Anatahan (film)

| Anatahan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Josef von Sternberg |

| Screenplay by | Josef von Sternberg Tatsuo Asano |

| Produced by | Kazuo Takimura |

| Cinematography | Josef von Sternberg |

| Edited by | Mitsuzō Miyata |

| Music by | Akira Ifukube |

Production company | Daiwa Production Inc. |

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Languages | Japanese English |

| Budget | $375,000[2] |

Anatahan (アナタハン), also known as The Saga of Anatahan, is a 1953 black-and-white Japanese film war drama directed by Josef von Sternberg,[3][4] with special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya. The World War II Japanese holdouts on Anatahan, then part of the South Seas Mandate of Imperial Japan, now one of the Northern Mariana Islands of the United States, also inspired a 1998 novel, Cage on the Sea.

It was the final work directed by noted Hollywood director Josef von Sternberg, although Jet Pilot was released later. Von Sternberg had an unusually high degree of control over the film, made outside the studio system, which allowed him to not only direct, but also write, photograph, and narrate the action. It opened modestly well in Japan. It did poorly in the US, where von Sternberg continued to recut the film for four more years. He abandoned the project and went on to teach film at UCLA for most of the remainder of his lifetime. The film was screened within the official selection during the 14th Venice Film Festival in 1953.

Plot

Josef von Sternberg directed, photographed and provides the voice-over narration. He wrote the screenplay from a novel based on actual events by Michiro Maruyama, translated into English by Younghill Kang, about twelve Japanese seamen who in June 1944, are stranded on an abandoned-and-forgotten island called Anatahan for seven years. The island's only inhabitants are the overseer of the abandoned plantation and an attractive young Japanese woman.

Discipline is enforced by a former warrant officer but ends when he suffers a catastrophic loss of face. Soon, discipline and rationality are replaced by a struggle for power and the woman. Power is represented by a pair of pistols found in the wreckage of an American airplane, so important that five men pay with their lives in a bid for supremacy.

Background

Anatahan, one of the Mariana Islands in Micronesia, was the scene of a wartime stranding of thirty Japanese sailors and soldiers and one Japanese woman in June 1944. The castaways remained in hiding until surrendering to a US Navy rescue team in 1951, six years after Japan was defeated by allied forces.[5] The twenty who survived the ordeal were warmly received upon their return to post-war Japan. International interest, including an article in Life of 16 July 1951, inspired Josef von Sternberg to adapt the story to a fictional film rendering of the events.[5][6]

By the end of 1951, lurid personal accounts surfaced describing the deaths and disappearances arising from inter-male competition for the only woman on the island, Higo Kazuko.[7] These sensationalised depictions produced a backlash in popular opinion and sympathy for the survivors cooled. The end of the post-war US occupation of Japan in 1952 saw a revival of political and economic sovereignty and a desire among the Japanese to suppress memories of wartime suffering. This “rapid transformation of the political and social climate” influenced perceptions of Sternberg's Saga of Anatahan in Japan.[8]

Production

Daiwa and Towa Corporations

Daiwa Productions, Inc., an independent Japanese film production company, was founded in 1952 solely for the purpose of making the film Saga of Anatahan. The co-executives included film director Josef von Sternberg, Nagamasa Kawakita and Yoshio Osawa, the latter two entrepreneurial international film distributors.[9][10]

Kawakita established the Towa Trading Company in 1928 to promote an exchange of Japanese and European films in “the urban art cinema market.” He also acted as a representative for German film corporation UFA GmbH in Japan. German director-producer Arnold Fanck joined with Kawakita in 1936 to produce the German-Japanese propaganda film The Daughter of the Samurai, entitled The New Earth in English language releases and Die Tocher der Samurai in Germany, to foster mutual cultural bonds between the countries. Filmed entirely in Japan, the high-profile, big-budget feature was endorsed and promoted by Reich Minister of Propaganda Josef Goebbels in Nazi Germany, where it opened to critical acclaim in 1937.[11]

Sternberg travelled to Japan in 1937 shortly after ending his professional ties with Paramount and Columbia Pictures. He met with Japanese critics and film enthusiasts who had studied and admired his silent and sound films. Producer Kawakita and director Fanck were filming The New Earth, and Sternberg visited them on location to discuss the possibilities for movie collaboration. When war broke out in 1939 the talks were suspended. Both Kawakita and Osawa served Imperial Japan throughout the war producing propaganda films in China and Japan, respectively. When Japan was defeated in 1945 the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCPA) designated both producers as Class B war criminals, barring them from the Japanese film industry until 1950.[12]

Pre-production

Sternberg reestablished contact with Kawakita in 1951 and in 1952 the producer agreed to finance a large-budget film based on the “Anatahan incident”, engaging the Toho company as distributor. Kazuo Takimura was hired as credited producer on the project. Kawakita and Osawa went un-credited. Eiji Tsuburaya, soon to be renowned for his Godzilla series, was hired as special effects director. The film score and sound effects were created by composer Akira Ifukube.[13]

From his arrival in Japan in August 1952, Sternberg examined numerous accounts of the Anatahan affair translated into English, and from among these selected the memoir of survivor Michiro Maruyama for adaption to film. Scriptwriter Tatsuo Asano was enlisted to add local vernacular to the film dialogue. Sternberg's narrative requirements reduced the number of participants to thirteen men and one woman and spanned the entire seven years they spent in isolation. The actual number of castaways in 1944 had been reported at 30-32 people, of whom twenty survived.[14]

Unable to obtain permission to use the Toho studio facilities in Tokyo, producer Osawa moved the project to the Okazaki Industrial Park in Kyoto, where the multiple open air set was constructed. Sternberg arrived at the ad hoc studios with two Japanese interpreters and launched the painstaking collaborative process in which he would wield control over every aspect of the co-production.[15][16][17] A highly detailed storyboard was prepared – “the Anatahan Chart” – providing schematics for every aspect of the narrative. Flow charts for actors were colour-coded to indicate timing and intensity of emotions, action and dialogue so as to dictate the “psychological and dramatic” continuity of each scene. These visual aids served, in part, to obviate misunderstandings related to language barriers. Sternberg spoke no Japanese and the crew and actors spoke no English.

Sternberg selected the actors based on “his first impression based on their appearance [and] disregard[ed] their acting skills.” The 33-year old Kozo Okazaki, a second unit cameraman, was drafted during pre-production to serve a cinematographer for the project. Virtually the entire movie was shot amid the stylised and highly crafted sets. Production began in December 1952 and ended in February 1953. Anatahan (entitled The Saga of Anatahan (アナタハン)) was released to Japanese audiences in June and July 1953.[18][16]

Filming

When Sternberg arrived to begin pre-production in 1952 the dramatized and sometimes lurid renditions of the Anatahan events were widely circulating in the press. When Josef von Sternberg was asked by a French critic why he had gone to the Far East to build a studio set to film Anatahan, when he could have constructed an identical set in a Hollywood back lot, he replied "because I am a poet".[19]

Sternberg added his narrative voice over to the film in post-production, with a translation in Japanese subtitles. The “disembodied” narration explains “the action, events and Japanese culture and rituals.” [20] A pamphlet was also produced by the director that provided a personal declaration to theatregoers, emphasising that the production was not a historical rendering of an event during WWII, but a timeless tale of human isolation – a universal allegory.[21]

Release

The director issued press statements promising that his upcoming movie would be an artistic endeavor, pleasing to Japanese audiences, rather than a forensic recreation of a wartime disaster.[20]

Kawakita presented The Saga of Anatahan at the Venice Film Festival in 1953 where it was overshadowed by another Kawakita entry, director Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu.[22] When Kawakita edited Anatahan for distribution in Europe, Sternberg’s “monotonous” narration was replaced with that of a Japanese youth, delivering the same text in broken English so as to make it more “authentically” Japanese to English speaking audiences.[23]

The Saga of Anatahan premiered in June 1953 following publicity in major and local newspapers. The film received a limited theatrical released in the United States in 1954.[24] The premiere and first-run public showings in Tokyo and Kyoto received “lukewarm” support. A modest commercial success, investors broke even on the project.[16]

Reception

Critics questioned why Sternberg had adapted a story that might trigger "unpleasant feelings" among many Japanese who had been traumatized by war and defeat.[20] Critical evaluation of the film was uniformly hostile, including a multi-journalist round-table published in Kinema Junpo. As film historian Sachiko Mizuno reports:

Journalists lambasted the film by severely critiquing Sternberg’s direction, his exotic view, the cast’s amateurish acting, and his idea of making a film out of the story in the first place. They criticized Kawakita and Osawa for granting Sternberg complete control over an expensive film production that only objectified the Japanese on screen.[25]

Patrick Fleet writing in the Evening Post, was highly critical of the film, saying "...but the treatment is generally heavy-handed and at times tedious" and "The film is re commended only for devotees of the "art of cinema ” — and more as a curiosity than anything else."[26]

Criticism was also directed at Sternberg for adopting a sympathetic attitude towards the lone woman on the island, Higa Kazuko, portrayed by Akemi Negishi, and the male survivors. Condemnation of the film was particularly harsh from critic Fuyuhiko Kitagawa, accusing Sternberg of moral relativism and being out of touch with Japanese post-war sentiments.[23][16]

Anatahan was the favorite film of Jim Morrison, who was a film student at University of California, Los Angeles when von Sternberg had been serving as a professor.[27] Film-maker François Truffaut reportedly cited it as one of the ten best American films ever made.[28]

Cast

- Akemi Negishi as the 'Queen Bee', Keiko Kusakabe

- Tadashi Suganuma as Kusakabe, Husband of Keiko

- Kisaburo Sawamura as Kuroda

- Shōji Nakayama as Nishio

- Jun Fujikawa as Yoshisato

- Hiroshi Kondō as Yanaginuma

- Shozo Miyashita as Sennami

- Tsuruemon Bando as Doi

- Kikuji Onoe as Kaneda

- Rokuriro Kineya as Marui

- Daijiro Tamura as Kanzaki

- Chizuru Kitagawa

- Takeshi Suzuki as Takahashi

- Shiro Amikura as Amanuma

- Josef von Sternberg as voice of narrator (uncredited)

References

- ^ (in Japanese) Jmdb.ne.jp Accessed 10 February 2009

- ^ "'How We Beat 'Em Pix' Irk Nips, So They Slug U.S. With Own Hay-Makers". Variety. August 19, 1953. p. 2. Retrieved March 16, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (May 18, 1954). "The Screen in Review; 'Ana-ta-han,' Filmed in Japan, at the Plaza". The New York Times.

- ^ "Screen: Von Sternberg's Coda". The New York Times. May 19, 1977.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, 1978

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p. 17

- ^ Mizuno, 2009 p. 9, 14, 17

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p 19, 20-21, 22

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p 10-11

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 169-170

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p 11-12

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p .13

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p.14, 16-17

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p. 14

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p.14

- ^ a b c d Gallagher 2002

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 174

- ^ Mizuno, 2009 p. 15 – 16, 17

- ^ Sarris, 1966, p. 53

- ^ a b c Mizuno, 2009 p. 17

- ^ Mizuno, 2009 p. 18-19

- ^ Mizuno, 2009. p. 19 (see footnote 41)

- ^ a b Mizuno, 2009. p. 19-20

- ^ Eyman, 2017.

- ^ Mizuno, 2009 p. 19

- ^ Fleet, Patrick (1954-10-02). "Royal Tour Epic Makes You You Are There Too". Evening Post. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/jim-morrisons-favourite-film-is-an-unsung-classic/

- ^ "'Saga Of Anatahan' To Be Screened At HC". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. 1972-10-26. p. 24. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

Sources

- Baxter, John. 1971. The Cinema of Josef von Sternberg. The International Film Guide Series. A.S Barners & Company, New York.

- Eyman, Scott. 2017. Sternberg in Full: Anatahan. Film Comment, May 15, 1017. Retrieved 29 May 2018. https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/sternberg-full-anatahan/

- Gallagher, Tag. 2002. Josef von Sternberg. Senses of Cinema, March 2002. Retrieved 29 May 2018. http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/feature-articles/sternberg/

- Mizuno, Sachiko. 2009. The Saga of Anatahan and Japan. Transnationalism and Film Genres in East Asian Cinema. Dong Hoon Kom, editor, Spectator 29:2 (Fall 2009): 9-24 http://cinema.usc.edu/assets/096/15618.pdf Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan. 1978. Aspects of Anatahan. Posted January 11, 1978. Retrieved 23. January, 2021. https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2020/12/aspects-of-anatahan-tk/

- Sarris, Andrew: The Films of Josef von Sternberg. New York: Doubleday, 1966. ASIN B000LQTJG4

External links

- Anatahan at IMDb

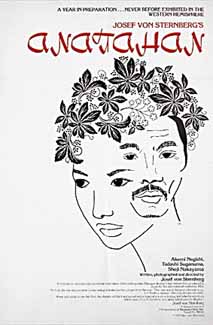

- Italian movie poster