. Though an Anglican, his funeral on 11 October was at the Irish National nondenominational Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, and was attended by more than 200,000 people.[3] His notability was such that his gravestone of unhewn Wicklow granite, erected in 1940,[35] reads only "Parnell".

His brother John Howard inherited the Avondale estate. He found it heavily mortgaged and eventually sold it in 1899. Five years later, at the suggestion of Horace Plunkett, it was purchased by the state. It is open to public view and is where the "Parnell Society" holds its annual August summer school. The "Parnell National Memorial Park" is in nearby Rathdrum, County Wicklow. Dublin has locations named Parnell Street and Parnell Square. At the north end of O'Connell Street stands the Parnell Monument. This was planned and organised by John Redmond, who chose the American Augustus Saint Gaudens to sculpt the statue; it was funded by Americans and completed in 1911. Art critics said it was not an artistic success.[36]

He is also commemorated on the first Sunday after the anniversary of his death on 6 October, known as Ivy Day, which originated when the mourners at his funeral in 1891, taking their cue from a wreath of ivy sent by a Cork woman "as the best offering she could afford", took ivy leaves from the walls and stuck them in their lapels. Ever after, the ivy leaf became the Parnellite emblem, worn by his followers when they gathered to honour their lost leader.[37]

Marie Owens named her firstborn son after him.[38]

Since 1991, the centenary of his death, Magdalene College, Cambridge, where Parnell studied, has offered the Parnell Fellowship in Irish Studies, which is awarded to a scholar for up to a year for study without teaching or administrative responsibilities. Parnell Fellows have often been historians, but have spanned a wide range of disciplines.

Political views and affiliations

Parnell's personal political views remained an enigma. An effective communicator, he was skilfully ambivalent and matched his words depending on circumstances and audience, but he would always first defend constitutionalism on which basis he sought to bring about change, but he was hampered by the crimes that hung around the Land League and by the opposition of landlords against the attacks on their property.[1]

Parnell's personal complexities or his perception of a need for political expediency to his goal permitted him to condone the radical republican and atheist Charles Bradlaugh, while he associated himself with the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. Parnell was a close friend and political associate of fellow land reform activist Thomas Nulty, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Meath, until Parnell's divorce crisis in 1889.[39][40]

Parnell was linked both with the landed aristocracy class and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), with speculation in the 1890s that he may have even joined the latter organisation. Historian Andrew Roberts argues that he was sworn into the IRB in the Old Library at Trinity College Dublin in May 1882 and that this was concealed for 40 years.[c] In Barry O'Brien's Parnell, X, Fenian Parliamentarian John O'Connor Power, relates, 'And, in fact, I was, about this time [1877], deputed to ask Parnell to join us. I did ask him. He said "No" without a moment's hesitation.'[42]

Parnell was conservative by nature, which leads some historians to suggest that personally, he would have been closer to the Conservative Party, rather than the Liberal Party, but for political needs. Andrew Kettle, Parnell's right-hand man, who shared many of his opinions, wrote of his own views, "I confess that I felt [in 1885], and still feel, a greater leaning towards the British Tory party than I ever could have towards the so-called Liberals".[43] In later years, the double effect of the Phoenix Park trauma and the O'Shea affair reinforced the conservative side of his nature.[1]

Legacy

Charles Stewart Parnell possessed the remarkable attribute of charisma, was an enigmatic personality and politically gifted, and is regarded as one of the most extraordinary figures in Irish and British politics. He played a part in the process that undermined his own Anglo-Irish caste; within two decades absentee landlords were almost unknown in Ireland. He created single-handedly in the Irish Party Britain's first modern, disciplined, political-party machine. He held all the reins of Irish nationalism and also harnessed Irish-America to finance the cause. He played an important role in the rise and fall of British governments in the mid-1880s and in Gladstone's conversion to Irish Home Rule.[44]

Over a century after his death he is still surrounded by public interest. His death, and the divorce upheaval which preceded it, gave him a public appeal and interest that other contemporaries, such as Timothy Healy or John Dillon, could not match. His leading biographer, F. S. L. Lyons, says historians emphasise numerous major achievements: Above all there is the emphasis on constitutional action, as historians point to the Land Act of 1881; the creation of the powerful third force in Parliament using a highly disciplined party that he controlled; the inclusion of Ireland in the Reform Act of 1884, while preventing any reduction in the number of Irish seats; the powerful role of the Irish National League and organising locally, especially County conventions that taught peasants about democratic self-government; forcing Home Rule to be a central issue in British politics; and persuading the great majority of the Liberal party to adopt his cause. Lyons agrees that these were remarkable achievements, but emphasises that Parnell did not accomplish them alone, but only in close coordination with men such as Gladstone and Davitt.[45]

Gladstone described him: "Parnell was the most remarkable man I ever met. I do not say the ablest man; I say the most remarkable and the most interesting. He was an intellectual phenomenon."[46] Liberal leader H. H. Asquith called him one of the three or four greatest men of the 19th century, while Lord Haldane described him as the strongest man the House of Commons had seen in 150 years. Historian A. J. P. Taylor says, "More than any other man he gave Ireland the sense of being an independent nation."[47]

Lyons points up the dark side as well. The decade-long liaison with Mrs. O'Shea was a disaster waiting to happen, and Parnell had made no preparations for it. He waited so long because of money – there was an expectation that Mrs. O'Shea would receive a large inheritance from her elderly aunt who might have changed her will if she had known about the affair.[d] In the aftermath of the divorce he fought violently to retain control in a hopeless cause. Thereby he ruined his health and wrecked his movement, which never fully recovered. The bottom line for Lyons, however, is positive:

He gave his people back their self respect. He did this ... by rallying an inert and submissive peasantry to believe that by organized and disciplined protest they could win a better life for themselves and their children. He did it further, and still more strikingly, by demonstrating ... that even a small Irish party could disrupt the business of the greatest legislature in the world and, by a combination of skill and tenacity, could deal on equal terms with – eventually, hold the balance between – the two major English parties.

— Lyons 1973, p. 616

Portrayal in fiction

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

In Knut Hamsun's 1892 novel Mysteries, the characters, on a couple of occasions, briefly discuss Charles Stewart Parnell, particularly in relation to Gladstone: "Dr. Stenerson had a high opinion of Parnell, but if Gladstone was so opposed to him, he must know what he was about—with apologies to the host, Mr. Nagel, who couldn't forgive Gladstone for being an honourable man".

Parnell's death shocks the character Eleanor in Virginia Woolf's novel The Years, published in 1937: "... how could he be dead? It was like something fading in the sky."

Parnell is toasted in the 1938 poem of William Butler Yeats, "Come Gather Round Me, Parnellites", while he is also referred to in "To a Shade", where he performs the famous "C.S.Parnell Style", and in Yeats' two-line poem "Parnell".

In W. Somerset Maugham's The Razor's Edge, published in 1944, the author mentions Parnell and O'Shea: "Passion is destructive. It destroyed Antony and Cleopatra, Tristan and Isolde, Parnell and Kitty O'Shea."

Parnell is the subject of a discussion in Irish author James Joyce's first chapter of the semi-autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, first serialised in The Egoist magazine in 1914–15. Parnell appears in "Ivy Day in the Committee Room" in Dubliners. He is also discussed in Ulysses, as is his brother.[49] The main character in Finnegans Wake, HCE, is partially based on Parnell;[e] among other resemblances, both are accused of transgressions in Phoenix Park.

Parnell is a major background character in Thomas Flanagan's 1988 historical novel The Tenants of Time, and in Leon Uris's 1976 historical novel Trinity.

Parnell was played by Clark Gable in Parnell, the 1937 MGM production about the Irish leader. Instead of wearing a full beard like the real Parnell, the popular actor sported sideburns in addition to his trademark moustache. The film is notable as Gable's biggest flop and occurred at the height of his career when almost every Gable film was a smash hit. Parnell was portrayed by Robert Donat in the 1947 film Captain Boycott. In 1954, Patrick McGoohan played Parnell in "The Fall of Parnell (December 6, 1890)", an episode of the historical television series You Are There.

In 1991, Trevor Eve played Parnell in the television mini-series Parnell and the Englishwoman.

The 1992 novel Death and Nightingales by Eugene McCabe mentions him numerous times.

The Irish rebel song by Dominic Behan "Come Out, Ye Black and Tans" contains a reference to Parnell:

Come let me hear you tell

How you slandered great Parnell,

When you thought him well

and truly persecuted,

Where are the sneers and jeers

That you bravely let us hear

When our heroes of '16 were executed?

See also

Notes

- ^ Most contemporaries pronounced his name /pɑːrˈnɛl/, with the stress on the second syllable. Parnell himself disapproved of that pronunciation but pronounced his name /ˈpɑːrnəl/, with the stress on the first syllable.

- ^ A land bill introduced by party leader Isaac Butt in 1876 was voted down in the House of Commons, with 45 of his own MPs voting against him.

- ^ This is based on a 1928 letter from a radical Land League activist, Thomas J. Quinn, to William O'Brien, found in the William O'Brien Papers, University College Cork. Quinn, who emigrated to Colorado in 1882, told O'Brien that in Colorado, he had made the acquaintance of the former radical Land League organiser Patrick Joseph Sheridan, who privately told him that he had sworn Parnell into the IRB under those circumstances. The historians Paul Bew and Patrick Maume, who discovered this material, state that Quinn was probably reporting correctly what Sheridan had told him, but it cannot be proven that Sheridan was telling the truth.[41]

- ^ In the end, she received a much smaller amount and was swindled out of even that. Furthermore, Parnell tried to leave her his family estate, but he neglected to do the legal work and his brother took it all.[48]

- ^ Finnegans Wake, p. 25, describing HCE, refers to Parnell's support for tenants and later divorce scandal: "If you were bowed and soild and letdown itself from the oner of the load it was that paddyplanters might pack up plenty and when you were undone in every point fore the laps of goddesses you showed our labourlasses how to free was easy." See also Tindall 1996, pp. 92–93

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Bew 2004.

- ^ "Parnell and the Parnells". glendalough.connect.ie. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hickey & Doherty 2003, pp. 382–385.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 45.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Collins 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Collins 2008, pp. 50–53.

- ^ Foster 1988, p. 415.

- ^ O'Day 1998, p. 77.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 53.

- ^ a b Collins 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 54.

- ^ a b Jackson 2003, p. 56.

- ^ Maume 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Collins 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Collins 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Collins 2008, p. 80.

- ^ "Chronology of Parnell's life". The Parnell Society. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- ^ Jackson 2003, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Boyce 1990.

- ^ Kehoe 2008, ch. 12, "Emissary to the Prime Minister".

- ^ Kehoe 2008, ch. 13, "The Go-between".

- ^ Reynolds's Weekly Newspaper, Sunday 16 November 1890, issue 2101

- ^ The Daily News, 17 November 1890, issue 13921

- ^ Birmingham Daily Post, 17 November 1890, issue 10109.

- ^ Oldstone-Moore 1995, pp. 94–110.

- ^ Magnus 1960, p. 390–394.

- ^ Kee 1994.

- ^ "Charles Stewart Parnell". University College Cork. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006.

- ^ Lyons 1973, pp. 600–602.

- ^ Horgan 1948, p. 50.

- ^ O'Keefe 1984.

- ^ McCartney & Travers 2006.

- ^ Mastony 2010.

- ^ Lawlor 2010.

- ^ O'Beirne 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Roberts 1999, pp. 456–457.

- ^ O'Brien 1898, p. 137.

- ^ Kettle 1958, p. 69.

- ^ Bew 2011.

- ^ Lyons 1973, p. 615.

- ^ O'Brien 1898, p. 357.

- ^ Taylor 1980, p. 91.

- ^ Lyons 1973, pp. 459–461, 604.

- ^ Gifford & Seidman 1989, p. 172.

Sources

- Bew, Paul (1980). Charles Stewart Parnell. Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-1886-1.

- Bew, Paul (23 September 2004). "Parnell, Charles Stewart (1846–1891)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21384. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bew, Paul (2011). Enigma A New Life of Charles Stewart Parnell: Enigma. Gill Books. ISBN 978-0-7171-5193-6.

- Boyce, David George (1990). Nineteenth-century Ireland: The Search for Stability. Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-1620-1. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Callanan, Frank (1992). The Parnell Split, 1890–91. Syracuse University Press.

- Collins, M.E. (2008). Movements For Reform 1870–1914. The Educational Company. ISBN 978-1845360030. Text for Leaving Certificate History exams, covering Later Modern Irish History, "Topic 2 for Ordinary and Higher Level."

- Flynn, Kevin Haddick (4 April 2005). "Parnell, The Rebel Prince". History Today. 55. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Foster, Robert Fitzroy (1988). Modern Ireland, 1600–1972. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013250-2.

- Gifford, Don; Seidman, Robert J. (1989). Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06745-5. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Hickey, D. J.; Doherty, J. E., eds. (2003). A New Dictionary of Irish History from 1800. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-2520-3. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Horgan, John J. (1948). Parnell to Pearse. Dublin: Browne and Nolan. ASIN B001A4900Q.

- Jackson, Alvin (2003). Home Rule: An Irish History, 1800–2000. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-522048-3. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Kee, Robert (1994). The Laurel and the Ivy. ISBN 0-14-023962-6. A detailed political biography

- Kehoe, Elisabeth (2008). Ireland's misfortune: the turbulent life of Kitty O'Shea. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-486-9. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Kettle, Andrew (1958). Kettle, Laurence J. (ed.). The Material for Victory: Being the Memoirs of Andrew J. Kettle. Dublin: Fallon. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Larkin, Emmet (1961). "The Roman Catholic Hierarchy and the Fall of Parnell". Victorian Studies. 4 (4): 315–336. JSTOR 3825041.

- Lawlor, David (April 2010). "Political priests: the Parnell split in Meath". History Ireland. Vol. 18, no. 2. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Lyons, F. S. L. (1973). Charles Stewart Parnell. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-3939-2.

- McCartney, Donal; Travers, Pauric (2006). The Ivy Leaf: The Parnells Remembered : Commemorative Essays. Dublin: University College Press. ISBN 978-1-904558-60-6. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Magnus, Sir Philip Montefiore (1960). Gladstone: A Biography. Dutton. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Mastony, Colleen (1 September 2010). "Was Chicago home to the country's 1st female cop?". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Maume, Patrick (1999). The long gestation: Irish nationalist life 1891–1918. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780717127443. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Mulhall, Daniel (2010). "Parallel Parnell: Parnell delivers Home Rule on 1904". History Ireland. 18 (3): 30–33.

- Murphy, William Michael (1986). The Parnell myth and Irish politics, 1891–1956. Lang.

- O'Beirne, John Ranelagh (2012). A Short History of Ireland (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-1139789264. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- O'Brien, R. Barry (1898). The Life of Charles Stewart Parnell 1846~1891. p. 137.

- O'Day, Alan (1998). Irish Home Rule, 1867–1921. Manchester UP. ISBN 9780719037764. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- O'Keefe, Timothy J. (1984). "The Art And Politics Of The Parnell Monument". Eire-Ireland. 19 (1): 6–25.

- Oldstone-Moore, Christopher (1995). "The Fall of Parnell: Hugh Price Hughes and the Nonconformist Conscience". Éire-Ireland. 30 (4): 94–110. doi:10.1353/eir.1995.0059. ISSN 1550-5162. S2CID 159212205.

- Roberts, Andrew (1999). Salisbury: Victorian Titan. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-81713-0. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Report of the 1888 Special Commission to Inquire into Charges and Allegations Against Certain Members of Parliament and Others. H.M. Stationery Office. 1890. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1980). Politicians, Socialism, and Historians. ISBN 9780241104866. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Tindall, William York (1996). A Reader's Guide to Finnegans Wake. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0385-6.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Historiography

- Foster, Roy (1991). "Interpretations of Parnell". Studies: An Irish Quarterly. 80 (321): 349–357. JSTOR 30091589. Reviews the many interpretations of his personality, political ideas, and historical significance; says none are completely satisfying.

Further reading

- Boyce, D. George; O'Day, Alan, eds. (1991). Parnell in Perspective.

- Brady, William Maziere (1883). (1 ed.). London: Robert Washbourne.

- English, Richard. Irish Freedom: A History of Nationalism in Ireland (Macmillan, 2007)

- Finnegan, Orla and Ian Cawood. "The Fall of Parnell: Orla Finnegan and Ian Cawood Show That the Reasons for Parnell's Fall in 1890 Are Not as Straightforward as They May Appear at First Sight," History Review (Dec. 2003) online

- Foster, R. F. Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890–1923 (2015) excerpt Archived 28 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Harrison, Henry (1931). Parnell Vindicated: The Lifting of the Veil. Constable. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020. Harrison's two books defending Parnell were published in 1931 and 1938. They have had a major impact on Irish historiography, leading to a more favourable view of Parnell's role in the O'Shea affair. Lyons 1973, p. 324 commented that Harrison "did more than anyone else to uncover what seems to have been the true facts" about the Parnell-O'Shea liaison.

- Houston, Lloyd (Meadhbh) (2017). "A portrait of the chief as a general paralytic: rhetorics of sexual pathology in the Parnell split". Irish Studies Review. 25 (4): 472–492. doi:10.1080/09670882.2017.1371105. S2CID 149234858. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- León Ó Broin. Parnell (Dublin: Oifig an tSoláthair 1937)

- Kee, Robert. The Green Flag, (Penguin, 1972) ISBN 0-14-029165-2

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1896). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 46. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Lyons, F. S. L. (1973a). "The Political Ideas of Parnell". Historical Journal. 16 (4): 749–775. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00003939. JSTOR 2638281. S2CID 153781140.

- Lyons, F. S. L. . The Fall of Parnell, 1890–91 (1960) online Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- McCarthy, Justin, A History of Our Own Times (Vols. I–IV 1879–1880; Vol. V 1897); reprinted in paperback i.a. by Nabu Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-177-88693-2

When Parnell was rejected by the majority of his parliamentary party, McCarthy assumed its chairmanship, a position which he held until 1896.

External links

Charles Stewart Parnell

- The Parnell Society website

- Charles Parnell Caricature by Harry Furniss – UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Charles Stewart Parnell