2007 vole plague in Castile and León

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The 2007 vole plague began in early summer 2006 in the province of Palencia, in the Spanish autonomous community of Castile and León.[1] In the summer of 2007, crops in the plateau fields were devastated by rodents. In September 2007, after a summer of severe losses, the density of rodents decreased throughout the community and the plague was institutionally considered to be over. However, there was an abundance of voles during the following months. Only the winter frosts and the low temperatures of November and December reduced vole numbers to normal.

The common vole (Microtus arvalis) was responsible for devastating the crops of the northern plateau. This Eurasian species had only penetrated the Iberian Peninsula as far as the Cantabrian Mountains, where it differentiated and became a subspecies called Microtus arvalis asturianus, beginning to extend its habitat to the south, thus freeing itself from its natural predators, the birds of prey. In normal years, their population did not exceed 100 million, but in the summer of 2007, it is estimated that they reached at least 700 million. They devastated a total of 500,000 hectares of crops and caused losses of 15 million euros. Their voracity led them to be described as the scourge of Castile.[2]

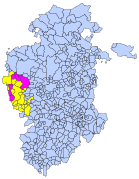

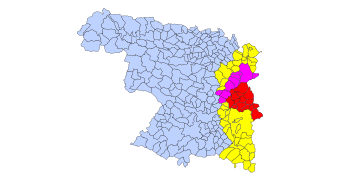

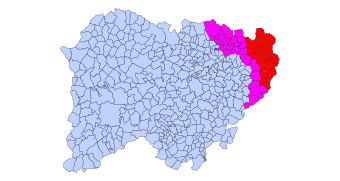

This plague was present throughout the community of Castile and León, the most affected provinces being Valladolid, Segovia, Palencia and Zamora, especially in the areas of Tierra de Campos, and the area bordering Tierra de Medina, where other provinces such as Salamanca and Avila converge. It also came to be located in the municipalities of Aliste, on the verge of crossing into Portugal.[3]

Causes

A number of reasons caused this plague of rodents, which ruined entire crops, especially beets, potatoes, onions, and carrots. Despite the fact that winters in the Meseta are usually the coldest in the Iberian Peninsula, in 2007 temperatures were higher than usual, reducing the number of frosts to almost zero, which, together with the arrival of spring (also with slightly above-average temperatures), led to a population explosion of voles. These animals are characterized by reaching sexual maturity very quickly, reproducing at high speeds with several offspring per litter and several births per year, causing the explosion to occur without too much difficulty.[2]

It has also been pointed out, as a cause of the proliferation of voles, the complaint filed by environmental groups before the Junta of Castile and León, in March 2007, against the use of poison that was being used to stop the incipient plague. The Young Farmers Association (Asociación de Jóvenes Agricultores, ASAJA) has blamed the administration and the environmental groups for the paralyzation of preventive measures which, in their opinion, could have prevented the high magnitude of the crisis.[4]

Voles can transmit diseases to humans, such as tularemia, by direct contact or with dust particles that were in contact with the animal or its feces. The plague could be the cause of 42 cases in the region, officially recognized by the Junta of Castile and León. According to the PSOE of Castile and León, the number of cases could reach 270.[5] In addition, the opening of the hunting season has led the regional executive to request that game should not be consumed for fear of possible infection by this disease.[6]

Extent of the vole by province

Under normal conditions, the typical density of common voles is 5–10 individuals per hectare. During the plague in Castile and León, up to 1,500 rodents per hectare have been recorded in the most affected areas.[7]

The province of Palencia, where the plague originated, is the province most affected by the spread of voles, followed by Valladolid and Zamora. On the other hand, the province of Soria has been the one where the plague has had the least impact.

Consequences of common vole infestations.

From an ecological point of view, vole population explosions have both detrimental and beneficial effects; for example, their burrows improve soil fertility by increasing subway organic matter (such as buried vegetation, feces, or their own decomposing corpses), increase soil aeration and make it more spongy, as well as favor edaphological processes by stirring up the soil in their excavations and facilitating water filtration. Some researchers have even stated that "the abundance of voles in Castilla y León during the last decades has contributed to increasing the faunal diversity of the Douro Valley".[8]

However, they also have harmful effects; one of the most worrying is that they can be a vehicle for the transmission of serious diseases that affect both humans and the animals they feed or live with. Specifically, Microtus arvalis is known in scientific circles as a host of numerous parasites and a carrier of various pathologies, such as viral diseases[9] like rabies or hantavirus, bacterial diseases like leptospirosis (or Weil's disease), listeriosis, borreliosis (or Lyme disease) and, the most dreaded, tularemia. Parasites range from protozoa (babesiosis) to helminths (hydatidosis).

-

The common raven is one of the natural enemies of voles.

-

Hen harrier flying with a vole in its talons.

-

Remains of a vole devoured by a predator (only the head remains).

On the other hand, the abundance of easy prey favors both predators (by providing them with abundant food) and other species, reducing the pressure they suffer as prey. However, given that the duration of the plagues is shorter than the life cycle of most predators when voles begin to become scarce, the rebound effect is produced.[note 1] In fact, some specialists in arvicoline predation claim that the impact of mammals (stable) is greater than that of birds (many of which are migratory) and in the case of the weasel, its abundance curve is a replica of that of voles, with a few months of lag.[10] In short, if the number of animals that need to feed on meat increases, eventually they will target other animals, sometimes attacking endangered species that are vulnerable or of particular interest to humans.

"Although Grouse breeding was enhanced by spikes in mouse populations, there was no residual effect on population size. Instead, there were fewer adult western capercaillie in post-spike years in mouse populations, especially in July counts, because neither foxes nor martens were eliminated. One possible explanation is that predators bred more successfully when mouse populations were abundant, and then killed more tetraonids in winters or at the beginning of the following breeding season."[11]

Focusing on this last aspect, for humans, these demographic explosions are harmful plagues and their iniquitous consequences are multiple and ramify into the most unsuspected fields: the economy, leisure, health, and society, even causing social alarm, so it is not strange that the issue reaches political overtones, being used as a throwing weapon among the various ideological groups.

Consequences for harvests

The common vole is considered the most damaging vertebrate for agriculture, not only in Spain, but in all of Europe, since the abundance of arvicolines is common to the entire Northern Hemisphere. Their main diet consist of tender green stems, although they also take advantage of leaves and the remains of ears of corn. The 2007 plague seems to have emerged in Tierra de Campos (Palencia), and had spread throughout the autonomous community. It has been estimated, without much rigor, that there are more than 200,000 hectares affected in Castile and León and that losses may exceed one million euros.

-

Potato.

-

Beet.

-

Sunflower.

-

Tree.

During the sowing season, voles install their burrows in the ditches and borders, safe from the plows; but when the sowing season is over, they move into the interior of the arable land. In fields of cereal or pastures, they come to form empty stands. There are data from the United States that show that with about 200 rodents per hectare, 5% of the alfalfa[12] is already lost, taking into account that this figure is greatly exceeded in the Castilian plagues, we can get an idea of the dimensions of the disaster. In beets they usually eat the tuber and, although they do not consume the whole plant, they cause its rapid rotting. They also gnaw the stems of sunflowers until they fall to the ground. Although few expected it, voles are also feeding in vineyards, and although they are limited to tender shoots, if they affect the base of the vine shoots, they can spoil the harvests of coming years. Sometimes the damage does not become apparent until it is too late and it is not possible to take corrective measures. Fruit trees do not escape their attack either, since, by gnawing the bark at the base of their trunks, they weaken or destroy them.[13]

Health consequences

Rodents constitute almost half of all known mammalian species and are not only the type of animal that causes the most problems for humans, they are also the largest natural reservoir of contagious pathogens; this is called zoonosis (from the Greek zoon, animal, and nosos, disease). It has already been pointed out, above, that common voles are very active zoonotic agents, even more so during periods of abundance, when it is easier for them to come into contact with people or with the animals that come into contact with them (pets, livestock...).[note 2]

Many of the risks of pathogen transmission are related to recreational activities, which have received less attention than other problems such as economic losses. Plagues often coincide with the holiday period, and many of the children or teenagers living in rural areas have witnessed the massive presence of voles in parks, gardens or kitchen gardens within the urban area itself. Being less aggressive and more clumsy rodents than house mice or rats, they give a false sense of innocence, so it has quickly become fashionable to chase them, capture them or kill them as an added amusement. The danger is, however, considerable, not only because of the possibility of becoming infected with a series of serious diseases (already mentioned), but also because the smallest (even babies) have access to more or less putrefied corpses left on the lawn or in the sandbox of the park where they usually go to play, where, in addition, fleas, ticks and other mites can survive for a long time. Not to mention the swimming pools or irrigation reservoirs in which these animals drown by the dozens every night.

Another risk also related to leisure activities has to do with small game hunting. The Junta of Castile and León, through the Hunting Species section of the General Directorate of Natural Environment of the Ministry of Environment, has been forced to publish a series of tips to avoid problems related to the pest.[note 3] Unfortunately, few had previously been concerned about this issue because they considered it a mere nuisance, at most an extraneous problem to be dealt with by farmers. But the prospect of a poisoned (or suffocated by its muzzle) dog, a hunter infected with tularemia or even poisoned by rodenticides has generated alarm and controversy.[14] The lack of foresight and haste, both on the part of the Hunting Societies (who congratulated themselves on the good expectations for the season), as well as on the part of the competent authorities, has been all too evident. As a result, everyone is trying to throw the baby out with the bathwater, blaming each other.[15]

Administrative consequences

The inoperativeness of the Junta of Castile and León in the face of the rapid expansion of the pest led thousands of farmers in the region to protest in the streets of Valladolid on 2 August in front of the Junta's headquarters to demand solutions.[16][17][18]

Faced with administrative passivity, farmers began to find their own solutions, by digging ditches in which water was poured so that the voles would subsequently fall in and drown. At the head of the search for solutions was the town of Villalar de los Comuneros in Valladolid, which, with the help of its mayor, devised a plow to destroy the rodents' burrows. Both attempts proved to be insufficient.[19]

The first institutional solutions arrived late, on 9 August, when voles were already present in the urban areas of some localities, with the burning of stover, the first locality being Fresno el Viejo, in Valladolid.[20][21]

With its expansion to the wine world and the damage caused, with an estimated 40% loss in the grape harvest, added to the losses it will cause in the livestock sector, the primary sector of Castile and León is doomed.[22][23][24]

All this led many mayors in the area to request the declaration of a catastrophe zone.[20]

Cyclical plagues of common voles in Castile and León

The so-called vole ''plagues'' were practically unknown in Spain until a few decades ago, as confirmed by the naturalist Juan Delibes de Castro in 1989:

"In Spain, the populations of the common vole (Microtus arvalis) were until now very small and were located in certain mountainous enclaves. However, in the present decade they have expanded massively, causing notable crop losses."

Indeed, research carried out in the 1970s by the biologist José Rey located this species only on the southern slopes of the Cantabrian mountain range and in the Sierra de Albarracín and Sierra de Javalambre. The data were corroborated by other specialists.[25] Apparently, the species could have come down some river valleys in the north where alfalfa groves were abundant, although the information is not sufficient.[26] But since the beginning of the 1980s there were already reports of some Microtus arvalis in the province of Valladolid.[27] An expansion of this magnitude is unprecedented among the known ecological phenomena in the Spanish Northern Plateau.

Since then, in the Douro valley there have been demographic explosions of voles every three or four years, in such numbers that they have become a particularly harmful pest for the agricultural economy. If under normal conditions the estimated population density of voles in the Castilian steppe is 5–10 individuals per hectare, in cycles of overabundance they exceed 200 individuals per hectare. This is a minimum figure, since the real numbers are almost impossible to calculate; Juan Delibes de Castro carried out a sampling in several farms in the province of Burgos, noting, in October 1983, up to 1294 specimens per hectare of alfalfa, 382 per hectare of cereal and 182 per hectare of badlands.[28][note 4]

| Density of voles per hectare |

|

The specialist, Ángel María Arenaz, considers it possible to forecast the demographic magnitude of vole infestations by making winter counts. Thus, if in January there are more than 50 individuals per hectare, a dangerous level is foreseeable in summer; but if it is lower, it is normal that there is no danger of invasion. This author even argues that it is possible to advance the forecasts according to the autumn rains: heavier rainfall is unfavourable for reproduction. To make the appropriate forecasts for a given agricultural year, it would be necessary to carry out periodic censuses by means of approved traps, suitably placed in the alfalfa fields during the months of September, February, May and August.[29]

As the naturalist Juan Carlos Blanco points out, "...in Spain there is no information on the subject",[30] except perhaps in certain areas of the Pyrenees or extrapolations made with data from neighbouring countries. Despite the almost routine repetition of these demographic explosions, we lack reliable data and we do not even know the cause.

Regarding the plague that has taken place in the summer of 2007 and which, apparently, is one of the most intense ever, the Junta of Castile and León has provided various information based on that provided by the municipal agrarian chambers and farmers' associations, although obviously these are only estimates, since there is no complete study of the situation. The vole infestation was officially declared a plague through an order of 27 March.[31]

Some rural inhabitants have even accused the environmental movement of "repopulating" the land with hatchery specimens destined to feed the raptors. At the time, the now defunct ICONA was also accused and, at the very least, the autonomous administration is blamed for ignoring the problem, turning its back on farmers to benefit certain ideological groups. The idea of releasing voles is so deeply rooted that it is almost impossible to explain to the farmers that the plagues are due to natural causes.[32] Fernando Franco Jubete explains this legend with the following words:

"...voles are beings created in laboratories and reproduced by millions in unknown farms to be released, as food for raptors, from mysterious SUVs and helicopters. Consequently, the guilty parties are those who consent, finance and execute it: "the Government", "the Environment", "ICONA", "the ecologists"."

— Jubete 2007 [note 5]

It is true that the abundance of voles benefits all types of predators, not only their usual enemies: some nocturnal raptors, such as owls; mustelids, for example, weasels[9] and diurnal raptors such as the black-winged kite;[33] but also all types of general predators such as raptors, canids, felids, corvids, storks, herons, etc.[34] This reduces the pressure on other potential prey, favouring the proliferation of partridges, quails, rabbits and other small animals. But it also increases the number of predators. In some cases, the animals that have been feeding on voles (especially certain raptors) are migratory or even opportunistic species that are not very specialized (such as storks), so the decrease in prey, if it coincides with their departure, may not have any consequences. But stable predators, to adapt to the new situation of "scarcity", must look for other sources of food, which means that they refocus on their most common prey[35] and, being more numerous, provoke a pernicious rebound effect that is hardly favourable.[36]

An expansion such as that of the voles must have originated in an area where the native population was dense and stable; it must also have suffered some kind of dispersing stimulus and found favourable transmission routes (land consolidation, improvements in the transport network, the expansion of irrigation in the river valleys...). Once the durian basin was colonized, the alfalfa fields, its favourite places, would act as shelters from which, under certain favourable conditions, the plague could be unleashed. The hypotheses considered about the triggering of this phenomenon are as follows:

- For some specialists, plants could have some influence on the fertility of animals (phenotypic cause): the area devoted to irrigation in the centre of the Douro Valley has increased exponentially in the last 20 years, precisely when pests have become more common (alfalfa and sugar beet are among their main sources of nutrition). However, population fluctuations can only be explained as a result of an obvious improvement in living conditions in very specific cases that are not cyclical, coupled with the fact that, under normal conditions, "mice in large areas..., consume only 1–2% of the available food. This is because a considerable amount of the plant material, greater than that used by these mammals, is consumed by insects".[37]

- Another hypothesis emphasizes predation as a factor controlling the species. The lack of enemies would accelerate their abundance ("...predation plays an essential role in the abundance cycles of microtines".[35] It has been demonstrated that rodents can multiply massively in the face of a scarcity of natural enemies; furthermore, this is related to biological richness (pests are greater the poorer the ecosystem). The few predators that exist are unable to stop the population increase, but little by little they react, reproducing rapidly and concentrating on the prey expansion centres. The following year, the numerous carnivores (specialists, generalists or opportunists) are enough to decimate the rodent population. As prey are literally exterminated, predators are forced to change their diet.[38] But the alternatives are usually not enough, so the number of hunters gradually declines over two, three or four years until they return to the level of scarcity that allows a new population explosion.[39]

- It is also proposed that the causes would be endogenous (genotypic), the voles themselves would modify their reproductive and social behaviour causing a systemic overabundance or population reduction:[40] Rodents, almost more than any other mammal, have a great reproductive capacity, but this is usually inhibited, causing their populations to remain more or less stable. Sometimes, however, unrestricted reproduction occurs. Under these conditions, a tough internal competition for survival is generated (either for space, food, predation...). It is natural that there is a significant number of marginal individuals, leftovers, who are not able to integrate socially, who lack a stable territory, who have serious difficulties to access food or to reproduce. In short, they occupy the bottom of the social pyramid of the colony. Thus it is intra-population mechanisms that control their density, change odorant signals, communication systems and other mechanisms that affect mainly lower-ranking individuals in which stress increases. Rodents react to stress by increasing their adrenal secretions, reducing their reproductive capacity and becoming more vulnerable to the diseases they themselves carry.[41]

It is essential to differentiate the causes of the expansion of the vole from the original mountainous environments to the Douro valley (non-existent until the early 1980s), from those other causes that provoke the reproductive peaks. It is quite clear that human activities directly affect rodent populations, since their living conditions are unintentionally improved by cultivating their favourite foods or creating favourable habitats for their development.[42] Thus, the first hypothesis serves to explain the colonization of the Northern Plateau, but not the demographic boom or the existence of recurrent ups and downs, otherwise common to the entire arvicoline family:[43] these are natural cycles caused by internal factors (social behaviour), and aided by external ones (feeding-predation).

Pest control and its effects

An essential condition to combat any type of pest is to have as much information, causes, cycles, development. These types of cases occur all the time, but the same solution cannot always be applied. The first thing to do is to identify the responsible party for the damage and then act as quickly as possible.[44] However, in Spain there are not enough updated in-depth studies on the subject and it is necessary to resort to publications from a few years ago, or to extrapolate experiences from abroad. On the other hand, the material found on the Internet or in the media is as abundant as it is biased and unusable (with some exceptions).

According to biologist Juan José Luque-Larena,[45] of the Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenierías Agrarias of the University of Valladolid:

"There is an absolute lack of rigor, a lot of confusion and no research. When avian flu appeared, there was no question that it was necessary to investigate, but anyone can talk about voles."

Preventive measures

A plague in an advanced state is impossible to eradicate, at most its number can be contained, some outbreaks can be eliminated or its damages can be mitigated; but to be successful it is necessary to prevent it, and the first step to do so is the census of the populations of harmful animals. Censuses of voles should be carried out in specific regions, those that are usually the most prone, with approved trapping methods, as indicated above, or by observation.

The census can be the best guide to the future evolution of the rodent population. In the case of Microtus arvalis, if the populations censused in January do not exceed 50 units/ha, the danger can be considered non-existent. If this quantity is exceeded and, even more, if the winter is mild, it is necessary to start acting to prevent the pest.

When food is scarce, the use of poison (always under control of the relevant authorities) is very effective, as voles do not have many options against the baits offered. That is, poison is much more effective in winter.[46]

Other effective preventive measures consist of helping and protecting the natural enemies of small rodents ( raptors, weasels, foxes, storks...): raptors must be protected by law and perches or nesting and breeding sites can be installed.

-

Black-winged Kite on its natural perch.

-

Straw bales are improvised perches for raptors.

-

The fruit of the stramonium, a plant that is often ignored by voles.

-

Deep cleaning of ditches to eliminate burrows.

For small farms, the use of repellent plants can be a good palliative, for example, Solanaceae such as Stramonium, which is toxic because of the atropine and scallopine it contains, or belladonna or other plants of the same family, which also have a high concentration of atropine, especially in the root. Rue, squill, fritillaria and castor bean have a similar function.

Pests are more effective in areas where only one type of farm predominates (and even more so if it is repeated year after year), so that the variation and rotation of crops favours the control of the vole population. The cleaning and care of the field is also a very appropriate measure, but always respecting the biodiversity. The deep tillage of fallow land, the elimination of weeds in farmland, threshing floors, ditches, canals, dry riverbeds (very abundant in some areas of Castile and León) and at the base of trees, contribute to hinder the expansion of voles. Allowing or encouraging stover grazing is doubly effective (cattle crush many burrows and clean the ground). The destruction of their burrows by mechanical means; the creation of food-free zones, i.e., wastelands or areas covered with plastic, or the use of chemical repellents, forces them to concentrate where the traps or poison are placed. In short, the richer the biotopes, the less vulnerable to pests: good agricultural and environmental management is the best weapon to prevent disaster.[47]

Trapping

Trapping voles can be done in a very simple way, since they are unable to jump or climb. The most widespread way is to place small containers filled with water near their feeding troughs, so that they drown; the metal boxes of the French association I.N.R.A. are also very effective.[48]

In any case, trapping is practically useless in large areas, it is only useful (apart from sampling) in small and well controlled areas: parks, gardens, orchards, swimming pools, in general, not very large farms.

Stover burning

In 2005, following EU guidelines and to avoid the risk of fires, the Spanish government banned the burning of stover throughout the national territory (Royal Decree 11/2005 of 22 July 2005, which regulates in Article 13 the activities prohibited in the area of forest fires.)[49] Following the 2007 vole plague, many agricultural associations requested permission to recover this custom as a means of combating the rodents. Although permission has not been granted, the Junta of Castile and León has decided to experiment controlled burning, as an exceptional measure, in some specific points, to evaluate its effectiveness in the fight against the plague. Priority has been given to areas where irrigation predominates or in regions with denomination of origin of agricultural products.

After a few weeks of observation, it seems clear that burning the straw does not produce enough heat to kill them. At most, 200 °C is reached, which affects the top 10 centimetres of the soil, so that the vast majority of specimens are able to take refuge in their burrows.

Some agricultural organizations, specifically ASAJA, COAG, UCCL and UPA,[50] supported by the advice of the engineer Fernando Franco Jubete (also from the Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenierías Agrarias),[51] consider that sporadic burning is ineffective and that it should be generalized to have any success, thus forcing the rodents to take refuge in the so-called firebreaks where chemical measures would be applied.

Although burned areas scare voles away, as they lack food or shelter, and are theoretically sterilized, burning is still pernicious to other species and, after all, is a potential hazard that can have a very negative biological impact: any microorganisms living in the affected 10 cm die, which cancels their ability to aerate and fertilize the soil, sulfur and carbon increase, and nitrogen disappears, making fertilizers that balance the pH more necessary. Small fauna (reptiles, insects, hares, birds, etc.) is greatly affected and practically disappears from the burned land. On the other hand, voles leave the burned farms and move, without any problem, to other farms, which can lead to the colonization of less affected areas.

Chemical measures

Anticoagulant poisons are frequently used to combat pests such as voles. The Junta of Castile and León has determined to grant permission and even distribute Chlorophacinone,[52] a diphenylindane derivative in various presentations (essentially, oleomiscible liquid, paste, granulated cereal, flavoured blocks, etc.).[note 6] Chlorophacinone is being evaluated by the European Commission to determine its definitive approval or prohibition,[53] although for the moment it is perfectly legal and is authorized in the Register of Phytosanitary Products of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.[54]

In Spain there are no studies that can indicate the active spectrum of Chlorophacinone, although there are field studies carried out with this same poison in the United States[55] by the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States. From them it is inferred that, being a first generation anticoagulant, the poison in question is more virulent in small mammals than in birds or cattle, although this depends on the degree of exposure. In addition, Chlorophacinone loses toxicity in contact with humidity. Nevertheless, it could be established that there is a real risk with all types of animals, not only rodents, being especially sensitive some birds such as bustards, larks, calandra larks, partridges and anatidae. Mammals, the most vulnerable have been found to be rabbits and hares (with a mortality rate of over 80%)[56] and among livestock, Chlorophacinone was shown to be very harmful to lambs, many of which died.[57]

In March 2007, when the pest had already spread widely throughout Tierra de Campos (Province of Palencia), the authorities of the Junta of Castile and León decided to dispense Chlorophacinone in the form of grains over 20,000 hectares of land. The poison was not properly prepared and massively affected pigeons, lagomorphs, alaudidae, wild boars and game or protected birds. Some environmental associations, including WWF/Adena, denounced the Junta for a crime against public health. Almost all the accusations were directed against the Territorial Service of Agriculture and Livestock of Palencia; shortly afterwards the complaints were joined by Global Nature Fund, the Coordinadora para la Defensa de la Cordillera Cantábrica and Ecologistas en Acción. The complaint was passed on to the Public Prosecutor's Office of the Court of Palencia, and the Nature Protection Service (SEPRONA) of the Civil Guard began to investigate with the help of the Department of Toxicology of the University of León. An attestation of SEPRONA informs about the provisional results of their investigations:

"We consider that these animals are a risk to public health and should in no case be consumed by the population until the massive use of this rodenticide ceases."

The aforementioned agricultural engineer, Fernando Franco Jubete, also opposed this decision supposedly taken by the authorities: "Chlorophacinone treatment should never have been approved, an ecological barbarity that solved nothing (...) a broad-spectrum chemical product cannot be thrown away in a generalized manner because it causes an ecological disaster".

Referring to this unfortunate matter, the secretary general of the Union de Pequeños Agricultores (UPA) of Palencia, Domiciano Pastor, explains that they had sent warnings to the Junta since September 2006, but the response of the authorities took too long. Regarding the accidental poisoning of other animals, he adds that "There were not so many deaths, but if the method is not good, we do not want it to be used".

End of the plague

During the winter, and at the beginning of 2008, the vole population in Castile and León returned to normal levels. The Junta of Castile and León, as explained by Silvia Clemente, Minister of Agriculture and Livestock, invested some 24 million euros to put an end to the plague.[58] As it was later demonstrated, despite the efforts of the administration, the poisons did not help to control the plague, but rather the vole population self-regulated, returning to normal. Much of this self-regulation was also due to climatological factors, as the mayor of Fresno el Viejo, one of the most affected localities, acknowledged.[59]

See also

Notes

- ^ See the case of the Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus).

- ^ One of the diseases that cause most social alarm is Tularemia.

- ^ Recommendations of the Junta of Castile and Leon before the opening of the hunting season (In Spanish)

- ^ Although there are no definitive reports, it is estimated that in 2007 the concentrations of country voles are between 1500 and 2000 individuals per hectare: verbal statements made to various media by both the German specialist Jacob Hensen and the Minister of Agriculture of the Junta of Castile and Leon, Silvia Clemente.

- ^ Cyclical plague of voles

- ^ Other legal (second generation) anticoagulants are Bromadiolone and Difenacoum, both coumarin derivatives, but Difenacoum is not indicated for voles but for mice. Moreover, a second generation anticoagulant is even more toxic than Chlorophacinone for birds or large mammals. Brodifacoum is also legal, but it is very harmful and difficult to handle, it is granted the highest toxicological classification, so it is only used in closed places, such as warehouses.

References

- ^ "La plaga de topillos comenzó en junio del año pasado". 20minutos.es (in Spanish).

- ^ a b Ruiz-Gordón, Luis M. (2–8 September 2007). "Cerco al enemigo público número uno". XL Semanal (in Spanish) (1036): 44–45.

- ^ "La plaga de topillos llega ya hasta la frontera con Portugal". tribuna.net (in Spanish).

- ^ "Los ecologistas responsables de la plaga de topillos". minutodigital.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 August 2007.

- ^ "El PSOE denuncia que los casos de tularemia de Castilla y León son de 270 y no los 42 que reconoce la Junta". terra.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "El PSOE asegura que la Junta "miente y oculta datos" sobre los afectados por tularemia". club-caza.com (archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Agricultura admite una densidad de 1.500 topillos por hectárea en Castilla y León". nortecastilla.es (in Spanish).

- ^ Luque-Larena et al. (2007)

- ^ a b González-Esteban & Jorge y Villate (2002, p. 385)

- ^ Henttonen (1987)

- ^ Marcström, Kenward & Engren (1988, p. 872)

- ^ Eadie & Nelson (1980, p. 103)

- ^ Arenaz Erburu (2001, p. 64)

- ^ Similar cases to those described in Eadie & Nelson (1980, p. 111)

- ^ "500 millones de topillos se devoran ahora el regadío". 20minutos.es (in Spanish).

- ^ "Los sindicatos congregan hoy a los agricultores para exigir a la Junta soluciones contra los topillos". nortecastilla.es (Archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ^ "Clamor ante los topiratones". nortecastilla.es (Archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ^ "Miles de manifestantes reclaman en Valladolid soluciones a la plaga de los topillos". nortecastilla.es (Archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ^ "Villalar está a la vanguardia en la lucha contra los topillos". pais.es (in Spanish).

- ^ a b "Quemas controladas en Valladolid para atajar la plaga de Topillos". 20minutos.es (in Spanish).

- ^ "Castilla y León inicia un plan para frenar la expansión de los topillos a más cultivos". abc.es (in Spanish).

- ^ "Los ganaderos, la otra cara de la moneda" (Archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ^ "La plaga de topillos pone en peligro la cosecha de uva en Castilla y León". adn.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Viticultores de Cigales recurren a las trampas con agua contra la plaga de topillos". nortecastilla.es (Archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ^ Ayarzagüena, Ibáñez & San Miguel (1976)

- ^ Delibes de Castro & Brunett-Lecomte (1989)

- ^ Palacios & Jubete (1988)

- ^ Delibes de Castro (1989, p. 18)

- ^ Arenaz Erburu (2001, pp. 64–65)

- ^ Blanco (1998, p. 241)

- ^ "B.O.C. y L. – N.º 61" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ^ Blanco (1998, p. 243)

- ^ Delibes de Castro (1989)

- ^ During the 1993 plague, it was documented in the province of Valladolid that an entire family of wolves fed mainly on voles. (Blanco (1998, p. 242) See also Delibes de Castro (1989, p. 20)

- ^ a b Delibes de Castro (1989, p. 20)

- ^ Margalef (1982)

- ^ Kowalski (1981, pp. 187–193)

- ^ Marcström, Kenward & Engren (1988)

- ^ Kowalski (1981, p. 188)

- ^ Krebs, Lambin & Wolff (2007)

- ^ Kowalski (1981, p. 187)

- ^ Eadie & Nelson (1980, p. 100)

- ^ Blanco (1998, p. 242)

- ^ Arenaz Erburu (2006, p. 20)

- ^ "Volverán a utilizar el veneno para combatir la plaga de topillos". 20minutos.es (in Spanish).

- ^ Boletín fitosanitario (2007, p. 18)

- ^ Arenaz Erburu (2006, pp. 37–42)

- ^ "I.N.R.A." Official I.N.R.A. website (in French).

- ^ "Real Decreto ley 11/2005 de 22 de julio" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2006.

- ^ "Unión de Campesinos Castilla y León" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2006.

- ^ "Artículo de Fernando Franco Jubete". Website of the Colegio Oficial de Ingenieros Agrónomos de Castilla y León y Cantabria (Official Association of Agronomists of Castile and León and Cantabria) (in Spanish).

- ^ "La Comisión Delegada para el Desarrollo Rural aprueba del Plan de Actuaciones contra la plaga del topillo" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ^ case nº 3691-35-8

- ^ Registration of Phytosanitary Products of the Ministry of Agriculture. (In Spanish)

- ^ Erickson & Urban (2004)

- ^ Chapuis (2001)

- ^ del Piero & Poppenga (2006)

- ^ "Los venenos no acabaron con los topillos". publico.es (in Spanish).

- ^ "La meteorología también ha hecho su trabajo» Archivado". nortecastilla.es (Archived in Wayback Machine) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 June 2008.

Bibliography

- Arenaz Erburu, Ángel María (2001). "El topillo campesino y el topillo de montaña". Daños en la agricultura causados por vertebrados (in Spanish). Ediciones Mundi-Prensa, Ministerio de agricultura, pesca y alimentación. pp. 61–66. ISBN 84-491-0490-4.

- Arenaz Erburu, Ángel María (2006). "El topillo campesino (Microtus arvalis)". Control de vertebrados perjudiciales en Agricultura (in Spanish). Madrid: Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de agricultura y ganadería. Madrid. pp. 74–79. ISBN 84-9718-407-6.

- Ayarzagüena, J.; Ibáñez, J. I.; San Miguel, A. (1976). "Notas sobre la distribución y ecología de Microtus cabrerae Thomas, 1906". Doñana, Acta Vertebrata (in Spanish) (3): 105–108.

- Blanco, Juan Carlos (1998). Mamíferos de España, segundo tomo (in Spanish). Editorial Planeta, S. A. pp. 239–243. ISBN 84-08-02827-8.

- Chapuis, J. L. (2001). "Eradication of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) by poisoning on three islands of the subantarctic Kerguelen Archipelago". Wildlife Research. 28 (3): 323–331. doi:10.1071/WR00042.

- Davis, S. A. et alter (2004). "On the economic benefit of predicting rodent outbreaks in agricultural systems". Crop Protection. 23 (4): 305–314. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2003.09.002.

- Delibes de Castro, Juan (1989). "Plagas de topillos en España". Revista Quercus. Observación, estudio y defensa de la Naturaleza (in Spanish). 35 (January 1989): 17–20. ISSN 0212-0054.

- Delibes de Castro, Manuel; Brunett-Lecomte, P. (1989). "Presencia del topillo campesino ibérico (Microtus arvalis asturianus, Miller 1980), en la meseta del Duero". Doñana, Acta Vertebrata (in Spanish). 7: 120–123.

- Dueñas Santero, Mª E.; Peris Álvarez, S. J. (1985). "Clave para los micromamíferos (insectívora y Rodentia) del Centro y Sur de la península ibérica". Claves para la identificación de la fauna española (in Spanish) (27). Department of Zoology. Faculty of Biology. University of Salamanca. ISBN 84-7481-331-X.

- Erickson, W.; Urban, D. (2004). Potential risks of nine rodenticies to birds and nontarget mammals: a comparative approach. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Washington D. C. USA.

- González Esteban, Jorge (1996). Estudio bionómico del topillo campesino Microtus arvalis asturianus Miller 1908, en la península ibérica (in Spanish). Tesis doctoral, facultad de Biología, Universidad de Barcelona.

- González-Esteban, Jorge; Jorge y Villate, Idoia (2002). "Microtus Arvalis (pallas, 1778), topillo campesino". In Palomo, L. J.; Gisbert, J. (eds.). Atlas de los Mamíferos terrestres de España (in Spanish). Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza. SECAM-SECEMU, Madrid. pp. 382–385. ISBN 84-8014-431-9.

- Henttonen, Heikki (November 1987). "The Impact of Spacing Behavior in Microtine Rodents on the Dynamics of Least Weasels Mustela nivalis: A Hypothesis". Oikos (3, Trophic Exploitation, Community Structure and Dynamics of Cyclic and Non-Cyclic Populations. Proceedings of a Symposium Held 25–27 May 1985, at Hallnas). 50 (3): 366–370. doi:10.2307/3565497. JSTOR 3565497.

- Kowalski, Kazimierz (1981). Mamíferos. Manual de teriología (in Spanish). H. Blume ediciones. ISBN 84-7214-229-9.

- Krebs, C.J; Lambin, X.; Wolff, J. O. (2007). Wolff, J.O.; Sherman, P.W. (eds.). "Social behavior and self-regulation in murid rodents". Rodent Societies: An Ecological and Evolutionary Perspective. 14. Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 173–181.

- Luque-Larena, Juan José; Baglione, Vittorio; Chiarati, Elisa; Vera, Rubén; Viñuela, Javier; Mateo, Rafael (2007). "Consideraciones científico-técnicas en relación a la campaña de control de la actual explosión demográfica de topillo campesino (Microtus arvalis) en zonas agrícolas de Castilla y León". Comunicado Conjunto de 13 de Febrero de 2007 (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- Marcström, V; Kenward, R. E; Engren, E. (October 1988). "El impacto de la predación sobre tetraónidas boreales durante los ciclos de ratones de campo: un estudio experimental". The Journal of Animal Ecology (in Spanish). 57 (3): 859–872.

- Margalef, Ramón (1982). "El sistema depredador / presa". Ecología (in Spanish). Barcelona: Ediciones Omega S. A.: 641–654. ISBN 84-282-0405-5.

- Palacios, F.; Jubete, F. et alter (1988). "Nuevos datos acerca de la distribución del topillo campesino (Microtus arvalis, Pallars, 1978), en la península ibérica". Doñana, Acta Vertebrata (in Spanish). 15: 169–171.

- del Piero, Fabio; Poppenga, Robert H. (2006). "Chlorophacinone exposure causing an epizootic of acute fatal hemorrhage in lambs". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 18 (5): 483–485. doi:10.1177/104063870601800512. PMID 17037620. S2CID 36741372.

- Eadie, Robert W.; Nelson, B. K. (1980). "Mamíferos que constituyen plagas". Control de Plantas y Animales. Problemas y Control de Plaga de Vertebrados. Natural Academy of Sciences (in Spanish). 5. Mexico: Editorial Limusa: 99–125. ISBN 968-18-0363-9.

- Roedores perjudiciales para los cultivos (in Spanish). Boletín Fitosanitario. Junta de Castilla y León. 2007.

External links

- Hunting Journal: Fire in Castile and Leon against the vole (In Spanish), by José Luis Garrido, 2007.

- The cyclical plague of voles (In Spanish), by Fernando Franco Jubete, 2007

- Biological control of vole plague Edited by GREFA, 2010.