Battle of Cape Henry

| Battle of Cape Henry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Aerial view of Cape Henry | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8 ships of the line |

7 ships of the line 1 frigate | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

30 killed 73 wounded[2][3] |

72 killed 112 wounded[4] | ||||||

The Battle of Cape Henry was a naval battle in the American War of Independence which took place near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay on 16 March 1781 between a British squadron led by Vice Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot and a French fleet under Admiral Charles René Dominique Sochet, Chevalier Destouches. Destouches, based in Newport, Rhode Island, had sailed for the Chesapeake as part of a joint operation with the Continental Army to oppose the British army of Brigadier General Benedict Arnold that was active in Virginia.

Destouches was asked by General George Washington to take his fleet to the Chesapeake to support military operations against Arnold by the Marquis de Lafayette. Sailing on 8 March, he was followed two days later by Admiral Arbuthnot, who sailed from eastern Long Island. Arbuthnot's fleet outsailed that of Destouches, reaching the Virginia Capes just ahead of Destouches on 16 March. After manoeuvring for several hours, the battle was joined, and both fleets suffered some damage and casualties without losing any ships. However, Arbuthnot was positioned to enter the Chesapeake as the fleets disengaged, frustrating Destouches' objective. Destouches returned to Newport, while Arbuthnot protected the bay for the arrival of additional land troops to reinforce General Arnold.

Background

In December 1780, British General Sir Henry Clinton sent Brigadier General Benedict Arnold (who had changed sides to the British the previous September) with about 1,700 troops to Virginia to do some raiding and to fortify Portsmouth.[5] General George Washington responded by sending the Marquis de Lafayette south with a small army to oppose Arnold.[6] Seeking to trap Arnold between Lafayette's army and a French naval detachment, Washington asked the French admiral Destouches, the commander of the fleet at Newport, Rhode Island for help. Destouches was wary of the threat posed by the slightly larger British North American fleet anchored at Gardiner's Bay off the eastern end of Long Island, and was reluctant to help.[7]

A storm in early February damaged some of Arbuthnot's fleet, which prompted Destouches to send a squadron of three ships south shortly after. When they reached the Chesapeake, the British ships supporting Arnold moved up the shallow Elizabeth River, where the French ships were unable to follow. The French fleet returned to Newport, having as their only success the capture of HMS Romulus, a heavy frigate that was one of several ships sent by the British to investigate the French movements. This modest success, and the encouragement of General Washington, prompted Destouches to embark on a full-scale operation. On 8 March, Washington was in Newport when Destouches sailed with his entire fleet, carrying 1,200 troops for use in land operations when they arrived in the Chesapeake.[6][7]

Vice-admiral of the White Mariot Arbuthnot, the British fleet commander in North America, was aware that Destouches was planning something, but did not learn of Destouches' sailing until 10 March, and immediately led his fleet out of Gardiner Bay in pursuit. He had the speed advantage of copper-clad[8] vessels and a favourable wind, and reached Cape Henry on 16 March, slightly ahead of Destouches.[7]

-

Captain Sochet Des Touches

-

Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot

Battle

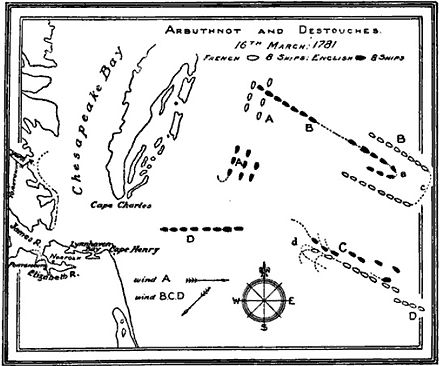

Although the two fleets both had eight ships in their lines, the British had an advantage in firepower: the 90-gun HMS London was the largest ship of either fleet (compared to the 80-gun Duc de Bourgogne), while the French fleet also included the recently captured 44-gun Romulus, the smallest vessel on either line. When Arbuthnot spotted the French fleet to his northeast at 6 am on 16 March, they were about 40 nmi (74 km) east-northeast of Cape Henry.[7] Arbuthnot came about, and Destouches ordered his ships to form a line of battle heading west, with the wind. Between 8 and 9 am the winds began shifting, but visibility remained poor, and the two fleets manoeuvred for several hours, each seeking the advantage of the weather gage. [9] From 0815, he French were sailing close-hauled and had the weather gage, and around 0930, Destouches ordered to wear ship in sequence. As they executed the order, the topsail yards of Ardent and Éveillé broke, slowing and disorganising the Destouches' battle line, and the British seized the opportunity to close in. Destouches ordered another turn, further closing to the British, but allowing Ardent and Éveillé to repair and return to their stations, which they did by 1100. [10]

By 1 pm the wind had stabilised from the northeast, and Arbuthnot was coming up on the rear of the French line as both headed east-southeast, tacking against the wind.[9] Destouches ordered to wear ship in sequence again, and brought his line around in front of the advancing British line. With this manoeuvre he surrendered the weather gage (giving Arbuthnot the advantage in determining the attack), but it also positioned his ships relative to the wind such that he could open his lower gundecks in the heavy seas, which the British could not do without the risk of water washing onto the lower decks.[9]

Arbuthnot responded to the French manoeuvre by ordering his fleet to wear. When the ships in the van of his line made the maneuver, they were fully exposed to the French line's fire, and consequently suffered significant damage.[9] At 1330, the vanguards of both squadron engaged, the French Crossing the T of the three first British ships.[11] Robust, Europe, and Prudent were virtually unmanageable due to damage to their sails and rigging. Arbuthnot kept the signal for maintaining the line flying, and the British fleet thus lined up behind the damaged vessels.[2]

As Conquérant closed in to Robust, a cannonball struck her wheel, killed four helmsmen and sending her Into the wind. the 74-gun Royal Oak and the 100-gun London closed within pistol range, but a lucky shot from Conquérant took off London's topsail yard, forcing her to stop. Conquérant remained exposed for another 30 minutes before she managed to establish a jury rigging and return to the French battle line.[4]

After one hour, Destouches at this point again ordered his fleet to wear in succession, and his ships raked the damaged British ships once more before pulling away to the east.[2] The British ships were too damaged to pursue.[11]

Aftermath

French casualties were 72 killed and 112 wounded, while the British suffered 30 killed and 73 wounded.[2] Arbuthnot pulled into Chesapeake Bay, thus frustrating the original intent of Destouches' mission, while the French fleet returned to Newport.[1] After transports delivered 2,000 men to reinforce Arnold, Arbuthnot returned to New York. He resigned his post as station chief due to age and infirmity in July and left for England, ending a stormy, difficult, and unproductive relationship with General Clinton.[6][12]

On 17 March, Destouches held a war council, which concluded that the ships were too damaged to resume combat, and decided to call Newport to repair.[4]

The United States Congress voted officials thanks to Destouches.[13] General Washington, unhappy that the operation had failed, wrote a letter that was mildly critical of Destouches. This letter was intercepted and published in an English newspaper, prompting a critical response to Washington by the Comte de Rochambeau, the French army commander at Newport.[1] The Comte de Barras, who arrived in May to take command of the Newport station, justified Destouches' decision not to pursue the attack: "It is a principle in war that one should risk much to defend one's positions, and very little to attack those of the enemy."[14] Naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan points out that "this aversion from risks [...] goes far to explain the French want of success in the war."[15]

Lafayette, when he learned of the French failure, turned back north to rejoin Washington. Washington then ordered Lafayette to stay in Virginia, having learned of the reinforcements sent to Arnold.[6] Although the French operation to support Lafayette was unsuccessful, the later naval operations by the Comte de Grasse that culminated in the French naval victory in the September 1781 Battle of the Chesapeake paved the way for a successful naval blockade and land siege of Lord Cornwallis' army at Yorktown, Virginia.[16]

Order of battle

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Commander | Casualties | Notes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||||

| Robust | Third rate | 74 | Captain Phillips Cosby[14] | 15 | 21 | 36 | ||||

| Europe | Third rate | 64 | Captain Smith Child[14] | 8 | 19 | 27 | ||||

| Prudent | Third rate | 64 | Captain Thomas Burnet[14] | 7 | 24 | 31 | ||||

| Royal Oak | Third rate | 74 | Captain William Swiney[14] | 0 | 3 | 3 | Arbuthnot's flag | |||

| London | Second rate | 90 | Captain David Graves[14] | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sir Thomas Graves' flag | |||

| Adamant | Fourth rate | 50 | Captain Gideon Johnstone[14] | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Bedford | Third rate | 74 | Captain Edmund Affleck[14] | 0 | 0 | 0 | Morrissey probably incorrectly lists Bedford with 64; others, e.g. Mahan (1898), p. 492, list her as carrying 74 guns. | |||

| America | Third rate | 64 | Captain Samuel Thompson[14] | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Casualty summary: 30 killed, 67 wounded, 97 total [3] | ||||||||||

- Other ships

- Guadelupe (frigate, 28, Hugh Robinson)[14]

- Pearl (frigate, 32, George Montagu)[14]

- Iris (frigate, 32, George Dawson)[14]

- Medea (frigate, 28, Henry Duncan)[14]

| Ship | Type | Guns | Commander | Casualties | Notes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||||

| Conquérant | 74-gun | 74 | Charles-Marie de la Grandière[19] | 43 | 50 | 93 [4] | Lost her rudder and most of her rigging [20] | |||

| Provence | 64-gun | 64 | Louis-André-Joseph de Lombard[21] | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Ardent | 64-gun | 64 | Charles-René-Louis Bernard de Marigny[22] | 19 | 35 | 54 | Mainmast damaged [20] | |||

| Neptune | 74-gun | 74 | Charles de Médine[23] (WIA)[20] | 4 | 2 | 6 | Morrissey and Mahan claim the Neptune as Destouches' flagship. | |||

| Duc de Bourgogne | 80-gun | 80–84 | Louis Nicolas de Durfort[24] | 6 | 5 | 11 | Morrissey apparently confuses this ship with the Bourgogne, 74 guns; other sources uniformly identify her as the Duc de Bourgogne. In French rating, Duc de Bourgogne was a 80-gun ship (Lapeyrouse, p. 170). She might have actually carried 84 guns (Mahan p. 492). | |||

| Jason | 64-gun | 64 | Jean Isaac Chadeau de la Clocheterie[25] | 5 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Éveillé | 64-gun | 64 | Armand Le Gardeur de Tilly[23] | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Romulus | Fifth rate | 44 | Jacques-Aimé Le Saige de La Villèsbrunne[21] | 2 | 1 | 3 | This was a two-deck ship built by the British in 1777.[26] | |||

| Casualty summary: 72 killed, 112 wounded, 184 total.[4] | ||||||||||

- Other ships

- Hermione (frigate, 36, Latouche)[14][23]

- Gentille[27][28] (frigate, 32, Mengaud de la Haye)

- Fantasque (14, M. de Vaudoré)[29]

- Surveillante (frigate, 32, Jean-Marie de Villeneuve Cillart) [30]

Legacy

The battle has been memorialized by American singer-songwriter Todd Snider in "The Ballad of Cape Henry"[31] on his 2008 album Peace Queer:

Cape Henry, Cape Henry, the battlefield's on fire

White water, white water, with those flames climbing higher

We fired our cannon at least two hours or more

Cape Henry, Cape Henry off of that old Virginia shore

Although there is a marker commemorating the Battle of the Chesapeake at the Cape Henry Memorial in Virginia, there is no recognition of this battle at the site.[32]

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c Perkins, pp. 322–323.

- ^ a b c d Mahan (1898), p. 491.

- ^ a b Lapeyrouse, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b c d e Monaque (2000), p. 58.

- ^ Russell, p. 217–218.

- ^ a b c d Russell, p. 254.

- ^ a b c d Mahan (1898), p. 489.

- ^ "Coppering" a ship had, among other benefits, the reduction of accumulations on the hull of foreign matter that increased drag. (McCarthy, p. 103).

- ^ a b c d Mahan (1898), p. 490.

- ^ Monaque (2000), p. 56.

- ^ a b Monaque (2000), p. 57.

- ^ Davis, p. 45.

- ^ Monaque (2000), p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mahan (1898), p. 492.

- ^ Mahan (1898), p. 493.

- ^ Russell, pp. 274–305.

- ^ Morrissey, p. 51.

- ^ Troude (1867), p. 98.

- ^ Gardiner, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Troude (1867), p. 99.

- ^ a b Gardiner, p. 140.

- ^ Balch, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Gardiner, p. 112.

- ^ La Jonquière, p. 95.

- ^ Mascart, p. 453.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 88.

- ^ Beatson (1804), p. 273.

- ^ Mahan (1898), p. 492.

- ^ Most sources list Fantasque as 64 guns en flûte. She was an older ship of the line, converted for use as a transport and hospital ship. (Smith, p. 58).

- ^ Contenson (1934), p. 159.

- ^ LastFM: The Ballad of Cape Henry.

- ^ National Park Service: Cape Henry Memorial.

Bibliography

- Balch, Thomas Willing; Balch, Edwin Swift; Balch, Elise Willing (1895). The French in America During the War of Independence of the United States, 1777–1783, Volume 2. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. p. 175. OCLC 2183804.

- Beatson, Robert (1804). Naval and military Memoirs of Great Britain, From 1727 to 1783, Volume 6. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme. OCLC 4643956.

- Contenson, Ludovic (1934). La Société des Cincinnati de France et la guerre d'Amérique (1778–1783). Paris: éditions Auguste Picard. OCLC 7842336.

- Davis, Burke (1970). The Campaign That Won America: the Story of Yorktown. New York: Dial Press. OCLC 248958859.

- Gardiner, Asa Bird (1905). The Order of the Cincinnati in France. United States: Rhode Island State Society of Cincinnati. p. 112. OCLC 5104049.

- La Jonquière, Christian (1996). Les Marins Français sous Louis XVI: Guerre d'Indépendance Américaine (in French). Issy-les-Moulineaux Muller. ISBN 978-2-904255-12-0. OCLC 243902833.

- Goodwin, Peter (2002). Nelson's Ships: A History Of The Vessels In Which He Served, 1771–1805. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1007-7. OCLC 249275709.

- Lapeyrouse Bonfils, Léonard Léonce (1845). Histoire de la Marine Française, Volume 3 (in French). Paris: Dentu. OCLC 10443764.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1898). Major Operations of the Royal Navy, 1762–1783: Being chapter XXXI in The royal navy. A history. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 492. OCLC 46778589.

- Mascart, Jean (2000). La Vie et les Travaux du Chevalier Jean-Charles de Borda, 1733–1799 (in French). Paris: Presses Paris Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-84050-173-2. OCLC 264793608.

- McCarthy, Michael (2005). Ships' Fastenings: From Sewn Boat to Steamship. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-451-9. OCLC 467080350.

- Monaque, Rémi (2000). Les aventures de Louis-René de Latouche-Tréville, compagnon de La Fayette et commandant de l'Hermione (in French). Paris: SPM.

- Morrissey, Brendan (1997). Yorktown 1781: the World Turned Upside Down. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-688-0. OCLC 39028166.

- Perkins, James Breck (1911). France in the American Revolution. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 177577.

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0783-5. OCLC 44562323.

- Smith, Fitz-Henry (1913). The French at Boston during the Revolution: With Particular Reference to the French Fleets and the Fortifications in the Harbor. Boston: self-published. OCLC 9262209.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France (in French). Vol. 2. Challamel ainé.

- Clark, William Bell, ed. (1964). Naval Documents Of The American Revolution, Volume 1 (Dec. 1774 – Sept. 1775). Washington D.C., U.S. Navy Department.

External links

- "LastFM: The Ballad of Cape Henry". Last.fm Ltd. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- "National Park Service: Cape Henry Memorial". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

This is a recording of the text of the article on the Battle of Cape Henry read on 21 May 2020.