1992 New Year's Day Storm

The New Year's Day Storm (Norwegian: Nyttårsorkanen), known in Scotland as the 'Hogmanay Hurricane', was an intense European windstorm that affected much of northern Scotland and western Norway on 1 January 1992. DNMI estimated the strongest sustained winds (10 min. average) and the strongest gusts to have reached 103 mph (166 km/h; 46 m/s) and 138 mph (222 km/h; 62 m/s), respectively.[1] Unofficial records of gusts in excess of 170 knots (87 m/s) were recorded in Shetland, while Statfjord-B in the North Sea recorded wind gusts in excess of 145 knots (75 m/s). There were very few fatalities, mainly due to the rather low population of the islands, the fact that the islanders are used to powerful winds, and because it struck in the morning on a public holiday when people were indoors. In Norway there was one fatality, in Frei, Møre og Romsdal county. There were also two fatalities on Unst in the Shetland Isles. Despite being referred to by some as a 'Hurricane', the storm was Extratropical in origin and is classified as an Extratropical Cyclone.

Meteorological synopsis

The New Year's Day Storm was classified as an Extratropical Cyclone, also known as a Mid-latitude cyclone, which are common in this part of the world, especially during the winter and autumn months.[2] In Europe, these are habitually referred to as European Windstorms.

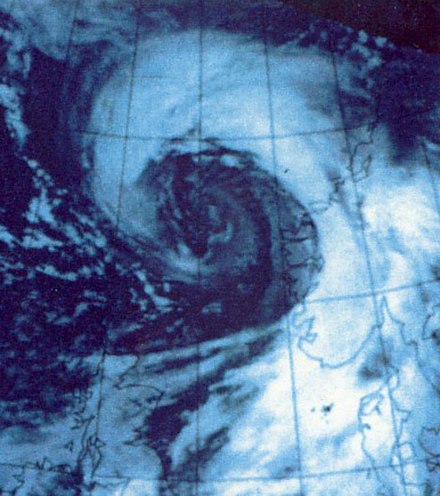

By 1200 UTC on 31 December 1991 an Atlantic low pressure centre of 985 mb had developed at the left exit of a strong WSW jet stream and was at 57°N 27°W. At this time a very sharp thermal trough (cold air) extended from south-west Iceland to the Hebrides with a thermal ridge building (warm air) behind it in the Atlantic.[3] A satellite image at 1600 UTC on 31 December showed a ‘clear eye’ in the cloud comma which indicates the dry air from the stratosphere descending into the developing low pressure as is a signature of explosive cyclogenesis. By 1800 UTC the low had deepened to 966mb.[3] At midnight (0000 UTC 1 January) the left exit of the jet stream was just behind the top of a sharp thermal ridge just west of Faroe, rapidly deepening the low centre to 957mb. Travelling at a speed of around 55 knots (63 mph; 102 km/h; 28 m/s), the low continued to deepen as it passed over Faroe and to the north of Shetland. Pressure falls were 5mb/hr across Shetland and 7mb/hr across Faroe.[3] The strongest winds arrived over the Shetland islands between 0100 UTC and dawn.[4]

The system is described as a 'Weather Bomb' due to its explosive cyclogenesis, exceeding the criteria of deepening by 24 mb in 24 hours greatly.[5] Explosive cyclogenesis usually occurs where dry air from the stratosphere flows down into a developing low pressure area and causes air within the depression to rise very quickly. This will increase its rotation, which in turn deepens the low pressure centre and creates a more vigorous storm.[3] The New Year's Day ‘Weather Bomb’ may have experienced double explosive cyclogenesis: firstly from the draw-down of cold dry air from the stratosphere and secondly the intercept of this already rapid development in the left exit of the jet stream with the warm air of a marked thermal ridge.[3]

| Formed | 30th December 1991 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 4 days |

| Dissipated | 3rd January 1992 |

| Highest winds |

|

| Highest gust | 197 mph (317 km/h; 88 m/s) |

| Beaufort scale | 12 |

| Lowest pressure | 947 mb (27.96 inHg) |

| Fatalities | 3 |

| Damage | Unknown. |

| Power outages | Unknown. |

| Areas affected | United Kingdom, Faroe Islands, Norway |

Part of 1991-1992 European Windstorm Season | |

Impact

Norway

The New Year's Day Storm was the most devastating windstorm in modern Norwegian history, in terms of material damage. 29,000 buildings were affected,[6] as well as large quantities of productive forest.[7] In Norway the total damage cost was estimated to more than 2 billion NOK (1992 values), adjusted for inflation equals nearly 4 billion NOK (2023 values) or $400 million USD . Norwegian mass media wrote afterwards that it was a once-in-300-years hurricane. Meteorologists suggested rather that it had a wind speed with a repeat period of about 50–200 years varying from region to region.[8] It had the highest wind speed measured in Norway until then, and has not repeated at least for the first 30 years after it. Despite the extremely strong winds, only 1 death was reported in Norway.

The maximum gusts recorded in Norway during the storm was 139 mph (224 km/h; 62 m/s),[8] which was recorded at 2 lighthouses; Svinøy and Skalmen in Møre og Romsdal county. Furthermore, the strongest 1-minute sustained winds in Norway of 117 mph (188 km/h; 52 m/s), also were registered at these 2 lighthouses which is equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Scale.[9][10][8] The Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET Norway) (Norwegian: Meteorologisk Institutt) estimated that the wind gusts rose as high as 135 mph (217 km/h; 60 m/s).[11] At Ålesund Airport in Vigra for example, wind gusts of 123 mph (198 km/h; 55 m/s) were recorded.[12] Reliable wind data for the West coast of Norway is difficult to source due to the remoteness of the region.

After the storm, a relief action called Aksjon Orkan was set up, based in Oslo, a city which was not affected by the windstorm. Reactions among the populace in the affected areas were mixed. The action was supported by the County Governor of Møre og Romsdal, but the mayor of Vanylven scorned the perceived intent to collect "food and clothes for the windstorm victims", stating the lack of need for such aid.[13] The people behind the action later claimed that this was never the purpose.[14] By the middle of January Aksjon Orkan had collected NOK 600–800,000.[14][15]

United Kingdom

This storm is regarded to be the most powerful storm to have hit the UK in reliable recorded history, and is a contender for the world's strongest extratropical cyclone in terms of raw windspeeds.[3]

In the UK, Scotland was worst affected. The wind was most severe in the Northern Isles, especially in Shetland. In Shetland, widespread structural damage was reported, and 2 people were killed - after their bird watching hut on Hermaness was destroyed during the violent gales.[16] The depression travelled towards the UK from off the coast of Canada on the 30–31 December 1991, travelling at 63 mph (101 km/h; 28 m/s).[3][4] The Met Office recognised the systems progression and subsequently issued warnings for parts of Scotland on the evening of the 31st December.[4] The strongest winds hit the Shetland Isles and Orkney Isles, beginning during the late evening hours of the 31st December 1991, with the strongest winds being from 01:00 to dawn on the 1st January 1992, local time.[4] The strongest winds were recorded at RAF Saxa Vord, located on Unst at the northern tip of the Shetland Islands, which recorded winds gusting to over 197 mph (317 km/h; 88 m/s)[4][3] however, as the station and recording instruments were destroyed, this has not been verified as an official record for the United Kingdom, and peak wind data is unobtainable.[4] Nevertheless, given damage and remoteness of the islands, it is expected that winds in some parts will have most certainly been higher at >200 mph (320 km/h; 89 m/s).[4]

| Location | Wind gust | 1-minute Sustained Winds | Elevation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAF Saxa Vord, Unst, UK | >200 mph (320 km/h; 89 m/s)[4] | Unknown | 285 m (935 ft)[17] | Equipment failure and severe damage to site[4] |

| Hermaness, Shetland, UK | >200 mph (320 km/h; 89 m/s)*[4] | >120 mph (190 km/h; 54 m/s)[4] | 18 m (59 ft)[18][19] | *Estimation derived due to damage and proximity to RAF Saxa Vord - location where 2 birdwatchers were hurled over a cliff.[16] |

| Muckle Flugga Lighthouse, Unst, UK | ~200 mph (320 km/h; 89 m/s)[3][19] | >120 mph (190 km/h; 54 m/s).[4][19] | 66 m (217 ft)[20] | 172 mph was the max. the station was able to record. Anemometer head snapped off. Sustained winds of >120 mph for more than half an hour.[3][4][19] |

| Sullom Voe Harbour, Shetland, UK | Unknown. | 150 mph (240 km/h; 67 m/s)[4] | 0 m (0 ft)[21] | A 'steady' 150 mph wind recorded by boats moored at Sullom Voe Harbour (Bft. 14).[4] |

| Statfjord-B, Shetland, UK | 194 mph (312 km/h; 87 m/s)[3] | 125 mph (201 km/h; 56 m/s)[16] | 0 m (0 ft) [22] | Report made just offshore by the UK-Norwegian shared oil platform. |

| Svinøy Lighthouse, Svinøy island, Norway | 139 mph (224 km/h; 62 m/s)[8] | 102 mph (164 km/h; 46 m/s)[8] | 35 m (115 ft)[23] | Joint highest sustained winds value in Norway.[9] |

| Skalmen Lighthouse, Smøla, Norway | 139 mph (224 km/h; 62 m/s)[8] | 102 mph (164 km/h; 46 m/s)[8] | 16 m (52 ft)[24] | Joint highest sustained wind value in Norway.[9] |

| Ålesund Airport, Vigra, Norway | 123 mph (198 km/h; 55 m/s)[12] | 76 mph (122 km/h; 34 m/s)[12] | 21 m (69 ft)[25] | Strongest winds occurred during the daylight hours.[12] |

| Halten Lighthouse, Frøya, Norway | 123 mph (198 km/h; 55 m/s)[8] | 89 mph (143 km/h; 40 m/s) | 70 m (230 ft)[26] | Extrapolated data above graph limit.[8] |

| Molde Airport, Årø, Norway | 121 mph (195 km/h; 54 m/s)[8] | Unknown. | 3 m (9.8 ft)[27] | Mean wind registration failed.[8] |

| Akraberg, Faroe Islands, Denmark | Unknown. | 92 mph (148 km/h; 41 m/s)[3] | 94 m (308 ft)[28] | Southern tip of Suðuroy (Danish: Suderø).[29] |

| Sumburgh, Shetland, UK | 113 mph (182 km/h; 51 m/s)[3] | 76 mph (122 km/h; 34 m/s)[3] [60-min mean] | 6 m (20 ft)[30] | Recorded at Sumburgh Airport.[3] |

| Butt of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, UK | 110 mph (180 km/h; 49 m/s)[31] | Unknown. | 37 m (121 ft)[32] | The highest wind gust recorded in the UK outside of the Northern Isles.[31] |

| Lerwick, Shetland, UK | 109 mph (175 km/h; 49 m/s)[3] | 72 mph (116 km/h; 32 m/s)[3] [60-min mean] | 82 m (269 ft)[33] | Home to over 20,000 people, Lerwick is the capital and largest town of the Shetland Islands.[34] |

| Sella Ness, Shetland, UK | >98 mph (158 km/h; 44 m/s)[3] | >72 mph (116 km/h; 32 m/s)[3] [60-min mean] | 10 m (33 ft)[35] | Inconsistent data reporting from this station, indicating potentially stronger winds.[3] |

| Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, Denmark | Unknown. | 69 mph (111 km/h; 31 m/s)[3] | 24 m (79 ft)[36] | Home to over 14,000 people (1992), Tórshavn is the capital and largest town of the Faroe Islands.[37] |

*It is important to recognise that due to the strength of winds, many stations failed at reporting values higher than they were programmed to, such as Muckle Flugga. This station was incapable of reporting a value above 150 kn (170 mph; 280 km/h; 77 m/s), therefore, it reached 150 kn and couldn't go any higher despite winds being stronger. Some stations too were destroyed at a certain threshold, and therefore did not provide data for what the peak winds are estimated to be.

The strongest sustained winds were reported at Sullom Voe Harbour on Shetland, with a steady 150 mph wind reported by ships sheltering in the harbour.[4] These winds are equivalent to those that are found in Category 4 hurricanes on the Saffir-Simpson Scale.[10] Likewise, the strongest gusts were experienced over the northern section of the Shetland Islands, with gusts of over 200 mph (320 km/h; 89 m/s) being reported.

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 60°45′N 0°53′W / 60.75°N 0.89°W / 60.75; -0.89 |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Shetland |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

Damages

Severe structural damage was reported across the Shetland Isles, with 2 tourists (aged 26 and 22) having been killed after their birdwatching hut was destroyed by gales of over 200 mph.[16] The remains of the tourists were found shoeless, one of them a short distance south along the path to the hut and the other more than half-a-mile to the east at the foot of an 18-metre cliff.[19] The RAF Saxa Vord station located at the northern tip of the Shetland islands also suffered from devastating damage, with all 3 radomes used by the British Armed Forces for NATO intelligence being completely destroyed for the second time, after being destroyed in 1960 by 170 mph wind gusts.[19] Nearby, a 30 m (98 ft) radio mast was snapped in half.[4] When questioned, Squadron leader Nicholas Gordon assured that national security had not suffered, but did not say if the surviving radars, designed to detect Soviet bombers and missiles, were still functional.[4] The Saxa Vord station suffered some of the most dramatic damage, with sections of the building seen with foundations swept clean of any construction.[19]

On Unst, the worst affect island by the storm, caravans and boats were reportedly 'flying through the air' and one caravan disappeared completely, presumably into the ocean.[4] Fish farms were badly hit, with £1.3 million (adjusted for inflation) worth of Salmon escaped from torn nets and smashed cages, surviving farms were offered record prices for their fish due to shortages.[4][38] Severe damage was reported to the 19th Century St. Magnus Bay Hotel in Hillswick, which was shifted on its foundations, and the next-door 'The Booth', Shetland's oldest pub,[4] took a battering, with the carpark being washed away - the combined repairs for these two buildings was expected to cost £1.3 million (adjusted for inflation).[4][38] Hagdale Lodge Hotel, which had capacity for 50 offshore oilrig workers, was nearly completely destroyed. The exterior walls of the lodge were collapsed in on themselves, and the site was deemed unusable, with new lodges arriving from Derbyshire and a complete rebranding off the site.[39] Two wings of the hotel had been 'disintegrated' and blew into the sea 0.5 miles (0.80 km) away, and the remaining had been punctured by flying wood and glass which embedded the standing walls.[19] In Sundraquoy, a woman narrowly escaped being crushed by a collapsing chimney which landed on her bed whilst she was away from home.[19]

A home on West Yell had its roof removed and blown 50 yards across the A968 before dropping back into the earth. In a caravan park in Lerwick, 22 caravans were destroyed, 8 of which had been "thrown through the air", seriously injuring 2 people, and an uninsured caravan was toppled after being struck by a neighbouring caravan.[19][4] The museum at Swedish Kirk, constructed as a memorial to Swedish fishermen had been ruined, with the building being launched 20 ft into the air.[19]

References

- ^ "Meteorologisk institutt". Meteorologisk institutt.

- ^ "Insurance impacts of European windstorms". stories.ecmwf.int. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Fraser, P. A. "Shetland's 'Weather Bomb': The Development of the 'New Year's Day Storm' of 01st January 1992". Academia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Carle, Gordon (10 July 2010). "A History of RAF Saxa Vord: The Storm – New Year 1991/92 Part 1". A History of RAF Saxa Vord. p. The Sunday Times 12 January 1992. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "What is a weather bomb?". Met Office. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Nyttårsorkanen". Aschehoug og Gyldendals Store norske leksikon. Kunnskapsforlaget. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- ^ Norwegian News Agency (29 January 1992). "Omfattende orkan-hærverk på skogen".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Aune, Bjørn; Harstveit, Knut (3 August 1992). "The storm of January 1. 1992" (PDF). Meteorologisk institutt.

- ^ a b c Gronas, Sigbjorn (October 1995). "The seclusion intensification of the New Year's day storm 1992". Tellus A. 47 (5): 733–746. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0870.1995.00116.x. ISSN 0280-6495.

- ^ a b "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Spensberger, Clemens; Schemm, Sebastian (23 April 2020). "Front–orography interactions during landfall of the 1992 New Year's Day Storm". Weather and Climate Dynamics. 1 (1): 175–189. Bibcode:2020WCD.....1..175S. doi:10.5194/wcd-1-175-2020. hdl:20.500.11850/411458. S2CID 218997732.

- ^ a b c d Ponce de Leon, Sonia (December 2013). "ERA Interim wind field for 1st January 1992 at 06UTC". Researchgate.net. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Kongsberg, Freddy; Tom-Egil Jensen (15 January 1992). "Hjelp! Vi er ikke i nød!". VG.

- ^ a b Olsen, Espen (16 January 1992). "Hemmelig jakt på fattige". VG.

- ^ "Orkanaksjon". Aftenposten Aften. 16 January 1992.

- ^ a b c d "The Hogmanay Hurricane - Shetland Dec 91/jan 92". Netweather Community Weather Forum. 26 August 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Saxa Vord from The Gazetteer for Scotland". www.scottish-places.info. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Hermaness Hike". Shetland.org. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fogg, Rob (3 January 1992). "Unhappy New Year as Homes are Blown Apart" (PDF). Shetland Times. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Muckle Flugga". Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Skinner, Simon. "Sullom Voe Port Information". Shetland Islands Council. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "The Statfjord area". www.equinor.com. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Svinøy Lighthouse", Wikipedia, 24 July 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Skalmen Lighthouse", Wikipedia, 3 July 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Ålesund Airport, Vigra", Wikipedia, 21 December 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Halten Lighthouse", Wikipedia, 7 March 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Molde Airport - Avinor". avinor.no. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Akraberg", Wikipedia, 7 March 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Suðuroy", Wikipedia, 1 January 2023, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Sumburgh Airport", Wikipedia, 1 January 2023, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ a b "MWR_1991_12 | Met Office UA". digital.nmla.metoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Butt of Lewis Lighthouse", Wikipedia, 7 March 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ "Lerwick topographic map, elevation, terrain". Topographic maps. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Orkney & Shetland". Alistair Carmichael. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "#GetOutside: do more in the British Outdoors". OS GetOutside. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Tórshavn topographic map, elevation, terrain". Topographic maps. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Tórshavn", Wikipedia, 24 December 2022, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ a b "£500,000 in 1992 → 2023 | UK Inflation Calculator". www.in2013dollars.com. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Carle, Gordon (8 September 2010). "A History of RAF Saxa Vord: The Baltasound Hotel and the Storm of 91/92". A History of RAF Saxa Vord. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

Books

- Bruaset, Oddgeir (1992), Orkanen (The Hurricane), Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget, ISBN 82-521-3909-4.